It lives on as the truest, cruelest picture of the growth of the Middle West and the liveliest portrait left to us of the people who made it grow. It’s better than a good book.

None other of Orson Welles’s films so explicitly concerns the transformation of a city as The Magnificent Ambersons. For his second feature production, Welles was again able to exploit RKO’s studio resources to reimagine American urban history on screen. This time a much larger percentage of the budget was devoted to the construction of elaborate and spatially comprehensive sets.2 He worked with a new art director and cinematographer, respectively Mark-Lee Kirk and Stanley Cortez, and although the results were spectacular, the collaboration proved a less happy experience for Welles than the Kane collaboration with Ferguson and Toland. He eventually fired Cortez, supposedly for slowness, and the film went substantially over budget.3

Welles had typically loaded himself with projects following the May 1941 release of Citizen Kane. He’d already adapted Arthur Calder-Marshall’s recent thriller The Way to Santiago, and had commissioned draft scripts for segments of his gestating anthology film It’s All True. In the summer, at RKO’s request, Welles and Joseph Cotten co-wrote an adaptation of Eric Ambler’s thriller Journey into Fear. Welles later denied he was ever going to direct that film, but it seems to have been his original plan.4 He was also developing a script based on the case of the French serial wife-murderer Henri Désiré Landru that later became Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947). In September ‘My Friend Bonito’, an episode of It’s All True, began production in Mexico under the supervisory direction of Norman Forster. Welles had visited Mexico briefly that month before the shoot and intended to share a co-directing credit with Foster.5 From 15 September he produced, directed, and starred in The Orson Welles Show, a weekly CBS radio variety programme.

Welles had already adapted Booth Tarkington’s novel The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) for a 1939 Campbell Playhouse radio broadcast. Welles’s final script for the film adaptation was dated 7 October 1941, three weeks before the commencement of production. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December changed Welles’s priorities and forced him to re-evaluate his current film commitments. Nelson Rockefeller, who headed the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) under President Roosevelt, asked Welles to travel to South America in early February as a Good Will Ambassador for the Good Neighbor Policy. Rockefeller was also a stockholder on the RKO board of directors. In response to a request from the Brazilian government, the OCIAA invited Welles to film Rio de Janeiro’s 1942 Carnaval. Welles decided to incorporate this mooted Carnaval documentary into his evolving It’s All True, which now obtained United States government co-sponsorship, with the OCIAA guaranteeing $300,000 against any RKO losses. Welles would work in South America without a salary, although his expenses would be paid. The idea was to strengthen Pan-American unity against fascism.6

Rio’s Carnaval would start on 8 February, so Welles had to finish his Hollywood work ahead of schedule. Norman Foster was brought back to the United States just before Christmas, which forever postponed completion of ‘My Friend Bonito’. He was assigned to direct Journey into Fear starting 6 January. Welles performed his supporting role as Colonel Haki at night while continuing to film on The Magnificent Ambersons by day.

Principal photography of Ambersons wrapped on 22 January, with a few additional shots made in the days before Welles left Hollywood on 2 February. For three days in Miami, with the clock ticking down to his departure to Brazil, he worked on post-production with editor Robert Wise. The studio agreed to send Wise to Brazil to work on the film with Welles, but this proved impossible during wartime.7

On 11 March Wise sent a 131-minute print of Ambersons to Rio de Janeiro.8 A typed cutting continuity of this lost version – a shot-by-shot transcription of the editing – was made at RKO on 12 March.9 The continuity has survived as the most detailed record of the longest version of the film before it was altered, partially reshot, and progressively shortened by RKO.

Whereas Kane uses a multiple flashback structure to dance across its seventy years of history, the action of The Magnificent Ambersons progresses chronologically from 1885 to 1912, with a narrator – Welles himself – looking back from the vantage of a modernity positioned somewhere between 1918 and 1942. Like Tarkington’s, Welles’s narrator makes a direct identification with the audience.

The 131-minute version begins in 1884 when Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten), experimenter in automobiles, embarrasses himself attempting to woo Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello) with a serenade: he falls drunkenly through his bass viol under her window. Isabel’s fragile sense of propriety is offended and she marries instead the dull Wilbur Minafer (Don Dillaway). The town gossip predicts the offspring of this loveless marriage will be the “worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see”. As it turns out, there is only one child, a “princely terror” named George Amberson Minafer. George’s childhood fights with the townsfolk are gently tolerated by his weak parents. In 1902 George (Tim Holt) returns from school and demonstrates his bullying arrogance in retaking leadership of the ‘Friends of the Ace’ society.

Two years later the Ambersons host a Christmastide ball in honour of George, home from his sophomore year at college. At the ball Isabel is reunited with Eugene, by now a successful businessman in the emerging automobile industry. A widower, he introduces his pretty daughter, Lucy (Anne Baxter). Eugene and Isabel are chastely entranced with one another, and George in turn attempts to court Lucy, all the while condescending to her father and his involvement in automobiles.

Wilbur dies shortly after Christmas. His spinster sister Fanny (Agnes Moorehead), who lives with the Ambersons, mourns both her brother and her lost chance with Eugene now that Isabel is free. The next year Fanny is dismayed by Isabel’s closeness with Eugene. George and Isabel’s brother Jack (Ray Collins) tease that Eugene is really scheming for Fanny’s hand and drive her to tears. Meanwhile, the patriarch, Major Amberson (Richard Bennett), has begun to subdivide the grounds of his estate, to his grandson George’s horror and bewilderment.

