Back in the United States, Welles resumed a typically heavy schedule but was temporarily estranged from directing films. Aside from his ongoing work in radio drama, his performance as Rochester in Robert Stevenson’s Jane Eyre (1943), and magic performances for the military in the Mercury Wonder Show, his activities were political. He gave anti-fascist lectures, campaigned for President Roosevelt’s 1944 re-election, broadcast political commentaries, and wrote a daily column for the New York Post that was syndicated across the country through much of 1945.

He continued to support the Good Neighbor Policy. In March 1944 he wrote:

[I]n spite of all the dictators supporting it, in spite of its stumbling caution, its blind snobbishness, in spite of itself, the Good Neighbor Policy is an anti-fascist alliance, a community of nations bound together in the name of democracy. As such it is a preliminary sketch for world organisation.1

Later that year, Welles defined fascism as “always … some form of nationalism gone crazy”.2 Welles’s post-national vision of world government after World War II in some ways overlapped with Soviet-style internationalism, although he pushed a progressive rather than revolutionary agenda.3 At a 1943 convention sponsored by the United Nations Committee to Win the Peace, Welles had said:

The scaly dinosaurs of reaction (if indeed they notice what I’m writing here) will say in their newspapers that I am a Communist. Communists know otherwise. I’m an overpaid movie producer with pleasant reasons to rejoice – and I do – in the wholesome practicability of the profit system. I’m all for making money if it means earning it. Lest you should imagine that I’m being publicly modest, I’ll only admit that everybody deserves at least as many good things as my money buys for me. Surely my right to having more than enough is canceled if I don’t use that more to help those who have less. This sense of humanity’s interdependence antedates Karl Marx.4

After the war, Welles aggressively denied he had ever been a communist and sued the vice president of the American Federation of Labor for claiming he had communist tendencies. When grilled by gossip columnist Hedda Hopper in July 1947, he insisted he was “opposed to political dictatorship” and that “organized ignorance I dislike more than anything in the world”.5 By now everybody should have realised that Orson Welles wasn’t to be easily tamed by any organisation. However, throughout the 1930s and 1940s Welles had many Communist Party associates and participated in the campaigns of various front organisations.

In fact, Welles’s key political mentor, close friend, and future producer of his ill-fated Mr. Arkadin was Louis Dolivet, a secret Soviet agent. Born Ludovicu Brecher in Polish Galicia, Dolivet spent his childhood in Romania.6 He was in the service of the French Comintern from 19297 and was also an operative of the KGB. For a time in the 1930s and 1940s Dolivet was married to the sister of Michael Straight, an aristocratic communist spy within the US State Department who was also connected to the Soviet spy cell at Cambridge University.8 Dolivet seems to have first encountered Welles in Hollywood around 1942.9 He invited the young director to join his International Free World Association. Welles became an editor and penned articles for the association’s journal. It is not certain whether Welles knew about Dolivet’s covert Soviet activities, or that the International Free World Association was a Comintern front. Nevertheless, whatever its hidden objectives, the public message to which Welles lent support was progressive anti-fascism with the aim of international political cooperation.10

For a time Welles was mooted as a statesman and politician. Surviving letters between Dolivet and Welles testify to the mentor’s enduring belief in the young man’s extraordinary potential to be a key figure of the age.11 Dolivet supposedly believed that Welles would make an ideal Secretary-General of the nascent United Nations; Welles later claimed he’d been unenthusiastic about the idea.12 Welles later recalled, “Oh, he had great plans! He was going to organise it so that in fifteen years I was going to get the Nobel Prize.”13 Dolivet wasn’t alone in his optimism. If Welles is to be believed, President Roosevelt personally encouraged him to run for political office. Welles also considered running for the senate in his home state of Wisconsin in 1946 against newcomer Joseph McCarthy, the eventually disgraced politician who would come to define the reactionary mood of the coming years.14

In 1945 Welles edited a daily newspaper and made broadcasts from the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco. Around this time his utopian hopes for postwar world government dimmed. Welles later reflected to his former school master Roger Hill:

I remember driving to the airport after witnessing and reporting on the founding charter of the United Nations that established “equal rights for large and small nations,” thinking that the starry-eyed days were over. Even then you could see that the lines were drawn between the east and west. You could see from the Russians that there was no hope of a dialogue. I went to San Francisco starry-eyed as you say, but I left pretty much the realist I’ve remained ever since.15

Welles’s postwar anti-fascism increasingly focused on race issues. Unlike many of his peers, Welles directly equated racism with fascism, and was more fearlessly outspoken on civil rights than probably any other white American of his celebrity. His campaign for justice over the blinding of black veteran Isaac Woodard, Jr, by the Georgia policeman Linwood Shull was a particular passion in mid-1946.

