Aside from Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, most of Welles’s creative energies in Hollywood were devoted to contemporary political films about the American hemisphere. He attempted to interrogate the threat of fascism in a string of projects dating from 1939. Most never reached production.

Recurrent and politically significant settings of the Pan-American film projects include urban political frontiers (port cities and the border town) and the impoverished urban periphery (the shantytown). These are spaces of authoritarian control and social exclusion where fascist manoeuvers frequently burst to the surface. Welles would consistently develop experimental techniques to illustrate such manoeuvers.

Later in the 1940s, a number of Hollywood directors would pursue synoptic overviews of urban space, often in films shot on location on the theme of police investigation and surveillance, such as The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948) and Side Street (Anthony Mann, 1950).1 Earlier in the decade, and through his perspective of anti-fascism, Welles had frequently pursued comprehensive visions of the total city. In this pursuit he attempted to synthesise the ambitions of the international ‘city symphony’ cycle of the silent era with Hollywood narrative filmmaking of the 1940s. He experimented with long and mobile shots that would track ambulatory characters, vehicles, and ritual human and animal processions through diverse passages of urban space. He conceived ambient sound schemes, planned intercutting between contrasting social spaces, and the integration of synoptic maps and architectural models into the mise-en-scène. In his early years at RKO (1939–1942) he had access to expensive studio sets, miniatures, matte paintings, and optical printing. As he shifted from studio-based to location-based filmmaking, Welles sketched and was sometimes able to implement innovative methods of transforming found urban spaces into cinematic spaces that expressed his ideological and personal vision. This programme reached its zenith in Touch of Evil, when he converted Venice Beach in Los Angeles into his fictional Texan-Mexican border town, ‘Los Robles’.

* * *

Welles’s first feature project under contract to RKO was an experimental and Americanised anti-fascist adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It was never produced, despite extensive scripting and pre-production planning. Following Kane and Ambersons, he shot but was unable to finish It’s All True, a celebratory semi-documentary anthology intended as an emissary for President Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy. Although Welles rather dubiously disavowed any particular fondness for the thriller genre – “I can pretend no special interest or aptitude”2 – the rest of his anti-fascist Pan-American film projects fall into that genre.

The Mercury production of Eric Ambler’s 1940 novel Journey into Fear was the first of these spy thrillers to reach cinemas, under Welles’s (partial) supervision. Of the other many Pan-American thrillers Welles developed at least until the end of the 1970s, only The Stranger (1946), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), and Touch of Evil were actually finished and released, and all three were travesties of the director’s editorial wishes. These three were later categorised as film noirs. Welles’s Pan-American and anti-fascist emphases in these three films were frequently blunted by studio interference. As the earlier, more Wellesian versions of these three films no longer exist (or were never finished), scholars have long found it fruitful to examine evidence of the director’s original conceptions in production documents. In fact, the long-term Pan-American strain of Welles’s oeuvre can only be comprehensively appraised with recourse to such scripts, treatments, correspondence, and pre-production art for both his produced and his unmade films. These documents contain sketches for innovative approaches to creating cinematic cities that did not find fruition in any of the commercially released films. Welles accrued masses of written texts during the sometimes permanent pre-production stage of a project. The surviving documents are, however, often fragmentary and occasionally of ambiguous authorship. In the early to mid-1940s, Welles commissioned writers such as Norman Foster, Paul Trivers, John Fante, Paul Elliot, Brainerd Duffield, Fletcher Markle, Les White and Bud Pearson to draft treatments and screenplays which would be the rough material for Welles’s rewrites and final revisions (as he had used Herman J. Mankiewicz’s preliminary drafts in the writing process of Citizen Kane).3 He had managed to stamp his personality on a vast turnover of weekly radio dramas by the same method. But these collaborations complicate Welles’s auteur status and demand a careful appraisal of the many surviving documents, which range from Welles’s own meticulously detailed and industry-standard ‘Revised Estimating Script’ for Heart of Darkness (“I did a very elaborate preparation for that, such as I’ve never done again – never could”4) to an uncredited, incomplete, hand-annotated draft adaptation of Michael Fessier’s novel Fully Dressed and In His Right Mind (1934). There are also drafts annotated with studio censorship guidelines, storyboards, and other types of production artwork.

