Orson Welles’s lifelong enthusiasm for the exotic was founded on a thoughtful and humanistic embrace of the foreign: languages, social rituals, food, music, and literature. Few other prominent Americans of the time gave such energy to the promotion of a cosmopolitan sensibility. To be cosmopolitan was to be inclusive, open-minded, committed to social justice, and orientated to an internationalist future. Nevertheless, many of Welles’s cosmopolitan enthusiasms were steeped in the same romantic nostalgia for pre-industrial society he had invested in the vanished America of Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. Welles continued to combine the political and the romantic within the same vision.

In the 1930s and 1940s his cosmopolitanism was instilled with moral seriousness and urgency. Fascism not only was destroying Europe but threatened the rest of the world. The OCIAA, implementing Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy, sought to improve relations across the Americas to ward off the influence of fascist Europe and to increase Pan-American economic and cultural ties.1 Welles’s inclusive, cosmopolitan persona and charismatic mastery of the mass media made him a likely Good Will Ambassador, even though he was only twenty-six years old at the time.

Welles’s interpretation of the mission of the Good Neighbor Policy was idealistic and radically progressive. He employed a staff of researchers to educate him in Latin American history and culture.2 His approach was to seek an unusual depth of cultural knowledge which he would then filter through his personal artistic sensibility. For the Rio Carnaval segment of It’s All True, he expanded his attention from street parades and elegant nightclubs to the city’s favelas – its hillside slums – in order to seriously explore the Afro-Brazilian roots of samba music. He quickly became an enthusiast. The surviving Technicolor footage of the 1942 Carnaval, both documentary and re-staged, suggests a celebratory vision of racially integrated urban life rarely, if ever, seen in Hollywood films of the era.3

Welles’s radically simpatico reading of the Good Neighbor Policy did not prove entirely palatable to all the participating authorities. Officials in the Brazilian government’s Departamento do Imprensa e Propaganda, who had originally proposed filming the Carnaval to attract tourists to Brazil, objected to aspects of Welles’s approach as it developed, as did commentators in the local press.4 Elements within RKO were completely at odds with Welles. Production Manager Lynn Shores’s reports to the home office damned Welles’s footage as “just carnival nigger singing and dancing”.5 On 11 April, Shores secretly informed the Brazilian Department of Propaganda that Welles had filmed in the city’s favelas, and a few days later complained to RKO, “[Welles] ordered day and night shots in some very dirty and disreputable nigger neighborhoods throughout the city.” The local press complained that Welles was filming “no good half-breeds … and the filthy huts of the favelas which infest the lovely edge of the Lake, where there is so much beauty and many marvelous angles for filming”.6 It is a sad fact that even during the brief window when US political pragmatism allowed Welles’s cosmopolitanism an official platform, a fifth column of racist provincialism helped crush the project.

Of course, there were many other reasons for the film’s incompletion, most to do with executive politics at RKO, of which Welles’s long version of The Magnificent Ambersons was another casualty.

Despite his occasional pastoral evocations – the Colorado frontier, sleigh rides outside Indianapolis, the fishing community in Fortaleza – Welles projected an essentially urban sensibility. He defined civilisation as ‘city culture’. Aside from the implicitly critical contrast between the racially segregated spaces of Rio de Janeiro, the surviving traces of the Carnaval film gesture towards a utopian vision of cosmopolitan city living: the population united by an inclusive Pan-American identity, its public spaces open to the people, and socially progressive urban planning.

The unusual challenges of filming It’s All True in Brazil also seem to have been pivotal for Welles’s development as an urban filmmaker. Barely two weeks after he’d finished filming The Magnificent Ambersons at RKO in Hollywood, he was in South America trying to film a wild, uncontrollable, and uncontainable real-life event: “shooting a storm”, he called it. The unorthodox process forced him to grapple with new challenges of representing a city on screen.

The trajectory of Welles’s Brazilian filmmaking in 1942, from Rio de Janeiro to Fortaleza, was a little like that of Welles’s film career in miniature: it began with a 27-person Hollywood crew and a plane’s worth of movie equipment, as well as anti-aircraft searchlights seconded from the Brazilian military;7 it ended with non-professional actors and a skeleton crew shooting with a single silent film camera.

* * *

It’s All True was intended to be a multi-part anthology of stories based on actual events. In its pre-Good Neighbor Policy phase, the focus was North America: stories about Canada, the United States, and Mexico. After Pearl Harbor it expanded to include South American narratives. But Welles never finalised a definitive structure, and at least seven segments were developed. Three were fully or partially shot but never edited: ‘My Friend Bonito’, ‘Carnaval’, and ‘Jangadeiros’.

