7

STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE

When I picked up this short novella looking for books the prisoners might enjoy, it seemed very different from the familiar tale of the upright Victorian gentleman and his evil doppelgänger that I thought I knew. Rereading it, I realized Jekyll and Hyde is actually a detective story, and its major character is neither Jekyll nor Hyde but the man who solves the mystery: Jekyll’s lawyer, a cordial fellow named Mr. Utterson. Jekyll appears only intermittently, and never speaks for himself until his written confession at the end of the book. Since Jekyll and Hyde is so short (it’s less than a hundred pages and can be read in a single sitting), it seemed odd that I hadn’t really engaged with it before. I must have been reading carelessly, breezing by on the assumptions I’d picked up from the movies.

Also, I’d assumed it was set in Edinburgh, where Robert Lewis Stevenson was born and raised, rather than in London (admittedly, the city is rarely named in the book). The London of Jekyll and Hyde is ugly, but it’s a secret, sinister kind of ugliness: the dirt of the city is shrouded by fog and lamplight. Much of the action takes place under “a pale moon” or during damp winter mornings or evenings, when “the fog still slept on the wing above the drowned city” and “the lamps glimmered like carbuncles.”

APRIL 22, 2014

I handed out copies of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to the men (another no-frills version costing just a dollar) and, taking it for granted they’d be familiar with at least the title, asked them for their impressions of the story from movies they’d seen or from popular culture. Most of them knew its outline from The Nutty Professor (the 1996 remake with Eddie Murphy), although I was surprised that Day-Day had heard of neither the book nor of the phrase “Jekyll and Hyde.”

The others were familiar with at least the split personality motif, and started talking about how their own personalities had changed when they were drunk or high.

“I used to get really friendly and give away all my stuff,” said Nick.

“I’d usually get into fights,” admitted Sig.

“I’d go the opposite way,” laughed Steven. “I’d get real affectionate.”

“Anyone ever turn into a completely different person?” I asked.

“I did,” said Turk. “But that was because I was on the run.”

“Same here,” said Nick, with his big goofy grin. “I was twenty-one and I’d just received a twenty-five-year sentence for murder. I stole a car and bought a U.S. Army uniform from a thrift store. I thought it would make people trust me. One night, I got pulled over by a cop after running a red light. I rolled down the window so he could see the stripes on my uniform. I said to him, ‘I’m real sorry about that officer, but I’m trying to get back to the base before curfew. If you write me up for a citation, I’ll be too late.’”

All the other men, I noticed, were listening closely. Even J.D.’s service dog, Falcon, had pricked up his ears.

“It worked. I couldn’t believe it,” continued Nick. “The cop goes, ‘All right, Sergeant, go ahead.’ I was in shock. You know, if he’d asked me anything—where was the base, what time was the curfew—I wouldn’t have known what to say. But he just let me go. I thought, ‘I can’t wait to tell my buddies about this.’ Then I remembered I was on the run. There was nobody to tell.”

NICK

Photo of Nick by Mark Hejnar.

It was a good story, but I never knew how much of what Nick said was true. Sometimes I wondered if he even knew himself. He told me many times that he was from Cambridgeshire, but he didn’t sound English and didn’t seem familiar with British geography. He’d also told me that his older brother was over seven feet tall (this part I believed: Nick himself was six foot seven) and had recently died of shame because people kept making fun of his height. Nick told me he was serving a life sentence for the accidental death of his best friend, Danny, after they’d both taken LSD. Nick said he ran straight into Danny, knocking him into a tree and killing him.

The newspaper and court records tell a different story. In their account, Danny, a seventeen-year-old high school senior, went missing on an April afternoon in 1982. Nick, then nineteen, was the last person to see him; in fact, Nick had driven to Atlantic City in Danny’s car (perhaps this was the kernel of his on-the-run story). Later, during the police investigation, Nick admitted to a friend who was wearing a wire that he’d killed Danny. Some of Danny’s belongings were found in Nick’s possession, and the police were convinced Nick was responsible for the murder. However, despite his taped confession, Nick couldn’t be convicted of murder without a body, so in June of that year he was jailed for robbery and auto theft. Eight years later, when Danny’s body was discovered buried in the woods, Nick received a murder conviction and a death sentence. He spent two years on death row before an appeals court voided his death sentence after considering mitigating evidence about his abusive upbringing.