Lucy refuses to accept George’s proposal of marriage because of his disdain for work and lack of ambition. George interprets this as the imposition of her father’s values, and later fantasises that Lucy grovels in apology to him and renounces her father. During a dinner, George insults Eugene indirectly by dismissing the very invention of the automobile. Eugene is unruffled, ambivalent himself about the technology’s effects on civilisation.

Fanny approves of George’s attack on Eugene; she chooses to interpret it as a defence of his mother’s reputation against unseemly town gossip. The self-obsessed George has been ignorant of talk that the romance between Isabel and Eugene preceded Wilbur’s death – ignorant, it turns out, of any romance at all. Absurdly over-sensitive about his family’s reputation, George attacks Mrs Johnson, the town gossip, and is resolutely against his mother’s marriage to Eugene. He bars Eugene from visiting Isabel and demands she renounce her true love. Uncle Jack cannot persuade George to butt out. Isabel agrees to depart with her son for a long period abroad. When George farewells Lucy, she feigns cheerful ignorance of George’s manoeuvers.

In 1910 Jack Amberson relays the news to Eugene and Lucy that Isabel has fallen ill during her long absence. When Isabel returns to Indianapolis that year, she is close to death. George once again prevents Eugene from seeing her. She dies, followed shortly by her elderly father.

The Amberson finances are in disarray. Major Amberson died without having deeded the mansion to his children, and Jack and Aunt Fanny have each lost their own money investing in a headlamp company. In 1911 the remaining three must vacate the mansion. Jack departs by train to Washington to find a consulship that will see out his remaining days. As George walks home from the station, he is shocked by the ugly, empty, alien city. In the lonely mansion he begs forgiveness of his dead mother. Then Fanny hysterically reveals she is broke. In order to support Fanny’s upkeep at her preferred boarding house, George abandons a low-paid but respectable job at a law office to take an immediately lucrative job dealing with dangerous chemicals.

Meanwhile, Lucy has renounced romance and decided to live with her father. In 1912, George is hit by a car and laid up in hospital. Eugene hears the news while in his factory. We see him enter and leave the hospital, then proceed to Fanny’s boarding house. Eugene tells Fanny that George has asked for forgiveness. It also seems Lucy and George will now be married after all. Fanny is listless and disinterested. Eugene leaves the boarding house alone.10

* * *

This lost and longest version of The Magnificent Ambersons, which has become the Holy Grail for film lovers, can only be considered a provisional cut based on Welles’s instructions as of early March. In fact, before Welles had received his copy of this print, on which he intended to base his editorial responses, he had already requested the deletion of the long section spanning the years 1905 to 1911, probably in response to the studio’s complaints about the film’s length. The exile of George and Isabel would be replaced by a short new bridging scene to be directed by Wise: Isabel would die suddenly in 1905 after George’s refusal to give his blessing to her marriage. Welles obtained a print of Wise’s new scene before 25 March, when he wrote to his business manager, Jack Moss, to criticise its quality. He asked for Norman Foster to reshoot the scene.

Meanwhile, a different version running 110 minutes – three scenes had been removed at the request of George Schaefer – was prepared for a 17 March preview in Pomona, California. The film was presented as part of a double bill with a patriotic musical, The Fleet’s In, and a concluding in-person appearance by actor James Cagney. The audience’s comment cards in response to the Ambersons preview were mixed, although the negative comments and the general atmosphere discouraged RKO’s executives.11

A second preview in Pasadena on 20 March seems to have reverted to the 131-minute version. Despite the more enthusiastic audience reception, RKO maintained that the film needed substantial revision before release. Ultimately RKO, in the middle of an executive power struggle, relied upon Wise, Cotten, Moss, and first assistant director Freddie Fleck – all Welles associates now working independently and counter to his instructions – to write and direct eleven minutes of replacement scenes. From afar Welles tried to retain authority, but RKO mostly ignored him. The final cut of the film – the only one to have survived – is a mere 88 minutes. Many of Welles’s surviving scenes were altered, shortened, or moved to different places within the film’s structure. Inferior new music by Roy Webb supplemented what remained of Bernard Herrmann’s score; the loyal and uncompromising Herrmann insisted his name be removed from the credits. The non-Welles elements only diminish the film’s dramatic power, coherence, and continuity. The film was approved for release and premiered in Welles’s absence on 10 July 1942, on a double bill with the slightly less ambitious Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost. By then Shaefer had been ousted from his position as studio head.12 His successor, Charles Koerner, ordered the destruction of Amberson’s outtakes later that year.13 The 131-minute print sent to Welles was left behind in Rio and languished for a time at Cinédia Studios. It was probably destroyed in line with RKO’s instructions around 1945.14

Ambersons – like all of Welles’s subsequent Hollywood films except for the two versions of Macbeth (1948 and 1950) – is impossible to consider a finished work by Orson Welles. But thanks to the investigative work of Peter Bogdanovich, Robert L. Carringer, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and others, extensive documentation about the longest version has been recovered and published. This research has drawn on the shooting script, the cutting continuity, still photographs, and frame enlargements from the cut sequences. Bernard Herrmann’s complete score manuscript also survived and has been re-recorded commercially.