During the early development of It’s All True, Welles assigned preliminary scripting duties to writers including John Fante, Norman Foster, and Elliot Paul. Welles’s own revisions would come at a later date, his method for radio dramas. But some of these scripts were never pursued further, and the extent of Welles’s involvement in their development is unclear. Some of the segments used urban settings, and there was a recurring interest in architects, but it can only be speculated how Welles might have pursued these aspects on film.8

‘The Story of Jazz’ was to have dramatised the life of Louis Armstrong, playing himself – “except in knee pants”, Welles noted.9 Duke Ellington was contracted to write the music and participate in the development of the story. An early treatment from July 1941, written by Elliot Paul, was titled ‘Jazz Sequence’. Welles appended a page of comments which clarified his conception of the segment as “a dramatised concert of hot jazz with narrative interludes by real people”.10 The treatment follows Armstrong’s career from New Orleans to Chicago to New York. It is remarkably observant of the growth of jazz within specific urban spaces. It uses a New Orleans railway track as a recurring motif; Louis, first as a five-year-old boy, collects “usable pieces of coal which have fallen from the train”.11 Louis meets his mentor King Oliver in a New Orleans funeral band. There are marching band battles, ‘cutting contests’, and legendary New Orleans locations such as Mahogany Hall and the Frenchman’s.

One passage in this early treatment, which surely shows the guidance of Welles, outlines another incarnation of his Heart of Darkness sound scheme: diegetic music to spatially orientate the viewer outside Mahogany Hall in Storyville. Paul’s treatment notes:

As we go from one fanlight to another we hear band music to match: that is to say, Oliver’s music fades out under somebody else’s; then somebody else’s is taken over by still somebody else’s. Sometimes the music is fast – sometimes slow – sometimes its just piano music. Always it representative New Orleans jazz.12

Later in Paul’s treatment there is crosscutting between two Chicago nightclubs: the banal performance of the white Original Dixieland Jazz Band – “with all the stunts and gags” – and the exciting black Armstrong and Oliver band.13 This kind of juxtaposition occurs in Welles’s later sketches for the Rio Carnaval material, an emphatic contrast between the black originators of authentically American music and the white musicians who create a commercially acceptable version for white listeners in segregated spaces.14

Further continuity draft screenplays were written by Paul in August and September 1941.15 Duke Ellington formally signed his contract with Mercury as composer in May 1942 while Welles was in Brazil, but the segment was never shot.16

Nevertheless, Welles’s concept had an afterlife. New Orleans (1947), a later RKO jazz film made entirely without Welles’s participation, seems to have evolved from Elliot Paul’s material (he was co-credited for ‘original story’). The film featured Louis Armstrong in a small role and its plot mirrored the “geographic trajectory” of ‘The Story of Jazz’. Following the film’s release, Welles’s associate producer Richard Wilson sought legal advice on its similarities with Welles’s project.17 Later, Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s CBS television special and album A Drum Is a Woman (1957) used a jungle-to-nightclub narrative to tell the history of jazz. At the time of the broadcast Ellington recalled Welles’s invitation to participate in It’s All True: “Then there never was a movie,” Ellington told Newsweek, “but I never forgot the theme.” One Ellington critic notes that A Drum Is a Woman “implicitly portrayed music as a historical and cultural link between African, African American, and Latin American peoples, and implicitly argued for a Pan-African unity”.18

Another untitled and uncredited script about jazz partially survives in typescript in Welles’s archives. It is undated but was probably written around 1945.19 This fictional story also follows the origins of the music from the jungles of Africa, across the Atlantic by slave ship, to New Orleans, and then to Chicago and New York. The story properly begins at the turn of the century and involves Kit, a white foundling in New Orleans, and Reggie, the son of her adoptive father’s black housekeeper. Despite the lack of a credit, there is enough Welles-style humour to suggest he had a strong role in its writing. A courtroom sequence, in which the grown-up Kit, a jazz pianist, defends jazz as an art form against the ‘Pure in Heart League’, has a humorous quality which anticipates the farcical courtroom in The Lady from Shanghai. One racist commentator, who believes jazz is “the ignorant clamor of savage black men”, is called as an “expert” witness for the prosecution. The “expert” works backwards through his professional experience – six years as a critic with the Evening Telegram, eight years with the New York Opera House, twelve with the Paris Symphony, fourteen with the Milan Opera Company, eighteen years with the Budapest choir, and so on. When he finishes, Kit’s attorney cross-examines the witness: “Just one question, Mr. Travers. For how many years now have you been dead?”20 It’s difficult not to imagine a flustered Erskine Sanford smashing down his gavel to silence the uproarious laughter of the court.

Even more so than ‘The Story of Jazz’, the script seems to gesture towards connecting the development of jazz to the development of cities; Kit’s father, Latimer, is a New Orleans architect conveniently involved in designing “cheap bungalows” and “modern housing”.21 But little evidence about this project survives in the Welles archive.

‘Love Story’ was to have focused on a romance between Italian immigrants in the United States. It was supposedly based on the parents of its writer, John Fante, author of the novel Ask the Dust (1939). In Fante’s ‘1st Draft Continuity’ script, finished in the summer of 1941, Rocco is a hod carrier who wants to be an architect, and pretends to have achieved material success to impress an Italian girl and her family. The setting is the San Francisco Bay Area in 1909. The script takes in the city’s cable cars, a vaudeville theatre, a skating rink, a beach, a ballroom, a ferry, and a suburb at the end of the street car line in Sausalito, a “block of scattered, cheap homes, treeless and lonely” where Rocco has a “box-like, two-story, weather beaten frame house”.22 The variety of historical urban settings suggests that the film could have become another part of Welles’s U.S.A. alongside Kane and Ambersons. Catherine Benamou, the dean of It’s All True research, notes that the world depicted in ‘Love Story’ is modernising, and its characters interact with a built cityscape and mixed population representative of these changes.23 But the settings show more promise than Fante’s weak melodramatic romance and its ethnic stereotypes. It does not seem that Welles revised Fante’s work.24