In the midst of this consuming political life, Welles produced an ambitious stage adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, with original songs by Cole Porter. He also continued to try to make films. He had fruitlessly pursued new dramatic ideas to make use of the Rio Carnaval footage and worked on editing ‘My Friend Bonito’ with Jose Noriega. He bought the rights to Don’t Catch Me and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince and developed their screenplay adaptations. He developed projects for independent producer Alexander Korda, including War and Peace, Cyrano de Bergerac, and Oscar Wilde’s Salome.16 None of these films were made, but Welles was able to return to cinema with two thrillers that responded to the postwar political order.

Leftist filmmakers such as Edward Dmytryk, Abraham Polonsky, Jules Dassin, and Robert Rossen enjoyed a short-lived prominence in Hollywood after the war. These particular directors were active in the production of those crime melodramas retrospectively categorised as film noir. Noir came to be defined by mythical character types, dark and fatalistic narratives, and bleak urban settings, and drew on a visual language indebted to German Expressionism but which could nevertheless extend to semi-documentary realism. The cinematography of Citizen Kane (and its complicated flashback structure) had also been a seminal influence. Noir proved to be a language to express the moral and political darkness beneath the supposed tranquillity of the postwar years, and was briefly a venue for a politically radical perspective on big business, political corruption, and crime.17

This brief opportunity for left-wing filmmakers coincided with labour unrest and mass strikes across the nation – and also at Hollywood’s film studios. American workers had long postponed demands for improved working conditions and pay during the war (Welles began directing his independently produced noir The Stranger at the Universal Studios lot in October 1945, just after the national strikes began). But the reactionary backlash was swift. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 effectively outlawed strikes and the House Un-American Activities Committee began to purge leftists and labour organisers from various industries under the banner of anti-communism.18 In the film business, left-wing filmmakers were intimidated into allegory or silence. Some were imprisoned, others blacklisted, exiled, or pushed into betraying others. Welles all but vanished into a long European exile.

Dennis Broe’s political historiography of film noir traces a consequent shift away from the immediate postwar period’s “outside-the-law fugitive protagonist” – the sympathetic working-class character, often a war veteran, forced into crime, usually by someone in a dominant class position. Key examples include the protagonists of The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Lewis Milestone, 1946) and Raw Deal (Anthony Mann, 1948). By contrast, the heroes of noirs from 1950 to 1955 tended to be authoritative law enforcement protagonists.19

Welles more or less fits into this political historiography of noir. The trajectory of his Pan-American thrillers from the late 1930s to the late 1950s reflects his growing sophistication as a political thinker alongside his expanding cinematic virtuosity. During the Roosevelt era Welles scripted variations on the fascist infiltration plot, presenting fascism as an alien ideology that would be crushed by strong democratic institutions and international support for the war effort. Welles’s role as an ambassador for the Good Neighbor Policy and a campaigner for Roosevelt was compatible with this view. In his wartime screenplays and in his activism he endorsed the progressive anti-fascism of official intentions from a position within the political establishment, even if this demanded some overly generous – or even disingenuous – interpretations of Allied policy.

But The Stranger and The Lady from Shanghai, his back-to-back postwar noirs, straddle a pivotal shift in Welles’s political identification from the centre of power to the periphery after the death of Roosevelt. The Stranger revives the infiltration plot and presents an American Nazi-hunter protagonist as the heroic embodiment of postwar internationalist justice.20 But soon after making that film Welles abruptly abandoned his optimistic depiction of American officialdom. Moreover, fascism ceased to be an alien force infiltrating democratic society; it was now a danger arising from within the institutions of power.

