Rosemary is subject to attacks from spider mites, mealybugs, whiteflies, and thrips. Web (aerial) blight from Rhizoctonia solani produces twig and branch blight on the interior of the plant, so be sure to maintain good air circulation. A stem rot, caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, has been reported. A “stem knot” is quite common; the cause is unknown but it resembles bacterial infections caused by Pseudomonas, Agrobacterium, and Xanthomonas species, bacterial stem galls that are difficult to control because they are essentially systemic, growing from the inside out. This infection spreads through dirty pruning clippers and nearby plants, and newly propagated cuttings may carry it. Overhead watering and exceedingly damp and rainy summers are often associated with the arrival of rosemary stem gall. Organic mulches near the base of the plant often hold water and moisture near low-lying foliage, which provides a home and pathways for water-borne fungi and bacteria. Mulches of pea gravel or sand, which dry rapidly and radiate drying heat into the interior of dense rosemary plants, help to lessen diseases.

France, Spain, Portugal, the former Yugoslavia, and California supply most of the rosemary consumed in the United States, while Spain and France supply most of the rosemary oil.

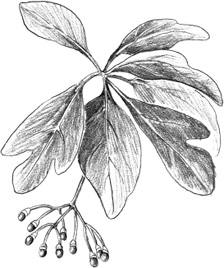

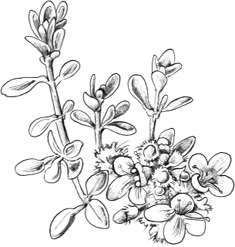

Rosemary has many varieties of growth pattern, floral color, and scent. Both upright and prostrate growth patterns are available. Floral color varies from intense blue-violet to lavender to pink to white. Scent varies from robust and piney to those with subtle, flowery, spicy undertones. While some cultivars are grown merely for their landscape value, all can be used in cooking and each imparts its own individual flavor. The distinguishing characteristics of some of the cultivars are listed here (infraspecific taxonomy is still uncertain because of a good, recent revision of the genus and is omitted).

Cultivar: ‘Albus’

Synonyms: ‘Albiflorus’, ‘White Flower’

Origin: This general name has been applied to a variety of different cultivars, ranging from pure white to pale blue and does not denote a specific clone (see, for example, ‘Huntington Blue’, ‘Logee White’, and ‘Nancy Howard’).

Cultivar: ‘Alderley’

Origin: France, by Alvilde Lees-Milne in 1960s; selected at Alderley Grange, Gloucestershire, England

Foliage/growth: small sprawling shrub with some pendant stems reaching to the ground and arching upward

Flowers: pale sky-blue

Synonyms: ‘Prostrate #4’

Origin: Cyrus Hyde, Port Murray, New Jersey

Foliage/growth: green, prostrate

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 29 percent alpha-pinene, 16 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Argenteus’

Foliage/growth: edged with white, upright

Flowers: blue-violet

Comments: noted as early as 1654, the silver-striped rosemary has apparently been lost to cultivation, but Silver Spires™ is another, recent mutation

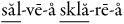

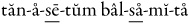

Cultivar: ‘Arp’

Origin: Arp, Texas; selected by Madalene Hill, Cleveland, Texas, in 1972

Hardiness: Zone 7

Foliage/growth: upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Essential oil: 42 percent 1,8-cineole, 19 percent camphor, 10 percent alpha-pinene (pine-camphor-eucalyptus)

Comments: very hardy

Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Arp’

Cultivar: ‘Athens Blue Spires’

Origin: University of Georgia, Athens, introduced by Allan Armitage, James Garner, and Jimmy Greer

Foliage/growth: upright

Flowers: light blue

Cultivar: ‘Aureus’

Synonyms: ‘Gilded’, var. foliis aureis

Foliage/growth: splashed with yellow, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Comments: variegation of the gilded rosemary, probably of viral origin, shows up only in certain climates and weather

Cultivar: ‘Benenden Blue’

Synonyms: var. angustifolius, var. angustissimus, ‘Collingwood Ingram’, ‘Ingrami’

Origin: 1930 Bonifacio, Corsica; selected by Collingwood Ingram, Benenden, Kent, England, and introduced into California by Elizabeth de Forest

Foliage/growth: narrow green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 51 percent alpha-pinene (pine)

Comments: initially erect branches soon arch and flow sideways

Cultivar: ‘Blue Boy’

Origin: Huntington Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Foliage/growth: narrow green, sprawling

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Comments: unique small leaves make it a beautiful plant for pots and bonsai

Cultivar: ‘Blue Lady’

Origin: ‘Prostratus’ × ‘Majorca’ by Sandy Mush Herb Nursery, Leicester, North Carolina

Foliage/growth: narrow green, flowing

Flowers: blue-violet

Origin: England

Foliage/growth: green, columnar

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 44 percent alpha-pinene, 30 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Bolham Blue’

Origin: found and selected by Mrs. Lena Hickson, Bolham, Devon

Foliage: glossy, yellow-green, lower surface pale gray-green

Flowers: calyx dark purple tinged green, corollas blue-purple, blotched with dark purple and a paler center

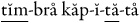

Cultivar: ‘Calabriensis’

Origin: England

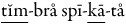

Cultivar: ‘Capercaillie’

Origin: Scotland

Foliage/growth: pale, vibrant green, bushy

Flowers: bright blue

Cultivar: ‘Capri’

Foliage/growth: prostrate

Cultivar: ‘Cascade’

Foliage/growth: prostrate

Cultivar: ‘Corsican Blue’

Synonyms: R. corsicus

Origin: originally from Corsica and introduced by Jackmans, Woking, Surrey, England

Foliage/growth: narrow, glossy dark green, upright

Flowers: lobelia blue

Cultivar: ‘Dancing Waters’

Origin: ‘Majorca’ × ‘Prostratus’ by Sandy Mush Herb Nursery, Leicester, North Carolina

Foliage/growth: dark green, sprawling

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Dark Logee Blue’

Origin: Country Greenhouses, Danielson, Connecticut

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Duplici’

Flowers: double blue

Comments: the double-flowered rosemary, listed by Parkinson in 1629, has been lost to cultivation

Cultivar: ‘Dutch Mill’

Origin: Barbara Remington, Forest Grove, Oregon

Hardiness: Zone 7?

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Essential oil: 32 percent alpha-pinene, 30 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Fota Blue’

Origin: Fota Island, Ireland

Foliage/growth: short, rather wide leaves, predominantly prostrate

Flowers: dark blue

Cultivar: ‘Gorizia’

Origin: Italy; introduced by Thomas DeBaggio, Arlington, Virginia

Foliage/growth: gray-green, upright

Flowers: lobelia blue

Essential oil: 21 percent bornyl acetate, 19 percent camphor, 15 percent borneol (camphor-rosemary)

Comments: good sturdy growth

Foliage/growth: upright

Flowers: blue

Cultivar: ‘Herbal Gem’

Foliage/growth: upright

Cultivar: ‘Herb Cottage’

Synonyms: ‘Foresteri’

Origin: Cathedral Herb Garden, Washington, D.C.

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Essential oil: 53 percent alpha-pinene, 21 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Holly Hyde’

Synonyms: ‘Yellow Green Leaf’

Origin: Cyrus Hyde, Port Murray, New Jersey

Foliage/growth: yellow-green, prostrate

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 28 percent 1,8-cineole, 17 percent camphor, 14 percent alpha-pinene (pine-camphor-eucalyptus)

Cultivar: ‘Howe’

Origin: Keith Howe, Country Gardens, Seattle, Washington

Hardiness: Zone 7?

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Huntington Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Alba’

Origin: Huntington Botanical Garden, San Marino, California

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: very pale blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Israeli Commercial’

Origin: Israel

Hardiness: Zone 8

Foliage/growth: large leaves

Flowers: very pale blue, infrequent

Comments: withstands shipping and storage better than most cultivars; stems produce aerial roots readily

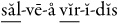

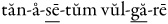

Cultivar: ‘Joyce DeBaggio’

Synonyms: ‘Golden Rain’

Origin: Thomas DeBaggio, Arlington, Virginia

Foliage/growth: edged in gold, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Essential oil: 19 percent camphor

Comments: good stable variegation; unique camphoraceous odor; similar to ‘Genges Gold’ from New Zealand

Rosmarinus officinalis

‘Joyce DeBaggio’

Cultivar: ‘Kent Taylor’

Origin: sport of ‘Majorca’, named after Kent Taylor of Taylor’s Herb Farm in Pasadena, California

Foliage/growth: green, prostrate

Flowers: dark blue

Comments: rare in cultivation

Foliage/growth: delicate, dark green, yellow-tinged young shoots

Flowers: pure white

Cultivar: ‘Light Logee Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Pale Blue’

Origin: Country Greenhouses, Danielson, Connecticut

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet in center, light blue violet on lower lips

Essential oil: 58 percent alpha-pinene, 19 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Lockwood de Forest’

Synonyms: sold under various aliases, such as ‘Prostratus’ or ‘Prostrate #5’

Origin: probably selfed selection of ‘Prostratus’ mid 1930s by Mrs. Lockwood de Forest, Santa Barbara, California

Foliage/growth: green, sprawling

Flowers: light blue-violet

Essential oil: 27 percent 1,8-cineole, 20 percent alpha-pinene, 15 percent camphor (camphor-pine-eucalyptus)