The best approach is to contextualise these pre-production documents, by Welles’s own definition totally provisional, as best as possible within the known details of his creative process. From early on Welles showed no particular loyalty to conventional industry-standard screenplay formats and much interest in expanding the definition of screenwriting as a practice. During the making of the ‘Carnaval’ segment of It’s All True in 1942, he explained to RKO that he considered the ‘minutes’ of his detailed nightly discussions with research collaborators “the nearest thing we have to a script”. These minutes recorded the fruitful debates within the collaborative creative process, provided a clarifying recap of the segment’s thematic and structural evolution, and determined the logistical approach to realising new ideas on film, even if they were not comprehensible to everyone; the minutes “can mean little to anybody except ourselves”, stated Welles.5

* * *

Welles had already performed Heart of Darkness in a radio script by Howard Koch in 1938. For his own screenplay, he altered Conrad’s late nineteenth-century Congo setting to a contemporary unnamed ‘dark country’.6 Welles declared, “The film is frankly an attack on the Nazi system.”7 He intended to play both the American narrator, Marlow, and the object of his search in the jungle, the insane ivory agent Kurtz. In preparation Welles commissioned a comprehensive study of tribal anthropology,8 similar to the exhaustive research into Brazilian culture he would gather while making It’s All True.

Welles’s ‘Revised Estimating Script’ of Heart of Darkness is dated 30 November 1939, less than three months after Great Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. Following an introduction to the film’s unprecedented technique – a first-person method that will present the action almost entirely through the eyes, ears, and inner monologue of Marlow – the action proper begins in New York Harbor, a port setting that will turn up again in drafts of The Smiler with the Knife, Don’t Catch Me, The Lady from Shanghai, and The Cradle Will Rock. The city appears in long shot, “seen from the East River just at dusk”, followed by a “SERIES OF DISSOLVES showing the movement of traffic on the river”.9 We see Manhattan from afar against the sunset sky. Marlow narrates, “Further west – on the upper reaches – the place of the monstrous town marked ominously on the sky, a brooding gloom in the sunshine, a lurid glare under the stars.”10 Then we see a series of ‘lap dissolves’ to various places in the city at the very moment its lights illuminate: bridges over the Hudson and East Rivers, parkways, boulevards, and skyscrapers.

In his first Hollywood script, Welles brings his extensive radio experience to the task of attempting to revolutionise cinema sound. He makes notes for a now commonplace ambient use of fragmentary diegetic sound sources to help convey the city’s spatial distinctions:

As we move down the length of the Island, snatches of sound and music, the beginnings of life of the city at night, are heard on the sound track. In Central Park, snatches of jazz music is heard from the radios in the moving taxicabs. The sweet dinner music in the restaurants of the big hotels further West. The throb of tom-toms foreshadow the jungle music of the story to come. The lament of brasses, the gala noodling of big orchestras tuning up in concert halls and opera houses, and finally as the camera finds its way downtown below Broadway, the music freezes into an expression of the empty shopping district of the deserted Battery – the mournful muted clangor of the bell buoys out at sea, and the hoot of shipping.11

Welles would sketch versions of this sound scheme for different projects throughout the years – most notably to accompany Touch of Evil’s long opening tracking shot through Los Robles – but he was consistently thwarted.12 Despite his innovations on Kane and Ambersons in collaboration with RKO sound editor James G. Stewart, Welles was frequently constrained in experimenting with sound in Hollywood.

This plan for the beginning of the film suggests a miniature city symphony that emphasises New York as a port city. Its “sleepless river” leads to “the mystery of an unknown earth. The dreams of men, the seeds of commonwealths, the germ of Empires.”13 Marlow leans against the single mast of a ship in the harbour and narrates how New York, the towering modern city, was once “one of the dark places on the earth … they must have been dying here like flies four hundred years ago.” His narration then closely follows Conrad: “It’s not a pretty thing when you look into it too much, the conquest of the earth which mostly means the taking it away [sic] from those who have a different complexion or slightly different shaped noses than ourselves.”14

There is a flashback to another harbour in “some Central European seaport town”.15 These are the first two instances of a dramatically pregnant and cosmopolitan setting that frequently occurs in Welles’s films: the international seaport where characters of diverse and ambiguous backgrounds intermingle and scheme. Welles would use seaport settings in Journey into Fear (Istanbul and Batumi), The Stranger (a Buenos Aires-like port in South America), The Lady from Shanghai (New York, San Francisco, and Acapulco), Mr. Arkadin (Naples, Cannes, Juan-les-Pins, Tangier, and Acapulco), The Immortal Story (Macau), and the unproduced late 1960s script Santo Spirito (a fictional island in the Caribbean).16

Marlow the sailor is “used to clearing out for any port in the world with less thought than most men give to crossing a street”.17 Parts of this Central European seaport were intended to be created with miniatures by RKO’s special effects department. Welles inserts a note to special effects artist Vern Walker: “when making long shots of harbor and settlement from the miniature, suggest the following to give movement in the shots: a dredge working near the railroad track, dynamite explosions with accompanying dust and smoke, etc.”18 At the beginning of the seaport town sequence Marlow looks at a map of the “dark country” through a shop window. “I’ve always had a passion for maps,” he narrates. “When I was a child there were many blank spaces on the earth, and when I saw one that looked inviting – I’d put my finger on it and say, ‘When I grow up I’ll go there.’”19 Maps were frequently interpolated into Welles’s mise-en-scène in this period as one way of providing an economical geographical synopsis. They would be used in Citizen Kane, the pre-release cuts of Journey into Fear, and the script for The Smiler with the Knife. At a later stage in Heart of Darkness Kurtz’s fiancée, Elsa, draws a map of the dark country’s river.