Many of the cuts and alterations by RKO weakened the status of Ambersons as a city film. Mostly faithful to the Tarkington novel, the provisional 131-minute version maintained emphasis on the transformation of the material structures of Indianapolis amid the rise of the automobile. The RKO release version diminishes that emphasis. Fortunately Wise retained the dinner scene where the characters discuss the impact of automobile-based suburbanisation on real estate values in the old town centre, undoubtedly because it is a key moment in the dramatic conflict between George and Eugene. The film’s other reflective moments about the changing urban landscape were deemed least essential to the basic story of a wealthy family evaporating amid death and financial ruin.15

These deletions include discussions between Isabel, Lucy, George, Jack, and Fanny as they ride in Eugene’s automobile through the snow on the outskirts of town at Christmas, 1904. Their distance allows a perspective on its changes:

ISABEL: When we get this far out you can see there’s quite a little smoke hanging over town.

JACK: Yes, that’s because the town’s growing.

EUGENE: Yes, and as it grows bigger it seems to get ashamed of itself, so it makes that big cloud and hides in it.

ISABEL: Oh, Eugene.

EUGENE: You know, Isabel, I think it used to be nicer…

As they drive on George notices that “those fences are smeared!”

LUCY: That must be from soot.

FANNY: Yes … there’re so many houses around here now.

GEORGE: Grandfather owns a good many of them, I guess … for renting.

FANNY: He sold most of the lots, George.

GEORGE: He ought to keep things up better. It’s getting all too much built up. Riffraff! He lets … these people take too many liberties. They do anything they want to…

The subplot concerning the gradual subdivision of Major Amberson’s estate was almost entirely cut. Following the surviving scene in the Amberson kitchen, after George and Jack tease Aunt Fanny about Eugene’s intentions, George was to have been startled by a vision through the window. He runs into the rain to examine “excavations under the raging storm, partly erected buildings in the background”. Uncle Jack follows in pursuit.

GEORGE: What is this? Looks like excavations… Looks like the foundations for a lot of houses! Just what does grandfather mean by this? (He rushes toward the building sites, Jack following.)

JACK: My private opinion is he wants to increase his income by building these houses to rent. For gosh sakes, come in … out of the rain…

GEORGE: Can’t he increase his income any other way but this?

JACK: It would appear he couldn’t. I wanted him to put up… (Jack tries to put up an umbrella over both of them.) … an apartment building instead of these houses.

GEORGE (shouting): An apartment building! Here!

JACK (shouting): Yes, that was my idea.

GEORGE (shouting): An apartment house! (George looks to right, shocked, water streaming down his face.) Oh, my gosh!

JACK (off): Don’t worry … your grandfather wouldn’t listen to me, but he’ll wish he had, some day.

GEORGE: But why didn’t he sell something or other, rather than do a thing like this?

JACK: I believe he had sold something or other, from time to time.

George is ignorant of the family’s declining wealth. Major Amberson’s speech on the town “rolling right over” his heart survived in RKO’s version, but a few lines of subsequent conversation with Jack were cut. The Major complains about “those devilish workmen yelling around my house and digging up my lawn”. Jack advises: “When things are a nuisance, it’s a good idea not to keep remembering ’em.” That elected obliviousness proves to be the Amberson style, and it will be their downfall. Also cut: in 1910, during George and Isabel’s absence, Major Amberson and Aunt Fanny sit on the porch of the mansion and observe those houses recently built on Amberson property:

MAJOR: Funny thing – these new houses were built only a year ago. They look old already … cost enough money, though… I guess I should have built those apartments, after all.

FANNY: Housekeeping in a house is harder than in an apartment.

MAJOR: Yes. Where the smoke and dirt are as thick as they are in the Amberson Addition, I guess the women can’t stand it. Well, I’ve got one painful satisfaction – I got my tax lowered.

His satisfaction is painful because the tax reduction merely reflects the decline in the overall value of his properties. Prices are high in the periphery of the growing city where Eugene and Lucy live, and also apparently in the town centre, but not in the declining Amberson Addition.

Dialogue was changed in the sequence where Jack visits Eugene and Lucy in their “Georgian instead of nondescript Romanesque” version of the Amberson Mansion in the upland Indianapolis suburbs. Jack was to have originally commented on the inner-city pollution the Morgans had escaped. George’s last walk home to the mansion through the “strange streets of a strange city” was shortened, and the final sequence was completely rescripted and reshot to eliminate Eugene and Fanny’s talk in the boarding house, and the grim shots of Eugene driving away into the anonymity of the twentieth-century city.

* * *

That small city, the Indianapolis where I was born, exists no more than Carthage existed after the Romans had driven ploughs over the ground where it had stood. Progress swept all the old life away.

Tarkington’s Magnificent Ambersons is the middle novel between The Turmoil (1915) and The Midlander (1923) in a trilogy he later republished in a single volume called Growth. Tarkington was born in Indianapolis in 1869. The city began to rapidly transform around the time he reached maturity. His comparison with the razing of Carthage was hyperbole, of course, but of a piece with Tarkington’s conservative myth of Indianapolis’s decline.