Comments: the plant usually sold as ‘Lockwood de Forest’ is ‘Prostratus’

Cultivar: ‘Logee White’

Synonyms: ‘Alba’

Origin: Logee’s, Danielson, Connecticut

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: white

Essential oil: 52 percent alpha-pinene, 19 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Lottie DeBaggio’

Origin: Thomas DeBaggio, Arlington, Virginia

Hardiness: Zone 8, marginal in Zone 7

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: very pale blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Madalene Hill’

Synonyms: ‘Hill Hardy’

Origin: introduced by Thomas DeBaggio, Arlington, Virginia

Hardiness: Zone 7

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Comments: very hardy

Cultivar: ‘Majorca’

Synonyms: ‘Collingwood Ingram’, ‘Rex #4’, ‘Wood’

Origin: Majorca

Foliage/growth: green, sprawling-upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 32 percent alpha-pinene, 11 percent camphor, 11 percent bornyl acetate, 10 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-rosemary-camphor-pine)

Comments: flowers of intense bluebird blue, the lower perianth segments with a deeper blotch

Cultivar: ‘Majorca Pink’

Synonyms: R. prostrata rosea, ‘Roseus’

Foliage/growth: pale green, sprawling

Flowers: amethyst-violet

Essential oil: 57 percent camphor

Comments: unique growth form and camphoraceous odor, but floral color more lavender than pink

Cultivar: ‘McConnell’s Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Mrs. McConnell’

Origin: Ireland

Hardiness: Zone 8

Foliage/growth: leaves short and rather wide; low growing, rather sprawling habit with erect laterals

Flowers: medium blue

Origin: Mercer Hubbard, Pittsboro, North Carolina

Hardiness: Zone 7?

Foliage/growth: green, sprawling

Flowers: blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Miss Jessopp’s Upright’

Synonyms: ‘Miss Jessup’s Upright’ (typographical error), ‘Miss Jessopp’s Variety’

Origin: Euphemia Jessopp via E. A. Bowles, England

Foliage/growth: green, columnar

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 53 percent alpha-pinene, 14 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Comments: ‘Corsicus’, ‘Fastigiatus’, and ‘Trusty’ are probably not sufficiently different to warrant separate names; ‘Miss Jessopp’s Upright’ has been applied to many different upright selections

Cultivar: ‘Mrs. Reed’s Dark Blue’

Origin: Joanna Reed, Malvern, Pennsylvania

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Comments: good intense floral color

Cultivar: ‘Mt. Vernon’

Origin: Mt. Vernon, Virginia

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Comments: no special reason to grow this other than its origin

Cultivar: ‘Nancy Howard’

Synonyms: ‘Alba Heavy Leaf’

Origin: Cyrus Hyde, Port Murray, New Jersey

Hardiness: marginal in Zone 7

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: white

Essential oil: 46 percent alpha-pinene, 23 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Comments: good semi-hardy white rosemary

Cultivar: ‘Pinkie’

Origin: Huntington Botanical Garden, San Marino, California

Foliage/growth: yellow-green, sprawling

Flowers: pink-lavender

Comments: probably closest to pink flowers in rosemary

Cultivar: ‘Portuguese Pink’

Origin: Portugal via Judy Kehs, Cricket Hill Herb Farm, Rowley, Massachusetts

Flowers: pink

Cultivar: ‘Portuguese Red’

Origin: Portugal via Judy Kehs, Cricket Hill Herb Farm, Rowley, Massachusetts

Flowers: dark pink

Cultivar: ‘Primley Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Frimley Blue’ (typographical error)

Origin: Paignton Zoo, Devon, England

Foliage/growth: narrow olive-green, upright

Flowers: China blue

Cultivar: ‘Prostratus’

Synonyms: ‘Dwarf Prostrate’, ‘Golden Prostrate’, ‘Huntington Carpet’, ‘Kenneth Prostrate’, ‘Prostrate #3’, ‘Santa Barbara’ (offered as separate clones, all these are seemingly identical)

Foliage/growth: green, prostrate

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 25 percent 1,8-cineole, 23 percent alpha-pinene, 13 percent camphor (camphor-pine-eucalyptus)

Comments: plant sometimes offered under this name is actually ‘Lockwood de Forest’, and ‘Prostratus’ is sometimes sold as ‘Lockwood de Forest’; ‘Prostratus’ has, unfortunately, been applied by nurserymen to any prostrate rosemary

Cultivar: ‘Pyramidalis’

Synonyms: ‘Robinson’s Variety’

Origin: W. Robinson, Gravetye Manor, England

Foliage/growth: narrow green, columnar

Comments: very similar to ‘Miss Jessopp’s Upright’ and possibly not sufficiently different to warrant a separate cultivar name

Cultivar: ‘Rampant Boule’

Origin: France

Foliage/growth: dense, ground-hugging

Cultivar: ‘Renzels’

Synonyms: Irene™

Origin: spontaneous seedling discovered in a California garden by Philip Johnson; named for Princess Irene (a.k.a. Renzels), Johnson’s black labrador

Foliage/growth: prostrate

Flowers: pale blue

Comments: U.S. PP124

Cultivar: ‘Rexford’

Origin: Rexford Talbot, Williamsburg, Virginia

Foliage/growth: upright

Flowers: blue

Cultivar: ‘Roman Vivace’

Synonyms: ‘Roman Vicace’ (typographical error)

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: wisteria blue

Essential oil: 27 percent camphor, 21 percent alpha-pinene, 14 percent camphene, 13 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine-camphor)

Cultivar: ‘Russian River’

Origin: Janis Teas, Teas Herbs and Orchids, Magnolia, Texas

Foliage/growth: upright

Cultivar: ‘Salem’

Origin: originally from Old Salem, North Carolina; introduced by Sandy Mush Herb Nursery, Leicester, North Carolina

Hardiness: marginal in Zone 7

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Sarah’s White’

Origin: Bernard Sparkes, Wye College, Kent, England

Flowers: white

Cultivar: ‘Severn Sea’

Synonyms: ‘Seven Seas’ (typographical error)

Origin: raised by Norman Hadden from a seedling, selected and obtained from Herbert Whitley, growing at Paignton Zoo, Devon, England, in the 1950s

Hardiness: marginal in Zone 8

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 36 percent 1,8-cineole, 26 percent alpha-pinene (pine-eucalyptus)

Comments: branches arch and dip when they reach 2 to 3 feet (61 to 91 cm)

Cultivar: ‘Shady Acres’

Origin: Theresa Mieseler, Shady Acres Herb Farm, Chaska, Minnesota

Foliage/growth: dark green, upright

Flowers: deep blue

Essential oil: 27 percent alpha-pinene, 23 percent 1,8-cineole, 7 percent verbenone (pine-eucalyptus)

Origin: South Wight Council, Ventnor Botanic Garden, England

Foliage/growth: green, prostrate

Flowers: blue

Comments: may not remain in cultivation

Cultivar: ‘Shimmering Stars’

Origin: ‘Prostratus’ × ‘Majorca Pink’ by Sandy Mush Herb Nursery, Leicester, North Carolina

Foliage/growth: broad green, sprawling

Flowers: pink buds opening to pale blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Sissinghurst Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Brevifolia’

Origin: chance seedling found in 1958 at Sissinghurst Castle, Cranbrook, Kent, England

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Sudbury Blue’

Foliage/growth: dense blue-green, upright

Flowers: speckled blue

Cultivar: ‘Talbot Blue’

Origin: Talbot Manor, Suffolk, England

Foliage/growth: upright

Flowers: blue

Cultivar: ‘Taylor’s Blue’

Synonyms: ‘False Tuscan Blue’

Origin: Taylor’s Herb Gardens, Vista, California

Foliage/growth: green, prostrate

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 31 percent 1,8-cineole, 28 percent alpha-pinene, 14 percent beta-thujone plus 1-octen-3-ol (sage-pine-eucalyptus)

Comments: unique sage-like odor

Cultivar: ‘Topsy’

Origin: Betty Rollins, Berkeley, California

Foliage/growth: green, sprawling

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Tuscan Blue’

Synonyms: ‘Erectus’

Origin: prior to 1948 from Tuscany, Italy, by W. Arnold-Forster, Cornwall, England

Foliage/growth: broad green, columnar

Flowers: dark blue-violet

Essential oil: 45 percent alpha-pinene, 15 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Very Oily’

Origin: Huntington Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Hardiness: Zone 7?

Foliage/growth: green, upright

Flowers: medium blue-violet

Essential oil: 39 percent alpha-pinene, 31 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Well Sweep’

Synonyms: ‘Alba Thin Leaf’

Origin: Cyrus Hyde, Port Murray, New Jersey

Foliage/growth: narrow green, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Cultivar: ‘Well Sweep Golden’

Synonyms: ‘Golden’

Origin: Cyrus Hyde, Port Murray, New Jersey

Foliage/growth: yellow-green, maturing to green, upright

Flowers: pale blue-violet

Essential oil: 46 percent alpha-pinene, 12 percent myrcene, 11 percent 1,8-cineole (eucalyptus-pine)

Cultivar: ‘Wolros’

Synonyms: Silver Spires™

Origin: discovered in 1986 by Christine Wolters, United Kingdom

Foliage/growth: pale green margined with white

Flowers: blue

Comments: Silver Spires™ is the trademark name at the U.K. Patent Office

Other cultivars merely mentioned in the literature with little qualifying characteristics are ‘Blue Gem’, ‘Blue Spears’, ‘Corsicus Prostratus’, ‘Heavenly Blue’, ‘Maggie’s Choice’, ‘Marshall Street’, ‘Robustifolius’, ‘Sawyer’s Selection’, ‘Tough Stuff ’, and ‘Wonderful’. The cultivars of rosemary have been selected from several botanical varieties and forms. Please remember that a cultivar is a category unto itself and is not subordinate to the botanical taxa. Many cultivars are also hybrids of botanical taxa and thus difficult to fit within any classification scheme. Thus, we may speak of ‘Nancy Howard’ as being selected from var. officinalis f. albiflorus but don’t bother to cite it as R. officinalis var. officinalis f. albiflorus ‘Nancy Howard’.