When Marlow accepts the job to find Kurtz, the script enters the jungle and ceases to concern city culture. Welles’s projected budget of more than a million dollars, twice the target amount for Welles’s first film, made the experimental film unworkable for RKO.20

* * *

Early on Welles was attracted to the contemporary anti-fascist incarnation of the spy novel epitomised by the work of English writers Graham Greene and Eric Ambler. Cultural historian Michael Denning calls this new type of spy novel the ‘serious thriller’, although that does not necessarily imply grimness of execution in the age of Hitler and Mussolini. In fact, the novels are wildly entertaining. Aside from the considerable literary qualities of Ambler’s and Greene’s work, the ‘serious thriller’ surely appealed to Welles because it abandoned the genre’s traditionally conservative political orientation to embrace the cause of the Popular Front.21

Welles would eventually come to adapt Ambler and, much later, Greene. To Denning, the archetypal narrative of the Ambler–Greene ‘serious thriller’ novel is as follows:

An educated, middle-class man (a journalist, teacher, engineer) travelling for business or pleasure on the Continent … accidentally gets caught up in a low and sinister game (no longer the Great Game) of spies, informers, and thugs. He is innocent both in the sense of not being guilty, and in the sense of being naive. He is an amateur spy, but not the sort of enthusiastic and willing amateur that [John Buchan’s Richard Hannay] is; rather he is an incompetent and inexperienced amateur in a world of professionals.22

In novels of the 1930s Ambler and Greene present a European milieu of spies, criminals, lowlifes, and refugees whose ethnic and national identities have been obscured by the political disruptions of World War I. The stories are frequently set in cosmopolitan crossroads in upheaval following the end of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires or in transit between such cities by railway (Greene’s Stamboul Train, 1932), by ship (Ambler’s Journey into Fear), or by foot (Ambler’s Cause for Alarm, 1938).23

Welles was ideologically opposed to political borders and the fictions of nationalism (he was loyal to more antiquated, romantic, and inclusive cultural identifications). His strong antipathy to police, government bureaucracies, borders, and passports would be expressed in his British television documentaries several times in the mid-1950s. He found a kindred thinker in Ambler, whose novels frequently focus on hapless but sympathetic characters rendered stateless by the vicissitudes of war and occupation, or on the difficulties, anxieties, and sometimes arbitrary violence of bureaucratic control over human passage across political frontiers.24

In a 1975 conversation, Ambler recalled:

[C]ertainly to anyone who came to maturity during the Fascist years the importance of papers became overwhelming. People are denied passports – that means now the right to travel freely – for often, it seems to me, illogical reasons. […] it’s a question of control to deny him freedom of movement. […] diplomatic documents, papers and such have become a 20th century means of control, and I make use of them in my work.25

In the cinema the new category of European spy novel found an analogue in Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich (1940) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940). Although Welles was critical of Hitchcock’s later work, at least in posthumously published private conversations, his early thrillers are firmly in the tradition of Hitchcock’s early work.

Welles prepared two anti-fascist novels by Popular Front novelists as prospective projects at RKO: The Smiler with a Knife, by Cecil Day-Lewis (writing as Nicholas Blake, 1939), and The Way to Santiago, by Arthur Calder-Marshall (1940). Along with the later adaptation of Richard Powell’s Don’t Catch Me (1943), they make for a progressively sophisticated and entertaining trilogy of Hitchcockian thrillers. Welles did not restrain himself to realism but exploited the genre for its theatrical, carnivalesque, and comic potential. No script in this Hitchcockian trilogy was produced.

* * *

An unsigned memo, probably written by Welles (or possibly by John Houseman), makes a self-critical summary of an early draft of The Smiler with the Knife and gives insight into the creative process of adaptation. The memo confesses that one scene, written in haste, contains “just whatever I could get down on paper”.26 Such a provisional quality – rough assemblies of scenes, gestures towards structure – must be assumed of many other Welles scripts. What seems to be the latest draft, the 178 page “Revised Estimating Script”, is dated 9 January 1940, and bears no writer credit. Welles seems to have created about half the script’s plot and taken the rest from the source novel.27 Despite its anti-fascist orientation, this draft’s politics are not nuanced. The fascists are cartoon villains and the script is plagued by implausibilities. The dialogue is in the vein of the sometimes inscrutable banter that would characterise Welles’s later original scripts The Other Side of the Wind and The Big Brass Ring. There is a note that a “March of Time sequence”, a fictional newsreel, will be interpolated into the script as an expositional device. The idea would be revived for Kane.