Like most of the older guys at JCI, Nick had a couple of missing teeth. At first I assumed the men’s bad teeth were a result of their lifestyle: too many drugs and cigarettes, too much coffee. But my assumption was unconsidered, and I was thoughtlessly connecting bad teeth with bad habits. The answer was sadder and more straightforward. These men had lived for years with virtually no dental care, and instead of having their cavities filled, like those of us on the outside, they’d had the rotten teeth pulled out. For many years this was all the prison dentist was contracted to do. These men couldn’t even get their teeth cleaned. If a prisoner got punched in the mouth, or broke his teeth after tripping and falling while in leg irons, the damage wasn’t repaired. Recently, dental cleanings had been reintroduced, but the waiting list was very long: appointments with the hygienist were currently backed up for two years.

Despite his missing teeth and thinning hair, I could see that in his youth Nick must have been a handsome guy. Even now, at fifty-something, I could still see the shadow of his younger self. For some reason he always struck me as particularly clean, perhaps because his socks and sneakers looked especially white against his tanned skin. He told me he’d had two years of college before his arrest. When I first met him I found him likable and intelligent. After he’d been in the book club for a while, however, he began to annoy me. I started to find him loud, pushy, and a bit of a blowhard. I didn’t believe a lot of what he said, and it took a while for me to come to terms with his overbearing personality. Now I feel as though I understand him a little better than I did at first; I’m learning to admire his resilience and self-sufficiency.

I introduced the men to Robert Louis Stevenson; we talked a little about his life and the novel’s context, and then we began reading from the first chapter. Everyone read a section except Donald, who’d forgotten his reading glasses, and Charles, who was still having eye trouble. Although some of the men found Stevenson’s style a little wordy, they all agreed it was much easier to read than Shakespeare. I asked them to finish the first half of the novella before next week’s meeting.

I walked back toward the prison gate with Charles, who wanted to tell me about a recent experience he’d had.

“It actually has a Jekyll-and-Hyde-type twist,” he told me.

“Oh? What happened?”

“When Guy left,” he began, “I got a new cellmate, this black guy in his mid-thirties. He seemed decent, and even though I’d always prefer to be on my own, I felt OK about sharing a cell with him. Now, this guy has no money, no visitors, and no job except a sewing gig now and then that brings him in a few dollars he uses to get high. He’s got no possessions except an old analog television set that doesn’t work. I like the guy and I think he’s OK, so I look out for him. I share my coffee and snacks from the commissary. After six or seven weeks, this guy gets word from the court that he’s won his appeal. He’ll be heading back to Baltimore for a new trial. His lawyer doesn’t think the state’s attorney will want to retry him and they’ll probably either drop all charges or offer him a deal to plead guilty and receive time served. Either way, he’s looking to get out.”

We passed through two sets of doors and out into the compound.

“So last week I have an appointment with a glaucoma specialist,” Charles went on. “They take me downtown in chains and leg irons, and it’s another useless waste of time. I’m waiting around to see him the whole day, and when I finally get to see this guy, he takes one look at me and tells me I don’t have glaucoma. So they bring me back here. I’m standing outside my cell, waiting for the door to open, and this guy across the hall calls out to me, ‘Hey, your cell buddy checked into protective custody. The sergeant brought him down here and packed him up a couple hours ago. You better check your stuff.’

“My cell door opens and I go inside. I can tell immediately that some things are missing. I make a list. Later, I find out he owed around two hundred dollars for drugs and other stuff he bought on credit. The items he stole from me were small. Trimmers, a book light, a PlayStation memory card, a couple of PlayStation games. Those games aren’t cheap. He probably sold them or gave them to people he owed money to.”