An evaluation of rosemary cultivars by Daniel Warnock and Charles Voigt at the University of Illinios found that five were especially good for use as Christmas topiaries: ‘Athens Blue Spires’, ‘Herb Cottage’, ‘Joyce DeBaggio’, ‘Shady Acres’, and ‘Taylor’s Blue’ (a sixth cultivar, listed as ‘Rex’, is a name that has been applied to more than one cultivar).

Rosemary leaves are GRAS at 380 to 4,098 ppm, while the oil is GRAS at 0.5 to 40 ppm. Rosemary leaves have antioxidant and antimutagenic properties from the content of phenolic diterpenes, particularly carnosic acid, carnosol, epirosmanol, and isorosmanol. These compounds show higher antioxidative activity than the commonly used BHA (butylated hydroxyanisole) and BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene) and have been commercially produced as natural food preservatives for fatty foods, such as potato chips. Luteolin is an antioxidant flavonoid in rosemary leaves.

Rosemary oil has also been demonstrated to be antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral. It stimulates the production of bile, prevents liver damage, and possesses anti-inflammatory and antimutagenic effects. Researchers have found that the volatile oil of rosemary leaves may be useful in treating diabetes and dementia; the extract has shown an anti-implantation effect in rats. Rosemary oil may also repel aphids and mites.

Aromatherapists who use rosemary oil should be aware that rosemary oil increases loco-motor activity, apparently from the content of 1,8-cineole. Aromatherapists should also be aware that rosemary oils vary considerably and there is not a standard rosemary oil, so the physiologic effects from one rosemary oil to another may vary. Rosemary oil has also been reported to induce contact dermatitis.

Important chemistry: The oil of commercial rosemary is predominantly composed of trace to 47 percent alpha-pinene, trace to 60 percent camphene, 4 to 60 percent 1,8-cineole, trace to 47 percent camphor, trace to 23 percent bornyl acetate, and trace to 18 percent borneol. Dried rosemary leaves have 2 to 4 percent carnosic acid and 0.2 to 0.4 percent carnosol. Cultivars vary in content of rosmarinic acid, but one of the highest is ‘Benenden Blue’.

R. officinalis L., Sp. pl. 23. 1753.

Native country: Rosemary is native to the Mediterranean region.

General habit: Rosemary is an erect or procumbent shrub to 2 m.

Leaves: Leaves are 15 to 40 × 1.2 to 3.5 mm, linear, leather-textured, with margins rolled back upon the lower side, bright green and wrinkled above, with a dense wool-like covering of white, matted, tangled hairs of medium length beneath, stalkless.

Flowers: Inflorescence and flower stalk have star-shaped, tangled hairs. Calyx is 3 to 4 mm, green or purplish and sparsely coated with matted, tangled hairs when young, later 5 to 7 mm, almost smooth, and distinctly veined. Flower is pale blue, pink, or white.

garden rue

Family: Rutaceae

Growth form: shrubby semi-evergreen perennial to 20 inches (50 cm)

Hardiness: Zone 6

Light: full sun

Water: moist but not wet; can withstand minor drought

Soil: well-drained garden loam, pH 5.5 to 8.2, average 6.7

Propagation: seeds in spring, 16,300 seeds per ounce (575/g)

Culinary use: limited; may be toxic to sensitive individuals

Craft use: none

Landscape use: avoid paths where bare legs can brush against it

French: rue odorante, péganion, rue fétide

German: Gartenraute, Raute, Weinkraut, Weinraute, Edelraute

Dutch: wijnruit

Italian: ruta

Spanish: ruda, armaga, arruda

Chinese: yün-hsiang-ts’ao

Arabic: sadab

Garden rue is appreciated for its wonderful blue-green leaves with an acrid, orange-like, poppyseed-like scent, but don’t touch those leaves on a hot, summer day or you’ll “rue the day.” Large, watery blisters will develop within the hour and, depending upon your sensitivity and the sunlight, will leave nasty scars. Scientifically, garden rue is called a “photosensitizer” because it requires sunlight to produce skin sensitization.

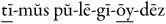

Garden rue is a semi-evergreen perennial shrublet widespread in sunny, arid areas of southern Europe and North Africa but perhaps native to the Balkans and the Crimea. This 20-inch (50 cm) high herb has slightly greenish yellow flowers in May to June and unusual sparse leaves coated with a blue wax.

Ruta graveolens

Ruta was the ancient Latin name for rue. The genus Ruta includes about seven species of Macronesia and the Mediterranean. Some authors have divided R. graveolens into R. hortensis Mill. and R. divaricata Tenore, but these species are not widely recognized. A variegated form (‘Variegata’) and a compact blue form (‘Blue Mound’) are sometimes available.

Southern Europeans, especially country folk, have a decided taste for rue leaves chopped in cheese and in salads. One of the lesser-known decorative and gustatory uses of rue is as a flavoring agent in grappa, once a home-brew moonshine of Italian peasants distilled from fermented grape skins left over after the wine pressing; grappa has taken on a more sophisticated image as a grape brandy in recent years. After the grappa is distilled, a rue stem is placed in a bottle and the grape brandy is poured over it; soon the blue-green rue stem is white. The bleached rue branches dances suggestively in the clear liquid with each movement of the bottle. This aqua vitae burns a path down your throat and leaves a slight, lingering, earthy taste of rue.

Solvent extracts of garden rue have been documented to have antifertility activity in rats when added to the diet up to ten days after coitus. The oil is documented to produce hemorrhage effects when taken internally, as well as stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, confusion, convulsions, and death; abortion may also result. The International Fragrance Association recommends that rue oil not be used for applications on areas of skin exposed to sunshine and to limit rue oil to 3.9 percent in a compounded fragrance. Steffen Arctander has advised, in his Perfume and Flavor Materials of Natural Origin, to avoid rue oil completely in fragrance and flavor work. Paradoxically, the essential oil of rue is considered GRAS at 1 to 10 ppm, and the Council of Europe has included garden rue oil in the list of flavoring substances temporarily admitted for use. On top of that, Japanese rsearchers have found that an extract of rue stimulates the growth of hair.

Rue is easily grown in well-drained garden loam in full sun. Its fertilizer and cultural requirements are minimal. In the spring, after the first year of growth, prune the stems of rue 6 to 8 inches above the ground. Follow this procedure each spring, and a well-shaped, handsome plant will result. Beware, though: rue can inhibit the growth of nearby plants, and Italian researchers have even isolated potential allelo-chemicals that could be used as pre-emergent herbicides.

Rue is a magnet for black swallowtail butterflies, which lay their eggs on the plant’s leaves; these hatch a colorful yellow, chartreuse, and black caterpillar that may defoliate the plant if the gardener is unaware. Garden rue has an unusual horticultural use as a breeding area for the tiny parasitic wasp Encarsia formosa, which serves as a natural control of whiteflies in the greenhouse; Doug Walker at the University of California-Davis noticed that garden rue plants were always infested with whiteflies in his greenhouse. He now uses the plants in his Integrated Pest Management program to propagate Encarsia and serve as an early warning monitor of whitefly invasion. Rue oil is toxic to some insects, such as Rhizopertha dominica and Tribolium castaneum, two pests of stored grain.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of garden rue is dominated by 2 to 84 percent 2-undecanone (methyl nonylketone), 5 to 39 percent 2-nonanone, 0 to 15 percent 2-undecyl acetate, and trace to 10 percent 2-nonyl acetate. The photosensitization is primarily produced by psoralen (0.126g/kg dry herb), bergapten (0.514 g/kg dry herb), and xanthotoxin (1.274 g/kg dry herb). Garden rue also contains a large number of quinoline and acridone alkaloids, such as rutaverine, arborinine, dictamnine, kokusagi-nine, skimmianine, fagarine, platydesminium, ribaliniu, and rutalinium.

R. graveolens L., Sp. pl. 383. 1753.

Native country: Rue is native to the Balkan Peninsula and the Crimea but widely naturalized from gardens throughout Europe and North America.

General habit: Rue is a smooth, blue-green semi-evergreen perennial 14 to 50 cm high.

Leaves: Lower leaves are more or less long-stalked, the uppermost almost stalkless; the ultimate segments 2 to 9 mm wide, lance-shaped to narrowly oblong to almost egg-shaped.

Flowers: Flowers are greenish yellow in a rather lax inflorescence.