Perhaps inevitably, the heroic anti-fascist crusader was pushed into the margins. Welles described Michael ‘Black Irish’ O’Hara, the near-penniless drifter hero of The Lady from Shanghai, as “a poet and a victim” who “represents an aristocratic point of view” as had Jedediah Leland in Kane. In Welles’s terms, ‘aristocratic’ was a superior moral quality rather than a class position, “something connected to the old ideas of chivalry, with very ancient European roots”. The aristocratic figure lives outside “sentimental bourgeois morality”.21 Mike’s naive medieval chivalry leads him to be compared to Don Quixote, but he is the only character with a shred of real conscience in the cynical world of the rich. He is unimpressed by their wealth and believes it “very sanitary to be broke”. He has impeccable anti-fascist credentials as a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. A legendary rabble-rouser to his fellow sailors, the radio labels him a “notorious waterfront agitator”. He is an anti-authoritarian with good reason to distrust the police. The wealthy frame him in a labyrinthine plot and use the institutions of American law to railroad him to the gas chamber. The studio’s heavy post-production control of Shanghai only somewhat dulled the film’s anti-authoritarianism.

Why this sudden change in political identification? Welles wrote the Lady from Shanghai script through the summer and early autumn of 1946, exactly the time he was engaged in a public crusade against racist police brutality in the Isaac Woodard case. The following year he left the United States as reactionary forces abused the power of American political institutions to crush left-wing activism in the name of anti-communism. Welles’s subsequent antifascist projects abandoned the infiltration plot in favour of vastly more nuanced illustrations of institutionalised corruption. In fact, his politics became more deeply radical.

* * *

Film noir is overwhelmingly an urban mode of cinema, situating its melodrama in the alienation, violence, sex, and corruption of the mid-century city. Noir’s cinematic cities draw on many sources, including the traditions of hardboiled crime fiction, German Expressionism and the related Kammerspiel and street film of the 1920s, Hollywood gangster films, documentary street photography, and existentialism.22 Within the cycle are cinematic reimaginings of actual cities, most commonly the distinct locales of New York and Los Angeles. There are also fictional cities that exist more in the realm of myth, such as the comprehensively corrupt and isolated small industrial city, an archetype descended from Dashiell Hammett’s Poisonville in his novel Red Harvest (1928).

The noir worldview – bleak, violent, fatalistic – bridges these diverse urban settings and stylistic modes. What Richard Slotkin writes about the imaginary landscape of the western is equally applicable to the cities of noir:

The history of a movie genre is the story of the conception, elaboration, and acceptance of a special kind of space: an imaged [sic] landscape which evokes authentic places and times, but which becomes, in the end, completely identified with the fictions created about it. […] The genre setting contains not only a set of objects signifying a certain time, place, and milieu; it invokes a set of fundamental assumptions and expectations about the kinds of events that can occur in the setting, the kinds of motive that will operate, the sort of outcome one can predict.23

The settings of The Stranger and The Lady from Shanghai are in fact rather atypical for the noir cycle, but they served Welles’s themes in a rapidly disintegrating political climate. After an early sequence in a dangerous South American port city, The Stranger is set in a mythical American small town with pastoral fringes. Port cities – New York, Acapulco, San Francisco – dominate the settings of The Lady from Shanghai. The port city, already a key setting in the Heart of Darkness screenplay and in Journey into Fear, provided an aptly cosmopolitan milieu for Welles’s political melodrama as anti-fascism was squeezed from its place in the wartime political establishment out to the periphery and soon into exile. These are crossroad cities whose spaces occasion the meeting of characters of different nationalities and classes in the postwar upheaval. In these cities everybody is under surveillance, but Ambleresque anxiety over identity documents is offset by the prospect of wiping clean the slate of identity and thereby dodging responsibility for the horrors of history.

* * *

The Stranger is probably Welles’s least admired film. Independently produced by Sam Spiegel and International Pictures, The Stranger evolved from a story treatment called ‘Date with Destiny’ by Victor Travis and Decla Dunning (an earlier version of the story by Travis dated back more than ten years).24 John Huston and Anthony Veiller, who had recently worked on the adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s story ‘The Killers’ for the eponymous 1946 film directed by Robert Siodmak – a noir masterpiece indebted to Citizen Kane – developed the adaptation of The Stranger before Welles was invited to star and direct. The story concerns the exposure of a German Nazi posing as a respectable American citizen in a small town shortly after the end of World War II. Welles’s performance as the Nazi is relatively weak.