I knew video games were popular among the prisoners, but I felt oddly disappointed to learn that Charles had a PlayStation. I didn’t know anything about them, and I assumed they were time-wasting toys for kids. Charles is close to seventy and a practicing Buddhist who meditates every day. I imagined him perhaps reading and writing in his spare time, not playing Grand Theft Auto or Ape Escape. Later, I learned that PlayStations can be used for all kinds of things: to watch movies, to listen to music, and to play games like chess and bridge that keep the memory quick and the brain sharp. I also remember it was Charles who’d set me straight about the cliché of prisoners having nothing but time on their hands. In prison, he’d told me, there’s a set time for everything: meals, commissary, showers, school, religious services, gym, yard time, free time. You can’t delay your meal for a few minutes, take an early shower, or postpone a task like you can on the outside. Everything you do is subject to detailed regulation. If you work, you might spend most of the day at your job, and when you’ve finished, had your dinner, and waited in line for a shower, it might be 6:00 or 7:00 p.m. You could get a couple of hours in the evening for writing letters and reading, although by then, he said, most people are too tired to do anything but watch television.

“Will you get your things back?” I asked.

“That’s the thing. He’d already sold them. See, this guy is smart. He knew the date of my eye appointment. He must have been planning this for a while. He’d already found buyers for my stuff, and they’d already paid him. On top of that, he’d been getting drugs on credit and he’d run up a huge debt. The guy I know across the tier told me I should write up an ARP.”

“What’s that?”

“Administrative remedy procedure. He said I should put him and his cell buddy down as witnesses. The sergeant was wrong for allowing this guy to check into protective custody and to pack his stuff while I wasn’t there. The next day the sergeant admitted it was his fault and said if we can’t get my stuff back, he’d take me to the confiscated property room and I could choose things of equal value.”

By now we’d reached the fence outside E and F blocks, where we went in different directions.

“Do you think you’ll find similar things in the property room?” I asked him.

“You know, I hate to say it,” he said, “but I may make out even better this way.”

“So what’s the problem?”

“I’m just real pissed at myself for letting my guard down. After all I’ve been through, I think I’m pretty skilled at assessing men’s characters. It really shook me up to find I’d miscalculated so badly. I thought this guy was Dr. Jekyll, but as soon as my back was turned, he changed into Mr. Hyde.”

APRIL 29, 2014

More bad news: Donald wasn’t in class. According to Turk, he’d been sent to Patuxent Institution, the nearby correctional mental health center, for a mandatory “risk assessment.”

“How long will that take?” I asked in dismay. Over the last year or so, I’d come to rely on Donald. He was one of the smartest men in the group, and he’d never missed a single meeting. He’d told me more than once that the book club had been instrumental in keeping him out of trouble. I believed him.

“Could be anything from sixty days to six months, depending on how many men they’re assessing,” said Turk stoically.

“Assessing for what?”

“Parole. Any time they’re thinking about giving a lifer a recommendation for parole, they want to see if you can pass the risk assessment. If you come out looking good, they send your parole papers to the governor’s desk.”

“You mean Donald could actually get paroled?”

A couple of the men laughed. Someone gave a loud snort of contempt.

“Put it this way,” said Turk. “They’ve been doing these risk assessments for the past fifteen years, and so far no lifer’s ever gotten parole.”

Charles explained. “It’s pointless. What going to Patuxent really means is two or three months of misery. Then you’re sent back over to wherever you were before.”

In just over a year, we’d lost Kevin, Guy, Sig for a while, and now Donald. It was true that other prisoners, equally bright and keen, had taken their places, but every time we lost one of the original nine men, even temporarily, it was a blow to the group’s integrity. I’d worked hard to win the men’s confidence, and continuity was vital. If it didn’t have a solid structure, the book club would seem weak, unreliable, and even unreal.

I was especially curious about how Turk would manage without Donald. Sometimes the pair was like a comedy duo. Donald was the low-key, laconic straight man; Turk was the rambunctious fall guy, roped in as the target of Donald’s provocations. They liked to tell me stories about life in C block, “the gated community” where the factory workers lived. Then I remembered that I’d once asked Turk about his “friend,” meaning Donald, and Turk had corrected me.

“I got no friends here,” he’d said. “Donald is my comrade. We go way back in time and we’ve been through a lot together.”

I realized this was exactly why the men didn’t let themselves grow too close. Make friends, and you’re setting yourself up for damage. Charles knew the score. Any day, you could wake up and find yourself alone.