Fruits/seeds: Fruits are smooth pockets with black seeds.

sage

Family: Lamiaceae (Labiatae)

Growth form: from tufted herbaceous perennials to shrubs many feet high

Hardiness: some hardy to Zone 6 but most cannot withstand frost

Light: full sun

Water: moist but not constantly wet; many can withstand minor drought

Soil: well-drained garden loam, pH 4.9 to 8.2, average 6.4 (S. officinalis)

Propagation: seeds or cuttings in spring, 3,400 seeds per ounce (119/g) (S. officinalis)

Culinary use: varied

Craft use: wreaths, potpourri

Landscape use: excellent in mixed borders

Salvia was a name used by the Romans for S. officinalis and was probably derived from salvus, a Latin word that denoted good health (sage was believed to have many healing properties). Fragrant foliage and brilliant flowers are typical of many of the 900 species of Salvia, so many of them make handsome additions to the herb garden and/or perennial border. Most species grow best when sited in full sun and well-drained soil, particularly those with gray foliage. Salvia is a genus with worldwide distribution but the greatest diversity is in the subtropics, especially the Americas, Sino-Himalayas, and southwestern Asia. Growth patterns range from herbaceous tufted alpines to woody shrubs.

Cleveland sage

Cleveland or blue sage was named by Harvard’s Asa Gray after the collector of the type specimen, Daniel Cleveland (1838–1929), but the commercial offerings of this species are actually hybrids, S. clevelandii × S. leucophylla Greene. In 1938 Carl Epling reported only one hybrid in existence, at the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden in California, and we suspect that this hybrid was later distributed in the trade simply as S. clevelandii. All the hybrids have pebbly gray foliage on stems to about 3 feet (1 m) high, and the foliage is scented of rose potpourri, a characteristic in common with S. leucophylla. While the flowers of the typical species are a good blue, backed by reddish calyces, they are lavender-blue in the hybrids. In both the species and hybrids, flowers are irregularly produced and do not present a dramatic show.

At least five selections of S. clevelandii × S. leucophylla are known, differing only slightly in scent, growth pattern, and/or floral color: ‘Allen Chickering’, ‘Aromas’, ‘Compact Form’, ‘Santa Cruz Dark’, and ‘Whirley Blue’. Even the unnamed clone passed around in the herb trade as simply S. clevelandii is from this cross. As might be expected of their southern California origins, Cleveland sage and its hybrids want well-drained, gravelly soil in full sun, probably hardy only to Zone 9. While some books have advocated that Cleveland sage be used in cooking, it does not have GRAS status.

‘Winifred Gilman’ seems to be the only cultivar in the trade that may be pure S. clevelandii. ‘Winifred Gilman’ is more difficult to grow than the hybrids and is characterized by pebbly green foliage scented of eucalyptus. Flowers should be dark violet-blue, but it has never flowered for us.

Important chemistry: The foliage of the hybrids is scented of rose potpourri with about 44 percent camphor and 19 percent 1,8-cineole in the essential oil; a multivariate analysis of the essential oil components confirmed no statistical differences among the named cultivars. The essential oil of ‘Winifred Gilman’ is characterized by around 20 percent 1,8-cineole with a eucalyptus-like scent.

peach sage

Peach sage, also known as fruit sage, was named by Paul Standley, who documented the trees and shrubs of Mexico and Central America in the early twentieth century. The name honors Doris Zemurray Stone (1909–1994), a friend of the Escuela Agricola Panamericana, not some ancient goddess named Doris (as apocryphally repeated in most horticultural books on sage). Doris Zemurray Stone was the daughter of Sam Zemurray (Schmuel Zmurri), founder of the United Fruit Company; she was an archaeologist and ethnographer and served as director of the National Museum of Costa Rica.

Salvia dorisiana

The leaves of peach sage can be dried and used in potpourri but have also been used to complement peach dishes, such as cobbler, despite its lack of GRAS status.

Peach sage is a robust, open plant with large leaves, 21 to 50 inches (7 to 14 cm) long by 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 cm) wide, pale green, fleshy, and bristly-pebbly. Peach sage prefers part shade and constantly moist soil. This sage is extremely sensitive to frost, and since the rose-red flowers start forming very late in fall, it is often cut down before peak flowering. Under good conditions, peach sage may reach 47 inches (1.2 m) high.

Important chemistry: The essential oil is dominated by 27 to 28 percent perillyl acetate, 17 to 21 percent methyl perillate, and around 10 percent beta-caryophyllene, providing a peach-like odor reminiscent of perilla.

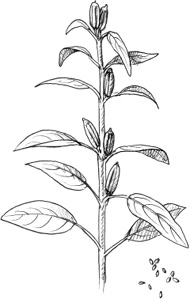

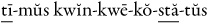

pineapple sage

Salvia elegans (“elegant sage”) is a vigorous, strong-stemmed plant with red-tinged green leaves that are scented of pineapples, giving it its common name. Salvia rutilans, a name sometimes applied to pineapple sage, is known only from cultivation, differing only in the smaller calyces and downier stems and probably not specifically different from S. elegans. Contrary to some popular horticultural books, pineapple sage is not a variety of S. splendens F. Sellow ex Roem. & Schult., the scarlet sage. ‘Honeydew Melon’ is a selection with a melon-like scent; ‘Golden Delicious’ has golden leaves, and ‘Frida Dixon’ is somewhat dwarf.

The young shoots of pineapple sage have been used to flavor cold drinks, and its fresh leaves and flowers have been used as garnishes for desserts despite its lack of GRAS status. Leaves are egg-shaped, tapering to a tip, 1 to 4 inches (2.5 to 10 cm) long arising from dark red, downy stems. The pineapple sage, like the peach sage, produces brilliant scarlet flowers just about the time it is cut down by frosts. Pineapple sage may reach 47 inches (1.2 m) high under optimum conditions.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of pineapple sage leaves contains 27 percent beta-caryophyllene, 22 percent 2-propanol, and 10 percent (E)-beta-ocimene.

Salvia elegans

Greek sage

Greek sage often comprises up to 95 percent of the dried, imported sage sold in the United States. Its eucalyptus-like aroma lacks the understated sweetness of garden sage, and the heavy presence of Greek sage may account for the musty odor of the commercial dried product. Often referred to as S. triloba in older literature, Greek sage has historical uses similar to garden sage. Greek sage is illustrated with what may be Rosa pulverulenta on the “blue bird fresco” in the House of Frescoes at Knossos (c. 1450 B.C.E.). The elongated egg-shaped leaves have two smaller lobes near the base. All vegetative parts are covered with a dense wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length. Bright blue flowers appear in early winter.

Greek sage is extremely variable in both morphology and oil. Greek sage usually has a higher oil yield than garden sage. The oil is antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and antiviral.

While Greek sage is only reliably hardy in Zone 8b, hybridization with S. officinalis offers potential for new morphological and chemical types hardy further north. ‘Newe ‘Ya’ar’, a hybrid (primarily S. officinalis × S. fruticosa) cultivated in Israel, withstands heat very well, occasionally appears on the U.S. market, and is easily rooted; unfortunately, it is not routinely hardy above Zone 8.

Important chemistry: The oil of S. fruticosa consists of 19 to 68 percent 1,8-cineole, trace to 45 percent camphor, trace to 38 percent viridiflorol, 3 to 27 percent alpha-pinene, 2 to 11 percent beta-pinene, and trace to 10 percent beta-caryophyllene.

Spanish sage

The nine subspecies of Salvia lavandulifolia, the lavender-leaved sage, vary greatly in morphology and essential oils. In the cultivated plants in North America, the simple, stalked leaves are narrowly parallel-sided and covered with a dense wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs. The blue flowers are rarely produced.

The essential oil is considered GRAS at 2 to 50 ppm but finds very little use in flavor work; it is primarily used to scent soaps. Ingestion of Spanish sage oil brings on convulsions from the toxicity of the camphor content. The dose at which rats show symptoms of toxicity is 0.005 ounce oil per pound of body weight (0.3 g/kg), while above 0.008 ounce per pound (0.5 g/kg) convulsions occur; above 0.05 ounces per pound (3.2 g/kg), the dose is lethal. Translating this to a 150-pound human, these numbers would be 0.72 ounce, 1.2 ounces, and 7.7 ounces, respectively.

The sabinyl acetate in the essential oil induces birth defects in mice, a cautionary indication that this oil should not be used in aromatherapy by pregnant women. Research has shown that an extract of S. lavandulifolia significantly decreases the blood-sugar levels of diabetic rats; it also displays anticholinesterase activity. Spanish sage oil has been found to enhance the memory in healthy young volunteers and may have usefulness in dementia therapy, particularly Alzheimer’s disease.

Important chemistry: The essential oil has 6 to 59 percent 1,8-cineole, 1 to 39 percent camphor, 2 to 28 percent beta-pinene, 3 to 28 percent alpha-pinene plus tricyclene, trace to 16 percent myrcene, trace to 14 percent camphene, 2 to 12 percent limonene, trace to 23 percent borneol, and trace to 12 percent viridiflorol, plus alpha-terpineol plus alpha-terpinyl acetate.

garden sage

French: sauge

German: Salbei

Dutch: salie

Italian: salvia

Spanish: salvia

Portuguese: salva

Swedish: salvia

Russian: shalfey

Chinese: chjing-chieh

Japanese:

Arabic: mariyamiya

The specific epithet, officinalis, refers to the medicinal value of the sage in years past. Imported sage is chiefly gathered from the wild along the Dalmatian coast of the former Yugoslavia and Albania, hence an alternative name is Dalmatian sage. As a wild-gathered herb, it actually consists of not only S. officinalis but also S. fruticosa and hybrids of the two species. In fact, only 5 to 50 percent of imported sage may be S. officinalis.