Welles worked on a ‘Temporary Draft’ of the script dated 9 August 1945, co-credited with Huston; it reflects Welles’s provisional ideas for the film before officially signing his contract. But that temporary script was subject to pre-production cuts on the order of editor Edward Nims, who favoured retaining only what he deemed to be essential to the plot. A particular casualty was the long sequence in South America. About twenty-five pages of material from the ‘Temporary Draft’ was lost.25

Welles’s working copy of his subsequent 24 September shooting script, as it survives in the Mercury files, was embellished with coloured replacement pages until after the start of shooting on 1 October. This copy also contains Welles’s pencilled rewrites and crossed-out sequences. Researchers have had trouble establishing exactly what was dropped from the shooting schedule and never filmed, and what was filmed but eliminated in the editing room by Nims without Welles’s participation.26 Some of the pencilled-out sequences in the shooting script actually survive in the final cut of the film, which suggests Welles may have been using his script to prepare an edit he was never able to realise himself. In any case, the shooting script sketches a more psychologically complex and visually interesting version of what ultimately made the producer’s final cut.

It begins one night in the fictional town of Harper, Connecticut. Mary Longstreet is drawn from her bed in a dreamlike state to cross town to the church clock tower. The church is soon surrounded by a mob of armed townsfolk; a scream announces a fight at the top of the tower, and two unidentifiable figures fall. Then we flashback to Wilson, a pipe-smoking American with the Allied War Crimes Commission, who decides that war criminal Conrad Meinike should be allowed to escape from prison in a risky gambit to lay a trail to a Nazi mastermind.27 Wilson tracks Meinike by ship to a South American city, where Meinike reconnects with the Nazi underground, is provided with a new identity and passport, and learns the present whereabouts of Franz Kindler. One of Wilson’s South American agents, Señora Marvales, is murdered by dogs during the surveillance of Meinike.

The story shifts to Harper, where Kindler is posing as a history teacher with a passion for antique clocks named Charles Rankin. Rankin meets and romances Mary, the naive daughter of a Supreme Court judge.

Meinike arrives in Harper by bus and lures Wilson, who has followed him without much discretion, to a brutal ambush in the local high school gymnasium. Meinike tracks down Kindler-Rankin and preaches spiritual redemption. Rankin leads him into the woods and strangles him. He then proceeds to church to marry Mary as scheduled.

Meanwhile, Wilson has recovered from the attack and remains in town under cover as an antiques dealer. On that pretence he meets the Longstreets and, soon after, Rankin himself. Wilson comes to believe that Rankin is really Kindler after he expresses the bizarre opinion that Karl Marx was not German because he was Jewish. Wilson confronts Mary’s brother and father with the truth and begins to close in on Rankin. After Meinike’s body is found, Wilson shows Mary footage of the liberation of a Nazi death camp. Meinike is shown in the film under arrest. Mary, however, continues to believe her husband’s explanation that Meinike was merely a blackmailer he’d been forced to kill and that Wilson is laying a trap.

Rankin plots to kill Mary by beckoning her to the top of the church clock tower; the ladder has been booby-trapped. However, she is prevented from arriving by her housekeeper, and in her place Noah and Wilson are almost killed. Rankin goes into hiding and Mary unravels psychologically (there is an “impressionistic montage” or dream sequence). We return to the opening sequence: Mary crosses town at night, seeking to kill Rankin in his hideout in the clock tower. Wilson intervenes. During a gun battle, Rankin is impaled on a sword brandished by an angel statue in the gothic clock mechanism. He and the statue fall to the ground as a mob of the townsfolk gather at the foot of the church.28