The action of Smiler commences at a wedding ceremony at the remote country house of a parson. The far-fetched MacGuffin is a locket in the beak of a crow. Two strange men separately chase the crow to the parson’s house, but newlyweds Johnny and Gloria evade surrendering the locket, which is engraved ‘S.S.’ and contains a vintage photograph of an old woman.

The couple take the mysterious find to Johnny’s father, John Strangeways Sr, the head of the US Department of Justice in Washington, DC. He connects it to a secret fascist organisation about which nothing is known but its name: ‘S.S.’ stands for ‘Stars and Stripes’. Strangeways makes a speech for democracy. The politically indifferent Johnny wants to know what his father is yammering on about. The answer? “Shirts. I like to pick my own color. I like to go on a ballot with more than one name. Get it?”28 Strangeways lectures the newlyweds on similar international fascist conspiracies, such as the recent action by the Cagoulards against the French Third Republic. He worries about the USA because “one seventh of the munitions manufactured in this country can’t be accounted for. We don’t know how big this is, but we can guess. And the worst of it is we haven’t an idea in the world who’s behind it.” When Johnny protests, “The American people will never stand for a dictator,” his father rejoins: “You mean they’ll never give a politician that much power. How about a hero? We like heroes over here and this one won’t talk like a dictator. He’ll look like a movie star and everybody’ll love him.”29

Shortly after, an aviator hero in the mould of Nazi sympathiser Charles Lindbergh lands his ‘stratosphere’ machine in Washington, DC, in an atmosphere of public ecstasy. The hero’s name is Anthony Chilton and he would surely have been played by Welles. He is feted on the radio by “militant Broadway columnist” and democracy defender Wally Winters (a barely disguised Walter Winchell).

The newlyweds meet Chilton at a party where the guests play games. Chilton dresses in drag and, in one of the script’s heavier demands on the audience, will be recognised as a dead ringer for the woman in the locket photograph – his female ancestor. Chilton tries to romance Gloria, who quarrels with her husband; the newlyweds separate for the rest of the film. The structural conceit of separated newlyweds would be repeatedly revisited in Welles’s thriller scripts, although it made the screen only once, in Touch of Evil.30

Gloria accompanies Chilton to Rosa’s restaurant, “a rather sinister establishment outside the city limits of Washington” (the script suggests as a model Ernie Byfield’s Pump Room at the Ambassador East in Chicago).31 This is the beginning of an extra-marital romance, although the political intrigue builds. The urban settings are briefly swapped for rural Kentucky, where Chilton owns a country house. There Gloria discovers Chilton to be the head of Stars and Stripes. He mobilises his organisation to capture her in a dash across the United States. In one car chase sequence through the country the visual action occurs off screen: a contrast between static shots and “wild screeching of police sirens in a constantly building pattern of sound. Big chase music.”32 The script comes most alive during a chase sequence in a crowded urban shopping street in Zenith, Pennsylvania. Gloria escapes capture by the very Hitchcockian solution of dressing as Santa Claus.

Welles incorporates maps in a moment of Hitchcockian hokum. Gloria realises the miniature golf course on Chilton’s country property in Kentucky really represents a secret map of the United States indicating the fascist organisation’s “twenty-six secret arsenals and munitions dumps”. She annotates a map of the United States in an atlas with the locations – and “the resemblance of the map to the miniature golf course is striking enough to make the idea clear”.33 Chilton has also hidden secret papers inside a terrestrial globe. She sends it all to Strangeways in Washington.

Although the action skips from the nation’s capital to the rural south, to Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio, to Zenith and even to the Welles’s alma mater, the Todd School for Boys (which was in Woodstock, Illinois), the urban settings would have been filmed in the studio using sets and process shots. The street scenes of Zenith would have been created on the RKO Ranch.34 It’s a challenge to imagine how Welles would have overcome the generic quality of the urban settings based on this draft of the script. In other ways The Smiler with the Knife would have needed substantial reworking to rise above this draft’s weaknesses and implausibilities. Welles would continue to marry serious and urgent political themes to screwball comedy and the carnivalesque, but this early exploration of a fascist conspiracy is not at all sophisticated. Welles abandoned the project and made Citizen Kane.