Beyond the San Francisco setting, there are other hints at what would later become The Lady from Shanghai. The early scenes move between a penny arcade, a scenic railway, a ‘Foolish House’, a midway, and a crystal maze inside an amusement park.25 The hall-of-mirrors concept would also feature in the unproduced Don’t Catch Me.26

Another part of It’s All True, ‘My Friend Bonito’, was based on a story by the filmmaker Robert Flaherty about the friendship between a Mexican boy and a bull raised to die in the corrida de toros. The bull would escape death after exhibiting exceptional bravery. Its screenplay was written by Fante and director Norman Foster, who began production in Mexico in September 1941. After he recalled Foster to Hollywood to direct Journey into Fear, Welles intended to himself film the missing scenes in Mexico on his way back from South America. This proved impossible after RKO’s cancellation of It’s All True.27 ‘Bonito’ was never finished, but some of the black-and-white negative survived and several minutes were presented in the posthumous documentary It’s All True: Based on a Film by Orson Welles (1993). In this assembly the boy and Bonito are seen playing together in material shot at the La Punta hacienda in Jalisco. There is another sequence showing the blessing of animals by a village priest. This part was shot at the Zacatepec ranch in Tlaxcala.28

* * *

They’re closing down Praça Onze

There will be no more samba schools

The tamborim cries, the shanty towns cry…

put away your instruments,

the samba schools won’t be parading today.

– ‘Adeus, Praça Onze’ by Herivelto Martins and Grande Otello29

Amid the maelstrom of his daily activities in Rio, Welles commissioned detailed research reports to help him understand Brazilian culture. The research helped him find a meaningful structure for the documentary film material he had shot during the four tumultuous days of Carnaval and guided the re-staging of the festivities. Welles’s assistant Richard Wilson said: “As we learned more down there, the structure of the Carnaval subject altered. As Orson filmed more, it altered. There were several structures conceived for this subject, and several structures for the whole film.”30

Many of these reports survive in the Mercury archives. Welles read about Brazil’s ‘macumba’ ceremonies (“a kind of fetish lethargy”), the history of the rubber business, “Primitive Inhabitants of Rio Grade do Sol”, the “History of Rio Grande do Norte and Legends, Customs and Traditions of the Northeast”, “The Origin of the Word Gaucho”, “Brazilian Independence and Jefferson”, and “Holy Week in Ouro Preto”. There is a long report on how Rio had developed from its beginnings to the imminent razing of the city’s Praça Onze (Square Eleven) to make way for Avenida Getúlio Vargas, “an 80 meter wide avenue constituting an important longitudinal axis of the city”. The “colossal” Avenida, already in progress, would require the destruction of entire blocks, four churches, and many other tall buildings.31

The city’s samba schools, which researcher Robert Meltzer reported had replaced the banned cordãos (local gangs), traditionally fought in Praça Onze.32

A research paper by future Brazilian director Alex Viany explains:

At first, Praça Onze was – as it was … with all new public places in Rio and other world capitals – almost a privilege of the rich or the whitemen. When the city grew and life in the center began to get more and more expensive, the negroes and the poor went to the suburbs and the hills. They get back to town in Carnaval. Praca Onze is like the African embassy in Rio during Carnaval … [its] feasts are like Harlem jam-and-swing sessions elevated to the highest degree. […] The white workers also go to Praça Onze during Carnaval. There, among their negro brothers they are happier and more free than in the middle-class Carnaval hangout, Avenida Rio Branco, or than in beautiful but snobbish Copacabana. Praca Onze can be taken as a democratic symbol, as a center of irradiation… there you’ll find the most genuine freedom in thinking and speaking. […]

The reaction of the negroes to the demolition of Praca Onze was one of resignation. They know that someday their hills shall be demolished too. But they also know that they must have better houses in better conditions by then. They believe in progress and want to cooperate. But they want to see progress working – not in promises. That’s why they are building an obelisk to President Getúlio Vargas near Praca Onze. They (the workers of Brazil) believe in his promise but want to see them working. The obelisk is something of a reminder.33

Viany adds that the obelisk was actually the initiative of government-controlled workers’ syndicates, not a spontaneous move by the workers themselves.

These commissioned papers, many by Brazilian scholars, indicate Welles’s serious intent to film more than a colourful background for a propagandistic travelogue. He would reimagine Rio de Janeiro on screen with a grounding in its history, culture, economy, flows of communication, racial politics, and power relations, all in aid of Pan-American unity against fascism.