Some people think this kind of close human feeling is exactly what’s missing in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Vladimir Nabokov, who lectured on Stevenson’s novel regularly at Cornell, felt there was “no throb in the throat of the story.” While he agreed that Jekyll’s plight is horrible, Nabokov argued that we don’t have the same sense in Jekyll and Hyde as we have in Kafka, for instance, of someone struggling to escape from the frame, to break out of the story into the world we inhabit, “to cast off the mask, to transcend the cloak or the carapace.”

We began, however, by talking not about Jekyll but about Hyde.

Sig was surprised by the appearance of the doctor’s alter ego. He’d expected someone much bigger. “I thought he’d look like a werewolf, or at least have fangs.”

“Me too,” said Vincent. “I imagined he’d be like the Incredible Hulk or something.”

“The book says he’s like a normal guy, except he’s smaller than Jekyll,” recalled J.D.

J.D. was right. Stevenson describes Hyde as “much smaller, slighter and younger” than Jekyll, who actually feels “lighter, happier in body” when he’s wearing the shape of Hyde. He may not be physically repulsive, but still, something about Hyde gives people the creeps. “There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why,” says Mr. Enfield, a relative of Mr. Utterson. “He gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point.”

“What about Dr. Jekyll? Does he look the way you imagined him?” I asked.

“Which Dr. Jekyll?” asked Steven.

“What do you mean? There’s only one.”

“There’s only one?”

“Sure. Henry Jekyll.”

“So who’s Harry Jekyll?”

“The same guy. Harry’s short for Henry.”

“Really? That’s crazy,” said Steven. “I thought he was, like, Dr. Jekyll’s dad or something.”

“No, it’s a nickname. It’s kind of old-fashioned, like calling someone Jack instead of John.”

“Wait, Jack’s short for John? That’s crazy,” repeated Steven.

“So now that we’ve straightened that out,” I said, “what did you make of Dr. Jekyll?”

“He seems older than I imagined,” said Nick. “In the movies he’s always this handsome young guy.”

In one part of the novel, Dr. Jekyll is described as “a large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty,” and in another place, he describes himself as “almost an elderly man.”

“Also, when he’s Hyde, he looks different on the outside, but he’s still Jekyll on the inside,” added Sig. “His thoughts don’t change. Everything is always from Jekyll’s point of view, even when he’s Hyde.”

“He writes letters and statements and even signs checks as Jekyll,” I agreed. “Hyde isn’t a separate personality living ‘inside’ Jekyll; he’s just a shape Jekyll sometimes takes on. In the last chapter he says that before he developed the potion, he’d already committed to a ‘profound duplicity’ of life.”

“What’s ‘duplicity’?” asked Turk.

“It means he’s been living a double life, right?” said Steven.

“Right,” I said. “Jekyll admits he’s always had certain inappropriate desires, and while he didn’t used to feel so conflicted about these feelings when he was young, when he started getting older and becoming well-known, they started to get inconvenient. Jekyll doesn’t create Hyde by accident, like in the movies. He creates Hyde deliberately, because he wants to do things that a man of his class, age, and position isn’t supposed to do.”

“I bet it’s something sexual. Going to prostitutes, maybe?” suggested Steven.

“No. I think it’s drugs. Didn’t they all use opium back then?” asked Nick.

“I think it’s violence. He kills that old guy and tramples on that little girl,” said Turk.

“Must be into S&M,” said J.D.

“Sadism, at any rate,” I said. “In the last chapter, ‘Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,’ he mentions, ‘lusting to inflict pain,’ and refers to ‘torture’ and ‘depravity.’”

“I think a lot of doctors get off on causing people pain,” said Turk.

“Maybe that’s why they become doctors,” suggested Vincent.

I talked to the men about the concept of sublimation—Freud’s idea of a negative impulse being transformed into something more beneficial. Freud came upon the idea, I told the men, after reading about a famous surgeon who, as a child, got pleasure from cutting off dogs’ tails.

“But Jekyll hasn’t been able to sublimate his sadistic impulses,” I reminded them. “It’s kind of ironic that he spends his days trying to stop people’s pain, and his evenings trying to cause it.”

“When you think about the ideas in this book,” said Sig, “‘good’ and ‘evil’ start to seem inadequate.”

“And whatever you can say about Jekyll, you can’t say he’s not self-aware,” I said. “He admits his inappropriate desires. In ‘Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,’ he says, ‘I was no more myself when I laid aside restraint and plunged in shame, than when I labored, in the eye of day, at the furtherance of knowledge or the relief of sorrow and suffering.’ In a way, he’s more honest than people who don’t tell anybody about their private lives.”