The Turmoil begins with a racist and apocalyptic rant against the spirit of ‘Bigness’ that had flooded a midland city with new people: “The negroes came from the South by the thousands and thousands, multiplying by other thousands and thousands faster than they could die.” Immigrants came from across the world; Tarkington itemises twenty-three nationalities or races and adds “every hybrid that these could propagate. And if there were no Eskimos nor Patagonians, what other human strain that earth might furnish failed to swim and bubble in this crucible?” The modernising streets were soon filled with “a cockney type […] a cynical young mongrel barbaric of feature, muscular and cunning”.17

African-Americans, long-time residents of Indianapolis, play no crucial part in the novel of The Magnificent Ambersons. Stereotypical “darkey” servants are mere cheerful period detail, recalled in a narrative voice that consequently excludes a black readership. Ambersons won the Pulitzer Prize and was a bestseller, making its appeal to the nostalgia of a white, middle-class readership for an idealised pre-urban way of life. For most of that initial readership, the 1880s and 1890s were still within living memory. That topicality probably explains the book’s relative obscurity by 1942.18

While Welles remained a great admirer of Tarkington’s fiction, he was aware of the author’s limitations. He admitted in 1970 that Tarkington’s children were “hopelessly dated now” in comparison to the characters of Mark Twain, “who wasn’t writing about children in a middle-class atmosphere […] on Main Street under the shadow of the elms”.19 But Welles claimed on several occasions that his father had been Tarkington’s friend and that it had “long been a family assumption that the author had my father in mind when he created [the character Eugene Morgan]”.20 No evidence has emerged beyond Welles’s anecdotes to support a record of this friendship or inspiration, but Welles clearly found a deeply personal resonance in Tarkington’s novel. On several occasions Welles recalled childhood visits to the town of Grand Detour, Illinois, where his father ran the Sheffield Hotel. It was the “one place” he desired to return:

Where I do see some kind of ‘Rosebud’, perhaps, is in that world of Grand Detour. A childhood there was like a childhood back in the 1870s. No electric light, horse-drawn buggies – a completely anachronistic, old-fashioned, early-Tarkington, rural kind of life […] Grand Detour was one of those lost worlds, one of those Edens that you get thrown out of. It really was kind of invented by my father. He’s the one who kept out the cars and the electric lights. It was one of the ‘Merrie Englands.’ […] I feel as though I’ve had a childhood in the last century from those short summers.21

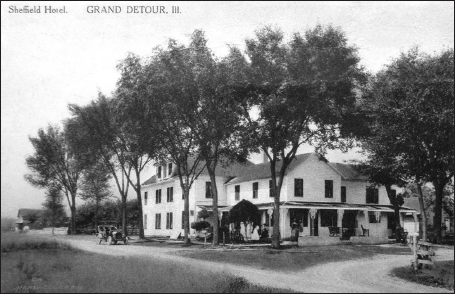

The Sheffield Hotel in Grand Detour, Illinois owned by Richard Head Welles and destroyed by fire in 1928

Welles probably confounded his followers on the left with this nostalgic, tender, and vastly forgiving reverie on declining nouveau aristocracy from a firmly bourgeois and, even by 1942, antiquated point of view. It is true that Welles’s narration, judiciously edited from Tarkington’s own third-person text, is given enhanced irony in the early scenes when juxtaposed with comic images of the town’s customs. But except for its conclusion and avoidance of the book’s overt racism, the 131-minute version of Ambersons is a faithful adaptation of Tarkington’s novel. Welles’s film acquiesces to Tarkington’s conservative myth of the midland town’s “spreading and darkening” into a city. It’s an indication of Welles’s priorities in adaptation.

The power of Welles’s drama overcomes a nagging question: why is the passing of the Ambersons’ “magnificence” worth lamenting? The family contribute little to the city apart from symbol, spectacle, and ritual. Uncle Jack Amberson is only a US congressman because “the family always like to have somebody in congress”, according to George. Eugene’s uncritical, decades-long glorification of Isabel Amberson is a mystery. Superficial in her early rejection of him for his drunken serenade, she verges on idiotic in her vague passivity. Aunt Fanny Minafer is emotionally warped by bitterness, vindictiveness, and self-pity. And George is no more than an uncritical vehicle for his class’s prejudices – certainly no tragic hero.

The decline and fall of this short-lived nouveau aristocratic family – three generations and bust – is the surface melodrama pasted onto the story of the transforming midland town. The cause of the Ambersons’ fall is their obliviousness to the coming of modernity. Major Amberson makes some effort to stave off the family’s financial decline when with reluctance he subdivides his estate in the Amberson Addition. Everybody else, except for the sardonic realist Jack, is oblivious to the changes until they hit hard. George’s “come-upance” is merely the vanishing of his wealth and privilege and his alienation from the modern city.

Welles’s lost conclusion wildly departs from Tarkington’s silly fantasy of Eugene contacting the dead Isabel through a medium. The final scene of the film was probably the reason Joseph Cotten negatively assessed the mood of the film as “more Chekhov than Tarkington”.22 Eugene visits Fanny in her run-down boarding house and, as Welles later described it,

There’s just nothing left between them at all. Everything is over – her feelings and her world and his world; everything is buried under the parking lots and the cars. That’s what it was all about – the deterioration of personality, the way people diminish with age, and particularly with impecunious old age. The end of the communication between people, as well as the end of an era.23

This conclusion seems to have left a powerfully bleak impression at the previews – the obliteration of people by the growth of a modern city – and RKO refused to accept it.

* * *

Ambersons is not a western – it might be considered the finest example of a Midwestern – but it adapts a key trope from the genre. The coming of the transcontinental railroad to the frontier had been “the dominant symbol of progress” in westerns such as The Iron Horse (John Ford, 1924), The Union Pacific (Cecil B. DeMille, 1939), and Dodge City (Michael Curtiz, 1939).24 In Kane the railway connects the Colorado frontier back east to Chicago and New York, to the moneyed soullessness represented by Thatcher. The coming of the automobile to Indianapolis in Ambersons has the same symbolic function as the herald of modernity.