* * *

A superior stab at the fascist-infiltration suspense plot is Welles’s adaptation of Calder-Marshall’s The Way to Santiago. The title of the film adaptation never graduated beyond the working titles Mexican Melodrama or Orson Welles #4. What seems to be the latest draft, a ‘Third Revised Continuity’ script, is dated 25 March 1941, just over a month before the premiere of Kane. The practical purposes of this version of the script should not be overlooked: marked ‘For Budgeting Purposes Only’, it was also the version submitted to Mexican authorities for official approval to film on location in the country (which was granted). That said, this draft seems to represent an advanced state of development. James Naremore persuasively argues for Mexican Melodrama as a reworking of Heart of Darkness within a more commercial, less experimental form.35

Welles doesn’t seem to have planned to direct the project, although he would have starred in the lead role. With this project Welles moved away from the USA as a setting. The script is prefaced by the declaration that Mexico “shares with us the American dream of freedom”.36 Under President Lázaro Cárdenas, Mexico had nationalised its oil in 1938, expropriating the assets of international firms. President Roosevelt maintained a pacific stance against retaliatory intervention in line with the Good Neighbor Policy.

The Way to Santiago explored the fascist threat to Mexico in the period. One innovation in Welles’s script is its usual first-person subjectivity, which is distinct from the near-total observance of Marlow’s point of view in Heart of Darkness. The lead character – named ‘Me’ – wakes up naked in an anonymous empty room surrounded by representatives of “every race in the world, every color”. Me has no documents and does not remember who he is. The amnesia motif would be used in several future Welles films, including Mr. Arkadin, although in this story the condition is genuine.

Me is helped by a newspaper man named alternately Gonzalez or Johnson; the draft is evidently an indecisive composite of versions. They are in Mexico City, and Gonzalez/Johnson mysteriously offers to take Me to a party at the presidential palace to “get friendly with the most beautiful girl in the world”. Me’s presence makes a shocking impression on the guests, including the beauty, Elena. She identifies him as Lindsay Keller, a fascist connected with a Mexican revolutionary group, led by one General Torres. Gonzalez/Johnson’s stunt at the palace is designed to pry further information from the General about his fascist plot to take over Mexico. Torre’s organisation has stockpiled ammunitions and set up a radio station on the island of Santiago. We later discover Keller is the charismatic fascist radio personality ‘Mr England’, who has been brought to the Americas to propagandise to the “hundred and thirty million people [who] speak English in this hemisphere”. Mr England was based on the English Nazi broadcaster William Joyce (aka Lord Haw Haw).37

Me and Gonzalez/Johnson leave the presidential palace and walk into the city’s zócalo, its enormous central square. The mob scene as sketched promises grand spectacle and threatening overtones: thousands of patriots enjoying the Mexican Independence Day ritual of the presidential grito, a cry of “Viva Mexico! Viva la República! Viva la Revolución!” There is “a hurricane of voices – a typhoon of confetti – and finally, fireworks”.38 In a particularly Hitchcockian moment, Gonzalez/Johnson is shot as the fireworks explode; the bullet was surely intended for Me. The police allow Me to leave, but the “unanimously sinister” crowd suspects Me’s guilt.39 The ecstasy of the patriotic mob turns threatening. Me briefly hides among a busload of gauche American tourists.

Me meets Elena at the city’s El Chango, a nightclub featuring flamenco entertainers in exile from Spain. Me learns that Elena is not part of Torres’s conspiracy, but instead a Mexican spy. The amnesia has left Me with total naivety about fascism itself, so Elena provides him (and the audience) a definition: “It means tyranny. It means everything that isn’t human or beautiful. It means the ant hill, darkness, and death.”40 Me accepts her definition and confesses, “I can’t remember what I liked about it. I guess fascism is something that happens to you – like disease. I guess everybody is born innocent. Well, I was born this afternoon.”41

And so Me and Elena conspire to destroy the fascists’ munitions dump in Santiago. Me makes a long and dangerous journey out of the teeming capital city to Santiago, with a side adventure in a remote jungle village saloon, where since the oil nationalisation, “business is so bad nobody’s drinking”.42 Further along Me meets the real Keller (his physical double) and is captured.

Later the cadre of conspirators sit on the sundeck of General Torres’s yacht and rather didactically share their theories of fascist rule. A Spanish aristocrat states: “the lesson we learned from Spain was that a military minority with the help of foreign sympathizers and the principal of non-intervention can overthrow a government which had strong support at home and institute a military dictatorship in its place.”43

The real Keller adds:

The terrorist provocation must break out simultaneously all through the country so that the public will be stunned and bewildered. They’ll realize that only a strong man with dictatorial powers can save them. … Mexico at last a country where the rich can live in security.44

But Me’s voice interrupts from a loudspeaker. He has escaped and infiltrated the radio station in Santiago to broadcast a passionate anti-fascist message, “another Grito”, which we see reach listeners across the Americas. Me participates in capturing General Torres, but Mr England drowns trying to reach a submerging German submarine.