* * *

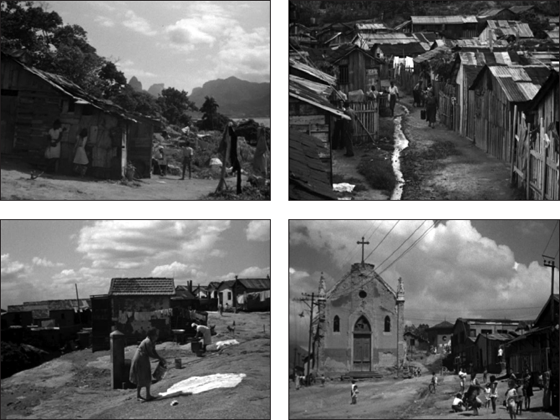

Through to the end of May, Welles and his crew filmed re-stagings of the festivities at Cinédia Studio, at the Teatro Municipal, and in the Quintino neighbourhood. He also entered the city’s favelas to film with both a handheld camera and his Technicolor crew.34 He later said the crew was attacked in one place by mysterious thugs who threw rocks and empty bottles.35

Welles had by now conceived an additional Brazilian segment for It’s All True, a re-enactment of the recent ocean journey of four peasant fisherman by jangada raft some 1,650 miles from Fortaleza on the north-eastern Brazilian coast to Rio de Janeiro to appeal to dictator Getúlio Vargas for basic social benefits.36 In March Welles temporarily left Rio to scout locations in Fortaleza. He intended to return in the winter to film the rituals of the fishing community and the commencement of the jangadeiros’ journey. But before that Welles brought the four original jangadeiros to Rio to film the conclusion, a re-staging of their arrival in the city – which, contrary to history, would now coincide with the Carnaval festivities. However, during preparations for filming on 19 May, the jangadeiro leader, Jacaré, drowned in an accident off the coast of Rio.

Shortly after Jacaré’s death, Welles wrote a long defensive memo to RKO.37 His filming methods had been reported with persistent negativity by RKO finks such as Lynn Shores, and he had been pressed to explain and justify his unorthodoxy to the brass back in Hollywood. The Magnificent Ambersons had already been removed from his editorial authority, and RKO had begun to reduce Welles’s financial and logistical resources for It’s All True. They refused to supply Technicolor stock for the upcoming jangadeiro segment in Fortaleza, which would now have to be shot in black and white at the cost of aesthetic continuity with the Carnaval material.38

Surviving frames from Welles’s Technicolor footage from the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, 1942 (Source: It’s All True: Based on a Film by Orson Welles, 1993)

In the memo Welles defined It’s All True as “neither a play, nor a novel in movie form” but instead a “magazine”, with the Carnaval sequence “a feature story” within that format. He added with enthusiasm that “the sheer immensity of Rio’s Carnival is hopelessly beyond the scope of any Hollywood spectacle”. There was only one possible approach considering the little preparation he’d been afforded:

We often had no choice but to set up our camera and grind away until we got something usable. We shot without a script. We were forced to… I as director, was always the one to be informed rather than the people working under me.

Welles wrote that he immediately recognised that Carnival was too complex to be comprehensively documented on the fly and that re-stagings were inevitable. What’s more, the cemented structure normally provided by a screenplay in advance of production had to be postponed until the film and sound recordings could be assembled and synchronised back in Hollywood; the crew were obliged to “take out all the paying dirt and ship it halfway around the world from the place where it was mined. We won’t get the gold until we get back to where operations are possible.”

Welles’s memo is a key provisional document about the ‘Carnaval’ segment while he was still working on it in Rio. It is his attempt to define the themes and structure of the work-in-progress under duress. Although Welles appended, at RKO’s request, a more traditional treatment – “a design for the main architectural lines of the Carnival film” – he did so under gentle protest. Both Kane and Ambersons had been meticulously scripted and planned shot by shot; it’s clear Welles was exhilarated to be improvising on location without a traditional script as he had done three and a half years earlier making the film segments of Too Much Johnson.

The memo emphatically makes the case for the exceptionalism and cultural importance of ‘Carnival’. With great clarity Welles argues that logistical challenges had made it necessary to invent a new process of filmmaking. He clearly thrived on the challenge, but felt it unfair to be criticised for circumstances outside his control.

It was understood by all concerned before I left that Carnaval would be shot on the cuff. […] The task of learning about Carnaval, and translating what we learned into film, has been very far from easy.

It was, after all, a semi-documentary. Welles claimed he and his collaborators had been “writing the Carnaval picture every night” in the form of extensive discussions with local experts. This was “the sort of daily work which has necessarily taken the place of actual writing”. As an example, Welles appends excerpts of “minutes of these meetings” that document a democratic, well-informed debate on incorporating a romantic choro song and the practicalities of how the choro scene should be filmed. Welles makes a bold pitch for these notes as “the nearest thing we have to a script”. By this method, the ‘script’ serves as a detailed record of the collaborative creative process rather than a meticulous pre-plan to be executed with a minimum of needless expense. It leaves open wide space for improvisation during both the filming and post-production.