“Like guys on the down low,” mumbled Day-Day.

“Yeah. Or like all those sleazy politicians who get caught with prostitutes or doing crack or whatever,” said Nick.

“Right. If you’re in the public eye,” I said, “you’ve got to be really good at compartmentalizing your feelings. People sometimes use the phrase ‘a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality’ to refer to a person who has a completely different character from one moment to the next, but actually, Jekyll and Hyde aren’t that different. They both have the same mind. Only their bodies are different.”

We went on to talk about how, for Jekyll, compartmentalization never becomes second nature, which is exactly why he needs Hyde. Some people are experts at splitting off their sexual sides, for example, never thinking about sex during the day, when they’re at work, or when they’re sober; but Jekyll can’t relax into this kind of everyday hypocrisy—not because his conscience is too strong but because he’s too anxious about being discovered. He’s too proud to let go, too concerned about his reputation. Ironically—for a Victorian, anyway—he suffers from an inability to repress.

I thought about this as I drove back to Baltimore. To some degree, the more we’re able to repress, the more successful we are. An inability to compartmentalize is one of the main signs of mental illness. We discuss animal rights over ham sandwiches, rail against inequality but ignore the homeless guy asking for change, drive to environmentalist meetings in our SUVs. Especially in the corporate environment, we’re encouraged to keep our work lives separate from our private lives. We’re expected to be strategic rather than intimate in our revelations and relationships. We’re deterred from being too deeply self-revealing to our workplace colleagues, presenting a version of ourselves that’s neat and professional, that doesn’t spill over the edges, betraying emotional neediness, instability, or desire. If we can’t resist the urge to cry, curse, or pray, we lock ourselves in our offices—or, as a last resort, a bathroom stall—and let off steam in private.

I recalled Sergeant Kelly’s warnings.

“These men are convicts,” she’d informed us, standing at the front of the room with a set of handcuffs and a canister of teargas hanging from her belt. “They’re all liars, and they’re all manipulators. They’ll try to compromise you. You should never forget, these men are dangerous, hardened criminals. They’re not your friends.” Compartmentalization, I thought, is the soul of the prison, right down to its segregation cells.

Then I thought again. In the outside world, we sleep, play, and work in different places, with different people. In prison, you might very well live with the same people for twenty or thirty years, seeing them every day, at meals, in the shower, in the yard, in the visiting room, in the chapel, in the commissary. In that sense, prison life offers no compartmentalization at all.

Despite Sergeant Kelly’s warnings, I did consider the men in the book club to be my friends. Maybe they weren’t the kind of friends I could bring home for dinner, but that was only because they weren’t allowed to come. Had we met in other circumstances, we may not have been close, but then, I couldn’t imagine any other circumstances in which we’d have been brought together. Normally, I rarely venture outside my Baltimore neighborhood. Still, if what Sergeant Kelly said was true and the men did want something from me—even if only my sympathy or my allegiance—that didn’t necessarily make them different from anyone else. Everyone’s personality is socially adaptive, to some degree. We all make use of one another in all kinds of ways, none of which preclude genuine friendship or even love.

MAY 6, 2014

I kicked things off today by reciting Oscar Wilde’s famous line from his essay “The Truth of Masks”: “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth.” We talked about how Wilde’s line could be applied to Dr. Jekyll, and our conversation soon came around to the differences between what’s permitted today and what was acceptable in Victorian England in 1886. For the most part, the men had a very vague sense of history, and were under the impression that in Stevenson’s day, culture was far more repressive than it is today. In some ways this is true, but in other ways, things were—quite literally—far more open. London would have smelled horrible: from sewage dumped in the Thames, horse manure in the streets, and carcasses hanging in butchers’ shops, dripping blood onto the sawdust. There was no indoor plumbing, let alone hot water, deodorant, toothpaste, or shampoo. As a physician, Dr. Jekyll would have been familiar with birth, death, and disease, as well as overflowing chamber pots, infected abscesses, botched abortions, and other horrors, including venereal disease—the dark side of sexual freedom. It’s not surprising he has trouble keeping things separate.