Garden sage is widely used in flavoring condiments, cured meats (particularly sausage and poultry stuffing), liqueurs, and bitters. Garden sage oil is used to impart herbaceous notes to fragrances. The leaf is GRAS at 300 to 4,777 ppm; the oleoresin is GRAS at 10 to 139 ppm, while the essential oil is GRAS at 2 to 126 ppm. Sage yields an effective antioxidant that is relatively odorless and tasteless; this has been proposed as a preservative for fatty foods such as potato chips. The essential oil of sage is anti-mutagenic. Sage extract has also been found to be effective in the management of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sage kills both bacteria and fungi. Sage extract may be useful in the control of Varroa mites in bee colonies.

Depending upon the source, garden sage seed may germinate unevenly and produce very variable plants, few of which have heavy, thick leaves with robust growth and the desired odor. Named cultivars are easily propagated from hormone-treated cuttings about 1½ to 2 inches (4 to 5 cm) long. If taken in late fall to early winter, the cuttings will establish ample roots in the greenhouse for transplanting by spring. Cuttings should be taken from new growth of non-flowering stems, preferably from the base of the plant if available.

Transplants should be set 15 to 24 inches (39 to 61 cm) apart in rows set about 3½ feet (about 1 m) apart. Approximately 7,000 plants per acre (17,297 plants/ha) would be required with these spacings.

Salvia officinalis

The home gardener will usually be satisfied with one or two large plants of sage. Home gardeners should pinch the growing tips regularly throughout the first summer to create many branches; also cut the plant back about a third before new growth starts in the second year. Before planting, a high grade commercial fertilizer (depending on the results of the soil test), with 89 to 134 pounds per acre (100 to 150 kg/ha) of nitrogen, should be drilled into the rows. A side-dressing of fertilizer should be given six to eight weeks later. After plants are established, fertilize about the time that growth starts in spring and repeat about the first week in June. Cultivate lightly through the spring and summer to control weeds. The first year should have one harvest of the terminal 3 to 5 inches (8 to 13 cm) during the fall; afterward, harvesting can be two to three times per summer.

Leaves and small tops will bring the best prices; keep the percentage of stems below 12 percent. In the first year, the yield is usually small, ranging from 200 to 600 pounds dried leaves per acre (224 to 672 kg/ha). In the second and subsequent years 1,500 to 2,000 pounds per acre (1,681 to 2,241 kg/ha) may be obtained. A regimen of three successive harvests produces the highest biomass yield. Experimental plantings in New Zealand have produced the phenomenal yield of 1,106 to 2,432 pounds per acre (1,240 to 5,080 kg/ha) the first year.

Sage loses its color and flavor rapidly with age, so bale and market the product as soon as possible. Blooming significantly reduces the harvest, so choose a cultivar with low flowering potential.

Sudden phytophthora, verticillium, and fusarium wilts are the most obnoxious diseases to confront sage. These can usually be remedied by increasing the drainage of the soil. Powdery mildew (Oidium spp.) occurs sometimes in hot, humid weather. Nematodes will also attack sage, and their presence accelerates sudden wilts.

Garden sage has a few cultivars, selected mainly for foliar or floral colors. All may be used for cooking, imparting their own particular flavors, but some taste better than others.

Cultivar: ‘Albiflora’

Foliage/growth: broad leaves, low height

Flowers: white

Essential oil: 37 percent beta-thuone and 23 percent camphor

Comments: tends to be weak and prone to wilts in hot climates

Cultivar: ‘Aurea’

Foliage/growth: gold-flushed leaves, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue

Comments: vastly confused in the horticultural literature with ‘Icterina’ (which see); ‘Aurea’ is a uniform golden green and very weak plant, not worth growing except as a curiosity

Cultivar: ‘Berggarten’ (“mountain garden”)

Synonyms: ‘Herrenhausen’

Origin: Herrenhausen Grosser Garten, Hanover, Germany

Foliage/growth: broad leaves, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue, infrequent

Essential oil: 25 percent camphor and 10 percent camphene

Comments: the best agronomic plant of the available cultivars, with very large leaves, few flowers, and an oil that matches much of the imported Dalmatian sage

Foliage/growth: narrow, upright, medium height

Flowers: lavender-blue

Essential oil: 21 percent 1,8-cineole and 19 percent camphor

Cultivar: ‘Crispa’

Foliage/growth: variegated with wavy margins

Cultivar: ‘Grandiflora’

Foliage/growth: leaves larger and wider with a heart-shaped base

Flowers: larger than typical

Cultivar: ‘Grete Stolze’

Foliage/growth: pointed, pale gray

Flowers: mauve-blue

Cultivar: ‘Icterina’

Synonyms: ‘Aurea’ (incorrect name, see earlier)

Foliage/growth: edged in gold, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue

Essential oil: 22 percent camphor, 11 percent alpha-thujone, and 10 percent alpha-humulene

Comments: generally not hardy above Zone 8

Cultivar: ‘Kew Gold’

Origin: a sport of ‘Icterina’, to which it sometimes reverts, selected by Brian Halliwell, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, England

Foliage/growth: gold on green

Comments: seems to be a more vigorous version of ‘Aurea’

Cultivar: ‘Milleri’

Foliage/growth: red, blotched (maculae)

Cultivar: ‘Purpurascens’

Synonyms: ‘Purpurea’

Foliage/growth: broad, purple leaves, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue

Essential oil: 17 percent alpha-thujone, 17 percent alpha-humulene, 15 percent camphor, and 13 percent beta-pinene

Comments: oil matches much of the imported Dalmatian sage; good garden accent; a selection of this is ‘Robin Hill’

Cultivar: ‘Purpurascens Variegata’

Foliage/growth: cream markings on some leaves

Comments: a sport of ‘Purpurascens’

Cultivar: ‘Rubriflora’

Foliage/growth: narrow, upright, somewhat sparse

Flowers: pink

Essential oil: 27 percent alpha-thujone and 19 percent camphor

Comments: oil matches much of the imported Dalmatian sage

Cultivar: ‘Salicifolia’

Foliage/growth: leaves very long and narrow

Cultivar: ‘Sturnina’

Foliage/growth: white-green

Cultivar: ‘Tricolor’

Synonyms: Parkinson’s “party-colored sage”

Origin: probably a variegated ‘Purpurascens’

Foliage/growth: purple edged in white, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue

Essential oil: 20 percent camphor, 19 percent alpha-humulene, 14 percent alpha-thujone, and 12 percent beta-pinene

Comments: not hardy above Zone 8 and rather weak in growth but a good garden accent

Synonyms: ‘Woodcote’

Foliage/growth: broad leaves, low height

Flowers: lavender-blue, infrequent

Essential oil: 17 percent camphor and 11 percent alpha-thujone

Comments: good culinary sage and garden plant; occasionally offered in a variegated form

‘Holt’s Mammoth’ is another cultivar that needs clarification. What is the real ‘Holt’s Mammoth’? The original clone reputedly had larger leaves than the type; the cultivar usually offered in the United States is often propagated from seeds and no different from the type or any other seed-propagated sage. Is the sage now known as ‘Woodcote Farm’ the real ‘Holt’s Mammoth’? No original good description exists of ‘Holt’s Mammoth’, so we are at a loss to clarify this problem. ‘Woodcote Farm’ is the most frequently offered sage cultivar for fresh leaves at vegetable counters in the United States. In Great Britain, besides ‘Woodcote Farm’, some other commercial cultivars include ‘ Archers Long Leaf’, ‘Archers Broad Leaf’, ‘Andrews’, ‘Extracta’, ‘Preen 38’, and ‘Wisley’. Additional cultivars with few published descriptions include ‘Emanuel’, ‘Jefferson’, and ‘Wurzburg’.

Important chemistry: The essential oil and dried sage from the Dalmatian coast of the former Yugoslavia and Albania show tremendous variability in the principal components: trace to 47 percent alpha-thujone, 1 to 36 percent beta-thujone, 3 to 38 percent camphor, 4 to 25 percent 1,8-cineole, and trace to 16 percent borneol. Populations from Serbia and Montenegro have 8 to 25 percent alpha-thujone, trace to 25 percent camphor, and 6 to 13 percent 1,8-cineole. An examination of the essential oil of S. officinalis from nine European countries showed 3 to 45 percent 1,8-cineole, 11 to 29 percent camphor, 3 to 24 percent alpha-thujone, and five to 13 percent beta-thujone. A collection identified as var. angustifolia Ten. from Italy showed 39 percent alpha-thujone and 12 percent alpha-humulene. As in rosemary, the antioxidative activity is due to the content of phenolic diterpenes, particularly carnosic acid, carnosol, epirosmanol, isorosmanol, rosmadial, and methyl carnosate. Also, like rosemary, lute-olin, a flavonoid, exhibits antioxidative activity.

apple sage

The specific epithet, which means “bearing apples,” refers to the curious fruitlike, semitransparent insect galls that form on the branches. These agreeably flavored but astringent growths are sometimes candied as sage apples. Apple sage was used for cooking and medicine, along with S. officinalis and S. fruticosa, by the ancient Greeks and Romans, but apple sage does not currently have GRAS status.