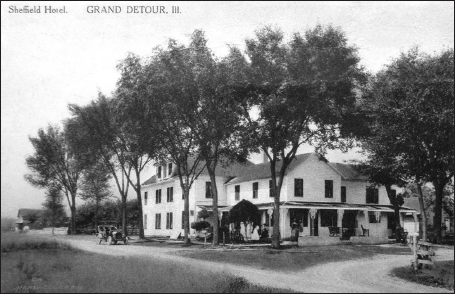

Welles created Indianapolis’s ‘National Avenue’ at the RKO Ranch in the San Fernando Valley.25 Like the few exterior street sets in Kane, the avenue has the slightly artificial appearance of a Hollywood backlot. Welles enlivens the mise-en-scène by emphasising various period-signifying components of the streetscape. The scenes of the turn of the century employ generic motifs of the western: a wagon wheel, the period costumes of the townsfolk, the town’s bank and hardware store, and one of several horse-drawn carts George drives in the movie.

The town in 1894 (figs 1–2) and 1902 (figs. 3–4)

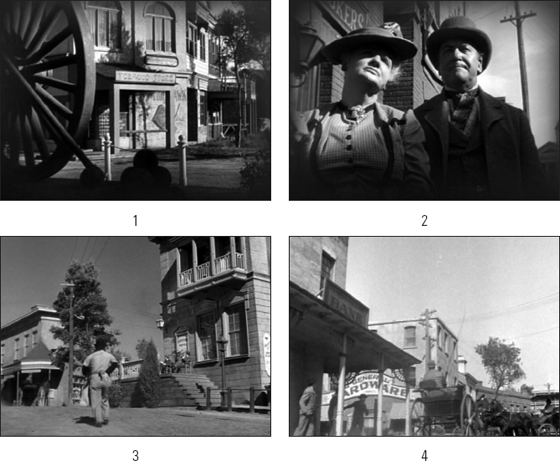

For the later scenes in 1905 and 1912, National Avenue is modernised with automobile traffic and picture theatres.26 The soundscape was designed to increasingly register the noises of automobiles.27

Tarkington never directly identifies the novel’s setting as Indianapolis, but the fictional midland town is universally regarded as a personal reimagining of his birthplace.28 In his film adaptation, Welles directly identifies the city only once by a brief insert shot of an Indianapolis Inquirer headline. That insert also features a cameo by Kane’s Jedediah Leland, by-lined and pictured above his dramatic column. It is the sole intertextual hinge between Welles’s two American history films.

Indianapolis, 1905

The city by the White River was chosen in 1820 as the state capital in the mistaken belief that the river was navigable for transport. The plan for the capital was conceived around institutions of government, with the governor’s house at its centre. Indianapolis’s emergence as a commercial nexus followed in the middle of the nineteenth century. This has been attributed to the construction of interurban railroads which linked Indianapolis to the Ohio River; it eventually became the ‘hub of the wheel’ and so assumed a dominant commercial role in the state.29

In the middle of the century the population swelled. As of 1860, at least twenty per cent of the population was foreign-born, immigrants mainly from Germany and Ireland.30 The interwar half-century between 1865 and 1917 saw a vast transformation in Indianapolis’s industrial economy, demographics, and physical infrastructure. Booth Tarkington explicitly cites the year 1873 as the beginning of the Amberson family’s “magnificence”, a particularly short social dominance of less than forty years. The novel’s first line describes how in that year “Major Amberson had ‘made a fortune’ when other people were losing fortunes.” Tarkington was referring to the Panic, an international recession that plunged Indianapolis into economic stagnancy for fifteen years and probably contributed to the preservation of its mid-nineteenth-century social hierarchy.31

Economic growth restarted with the discovery of natural gas in north central Indiana in the late 1880s; Indianapolis lurched towards becoming a centre of manufacturing. The city pushed through a recession in the mid-1890s to expand until the end of the century. As the gas supply declined, so did the Indianapolis economy, but the decline was partly stalled by two factors: the city’s centrality to the interurban railway network and the growth of a local automobile industry.32 Indianapolis became a representative Midwestern site of a dynamic historical antagonism: different modes of interurban and intraurban transport would compete for the next century to drag the cityscape towards conflicting material forms.33

In other words, Indianapolis experienced waves of growth and decline, and the periodic realignment of its industrial resources in a changing America. The physical infrastructure of the city changed in response to industry, technologies, and a growing population.

The period just before World War I was the peak of Indianapolis’s railways – an average of four hundred electric interurban trains arriving and departing every day in 1910. But these services dropped away as the Midwest banked its future on the automobile.34 Major automobile firms including Ford, Stutz, and Duesenberg produced cars in Indianapolis.35 The city was for a time the production centre of shock absorbers.36 The world-famous Indy 500 race was established in 1911. Indianapolis’s material cityscape continued to change as the automobile grew in dominance. Electric streetcars replaced horse-drawn cars in the 1890s. A 1913 strike by streetcar workers led to riots, a police mutiny, and the imposition of martial law. The streetcars endured until 1953.37 The increase in private traffic in the early twentieth century had demanded the replacement of gravelled streets with expensive hard surfaces. To protect this municipal investment in roads, the city had to take control of underground utilities.38

City transit had been a background issue in Kane, just one of Kane’s social crusades, but in Ambersons it defines the shape of the city and the economic fortunes of its citizens. Ambersons argues for technology’s transformative power and laments its casualties.