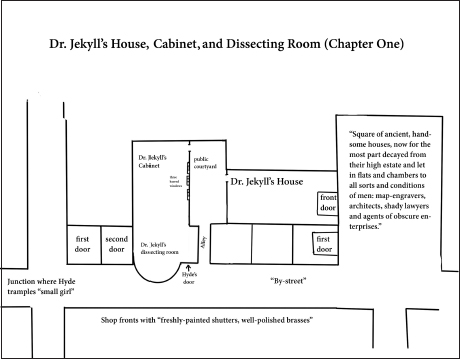

As we talked, I handed out copies of a diagram I’d made of Dr. Jekyll’s premises as Stevenson describes them (and this description is my favorite part of the book). The doctor’s house is the second from the corner in a square of “ancient, handsome” buildings. From the front, it has “a great air of wealth and comfort.” When you knock, the front door is opened by Poole, the butler, who escorts you into a “large, low-roofed, comfortable hall” paved with flagstones, warmed by an open fire, and “furnished with costly cabinets of oak.” Mr. Utterson calls this hall “the pleasantest room in London.”

To get to Dr. Jekyll’s laboratory, you have to go through the house—“a long journey down two pairs of stairs, through the back passage”—and outside, across an open yard that connects to a small alleyway. Here, facing the house is a stone building with a domed roof that the previous owner, a famous surgeon, had used as his “dissecting room.” This contains a small, old-fashioned operating theater, “once crowded with eager students and now lying gaunt and silent . . . the light falling dimly through the foggy cupola.” At the far end, a flight of stairs leads to a door covered with red baize. This is the door to Dr. Jekyll’s private office or “cabinet,” a large room with a fireplace, a chimney, a mirror, and three dusty windows barred with iron (even though they’re on the second floor) overlooking the courtyard. Another flight of stairs connects this room to a corridor that leads from the dissecting room to the back street door.

If you walk around the outside of Jekyll’s house, behind the handsome façade, you come to a side street at the rear. Walk down this street and you pass the alleyway leading to the courtyard, and “just at that point, a certain sinister block of building thrust forward its gable on the street. It was two stories high; showed no window, nothing but a door on the lower story.” This is the back door to the dissecting room—the door that provides the title of the book’s first chapter. It’s set in a recess and overhung by a gable; it has a “blind forehead of discoloured wall.” It’s “sinister,” “blistered,” and “distained.” It’s “equipped with neither bell nor knocker, and bears in every feature, the marks of prolonged and sordid negligence.” Tramps slouch in the recess and strike matches on the panels. Mr. Enfield has seen Hyde come and go through this entrance, and says, “Black-Mail House is what I call that place with the door.” He knows something strange is going on there, but tries to keep out of it.

“I make it a rule of mine,” he says. “The more it looks like Queer Street, the less I ask.”

“A very good rule too,” says the lawyer.

The essential point is that the buildings are connected. They’re both elements of Jekyll’s premises, necessary parts of the whole, just as his professional healing and his personal sadism are parts of the same personality—perhaps, as Vincent suggested, different manifestations of the same impulse. As Mr. Enfield puts it, “the buildings are so packed together about that court, that it’s hard to say where one ends and another begins.” In the same way, Jekyll and Hyde aren’t separate identities but one single personality in all its struggling, unruly complexity.

We’d talked at length about Jekyll’s dark side. Now I asked the men if they thought there were any good qualities in Hyde.

While we were discussing this question, Nick arrived late. The only seat left in the room, I realized, was a small, pink plastic chair that could almost have been designed for a nursery. As he sat down in it, Nick’s knees almost reached his chin. If the classroom chairs were too small for Sig, they were way too small for Nick, who was even taller. Could Nick and Sig, I wondered, be XYY males? Men born with an extra male chromosome are always taller than average males. It was once believed that XYY males had a propensity to psychopathy, but there was apparently no evidence to back up this theory. I wondered how Sig and Nick fit into their bunks. I wondered whether their cellmates were pissed to learn they had to share their space with someone who took up rather more than their fair share.

I realized I’d been staring at Nick.

“What do you think, Nick?” I asked him. “Any good qualities in Hyde?”

“Well, he pays off the parents of that little girl he crushes,” he said, referring to an incident in which Hyde tramples on a child, leaving her “screaming on the ground.”