The leaves of apple sage are egg-shaped with rounded- to heart-shaped bases, 2 to 3 inches (5 to 8 cm) long, wrinkled and densely hairy when young. The violet-blue flowers often have a reddish calyx.

Important chemistry: The essential oil contains 15 to 72 percent alpha-thujone, 7 to 51 percent beta-thujone, and trace to 10 percent 1,8-cineole.

clary sage

French: toute-bonne, sauge sclarée

German: Scharlei, Muskatsalbei

Italian: sclarea, erba moscatella, scanderona, trippa di dama, scarleggia

Spanish: hierba de los ojos, amaro, almaro, salvia romana

The herb’s traditional use for clearing the eyes give it the specific epithet—meaning “clear”—as well as its common name. The seeds are mucilaginous in water and were once used to pick up small particles of dirt from the eyes.

Clary sage imparts a muscatel flavor to alcoholic beverages and is used to flavor wines, vermouths, and liqueurs, so an alternative common name is muscatel sage. The essential oil is widely used in perfumery. Sclareol, an amber-scented compound present as trace to 3 percent of the oil, is isolated from clary sage by hydrocarbon extraction and is useful for tobacco flavoring. The oil of clary sage is GRAS at 1 to 155 ppm. The oil has both anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving action.

Clary sage is a biennial that readily reseeds in the garden. The winter rosette is relatively lacking in fragrance, but the entire inflorescence, rising to 39 inches (1 m) high and bearing white or pink flowers with leafy bracts, has a pronounced cloying, amber/lavender note. Leaves are broadly egg-shaped, heart-shaped at the base, about 3 to 5 inches (8 to 14 cm) long.

The var. turkestanica Mottet has been used to designate forms with long bracts, but the offerings of this variety in the seed trade differ little from normal seed lots of clary sage; seed lots of ‘Vatican’ also differ very little.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of typical clary inflorescences has 14 to 74 percent linalyl acetate, 8 to 32 percent linalool, and 2 to 12 percent alpha-terpineol. The diffusive, onion-like odor of perspiration is from trace amounts of 1-methoxyhexant-3-thiol. A lemon/rose-scented form of clary has also been isolated in Israel; this has 36 to 37 percent geranyl acetate, 16 to 25 percent geraniol, 11 to 19 percent geranial, 8 to 11 percent neral, and 1 to 0 percent germacrene D. Leaves are typically less odorous, being scented with about 68 percent germacrene D.

Salvia sclarea

bluebeard sage

The specific epithet means green, but this is known as bluebeard sage, Joseph sage, red-topped sage, or horminum clary. The sterile bracts, often colored violet, green, pink, or white, are very decorative in the garden. The leaves of bluebeard sage are egg-shaped or parallel-sided, rounded or heart-shaped at the base, blunt at the apex, and 2 inches (5 cm) long. While bluebeard sage is grown today only as an ornamental, it was once used by the Greeks and Romans to flavor wine.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of bluebeard sage contains 29 percent beta-pinene and 15 percent alpha-humulene.

Key:

1. Annual bearing brilliantly colored sterile bracts at the terminus of the branches................. S. viridis

1a. Perennial without sterile bracts....................................................................... 2

2. Leaves usually tri-lobed and velvety...................................................... S. fruticosa

2a. Leaves usually simple and not velvety............................................................. 3

3. Corolla brilliant red..................................................................... S. elegans

3a. Corolla blue, pink, or white, not red............................................................. 4

4. Leaves rounded or heart-shaped at the base................................................. 5

5. Leaves 5 to 8 cm long.......................................................... S. pomifera

5a. Leaves 8 to 18 cm long................................................................... 6

6. Hardy biennial from winter rosette............................................ S. sclarea

6a. Tender shrub............................................................... S. dorisiana

4a. Leaves narrowed to the base................................................................ 7

7. Corolla dark blue-violet; flowers many in compact, crowded clusters.... S. clevelandii

7a. Corolla blue, blue-violet, pink, or white; flowers in five- to ten-flowered clusters.... 8

8. Leaves to 5 cm long, parallel-sided............................... S. lavandulifolia

8a. Leaves 4 to 7.7 cm long, broadly parallel-sided........................ S. officinalis

S. clevelandii (A. Gray) Greene, Pittonia 2:236. 1892.

As mentioned earlier, we do not usually cultivate “pure” S. clevelandii, but rather hybrids with S. leucophylla. The hybrid differs from S. clevelandii in having lavender-blue flowers and branched hairs.

Native country: Cleveland sage is a component of the chaparral of western San Diego County, California, extending down to Baja California.

General habit: Cleveland sage grows about 1 m tall. Branchlets are hairy with backward-directed hairs, ashy.

Leaves: Leaves are 1.5 to 2 cm long, usually widest at the center with the ends equal, blunt at the apex, narrowed to the base with stalks 3 to 6 mm long, margins with rounded small teeth, the upper surfaces puckered, coated with fine hairs, the lower ashy or, especially when young, whitened with minute appressed hairs, with prominent veins.

Flowers: Flowers are many in one to three compact, crowded clusters in remotely interrupted spikes, these evenly branched, subtended by firm egg-shaped bracts shorter than the calyces. Corolla is dark violet-blue.

S. dorisiana Standley, Ceiba 1:43. 1950.

Native country: Peach sage is a native of Honduras.

General habit: Peach sage is a shrub to about 1 to 1.2 m, with long, soft, somewhat wavy hairs, leafy and freely branched.

Leaves: Leaves are egg-shaped, pinched at the tip, heart-shaped at the base with lobes often overlapping, toothed, thinly papery, hairy, gland-dotted below, 7 to 14 × 5 to 10 cm.

Flowers: Inflorescence is showy, glandular; flower cluster two- to ten-flowered; corolla is magenta, with long, soft, somewhat wavy hairs.

S. elegans Vahl, Enum. pl. 1:238. 1804 (S. rutilans Carrière).

Native country: Pineapple sage is native to Mexico.

General habit: Pineapple sage is a shrubby herb, 61 to 120 cm.

Leaves: Leaves are egg-shaped, tapering to the tip, rounded at the base, finely toothed, hairy, 2.5 to 10 cm long.

Flowers: The inflorescence is branched, flower clusters distinct, about six-flowered; corolla is deep crimson to blood red, densely coated with long, soft, straight hairs.

S. fruticosa Mill., Gard. Dict. ed. 8. 1768 (S. triloba L.f.).

Native country: Greek sage is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region.

General habit: Greek sage is a shrub to about 1 m, white-hairy.

Leaves: Leaves are usually three-lobed, the laterals much smaller than the terminal. Terminal lobe is two to four times longer than wide with the sides parallel tending to egg-shaped, 2 to 5 × 0.75 to 2 cm, wrinkled, lower surface white to velvety with dense, wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length.

Flowers: Inflorescence is branched, flower clusters two- to eight-flowered; corolla is bright blue.

S. lavandulifolia Vahl, Enum. pl. 1:222. 1804.

In 1983, De Bolòs and Vigo reclassified the subspecies of S. lavandulifolia into five forms of S. officinalis subsp. lavandulifolia (Vahl) Gams, later publishing subsp. lavandulifolia as a variety [S. officinalis L. var. lavandulifolia (Vahl) O. de Bolòs & J. Vigo, Fl. Païos Catalans 3:342. 1995], but S. lavandulifolia is maintained as a species here, following popular custom.

Native country: Spanish sage is native to central, southern, and eastern Spain, extending slightly into southern France.

General habit: Spanish sage is a small shrub or herb, woody at the base, up to 50 cm high, stems erect or ascending, hairy.

Leaves: Simple leaves are stalked, narrow, narrowly parallel-sided, edged with small rounded teeth, up to 5 cm long, with a dense, wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length.

Flowers: Flower clusters six- to eight-flowered; calyx is often reddish purple, hairy, corolla is blue or blue-violet.

S. officinalis L. Sp. pl. 23. 1753.

Native country: Garden or Dalmatian sage is native to northern and central Spain, southern France, and the western part of the Balkan Peninsula but is widely cultivated and naturalized in southern and south-central Europe.

General habit: Garden sage is a shrub to 61 cm high, stems erect, covered with dense, woolly covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length.

Leaves: Leaves are simple, stalked, parallel-sided, more or less narrowed at the base, ruffled, white-hairy beneath, greenish above, densely hairy when young, 4.1 to 7.7 × 0.9 to 5.0 cm.

Flowers: Flower clusters are five- to ten-flowered; corolla is violet-blue, pink, or white.

S. pomifera L., Sp. pl. 24. 1753 (S. calycina Sibth. & Sm.).

Native country: Apple sage is native to southern Greece and the southern Aegean region.

General habit: Apple sage is a shrub to 1 m, much-branched, short-hoary.

Leaves: Leaves are simple, stalked, egg-shaped, rounded or heart-shaped at the base, 5 to 8 cm long to about 3 cm wide, wrinkled, densely short-hoary when young.

Flowers: Flower clusters two- to four-flowered; calyx is often reddish purple with non-glandular hairs and sessile glands, corolla is violet-blue, the lower lip paler.

S. sclarea L., Sp. pl. 27. 1753.

Native country: Clary sage is native to southern Europe.

General habit: Clary sage is a biennial or short-lived perennial up to 1 m high. Stems are erect, much branched, glandular above.