* * *

In Welles’s Ambersons Indianapolis is reduced to National Avenue, the Amberson Mansion and its surroundings in the Amberson Addition, the city’s train station, Eugene Morgan’s house and factory, the rural outskirts of town, and finally Fanny’s boarding house.

Welles’s narrator, like Tarkington’s, takes on the retrospective point of view of Indiana’s middle class. The opening shots, however, paradoxically assume the point of view of the Amberson Mansion itself, looking across the street to the less magnificent house of Mrs Johnson, who will years later be censured by George for spreading gossip about his mother (Mrs Johnson appears to be the woman who hollers for the horse-drawn streetcar).

The opening sequence of the 131-minute version maintained this point of view and framing across four successive shots, creating a time lapse of the Johnson house in the dress of different seasons and times of day. This is a variation of the opening of Kane, where Xanadu looms in a succession of progressively closer shots, always with Kane’s lighted window occupying the same pivotal position in the upper right of the frame – a spatial lapse rather than a temporal one. In Ambersons, Eugene’s disastrous serenade intrudes into the summer shot. He rushes into the foreground and the fixed shot pans slightly downwards to take in his spectacular fall backwards through the bass fiddle; the counter-shot representing his point of view up towards Isabel Amberson’s window establishes his location in the Amberson’s front garden. The time lapse depicting the Johnson house was interrupted by RKO’s reordering of the early sequences: the survey of the period’s fashions was interpolated between the Johnson house’s autumn and winter.

The Johnson house

In the novel the Amberson Mansion is the residence of Major Amberson. Isabel and Wilbur live in a nearby house. Welles relocates the whole family inside the same impressive residence, a dramatically efficient change. The exteriors of the mansion on Amberson Boulevard were shot at the RKO Ranch with a false front and a matte painting. The mansion also appears in several back projections.39

As in Kane, much of the action of Ambersons centres on a house that is a symbolic expression of personality. The interior designs of the mansion were based on photographs in a publication called Artistic Houses; Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States (1883–1884).40 The set was constructed at the RKO-Pathé Studio in Culver City. Welles would never again have such large financial resources to build sets. That limitation led to creative solutions and helped determine his later aesthetics.

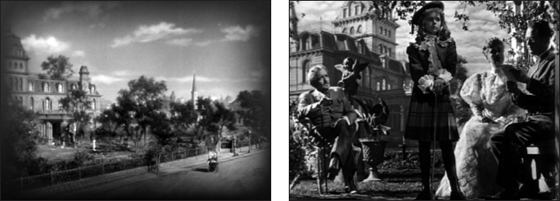

The Amberson mansion embellished by a matte painting; and with back projection

Welles’s long sequence at George’s Christmastide ball, comprising several elaborate tracking shots, would have taken the audience from the mansion’s front door and upstairs through all three storeys. The many interwoven conversations and asides establish the leading characters and set in action both Eugene and Isabel’s renewed fascination and George’s courtship of Lucy. RKO’s cuts to this sequence diminish the mansion’s spatial coherence.

Welles assigned Stanley Cortez to film another long and difficult tracking shot that would have represented George’s subjective point of view as he entered the mansion after his ‘last walk home’ from the train station. On this occasion Welles seems to have rejected the shot from the outset, because it does not appear in the continuity of the 131-minute version.

* * *

Around 1800 [sic] Major Amberson had bought two hundred acres of land at the end of National Avenue; through this tract he had built broad streets and cross-streets, paved them with cedar block, and curbed them with stone. He set up fountains, here and there and at symmetrical intervals placed castiron statues, painted white. And all this Art showed a profit from the start. The lots had sold well and there was a rush to build in the new Addition. Its main thoroughfare was called Amberson Boulevard, and here, now stood the new Amberson Mansion which was the pride of the town.

– Orson Welles’s narration for his Campbell Playhouse production

Welles’s 1939 radio production quickly establishes the neighbourhood surrounding the Amberson Mansion as the Amberson Addition. That name, taken from the novel, is first mentioned in the 131-minute version of the film by Major Amberson when he speaks to Aunt Fanny on the mansion porch in 1910. The RKO version only mentions the Amberson Addition during George’s ‘last walk home’.

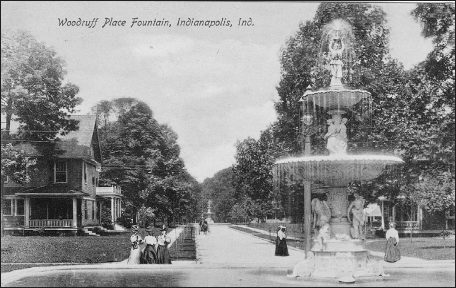

As of 1890, the dominant form of dwelling across all social classes in Indianapolis was the single family house.41 The wealthiest of Indianapolis lived in Woodruff Place, an early suburb established a mile and a half from the city centre, a proto-gated community and the widely acknowledged inspiration for Tarkington’s Amberson Addition. The Amberson Mansion itself was said to be inspired by the Knights of Columbus Headquarters on Delaware Street.42