* * *

A handwritten correction in Welles’s copy of the shooting script names the South American port city ‘Puerto Indio’, although the name is not mentioned in the final cut of the film. There are a few indications to suggest this fictional city is based on Buenos Aires, including a reference in the script to tango. Welles had visited that city in 1942 on his Good Will tour.29 In January 1945, Welles called for direct Allied involvement in Argentina’s affairs, due to the Nazi wealth invested in the country.30 Nazi influence in Argentina was topical: Edward Dmytryk’s Cornered (1945) cast Dick Powell as a Canadian war veteran hunting a Nazi in Argentina to avenge his wife’s death. That film created its Buenos Aires in Hollywood. Welles’s Puerto Indio is similarly a studio creation, and what survives is stunning. Later Welles described the South American section as “the only chance to be interesting visually in the story”.31

Following the incompletion of It’s All True, Welles indeed re-emerged with a Latin American story, but instead of an uplifting celebration of Pan-American unity, Welles created a dark and murderous South American port city devoid of the appealingly exotic. Puerto Indio is the end of a ratline for escaping Nazis. Here war criminals change their names and nationalities, and go underground.

The shooting script, while cut down from the more expansive Welles–Huston temporary draft, nevertheless covers more spaces of this imagined city than the final cut.32

After the S.S. Bolivar docks in Puerto Indio, an immigration official and ship’s purser check through a Romanian man, a Dutch woman, and Konrad Meinike (under the Polish passport of one ‘Stefan Podowski’). The mentally disturbed Meinike rehearses his explanation: “I am travelling for my health”. He is waved through the border check. The camera cranes up to Wilson observing from an overhead ramp. He confers with local agents Señor and Señora Marvales, who will trail Meinike through the city. During filming, Welles apparently extended the crane shot to take in Señora Marvales’s pursuit of Meinike beyond the border post, but the shot was pointlessly abridged in the release version by a clumsy slow dissolve. It is the only crane shot of this South American section to make the release version of the film, although several others are noted in the shooting script.

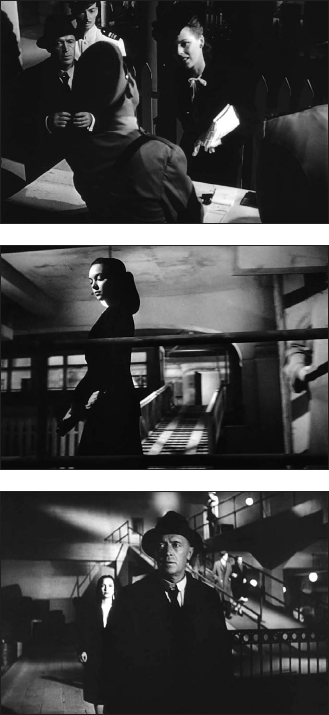

Three surviving frames of the abridged crane shot: Meinike at immigration, observed from above by Señora Marvales, and followed

As Meinike crosses a “rustic bridge” he is compared to a “small, scuttling spider”. Once again, Welles sketches a scheme to use diegetic music to help enhance the illusion of a city’s space. When Meinike passes the door of a “cheap nightclub” we hear a “slow, sad tango”. Further on, “through a group of archways”, Meinike passes another bar, where we hear “hot exciting rhythm played by a small, corny band” (only a murmur of Latin American dance music underlines this scene as it survives in the film, in shortened form).

All the while Meinike is under almost omniscient surveillance: the Marvales have access to private telephones in bizarrely convenient buildings around the city. The silhouette of Señor Marvales observes Meinike from a window as he telephones a report to Wilson at the Hotel Nacionale.

At this point the shooting script presents a number of powerfully evocative Puerto Indio scenes that did not make the final cut. The first setting is terrifying, even on the page: the Farbright Kennels, a warren of dog cages adjoining a multi-storey building. Fierce German police dogs are kept in order by a whip-brandishing trainer in a wire face mask. A vertiginous crane shot was to have moved from the dog cages to track up the side of the building, where Meinike observes from a ramp. He then ascends to the top of a circular staircase to meet Farbright, another Nazi fugitive. Meinike seeks the current whereabouts of Franz Kindler. Inside “a shabby room” at the top of the building, Farbright and a seedy doctor drug Meinike and interrogate him to confirm his loyalty. Farbright is sufficiently convinced to direct Meinike to a contact who will provide a new passport. Señora Marvales observes the meeting from ground level beside the cages. As the dogs growl, she can see light escape from the fringes of the burlap sack that covers the shabby room’s window.