Unlike The Smiler with the Knife, the Way to Santiago project was to have been shot extensively on location. Despite some initial resistance from the Mexican government,45 pre-production was underway in Mexico in the second half of 1941. RKO editor Jose Noriega, representing Mercury Productions in Mexico City, successfully negotiated with the Secretary of State for the authorisation to make two films in the country: ‘My Friend Bonito’ and the Way to Santiago project. Although Welles had yet to sign up to officially represent the Good Neighbor Policy in Latin America, Noriega was already arguing that Santiago would “enhance the better ethical and social values of Mexico by the light of the policy of Continental and democratic solidarity that Mexico is pursuing”.46 Authorisation was granted and both scripts were approved with the proviso of the presence of an on-set representative from Mexico’s Department of Cinematographic Supervision – in other words, a censor.47

Around the same time a tentative shooting schedule and detailed budget were drawn up for Santiago, presumably by Noriega. A month of location work would begin in April 1942, followed by inexpensive Mexico City studio filming. Noriega essays the possibilities of location filming in the capital itself. El Patio bar, supposedly the inspiration for El Chango, would either be used as found or reconstructed on a stage; a custom-made neon sign would have to be fitted to the exterior. Perry Ferguson, the art director for Kane, seems to have been already lined up. No director was yet locked in, but it is noted that “a man like [Norman] Foster” should be paid about $15,000. Mexico’s eminent Gabriel Figueroa was pitched as cinematographer.48

In September Welles visited the Yucatán to scout locations for the Santiago project; 16mm footage, possibly shot by Welles himself, has survived from this expedition.49 That same month Norman Foster began shooting ‘My Friend Bonito’ on location with ‘co-director’ status. Foster was also probably set to direct the Santiago project the following year, but Welles’s plans had to be changed after the attack on Pearl Harbor. On 10 December, between takes of The Magnificent Ambersons, Welles wrote to Foster in Tlaxcala about ‘Bonito’: “On the phone tonight I’m going to try to tell you how really and truly beautiful and important is the picture you’re making [but also that] war has broken out and I have broken down.”50

Foster was withdrawn from Mexico to direct the Welles-Cotten script of Journey into Fear, allowing Welles to wind up his Hollywood commitments faster. In early February Welles went to South America to make the Brazilian portions of It’s All True, now officially under the umbrella of the Good Neighbor Policy.

Around the same time this draft of the Way to Santiago project was completed, in early 1941, Welles showed interest in another Mexican-set anti-fascist screenplay, by Paul Trivers, with the working title Unnamed Mexican Story. The story involves striking labourers on a Mexican ranch who battle a military force employed by the cruel ranch owner. It is difficult to ascertain the extent of Welles’s involvement in this strongly Marxist screenplay’s development.51

* * *

Welles’s departure from RKO following It’s All True did not put an end to his work in the thriller genre. In fact, the most enjoyable of his early unmade antifascist screenplays, and the third of his Hitchcockian trilogy, is Don’t Catch Me, “a farce melodrama” based on a 1943 novel by Richard Powell that had been serialised in American Magazine. A press release was drafted by Mercury Productions in April 1944 to announce imminent production and that Welles would write the final shooting script.52 The most realised version of the script is an undated 103-page draft that credits Welles alongside co-writers Bud Pearson and Les White.53 This time the story varies the device of a separated newlywed couple by allowing their joint adventure to prevent the consummation of their marriage.54

The script begins with an evocative night scene as a German submarine dispatches Nazis in rubber rafts to New York City. By the next morning the Nazi agents are dispersing into the United States via Penn Station, where their conspiracy intersects with the reunion of the soon-to-be-married Arab and Andy. Like Susan Alexander in Kane, Arab suffers a “coothache”.55 James Stewart would have been well cast as Andy, a hapless army lieutenant and antiques dealer. But except for the regularly employed New York Harbor and the scenes at Penn Station, Don’t Catch Me is mostly set around rural Long Island. The settings actually closely resemble those of Welles’s less cosmopolitan early drafts of The Lady from Shanghai.

Don’t Catch Me was promised but not delivered. In 1945 Welles announced a radio version starring his wife, Rita Hayworth, on the CBS show This Is My Best, but the show’s official director was unhappy with Welles’s choice – and possibly his conflict of interest as rights holder – and cancelled the promised broadcast.56

The scripts for Welles’s Hitchcockian trilogy, thematically unified around the threat of a fascist conspiracy, were prepared for very different approaches to creating urban space on screen: Hollywood studio re-creations in the case of The Smiler with the Knife, authentic Mexico City locations and studio work for the Way to Santiago project. It’s difficult to determine what approach Welles would have taken with Don’t Catch Me had he been able to progress with production.

* * *

The Mercury production of Eric Ambler’s Journey into Fear was exceptional among Welles’s early 1940s run of anti-fascist thrillers because its settings were not transferred to the Americas. It was also the only one of Welles’s thriller projects to be actually filmed and released to theatres during Welles’s stint at RKO, albeit in a much mutilated and censored form.