Leaves: Leaves are simple, stalked, broadly egg-shaped, heart-shaped at base, hairy, about 8 to 14 × 5 to 10 cm.

Flowers: Flower clusters are four- to six-flowered. Bracts exceed the lilac or white corollas. Calyx has spiny teeth, hairy and dotted with glands.

S. viridis L., Sp. pl. 24. 1753 (S. horminum L.).

Native country: Bluebeard sage is native to southern Europe.

General habit: Bluebeard sage is an annual with stems to 50 cm, erect, simple or branched, non-glandular or glandular-hairy.

Leaves: Leaves are simple, stalked, egg-shaped or parallel-sided, rounded or heart-shaped at the base, blunt at the apex, regularly edged with round teeth, hairy, about 5 × 2.5 cm.

Flowers: Flower clusters are four- to eight-flowered. Terminal sterile bracts are usually prominent and violet, green, pink, or white. Corolla is pink or violet.

burnet

Family: Rosaceae

Growth form: herbaceous perennial to about 18 inches (46 cm)

Hardiness: hardy to Zone 5

Light: part to full sun

Water: constantly moist but not wet

Soil: well-drained garden loam rich in organic matter, pH 4.8 to 8.2, average 6.8

Propagation: seeds in fall or spring, 5,000 seeds per ounce (176/g)

Culinary use: salads but not GRAS

Craft use: none

Landscape use: front of herb or vegetable garden

French: grande pimprenelle, pimprenelle commune des prés

German: Pimpinelle, Kölbel, Blutsauge, Kleiner Wiesenknopf, Bibernelle

Dutch: klien sorbenkruid, bloedkruid

Italian: pimpinella, bilbernella, salvastrella, meloncello

Spanish: pimpinela menor

Portuguese: pimpinela

Salad burnet is one of those herbs that can shine in the garden and in the kitchen. As a landscape plant, it possesses unusual accordion-like, dark green leaves. Its lacy, ferny appearance provides texture and contrast in the herb garden. In the kitchen, burnet’s light cucumber-flavored leaves are useful in several ways. In France, the leaves are used for dressings, salads, soups, and sauces, wherever a light cucumber flavor is needed. Burnet’s decorative leaves make it especially useful as a garnish for pâtés and aspics. Burnet makes a good alternative to decorative sprigs of parsley in other dishes, too.

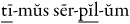

Sanguisorba minor

Burnet is easily grown from seeds planted in fall or spring and will easily reseed (the reseeded plants are often healthier than the original plants). Provide a light, well-drained organic soil in full sun with good moisture retention.

Start cutting one-year-old plants early in spring through early summer. The plant grows to 12 to 18 inches (30 to 46 cm) when flowering but normally exists as a tight rosette of leaves. Flowers are minute and green in small, tight heads; the red stigmas are often visible. To keep the plants vigorous and limit self-seeding, cut the flowers as they appear; they are good to eat but can become fibrous if cut too late.

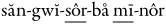

The genus Sanguisorba includes about 18 species. Some were once believed to have styptic qualities, so the generic name translates to “blood-stauncher.” The specific name translates to “small.”

In spite of centuries of consumption by Europeans, burnet has no GRAS status.

Six subspecies are known, but subsp. minor (Poterium sanguisorba L.) is the burnet of gardens.

S. minor Scop., Fl. Carn. ed. 2. 1:110. 1772.

Native country: Burnet is native to dry grassland and rocky ground, southern, western, and central Europe, extending to southern Sweden and central Russia.

General habit: Burnet is a smooth herb with a well-developed basal rosette of leaves, reaching 30 to 46 cm when flowering.

Leaves: Leaves have three to twelve pairs of globe-shaped to elliptical leaflets; each leaflet is 0.5 to 2 cm, more or less stalked, round-toothed to incised, mostly of equal size.

Flowers: The green flowers are arranged in globose to egg-shaped heads.

Fruits/seeds: The fruits are ridged or winged with pimpled and sculptured faces.

lavender cotton

Family: Asteraceae (Compositae)

Growth form: perennial subshrub to 2 feet (60 cm)

Hardiness: most hardy to Zone 6

Light: full sun

Water: moist to somewhat dry; can withstand drought when established

Soil: well-drained gravelly or rocky loam

Propagation: layerings or cuttings in summer

Culinary use: none

Craft use: tussy-mussies, potpourri

Landscape use: small, tight hedges, knot gardens

French: petit cyprès, santoline, aurone femelle, garde-robe

German: Heiligenkraut, Cypressenkraut

Dutch: heiligenbloem

Italian: santolina, crespolina

Spanish: abròtano hembra, hierba lombriguera hembra, hierba piojera, santolina, bolina, manzanilla cabezudo

Portuguese: abrotano fêmea, guarda roupa

In the landscape, the compact, short gray lances of Santolina resemble cotton balls, hence the common name “lavender cotton” or “cotton lavender” in England. The lavender cottons were used in culinary and medicinal applications at one time (particularly to rid the body of worms), but none have GRAS status. The fragrance of the plants is penetrating and unusual, and the branches are attractive for Christmas decorations, tussy-mussies, and as additions to potpourris. An old tale suggests that lavender cotton acts as a moth preventive, and the French name, garde-robe, indicates its value in closets (this French name is also applied to southernwood), but we cannot find any research to validate the efficacy of this use. The greatest value of the lavender cottons, however, is in the herb garden as hedges, especially for decorative, intricate hedges that form “knots.”

Santolina chamaecyparissus

Santolina is an example of botanists and horticulturists going about their own merry ways without communication. Names that have proliferated in catalogs and herb books either have been misapplied or have no botanical meaning. Our interpretation is the best that can be done with the existing literature.

Santolina is a genus of about twelve species of subshrubs native to the western Mediterranean region. The generic name was derived from sanctum linum, “holy flax,” an old name for green lavender cotton.

The plant cultivated as gray lavender cotton is actually one self-sterile clone that keys out to S. chamaecyparissus subsp. insularis in E. Guinea and T. G. Tutin’s account in Flora Europaea. The specific name is derived from the Greek word chamai, which means “on the ground,” and a second word, kuparissos, which translates as cypress; insularis refers to Corsica and Sardinia, where this subspecies is common. In the wild, the cultivated clone of gray lavender cotton is very rare, and our clone seems to have originated in the former Yugoslavia, according to Hugh McAllister of the University of Liverpool Botanic Garden, who has introduced other clones of this gray lavender cotton into England and has been able to effect seeds. He now proposes that since Linnaeus’ type specimen (S. chamaecyparissus subsp. chamaecyparissus) is similar to the Sardinian populations, the cultivated Yugoslavian plants should be designated as S. chamaecyparissus subsp. dalmaticum.

The plant cultivated as dwarf lavender cotton (‘Nana’ or ‘Compacta’) occurs in the wild in Majorca and Minorca in the Balearic Islands. This dwarf entity with crisped-branched hairs keys out to S. chamaecyparissus subsp. squarrosa in Flora Europaea. McAllister has proposed that this is actually a separate species, S. magonica. Another, taller-growing lax shrub with long, feathery leaves, bearing numerous lobes, originated in central Italy, and McAllister notes this should be designated as S. neapolitana, the Naples lavender cotton.

The green lavender cotton has usually been designated as S. virens but designated as synonymous with S. viridis, or S. rosmarinifolia in the horticultural literature. Yet S. rosmarinifolia (alias S. viridis) has remote leaf lobes on the juvenile foliage, thus the designation of rosemary-leaved. This species is not hardy north of Zone 8 and is not our green lavender cotton.

What, then, is our green lavender cotton? The green-leaved, almost herbaceous, creamy-white flowered, smooth plants from the Alpi Apuane northeast of Genoa key out to S. chamae cyparissus subsp. tomentosa in Flora Europaea. McAllister has designated these as a separate species, S. pinnata.

A few named cultivars are grown. Here we have tried to describe these and their taxonomic placement.

Cultivar: ‘Edward Bowles’

Origin: Hillier and Sons, England; S. neapolitana

Leaves: gray-green

Flowers: cream-yellow

Cultivar: ‘Lemon Queen’

Origin: S. pinnata

Leaves: green

Flowers: pale yellow

Cultivar: ‘Morning Mist’

Origin: S. rosmarinifolia

Growth: 15 inches (38 cm) tall; tolerant of compacted, wet soils

Leaves: grayish-waxy green

Flowers: yellow

Origin: perhaps S. magonica?

Growth: dwarf

Leaves: gray

Flowers: yellow

Cultivar: ‘Pretty Carroll’

Origin: Carroll Gardens, Westminster, Maryland; S. chamaecyparissus

Leaves: gray

Flowers: yellow

Cultivar: ‘Primrose Gem’

Origin: S. pinnata; probably the same as ‘Lemon Queen’

Leaves: green

Flowers: pale yellow

Cultivar: ‘Sulphurea’

Origin: S. neapolitana

Leaves: similar to ‘Edward Bowles’ but more gray

Flowers: pale primrose yellow

Both the gray and green lavender cottons, no matter what their names, are easily grown in full sun in sandy, well-drained soil. Pythium wilt of the foliage and sudden root wilts are problems that can be avoided with excellent drainage, good air circulation, and neutral to slightly alkaline soil. These subshrubs do best with a hard annual pruning in spring, which allows increased air circulation and permits more sunlight to penetrate the plant. In late summer the white to yellow heads (“rayless daisies”) appear; these can be removed later, but do not prune heavily at this time or the plant may die.