In the future Welles would write screenplays that met strict industry standards only when he was working within an institutional context or when he was attempting to independently raise finances. Discussing his bullfighting project The Sacred Beasts in 1966, he said he planned to discard the many scripts he had written and shoot without one.39 Writing was a crucial part of Welles’s creative process – the mountains of messy drafts in the archives prove that – but as he said in 1964, “I prepare a film but I have no intention of making this film. The preparation serves to liberate me.”40

Nevertheless, also appended to the memo is that ‘Treatment for the Film Itself’ demanded by RKO. It is possibly Welles’s earliest surviving attempt to lay out a formal plan for the Carnaval footage he was still shooting. He intends to use as the structuring conceit samba, which, in the words of Catherine Benamou, will provide “the lens through which to gauge the effects of modernization on human relations and social identity” in Rio de Janeiro.41 Welles writes:

Samba comes from the hills that rise above Rio, from the people who live in those hills – but there are those authorities who maintain that Samba is principally a product of Rio’s Tin Pan Alley. The best opinion and, most importantly, dramatic interest, sustain the hill theory… The point needs to be proved and illustrated…42

This ‘hill theory’ had not been unanimously supported by Welles’s ‘brain trust’ of experts. Local researcher Rui Costa reported:

To say that the samba was born in the hills is as much a matter of opinion as to say that Venus was born in the waves of the sea… the truth is that all elements of the city, from all the sections, cooperate to produce the samba.

Costa notes the one-time usefulness of the favelas as a rehearsal space because it had been easier there to evade the police, who tried to prohibit late-night noise. However, the composers deserted the favelas following the invention of radio and recording studios down in the city. He describes the subsequent state of the favelas’ samba schools as “mediocre affairs, without any of the choral discipline of the old times”. Costa concludes:

At any rate, perhaps it’s just as well to allow the people and the literal-minded to keep the sweet conviction that the samba was born in the hills. It’s a sweet and poetic tale which after all doesn’t harm the real trend of things…43

The American Robert Meltzer’s long and entertaining memo to Welles on the musical genealogy of samba lamented the lack of existing written studies, which meant that the music’s origins were still mythical and debated. He sought advice in Rio from such experts as composer Heitor Villa-Lobos and encountered conflicting opinions. Meltzer settled for the imprecise conclusion that

it’s neither the Colonist of the North nor the composer of Rio, neither the barefoot bacteria from the hills nor the Fireman’s Band, neither the European and American influence nor the troubadours, neither the denizens of Villa Isabel nor the sons of the slaves – none of these can claim responsibility for Samba’s birth and appearance. All of them together, each in its own way, had a great deal to do with that appearance, too, a very great deal. […]

It takes all sorts of things to make a world, but it seems to take even more to make a Samba.44

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Welles went for the sweet and poetic ‘hill theory’ as the structural device of this version of ‘Carnaval’. This served to highlight the central contribution of Afro-Brazilians to Rio de Janeiro’s culture and to recognise the city’s peripheral, impoverished underclass. It also provided the opportunity to canvas the city’s many diverse spaces.

Welles mentions Rio’s “kinship” with New Orleans and how “between American Jazz and American Samba there is much in common” (one of several instances where Welles’s Good Neighborliness extends to calling the entire hemisphere ‘America’ in the South American fashion). Meltzer, himself a jazz pianist, had come to the conclusion that samba is quite different from jazz because it privileges composition over performance.

But no matter. Welles lays out his plan:

Here we are, up in the hills. Here is the jungle, trying to push its way back down into the city; and below us, profuse and glittering, is the city itself, the bays and the beaches, the skyscrapers – beyond, the breathtaking monuments of other hills. We’re up the Favellas [sic] now, rude dwellings (now being replaced by the Government of Brazil with better homes for the people). Here, in a special place of its own, distinguished by its special structure, its flowers, its curtains, its large fenced-in yard, is a typical School of the Samba.45

Welles introduces the Afro-Brazilian composer, musician, and dancer Grand Otello as a central figure. In the weeks before Carnaval, Otello introduces a new samba to the musicians at a samba school. The film will cut to the same song being recorded in one of the city’s radio stations by a sophisticated female singer. Now “the city has taken up the new Samba”.

Welles introduces the percussion instruments of samba, as well as other props of Carnaval: “perfume-throwers … masks, serpentina, confetti, noise-makers”. He then cuts to four representative and “widely contrasting locations”46 of the bailes or dance venues: the Teatro Municipal, the Independencia, the Teatro da Republica, and the Rio Tennis Club. Each represents a different class of carioca and each is alive with festivities and music (‘marchas’ rather than ‘sambas’). A woman in the Tennis Club sings a romantic choro during an interlude before the festivities resume.

The people come down from the hills early, dressed up in the costumes they’ve been preparing for weeks: clowns, Hawaiians, Cossacks, Bahianas, tramps, animals, Indians, monsters – everything and anything. Down they come from the hills, down the paths and rough roads to the paved streets and the little plazas in the suburbs […] The crowds jamming the city’s outskirts choke the narrow streets and the wide streets: a rising river of humanity that moves together in the channels defined by the shops and houses. There is nothing placid about this movement. It is all whirlpools and eddies. And always there are the rhythms of Carnaval’s music, the gay noise of thousands of voices singing without inhibition in the open air.47

The revellers appropriate the city’s public transport in their movement towards the city centre. An open street car is so overcrowded it becomes

a great clinging globule of humanity with a trolley sitting on top. By this and by other means, the people move and gather in the center of Rio. The tens have become hundreds, the hundreds thousands, and the thousands a million. Their voices combined in song now produce a mighty roar that sifts into the farthest alley and rises up to the top of the tallest skyscraper.48