The embryonic scripts of Journey into Fear are more politically sophisticated than the shortened, watered-down version finally released to cinemas in 1943. They illustrate the challenges Welles faced as a political filmmaker during wartime, even within such a commercially orientated genre. The ‘Budget Script’, the next-to-last draft, is dated 1 August 1941 and was written by Welles and actor Joseph Cotten. Numerous blue replacement pages were inserted up until January, when a new final shooting script was typed for production. Norman Foster’s copy of this ‘Budget Script’ contains annotations in pink pencil from somebody at RKO to guide revisions that would satisfy both the moral censorship of the Production Code and the political sensitivities of the State Department now that the United States had entered World War II. Anti-fascism had obviously become the official stance all around, but many of Welles’s and Cotten’s nuances were stripped out at the outset.

The pre-censorship version of the ‘Budget Script’ (incorporating the blue pages) begins in a grimy Istanbul hotel. Banat, a silent assassin armed with a revolver, listens to a “very sentimental French song” on a skipping gramophone record – his aural signature. He wanders into the street and observes the arrival of an American couple at the Hotel Adler-Palace. The Americans are Howard Graham, a timid American ballistics expert on assignment to survey the armaments of the Turkish navy, and his wife, Stephanie. Kopeikin, the obsequious local representative of Graham’s firm, goes to great effort to pull Graham away from the comforts of a hot bath and dinner. Graham is uninterested in Kopeikin’s promise of “girlies” but is eventually dragged away from his wife.

At Le Jockey Cabaret, a cosmopolitan nightclub, Graham meets the beautiful Serbian singer Josette. During a magic act, the magician is shot by Banat. Kopeikin and Graham visit Colonel Haki, chief of the Turkish secret police, who reveals an assassination plot by a Nazi agent, Moeller, to delay the rearmament of the Turkish navy. Banat’s bullet was intended for Graham. Haki decides Graham will escape Turkey via a cargo ship (the Persephone) bound for Batumi in Soviet Georgia, and assures him that Mrs Graham will meet him at his destination. With Graham now out of the way, Haki will pursue the seduction of Mrs Graham, allowing her to believe her husband is involved with another woman.

Meanwhile, Graham is onboard the Persephone with Josette and her Basque manager, Gogo, as well as mysterious characters of various nationalities and political attitudes. Josette seems to propose an affair, although it is later revealed as more of a financial proposal administered by Gogo. Banat appears in the ship’s dining room and intimidates Graham. One of Haki’s secret agents, Kuvetli, is killed shortly after revealing his true identity to Graham. Haller, a polite German archaeologist, in turn reveals himself to be the Nazi Moeller. Graham is bundled off the boat in Batumi by Moeller and his henchmen, but he escapes and seeks his wife at the Grand Hotel. Alas, Moeller is already with Stephanie (and there are hints that Haki has made progress in his seduction of the woman). Graham winds up in a rooftop duel with Banat. Moeller is shot, Colonel Haki turns up for the shootout and is killed, and finally Banat slips to his death. Graham survives. The script ends incomplete, with a “TAG TO FOLLOW”.

The film was nominally directed by Norman Foster under the heavy pre-production guidance of Welles, who was a key supporting player as well as the film’s uncredited producer and co-writer with Joseph Cotten. Early scripting work was also contributed by Richard Collins and Ellis St. Joseph, but Cotten was assigned sole screenplay credit.57 Virtually every scene was carefully storyboarded in pre-production. The storyboards, which have survived, were very closely followed in execution by Foster, which is hardly surprising considering the short time he had to prepare for filming.58 For these reasons Journey into Fear is best considered an ensemble work of the Mercury company. Everett Sloan, who played Kopeikin, remembered that Welles directed his own scenes, and said, “I think it retains much of Orson’s original conception of the picture.”59

Joseph Breen, in between stints as Hollywood’s chief film censor, was in 1941–42 the general manager at RKO and effusive with praise for what he had seen of The Magnificent Ambersons.60 The annotations to Foster’s copy of the ‘Budget Script’ of Journey into Fear make clear that Breen had read the script and passed along his comments. The moral objections mainly concerned Josette and Graham’s proposed transactional adulterous affair. The censorship annotator also cautions against negative comments about Turks, who had signed a non-aggression pact with Germany in mid-1941. Colonel Haki’s casual mockery of “the American point of view” is pencilled out because it “presents Turks (and a ranking officer at that) without morals”.61 The character of Josette describes Turks as “heathen animals” who in the last war “killed babies with their bayonets” (“Mr. Breen cautions that not only censorship but our own State Department will strenuously object to this”62). The wide diversity of political opinions presented in dialogue onboard the cargo ship was to be stripped of controversy. The Basque Gogo is in favour of appeasing Germany as long as business can continue; this was objectionable because the film would be watched by “thousands in places (Latin America) where agreement with speeches could bring applause and even riot”.63 Gogo recalls he had taken no sides in the Spanish Civil War, either, but another passenger, Madame Mathews, shudders to imagine “if the Reds had won… They violated Nuns and murdered Priests.” RKO’s legal advice: “Church Legion of Decency positively will fight to the end on this … same thing State Dep’t … very delicate. Reds are our allies.”64 The political situation would be drastically reversed in Hollywood five years later.