“Yes, but only so they don’t go to the police.”

“It’s better than nothing,” countered Steven.

“And he didn’t have to give them a hundred pounds,” Nick added. “That was a lot of money in those days. I bet they’d have taken less.”

“Also, it’s Hyde’s choice to turn back into Jekyll. He takes the antidote. He doesn’t have to,” said Sig.

“He has high-class taste. I guess you could say that’s a good quality,” Steven pointed out. “Didn’t they say his house had really fancy napkins?”

I couldn’t remember the passage Steven was referring to, so we looked it up. It’s the moment when Utterson discovers that Hyde’s house, located in one of London’s most dismal slums, is, as Steven recalled, furnished with luxury and good taste. “A closet was filled with wine, the plate was of silver, the napery elegant,” we learn, “and the carpets were of many plies and agreeable in colour.”

“I think it was probably Jekyll that chose the carpet and all that,” Steven added.

I had to agree. I couldn’t imagine Mr. Hyde mulling over different shades of tableware.

MAY 12, 2014

By the following week, the Cut—the former Maryland House of Correction—had been completely demolished. The green Italianate cupola and weather vane that once stood on top of the roof now sat on the ground next to a huge pile of bricks and rubble. In between the layers of razor wire, a troop of yellow goslings waddled after their mother in the sunshine.

Inside the prison, the heat was stifling. To make things worse, a pipe had burst somewhere and the water had been cut off. There was nothing to drink, and the toilets wouldn’t flush. If the men needed to defecate, they had to either go outside in the yard or use a plastic bag. This had been going on since breakfast time, they told me. Today, the fetid reek of Victorian London didn’t seem so far away.

The Baltimore City Paper article had come out a few days earlier, and I thought the reporter, Baynard Woods, had done a terrific job. It was the cover story, and continued for eight pages; all in all, it was a well-researched, intelligent, and honest piece of reporting. For legal reasons, the photographer, J. M. Giordano, hadn’t been allowed to take pictures of the prisoners’ faces. This worked in his favor, as he’d had to find a creative way to photograph them. He’d taken black-and-white pictures of the men’s hands and arms—I recognized Steven, Sig, and Day-Day from their tattoos—holding their copies of Macbeth. Woods had also conducted an interview with Drew Leder, the philosophy professor who’d started the college program at JCI, and he’d included quotes from this interview as well as some of the dialogue from our class (including, of course, Day-Day’s expletives and references to gangs and “pussy”).

It’s always interesting to see people you know through different eyes, and I was slightly taken aback to find Donald referred to as “the old lifer in the hat.” I’d never thought of Donald, who’s fifty-three, as being old, nor had I noticed that Turk “stoops a bit as he walks.” Day-Day was described as “a young African-American man covered in tattoos, including one between his eyes,” and Nick as “an extremely tall white man with a goofy, almost innocent, grin.” As for myself, I was likened to the tough, elegant heroine of a Danish crime show. Other than this, the convicts came across just as they were: rough-and-ready but dedicated and eager to learn.

There was only one line that made me uncomfortable. “On the ride back to town through the rain,” wrote Woods, “Brottman said the prisoners were on their best behavior for my visit and that normally there was a lot more talk about ‘pussy.’” I knew at the time I’d expressed myself badly, and my statement on the page didn’t convey the good-humored reference to Day-Day I’d intended. Still, it was a single line hidden inconspicuously in the depths of an exceptionally upbeat and positive eight-page article that I imagined had to be great publicity for the prison and the college program.

The JCI librarian, Grace Schroeder, e-mailed me to say she’d made copies for the men in the reading group. I thought they’d be as thrilled as I was. Yet the first two prisoners I met that day, Charles and Vincent, both had the opposite reaction. In fact, Vincent was angrier than I’d even seen him before.

“I’ll never let a reporter here again,” he said bitterly.

“Why?” I was stunned. “What’s wrong with it?”

“Everything!” Vincent was red in the face. “It completely reinforces the public stereotype of prisoners. For five years I’ve been fighting with the prison administration to show the importance of these nonaccredited activities. The authorities think they’re a waste of time, and they’ll use this article to back up their argument. Instead of showing what we’ve achieved and writing about all the things we’ve learned, it just reinforces the image we’ve been battling against: that men in prison are covered with tattoos and they can’t have an intelligent conversation without using dirty words.”