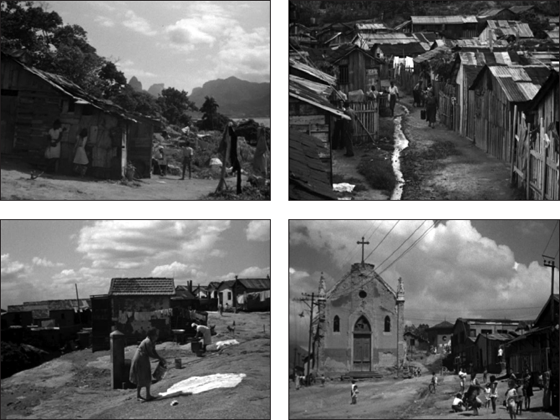

Surviving frames from Welles’s Technicolor footage of the Carnaval of Rio de Janeiro, February 1942 (Source: It’s All True: Based on a Film by Orson Welles, 1993)

* * *

Next, Welles includes a fictional scene, playing himself as a newcomer to Rio:

A roof garden on top of a skyscraper in the middle of the city. All around are more skyscrapers, some finished, some in work. Beyond are Rio’s sumptuously beautiful hills. From the street there rises the huge roar of Carnaval, throbbing like a powerhouse. Close to us people are singing the samba ‘Farewell, Praça Onze’. This is distinct from the multiplicity of other sounds, other rhythms – increasingly so during the following scene.

An architect’s stand on trestles displays a plaster model of part of the city. Standing beside this is a young lady whom we will call Donna Maria. She looks efficient and attractive. There is no mistaking her officialdom or her sex appeal.

Welles and Donna Maria discuss the samba song and the important public square whose imminent disappearance it laments. Welles remarks that “now it has to go to make room for a big new street”.

DONNA MARIA

The people love it very much – so they made up this song about it to bid it goodbye. Senhor Orson, you’ve never been to Rio before, so you can’t know how our city’s been changing. Over there we used to have a mountain. A little while ago we moved it away. Now the city is several degrees cooler and the traffic problem is simplified.

WELLES

I think Rio can spare a few mountains and still be the loveliest city in America.

DONNA MARIA

We thought so, too. Now here’s a model of our new Avenue – Avenida Getulio Vargas.

INSERT – MODEL OF AVENIDA GETULIO VARGAS

WELLES

Right there (my hand points) – Isn’t that where Praça Onze is now? (back to scene)

DONNA MARIA

It won’t be by the time this picture’s shown onscreen. The city’s going to be tremendously improved, but, of course, lots of people will still have saudades for Praça Onze.

WELLES

Saudades – Ladies and gentleman, I’m no interpreter, but I now offer you a Portugese expression the English language ought to adopt because we haven’t got its equivalent – saudades.

DISSOLVE during the next few words to title:

SAUDADES

Over this I continue.

It means heartache – something like that – Sentimental memory, lonesomeness – a longing remembrance of something past, or of someone gone away…

Welles believes ‘Farewell, Praça Onze’ will become a standard like ‘Basin Street Blues’ or ‘Swanee River’.

WELLES

No, Donna Maria, I don’t think you Cariocas are going to forget Praça Onze – that song won’t let you. Next year, of course, there’ll be a new samba about the new street, and I’m all for that – for new sambas and new streets. (to camera) You know, Rio’s one of the only beautiful old towns where new things are even more beautiful than the old ones. Of course, it’s just as hard here as it is anywhere else to say goodbye to the past – but you can always keep your mind off the past if you’re busy enough with the future, and Rio’s plenty busy. Right, Donna Maria? You’ve got even more plans here than you’ve got memories – more hopes than regrets, more dreams than saudades.

DONNA MARIA

The hills up there, for instance, where the poor people live, where the Schools of Samba come from – you were up there photographing one of them, Senhor Orson – do you know we’ve got new housing projects for all those places – model homes? They’re going up right now.

WELLES

That’s fine.

DONNA MARIA

Just wait and see…

The ‘Praça Onze’ tune sounds louder, more insistently. She smiles, acknowledging its effect.

DONNA MARIA (Cont’d)

Of course, we can’t deny we’re sentimental.49

Welles’s dialogue with this fictional Brazilian official is characteristic of his interpretation of his mission on behalf of the Good Neighbor Policy. It would have been another exercise in charismatic but calculated diplomacy. Rather than attack the cynicism of the Vargas regime in what was surely an authoritarian usurpation of public space, Welles calls the dictatorship’s bluff, accepts its urban development plans at face value, and pushes the most utopian and progressive reading of those plans. The destruction of the culturally important square is permissible because it is linked, Welles indicates, to socially progressive aspects of the city’s modernisation, including the housing projects that will replace the slums of the favelas. It would have been a passive-aggressive attempt on Welles’s part to publicly defy the Brazilian dictatorship not to come up with the goods – in other words, the internal radicalisation of a policy by excessive endorsement. As pitched, Welles’s ‘Carnaval’ segment would have served like that ambiguous workers’ obelisk to President Vargas near Praça Onze – both a commissioned tribute and a reminder.