A postcard representing Woodruff Place in the early twentieth century

The planning and construction of Woodruff Place was a typical Midwestern development in America’s Gilded Age, the parcelling of urban space into pockets of socio-economic distinction. In that significant year of 1873, James O. Woodruff bought eighty acres east of the city centre to create a park neighbourhood for the well-to-do. Woodruff’s prosperity was short-lived and the development of his suburban enclave was slowed by his bankruptcy. He died outside Indianapolis in 1879, aged only thirty-nine.43 The plan of Woodruff Place ostentatiously insisted on its residents’ wealth and status by the installation of fountains and statuary (which were quickly vandalised). Its boulevards were thirty feet wider than the streets of some of Indianapolis’s contemporary middle-class suburbs. Woodruff Place’s founding covenant established its exclusivity and aloofness from the rest of the city: fenced-off, its private streets and alleys, to be maintained by the owners of the houses, would not permit use by non-residents. It was said to have forbidden cows and chickens.44

Woodruff Place kept its political independence from Indianapolis while contracting its municipal services. It was not incorporated into the city itself until 1962.45 Its population grew from twenty inhabitants in 1880 to almost five hundred at the turn of the century. There were no streetcars to or from the Indianapolis city centre, but the wealthy inhabitants of Woodruff Place could probably afford private carriages.46 Tarkington’s novel does not locate a streetcar line outside the Amberson Mansion; by including one in the cinematic Amberson Addition, Welles was able to compress the diverse activities of the city to a manageable zone.

Woodruff’s exclusive zone of pretentious splendour was short-lived. In the twentieth century many of the stately homes were transformed into apartment houses.47 Tarkington’s Amberson Addition accurately anticipated this decline.

In the film, following Jack Amberson’s departure by rail to Washington in search of a consulship, George walks home to spend his final night at the Amberson Mansion. On the way he confronts the much-changed Indianapolis of 1911 as if for the first time. For the first time in his career, Welles was able to realise the subjective camera technique he had planned for the entirety of Heart of Darkness. The shooting script has the camera following George as he walks up a street “until it is so close that his body creates a dark screen for a DISSOLVE” to a new shot in which the camera “is now George”. The 131-minute version as assembled did not include that dissolve but instead transitioned from the railway station immediately to George’s point of view in the street.

Welles’s narration in this sequence is very carefully adapted from two different sections of Tarkington’s novel. It explains George’s alienation from modern Indianapolis:

George Amberson Minafer walked homeward slowly through what seemed to be the strange streets of a strange city; for the town was growing and changing as it had never grown and changed before. It was heaving up in the middle incredibly; it was spreading incredibly; and as it heaved and spread, it befouled itself and darkened its sky.48

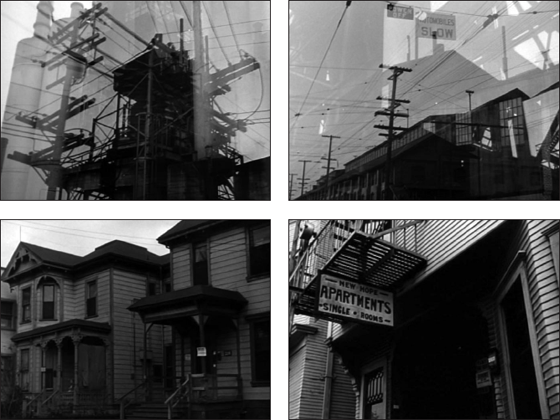

The narration was to have itemised a few of George’s childhood memories of the neighbourhood, closely adapted from the novel (this part of the narration was cut by Wise). The scripted images are also taken directly from the novel: shots of a ‘Stag hotel’, boarding houses, a dry cleaner, a funeral home, and a benevolent society (the novel reveals this to be the former house of George’s father’s family). This sequence was ultimately filmed from George’s point of view as a series of upwards-looking shots tracking along empty streets: the camera takes in telegraph wires, streetcar cables, grain elevators, an electrical generator, a factory, steel scaffolding, and grimy apartment houses.49 In the RKO version, the shots slowly dissolve into each other. Welles claimed he shot this sequence himself with a handheld camera in downtown Los Angeles, using found spaces rather than the drastically transformed locations he would use in later films.50

In Tarkington’s novel, George’s moment of urban alienation comes as a negative reaction to the racial diversity of the city. Welles’s adaptation is delicate. He took the sentence on the “befouled” city from chapter 28, which is not actually from George’s point of view at all, but occurs during George and Isabel’s long absence abroad. Tarkington immediately follows the passage with the observation:

Los Angeles doubling as Indianapolis

But the great change was in the citizenry itself. What was left of the patriotic old-stock generation that had fought the Civil War, and subsequently controlled politics, had become venerable and was little heeded. The descendants of the pioneers and early settlers were merging into the new crowd, becoming part of it, little to be distinguished from it. What happened to Boston and to Broadway happened in degree to the Midland city; the old stock became less and less typical, and of the grown people who called the place home, less than a third had been born in it. There was a German quarter; there was a Jewish quarter; there was a negro quarter – square miles of it – called ‘Bucktown’; there were many Irish neighbourhoods; and there were large settlements of Italians, and of Hungarians, and of Rumanians, and of Servians and other Balkan peoples. But not the emigrants, themselves, were the almost dominant type on the streets downtown. That type was the emigrant’s prosperous offspring: descendant of the emigrations of the Seventies and Eighties and Nineties, those great folk-journeyings in search not so directly of freedom and democracy as of more money for the same labour. A new Midlander – in fact, a new American – was beginning dimly to emerge.51

And in chapter 31, the actual scene of the ‘last walk home’, from which Welles took the line about the “strange streets of a strange city”, the strangeness is actually related to the faces George encounters among the “begrimed crowds of hurrying strangers”:

Great numbers of the faces were even of a kind he did not remember ever to have seen; they were partly like the old type that his boyhood knew, and partly like types he knew abroad. German eyes with American wrinkles at their corners; he saw Irish eyes and Neapolitan eyes, Roman eyes, Tuscan eyes, eyes of Lombardy, of Savoy, Hungarian eyes, Balkan eyes, Scandinavian eyes – all with a queer American look in them. He saw Jews who had been German Jews, Jews who had been Russian Jews, Jews who had been Polish Jews but were no longer German or Russian or Polish Jews. All the people were soiled by the smoke-mist through which they hurried, under the heavy sky that hung close upon the new skyscrapers; and nearly all seemed harried by something impending…52

Next, from Welles’s narration, again closely adapted from the novel: “this was the last walk home [George] was ever to take up National Avenue to Amberson Addition and the big old house at the foot of Amberson Boulevard”. In the script – but not the 131-minute version – the boulevard has already been renamed 10th Street. In the novel the stone pillars that marked the entrance to the Amberson Addition have vanished, although a fountain of Neptune remains. Welles’s narrator:

The city had rolled over his heart and buried it under as it rolled over the Major’s and the Ambersons’ and buried them under to the last vestige. Tonight would be the last night that he and Fanny were to spend in the house which the Major had forgotten to deed to Isabel. Tomorrow they were to ‘move out’.

Welles’s plan was to continue with another subjective tracking shot that moved through the interior of the Amberson Mansion. It was shot but not included in the 131-minute version, which cuts from the walk home to George kneeling before Isabel’s bed. The following narration, cut from RKO’s version and closely adapted from Tarkington, accompanied that shot in his mother’s bedroom:

The very space in which tonight was still Isabel’s room would be cut into new shapes by new walls and floors and ceilings. And if space itself can be haunted as memory is haunted, then it may be that some impressionable, overworked woman in a ‘kitchenette’, after turning out the light, will seem to see a young man kneeling in the darkness, with arms outstretched through the wall, clutching at the covers of a shadowy bed. It may seem to her that she hears the faint cry, over and over, of George crying, “Mother, forgive me! God, forgive me!”

This is a powerful projection into the city’s future working-class space. Welles’s narrator now announces that George had received his “come-upance”, “three times filled and running over. But those who had so longed for it were not there to see it, and they never knew it. Those who were still living had forgotten all about it and all about him.”53

The reshaping of the spaces of the modern city provided new opportunities for interaction between the classes, and this found expression in literature. Charles Baudelaire’s prose poem ‘Eyes of the Poor’ (from Paris Spleen, published posthumously in 1868) focuses on a wealthy couple in a luxurious new café who differ profoundly in their reactions to a poor family looking through the window. Marshall Berman wrote of how Baudelaire announced that Baron Haussmann’s Paris boulevards had “opened up the whole of the city, for the first time in its history, to all its inhabitants”; the city had become “a unified physical and human space”.54

George’s alienating encounter with the Indianapolis of 1911, as it was presented in Tarkington’s novel, is one such confrontation with the open modern city; George, with the probable sympathy of the author, reacts like Baudelaire’s snob, who wishes the poor to disappear from her sight. Welles’s adaptation of the ‘last walk home’ in the 131-minute version delivers the same alienating effect on George – for the better, it turns out, because it shocks him into admitting the irrevocable mistake of his treatment of his mother and Eugene. He attempts to redeem himself by working to support Aunt Fanny. But in Welles’s version George’s alienation is a reaction to the grim material condition of the empty cityscape rather than to the crowd. The narrator’s projection of some future “impressionable, overworked woman in a ‘kitchenette’” where there was once Isabel’s bedroom is another abstraction of the poor. In Welles’s script George had a brief encounter outside the mansion with some apparently well-to-do “riff-raff” in an automobile; by the time of the 131-minute version, George’s experience of urban alienation is stripped entirely of human interaction. The streets are eerily empty. The subjective point of view of the camera only makes the Indianapolis inner city appear more of an abandoned wasteland.

It’s a big change from Tarkington’s description of George moving through “thunderous streets” and “begrimed crowds of hurrying strangers”, but a necessary one for Welles to avoid carrying over the sympathetically presented racism of the original scene. But that moment in Tarkington’s novel was typical of the widespread bigotry of contemporary Indianapolis. Once a nexus of immigration, the proportion of foreign-born residents had declined to only nine per cent by 1910.55 City life was persistently segregated, particularly in the 1920s. Soon after the publication of The Magnificent Ambersons, Indiana would claim the largest Ku Klux Klan organisation in the country – an estimated 300,000 members at its peak in the early 1920s. The Klan dominated the city’s municipal election of 1925, and one of its members, Edward L. Jackson, ruled as a corrupt state governor from 1925 to 1929.56

Orson Welles’s solution as an adaptor was to be modest rather than critical: he simply eliminated the racism that was a key part of Tarkington’s provincial myth of decline. But Welles’s political radicalism was only beginning to stir and seek expression in film. Just days after recording his tender Ambersons narration, his lament for an idealised middle-class Eden, Welles was in Rio de Janeiro improvising a Technicolor documentary film about the city’s Carnaval. In Portuguese Welles found the word that best defined his sweet ache for the imagined past – saudade. ‘Carnaval’ quickly developed into a radical celebratory project that attempted to directly interrogate the racial politics of urban space and present a utopian vision of joyous racial mixing in the streets of a modern city.

NOTES