“But most of the guys do have tattoos,” I objected. “And Day-Day did use those words.”

“Right,” said Vincent. “But they could have photographed the guys that don’t have tattoos. And why did he have to quote Day-Day? Why didn’t he quote Charles, or me, or Sig, or any of the other guys who had intelligent things to say? Everyone who reads this is going to think, ‘Typical: Give them a female instructor and all they can talk about is pussy.’ They’ll think we don’t know how to behave appropriately in a classroom setting. It’s like doing an interview on slavery in the 1800s and saying all blacks talk about is returning to the jungle.”

“Everyone I’ve spoken to about it has been so impressed,” I argued, feeling mortified by my own contribution to the scandal. “They can’t believe you guys are reading Conrad and Melville and Shakespeare. Ms. Schroeder liked it. Even the media relations guy from the Department of Corrections liked it, and his job is dealing with publicity.”

“Doesn’t matter,” insisted Vincent. “The only thing that matters to us is what the authorities in this prison think of it. They’ll find a way to use it against us, you wait and see.”

“The fact is, Day-Day shouldn’t have been using that kind of language,” Charles joined in. “If you’re at a family dinner, or at church, at a job interview, or in a place of education, you don’t talk that way.”

“But Day-Day’s never been in one of those situations. And anyway, we’re not in church or at a family dinner; we’re in a prison,” I said, highly conscious that both Charles and Vincent were politely refraining from mentioning the language I’d used.

“When I was at Patuxent,” continued Charles, “one man got drunk and didn’t come back from his work release. Long story short, we all lost our work release status because of him. One prisoner can screw everything up for the rest of us. If somebody in administration or custody finds out there’s a group in here led by a female where Day-Day’s kind of language is tolerated, they’d cancel it immediately. I know how custody thinks. Plus, it’s just ignorant. It’s not necessary to cuss in every sentence. Out of respect, I very rarely cuss when I’m talking to my wife, and during your classes I feel the same way about cussing in front of you.”

“It’s an eight-page article,” I insisted, starting to feel sick with guilt. “Eight pages of small print. Three thousand words, and it’s all incredibly positive except for that one single line.”

“Imagine a bucket of water,” said Charles, always ready with an analogy. “It could be the purest water from the purest mountain stream, but you add one tiny little drop of poison, and the whole rest of the water’s tainted, and anybody who drinks it will die.”

He was right. I’m sure Charles didn’t remember the lines, but Macbeth says something very similar in Act II, Scene II, lines 61–64, when he looks down at his hands after murdering the king:

Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.

My crime wasn’t of the same magnitude, but Charles and Vincent’s anger made me feel just as guilty as Macbeth. I desperately wanted to change the subject.

“How’s your eye, Charles?” I asked him.

“Real uncomfortable,” he grumbled. “My right eye works normally, but my left eye doesn’t, so everything looks blurry. If I could make some kind of eye patch or something to cover it, I’d be able to see, but I’ve got nothing to make one from.”

“That’s horrible,” I said as the other men began to arrive. A moment later Charles reached for his Styrofoam cup of water. His arm was shaking, and he accidentally knocked it over. Sig, who’d just arrived, went to get some paper towels to help clean up the spill. When he got back, I watched him mop up the water carefully. Then I saw him put an arm around the older man’s shoulder.

“How you doing, Chuck?” he asked. “Everything OK?”

It was the first time I’d seen one of the men show genuine kindness to another, and it made a deep impression on me.

The other men all wanted to know what I thought of the City Paper article. Now I was afraid and on my guard.

“What about you guys?” I said apprehensively. “Tell me what you thought of it.”

“I loved it,” said Steven. That was no surprise. But to my great relief, so did Sig, Nick, Turk, J.D., and Day-Day. They were thrilled to see photographs of their tattoos in the newspaper and asked me if I could bring in extra copies for them to give to their friends. In fact, after a long debate, even Vincent conceded that not everybody would see the piece the way he saw it.

“I suppose it could be enlightening for some people,” he confessed finally. “I sent a copy to my sister, and I’ve got to admit, she thought it was pretty cool.”