Most of the cultivated material produces few seeds, and the cultivars cannot be seed propagated reliably. Layering stems is the easiest route to increasing your collection of lavender cottons, but rooting summer stem-tip cuttings, although difficult, is reliable if you need many new plants. The grayer the foliage, however, the less the humidity required for rooting, and rooting of gray lavender cotton can be easily accomplished during summer under a 50-percent shade cloth if the humidity is 80 percent or above.

The oil of S. chamaecyparissus has been shown to be anticandidal.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of a plant identified as S. chamaecyparissus subsp. squarrosa from eastern Spain is dominated by 25 percent camphor and 19 percent allo-aroma-dendrene, providing a spicy-camphoraceous odor. French oils of S. chamaecyparissus are dominated by 31 to 34 percent artemisia ketone and 9 to 18 percent beta-phellandrene, providing an odor of annual wormwood (sweet Annie). German and Hungarian oils of S. chamaecyparissus are dominated by 17 percent longiverbenone (vulgarone B), providing a dusty miller–like odor similar to some forms of Artemisia doug-lasiana. The essential oil of plants identified as S. chamaecyparissus from Turkey has 38 perc-cent artemisia ketone, 12 percent camphor, and 9 percent beta-phellandrene with an artemisialike odor. Cultivated plants of S. chamaecyparissus in India have 32 percent artemisia ketone, 16 percent 1,8-cineole, and 15 percent myrcene. Plants identified as S. rosmarinifolia from Bulgaria have 14 percent beta-eudesmol and 13 percent 1,8-cineole in the essential oil of the flower heads, providing a eucalyptus-like odor.

Key:

1. Leaves green to grayish-waxy green, not hairy........................................................ 2

2. Leaves green; flowers whitish.............................................................. S. pinnata

2a. Leaves grayish-waxy green; flowers yellow........................................... S. rosmarinifolia

1a. Leaves gray, finely hairy.............................................................................. 3

3. Leaves feathery in appearance with numerous, long lobes......................... S. neapolitana

3a. Leaves knobby in appearance with short lobes................................................. 4

4. Peg-like lobes of leaves not more than 2 mm, eight to nine per longitudinal row................................................................................................. S. magonica

4a. Peg-like lobes of leaves at least 2.5 mm, nine to fourteen per longitudinal row............................................................................................ S. chamaecyparissus

S. chamaecyparissus L., Sp. pl. 842. 1753 [S. chamaecyparissus L. subsp. insularis (Genn. ex Fiori) Yeo, S. incana Lam.].

The clone in cultivation is S. chamaecyparissus subsp. dalmaticum.

Native country: Gray lavender cotton is native to Sardinia and the former Yugoslavia.

General habit: Gray lavender cotton is an erect to ascending subshrub.

Leaves: Leaves are densely toothed and coated with a dense wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length; lobes are more than 2.5 mm long.

Flowers: Head is usually coated with hairs like the leaves. Flowers are yellow.

S. magonica (Bolòs, Molin. & P. Monts.) Romo, Flores Silvestres Baleares 303. 1994.

Native country: Dwarf lavender cotton is native to the Balearic Islands and perhaps North Africa.

General habit: Dwarf lavender cotton is an erect to ascending subshrub.

Leaves: Leaves are smooth to coated with a dense wool-like covering of matted, crisped-branched hairs of medium length; lobes are no more than 2 mm long.

Flowers: Head is usually smooth. Flowers are pale yellow.

S. neapolitana Jord. & Four., Icon. fl. eur. 2:10. 1869.

Native country: Naples lavender cotton is native to central Italy.

General habit: Naples lavender cotton is an erect to ascending subshrub 30 to 61 cm tall and 61 to 91 cm wide.

Leaves: Leaves appear feathery with long numerous lobes and are coated with a dense wool-like covering of matted hairs of medium length.

Flowers: Head is coated with hairs like the leaves. Flowers are yellow.

S. pinnata Viviani, Elench. pl. hort. Dinegro 31. 1802 [S. chamaecyparissus L. subsp. tomentosa (Pers.) Arcangeli, S. ericoides].

Native country: Green lavender cotton is native from the Pyrenees to central Italy.

General habit: Green lavender cotton is an erect or ascending subshrub.

Leaves: Leaves are green and smooth with lobes 2.5 to 7 mm long.

Flowers: Head is usually smooth. Flowers are whitish to pale yellow.

S. rosmarinifolia L., Sp. pl. 842. 1753.

Native country: Rosemary-leaved lavender cotton is native to the Iberian Peninsula and southern France.

General habit: Rosemary-leaved lavender cotton is an erect or ascending subshrub, 35 to 45 cm high.

Leaves: Leaves are grayish-waxy green. Juvenile leaves are erect to erect-deflexed, narrowly linear, tapering to the tip, very shortly and remotely pimpled-toothed to lobed. Adult leaves have closely pressed teeth, the uppermost smooth.

Flowers: Flowers are bright yellow.

sassafras

Family: Lauraceae

Growth form: tree to 66 feet (20 m)

Hardiness: hardy to Maine (Zone 5)

Light: full sun

Water: moist but not constantly wet

Soil: well-drained and rich in organic matter

Propagation: seeds in fall

Culinary use: root bark toxic; leaves as flavoring and thickener in soups

Craft use: potpourri

Landscape use: vigorous tree for fall color

French: sassafras

German: Sassafras, Fenchelholz

Dutch: sassafras, venkelhout, zweethout

Italian: sassafraso

Spanish: sasafras

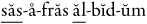

Sassafras is a rapidly growing but short-lived tree found in young forests from the U.S. Midwest to New England to the Deep South. When mature, the tree may reach more than 66 feet (20 m) high. Its fall plumage radiates brilliant orange and crimson. The root bark has the unmistakable aroma of root beer, the leaves have a fatty lemon odor, and the birds are drawn to the small, black, olive-like fruits, which they avidly consume.

Sassafras was apparently a vernacular name used by early European settlers in Florida. The specific name, albidum (“white”), refers to the blue-green smooth-to-hairy undersides of the leaves. Two other species of Sassafr as grow in China, S. tzumu (Hemsley) Hemsley and S. randaiense (Hayata) Rehder.

Sassafras roots and leaves are usually gathered from the wild. If you cultivate sassafras in your garden, start it from seed or transplant seedlings very early before the taproot develops; transplanting later is difficult. Soil should be well drained but rich in organic matter and in full sun.

Sassafras albidum

Sassafras has been a tree of many uses. The tea from the root bark, mixed with milk and sugar, was once consumed as a beverage called saloop, and the root bark was used to brew root beer. The chief constituent of the roots, safrole, has been prohibited by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 1960 in foods because it is metabolized to a liver toxin and carcinogen. Yet, sassafras root tea is still sold (the FDA does not have enough time and money to police every farmers’ market) and has many adherents as a “blood-purifier.”

Other health conditions have been tied to sassafras tea; overindulgence (about ten cups a day for an adult) has been linked to a medical condition called diaphoresis that is characterized by profuse sweating with an elevated body temperature. Consumption of as little as 0.17 ounces (5 ml) of sassafras oil may kill an individual or induce vomiting, tachycardia (irregular heartbeat), and tremors. While you may or may not personally accept the toxicity and carcinogenicity of sassafras roots and safrole, you may be sued by someone who becomes ill or develops liver cancer if you sold them or advised the consumption of safrole-rich beverages or foods. Lawyers from the FDA could also be petitioned as a witness for the litigant.

The controversy over the safety of sassafras arises from the long consumption of sassafras root tea by the Appalachian community and because safrole itself is not carcinogenic. However, safrole is metabolized to very active carcinogens in the body on ingestion. Complicating matters in the ban on sassafras tea is that safrole is also present in trace quantities in some spices, such as nutmeg (0.12 to 0.43 percent safrole) and mace (0.43 to 1.99 percent). However, these levels are considered relatively minor, and so the FDA does not prohibit nutmeg and mace; both spices are also consumed daily in beverages and foods at levels below that of routine sassafras root tea drinkers.

The FDA does approve safrole-free extracts of sassafras at 10 to 290 ppm, while the leaves, known as filé, are GRAS at 30,000 ppm. Artificial sassafras oil is safrole-free and relatively safe, based upon wintergreen. Filé, or gumbo filé (from the Choctaw kombo ashish), is used in Cajun cooking, sometimes mixed with other herbs and spices, as a thickener and flavoring in soups and stews. Add the filé at the last few minutes of cooking or else a stringy mass will result (the French filé means thread). The egg-shaped or two- to three-lobed (“mitten-shaped”) leaves may be ground fresh or dried and powdered for later use. Fortunately safrole is either absent or present in only trace levels in sassafras leaves.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of the roots of sassafras contains 74 to 80 percent safrole, providing a warm-spice, woody-floral odor. The essential oil of the leaves has around 30 percent (Z)-nerolidol, 22 percent beta-caryophyllene, and 20 percent linalool, providing a woody-floral, green odor, sometimes with various fatty acids that provide a sour-fatty note. The young twigs of sassafras have an essential oil with around 27 percent limonene, 24 percent linalool, and 16 percent alpha-terpineol, providing a sweet lemony odor.

S. albidum (Nutt.) Nees, Syst. laur. 490. 1836.