A 102-minute version was previewed in Pasadena on 17 April 1942, in a double feature with the Charles Laughton comedy Tuttles of Tahiti. The comment cards ranged from high praise to total dismissal. A dialogue continuity has been preserved but the long version is lost.65

RKO amended this long cut to an unconventionally brief 71-minute version, which was previewed in August 1942 and has survived. Welles later remembered it as “the opposite of an action picture” but that RKO “just took out everything that made it interesting except the action”.66 Although estranged in other ways from RKO, Welles was allowed a short time to revise this cut in October 1942 for a 68-minute version that was commercially released the following year.67 Welles reframed the narrative to play via the point of view of Howard Graham (Cotten); Cotten voiced an amusing narration that comically emphasised Graham’s husbandly devotion. The changes demoted Stephanie (Ruth Warwick) to genial one-dimensionality; the restriction to Graham’s point of view meant eliminating the scene where Colonel Haki prepares to seduce Mrs Graham, and downplayed Welles’s separated couple motif. Welles filmed a new single-shot ending with Cotten that resurrected the dead Haki, who had only suffered a mere flesh wound. Welles also removed his producer and co-writer credits.

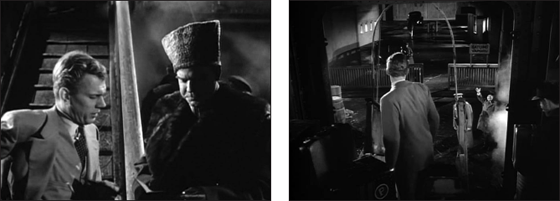

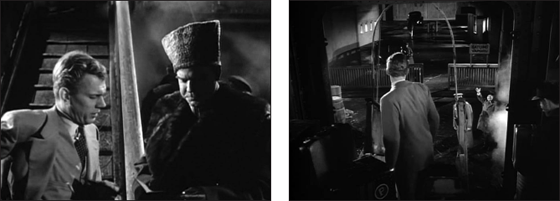

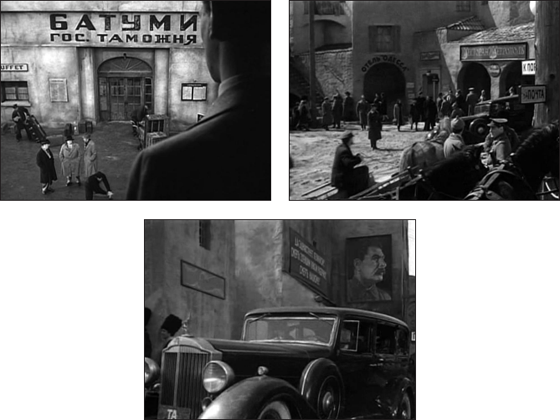

Journey into Fear remains an enjoyable orientalist spy fantasy that never takes its anti-fascist agenda too seriously. To be fair, this was true even before RKO’s censoring of the script. The opening page of Welles and Cotten’s ‘Budget Script’ insists: “The names ‘Athens’ and ‘Alexandria’ are used in this draft only for convenience. Pay no attention to geographic correctness.”68 That’s the general spirit; Ambler’s novel was written without the experience of visiting the Central Asian settings.69 The film was created almost entirely inside RKO Studios in the manner of Hollywood orientalist concoctions such as Algiers (John Cromwell, 1938), Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943), and the adaptations of Ambler’s novels Background to Danger (Raoul Walsh, 1943) and A Coffin for Dimitrios (as The Mask of Dimitrios, Jean Negulesco, 1944). In Journey into Fear, Istanbul is briefly glimpsed in exteriors by night as Banat (Jack Moss) stalks the Grahams outside their hotel; sandbags mounted alongside the street suggest wartime. At the city’s shadowy Bosphorus port Ambleresque anxieties play out when Colonel Haki takes Stephanie’s passport from Graham and establishes arbitrary control over the fate of the couple. At the end of the journey at the port of Batumi, a convincing neighbourhood in the Soviet city is created on the Hollywood backlot by signs in Cyrillic (although not in Georgian script) and large portraits of Joseph Stalin.

Joseph McBride has described Journey into Fear as “at best a very rough draft for some of Welles’s later films”.70 When Welles returned to the anti-fascist thriller in the mid-1940s, with the valuable experience of location work in South America, he would pursue new techniques of putting urban spaces on screen.

The port at Istanbul

The port at Batumi

NOTES