In this interpretation ‘Farewell, Praça Onze’ is not exactly a protest song against authoritarian control of the spaces of the city. Instead, the song gives popular expression to a very Wellesian sense of loss. Welles’s discovery of the Portuguese word saudade couldn’t have been more timely. His work in film to date is seeped in it.

Carnival had been increasingly institutionalised under Vargas; the samba schools had been forced to register with the authorities.50 Simon Callow is right to describe Welles’s endorsement of the Vargas regime as an “extraordinary piece of ideological flexibility”.51 At the same time Welles does not compromise on his radical commitment to celebrate the city’s marginalised black and indigenous people. And to be fair, this scene was sketched in a memorandum directed to RKO in the midst of trouble, as he was losing control of Ambersons.52 Welles had been forced to justify the It’s All True project and his methods, defend himself against damaging accusations, and present the segment as both commercially viable and in line with the OCIAA propaganda mission. But Welles was in risky territory. Welles had alienated officials in the Vargas regime by focusing on Afro-Brazilian and caboclo culture in both his documentary footage and his recreations.53

* * *

The treatment continues. Welles plans a “montage concert” of what he calls the ‘Praça Onze Suite’ which will show varied arrangements of the song as it is played in many venues of the city, beginning in Praça Onze itself. A similar montage occurs for the other samba hit of the year, ‘Amelia’, and introduces the character of a lost young boy named Pery who seeks his mother in the crowd. The two songs merge in the square and the competing singers busy themselves with a capoeira, the Brazilian fight dance.54

Welles intends to show the singer Linda Baptista performing in the racially segregated Casino de Urca, where Carmen Miranda was discovered;55 this is to be intercut with the same samba, ‘Batuque no Morro’, as sung in the streets in a parody of Carmen Miranda by Grand Otello, who has appropriated various pieces of women’s clothing. Welles explains:

The contrast is not only of voices, but of directions: the Carnaval of tradition is a celebration of the streets alone. But recent years have send a trend indoors to the Baile and the Casino. The contrast, as it’s illustrated by this song, isn’t extreme – but the raucous raggle-taggle jamboree of the streets and the more professional, if equally enthusiastic atmosphere of the nightclub, is interesting in juxtaposition…

We’ve seen people inside the clubs and dance halls at night; we’ve seen them outside during the day. Now we see them outside at night. We see them from the level of the streets themselves, and from the roofs of buildings. The total effect is breathtaking.

Welles also dubiously lauds the “unpoliced good behavior of Carnaval’s mob. Drunkenness has no part of the world’s biggest good time, since only champagne and beer are obtainable on Carnaval days, and besides, Brazilian good humour is so unaggressive that brawls are hard to find.”

The segment continues with footage of the parade down the city’s main avenue. There is an orgy of Pan-American propaganda. One float depicts five tall columns, the fifth symbolically toppled – “as the people believe it should be”. Then there are several spectacular musical numbers played by the Ray Ventura Orchestra in the Urca Casino, which ends as

Rio’s Carnaval becomes Pan-America’s Carnaval. Here, you realize, is one way of saying something that all of us in the Western Hemisphere are coming to recognise. The Americas, all the Americas together, are joined in fact as well as in idea, today rather than in the future.56

There is a brief return to the nearly deserted Praça Onze. ‘Farewell, Praça Onze’ plays in a minor key. A policeman carries the boy Pery home. Grand Otello wakes up and discards his broken tamborim.

A short coda shows the jangadeiros returning by plane to Fortaleza after their heroic quest. Welles as narrator dedicates the picture to the late Jacaré and “to his dream of the future!”57

* * *

Benamou considers Welles’s ‘Carnaval’ treatment in the tradition of the international cycle of city symphonies, and singles out comparison with Man with a Movie Camera, which goes beyond presenting mere social contrasts to show the city as “a collective consciousness” in flux.58

Welles’s treatment aims for an expansive reimagining of the city on screen. He approaches the challenge by proposing several innovative techniques. By mapping the passage of the music-making Carnaval revellers from the favelas – “this huge conservatory of the samba”59 – to Praça Onze, Welles illustrates the centripetal flow of Rio’s geographically marginal dwellers through the built passages of the city. This also radically asserts the cultural centrality of impoverished non-whites. Surviving Technicolor footage of the massed crowds moving through the streets, some shown at the conclusion of the 1993 documentary, depicts the happy and uninhibited mingling of races.60

Then there are the stark, ideologically loaded juxtapositions between different spatial and social zones of the city: Grand Otello’s authentic creation of a song in the favela samba school matched with a tamer performance of the same song in a radio studio; and the four venues for bailes with clear distinctions of race and class.

The dialogue with Donna Maria provides the film with a synoptic overview of the city as well as an ideological guide to interpreting that vision. The expansive point of view of the camera from the skyscraper roof in the centre of the city shows the Carnaval procession in its totality. The plaster model of the new Rio, including Avenida Getúlio Vargas, allows for an immediate visual comparison between the city of the present and the city of the future. The genial dialogue between Welles-the-outsider and Donna Maria as government official determines authoritatively the progressive significance of the urban changes.

The memo is a typically persuasive sketch by a cinematic visionary, but Welles was overly optimistic to believe he could get away with it. RKO continued to withdraw financial and logistical support for It’s All True. Undoubtedly moved to pay tribute to the drowned Jacaré, Welles prefaced his memo on ‘Carnaval’ with the assertion that he was now by necessity at work writing a “wholly new attack on the Jangadeiro story… No effort will be spared to hasten its completion.”61 And although RKO stopped further shooting of the Carnaval segment in Rio, they allowed Welles to continue making the jangadeiros story in Fortaleza on a paltry budget of $10,000 with a tiny crew rather than risk bad press after the death of Jacaré.62

* * *

Years later Welles would recall the new regime at RKO blaming him for having tried to make a film in South America without a script. He said, “I entirely sympathized with them, but it wasn’t my idea or project.”63

Even after It’s All True’s cancelation, Welles tried to persuade RKO to allow him to finish the film. He did some editing of the Carnaval and Rio-based jangadeiro material in Hollywood in September 1942,64 but plans for Twentieth Century Fox and Warner Bros. to take over the release of the film fell through. In another treatment pitched to RKO in September 1943, Welles persisted in including images from the favelas, “the real jungle, which still makes long hopeless war on the capital of Brazil”.65 This pitch was not accepted by RKO’s executives.

Welles kept trying. He bought the rights to the footage from RKO for $200,000 in 1944, and attempted to devise new fictional films that would draw upon the extant material.

One thriller script, also titled Carnaval, involved an American fighter pilot with amnesia named Michael Gard who slowly pieces together his memories of the 1942 Carnaval. It turns out his Czechoslovakian lover had almost been killed by Nazi soldiers, and her survival and escape to Mexico had inspired him to sign up to fight in the war. Grand Otello appears as himself.66

A treatment and production outline also survive for a mooted romance to be called Samba that was planned around 1945.67 Samba uses a framing narrative similar to that Welles planned for a contemporaneous film of Oscar Wilde’s Salome: a story told at a café table. The setting is a Copacabana all-night restaurant called the Samba School, which may have been inspired by the Café Nice on the Avenida Rio Branco, where, as Robert Meltzer had reported to Welles, many sambas were composed.68 By now, from afar, Welles perceived Rio as a romantic locale of foreign exiles, artists, and bohemians: “As we’ll learn, Rio de Janeiro is to the American hemisphere what Budapest is to Europe. This should partly help to explain ‘The Samba School’ and it’s customers.”69

He makes the case that he will be able to create a believable cinematic version of Rio by integrating the location-based Carnaval footage with new Hollywood material shot on cheap sets:

The street fronts the beach. Enough stage space should be allowed for cutoffs of buildings (in forced perspective) and a feeling of real distance for the mountains painted on the sky backing. The cafe is never seen except by night and early sunrise, so there is no need for this to look at all phoney.70

Welles notes what of the existing footage can be used for “processes and plates”71 (he also asserts his viability as a romantic lead: “If you don’t think I can play it, wait till I take off another 40 pounds!”72). In this treatment Welles revived key aspects of his earlier sketches. The ‘hill theory’ on the origins of samba is now voiced by that “dark cupid”, Grand Otello, who shines shoes at the café.73 ‘Ave Maria’ is sung as a samba, as it had been in the May 1942 treatment, and there is the juxtaposition of a new favela samba with its “slick and polite”74 interpretation on commercial radio. While the melodramatic love story is not particularly interesting, the treatment does provide insight into Welles’s practicality when working with very limited resources.

Welles would never be able to finish any incarnation of the Carnaval material. The rights reverted to RKO in 1946 when Welles was in financial difficulties.75

* * *

First the city, then a contrasting pastoral. Welles spent weeks from mid-June 1942 in Fortaleza and other cities on the Brazilian coast filming a re-creation of the preparations and voyage of the four jangadeiros.76 In Fortaleza’s traditional fishing community, Welles found another pre-modern paradise to celebrate and romanticise, this time in the context of a dignified political struggle for basic social benefits. The footage of the fishing community scrupulously avoids depicting any aspect of Fortaleza’s urban modernity.77 The exclusive emphasis is on the jangadeiro rituals of the sea and the coast. The wild human processions from favela to city centre in ‘Carnaval’ would have been counterpointed by an austere jangadeiro funeral procession across the coastal landscape of north-eastern Brazil.

Although Welles was never able to edit the jangadeiro footage, and never apparently even viewed the rushes, much of the original negative was rediscovered in 1981.78 Richard Wilson was behind the effort to edit the segment after Welles’s death, although he did not live to see it. An essentially complete silent film of almost fifty minutes named ‘Four Men on a Raft’, with sound effects and a score by Jorge Arriagada, provided the conclusion to the 1993 documentary. Despite somewhat lethargic pacing, this posthumous film is one of the most impressively realised items to emerge from the shadows of Welles’s oeuvre. It’s also a reminder that the canon of commercially released films does not give a full account of Welles’s artistic development. The segment was an adventure in the extremely low-budget, under-resourced, and improvisatory filmmaking Welles would not resume until he made Othello in Europe at the end of the decade.

NOTES