At dawn Meinike continues along a “high rampart above the city” en route to collect his passport from a Nazi who works in a morgue. Señora Marvales reports Meinike’s whereabouts to Wilson from a telephone in a basement. Meinike reaches the morgue on a deserted street. A woman appears leading a goat and selling milk. In the earlier temporary draft, however, Meinike was to have seen instead the shadow of a crucifix fall on the street. He falls to his knees and interprets it as a message from God. His subsequent comment to his passport photographer – that he comes in the name of the “all highest” – was meant to play on the photographer’s confusion between God and the Führer, an irony lost by the time of the shooting script (in fact, many of the script’s religious references were cut by the time of the release version).33

Señor Marvales, again observing Meinike from yet another convenient window, makes a telephone report to Wilson; by now, however, Señora Marvales has gone missing. Inside the morgue, the Nazi hands Meinike his new passport (still lacking an identity photograph) in the name of ‘Phillipe Campo’. Before Meinike departs, “two bruisers”, including the sinister dog trainer from the Farbright Kennels, wheel in the corpse of Señora Marvales under a “rough cloth”. The audience will identify her by a distinctive golden hoop earring. She has been savaged by wild dogs.

Now Meinike proceeds to a photographer’s studio to complete the passport. The release version of the film resumes here, skipping the kennels and morgue scenes entirely. Considering the excision of the intervening scenes, it is entirely possible the dissolve from Señor Marvales’s initial report to the photographer’s studio scene was not designed by Welles. Nevertheless, the matching framing of the silhouette of Marvales and the shadowy photographer perfectly suits this city of fluid identities.

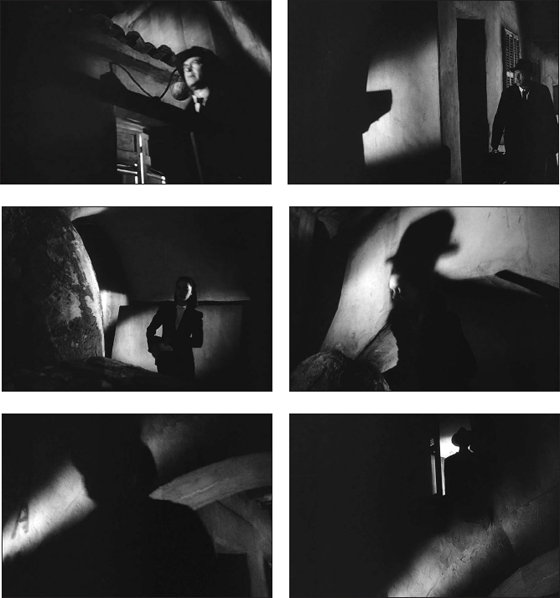

The dissolve from Señor Marvales to the passport photographer

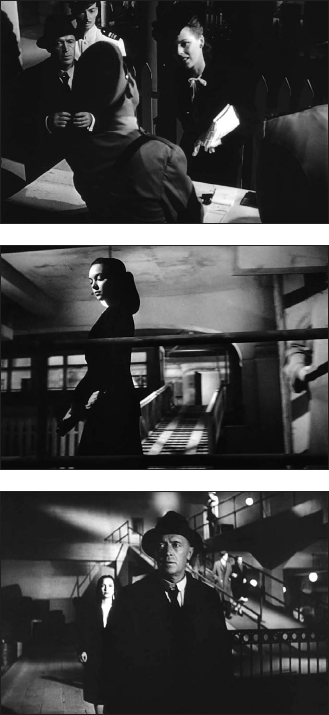

In the surviving three and a half minutes, Puerto Indio appears as a shadowy city of cavelike passages. The camera pans from low angles to follow Meinike and Señora Marvales in pursuit. Welles and cinematographer Russell Metty film silhouettes and Meinike’s monstrous shadow as it plays over rough walls. The pair would repeat this brilliantly expressionist use of shadows when they reunited for Touch of Evil.

* * *

Puerto Indio: city of silhouettes and shadows

The remainder of The Stranger takes place in the very different setting of Harper. Its pastoral qualities are established in the shooting script by the courtship of Rankin and Mary.34 “Let’s go through the fields,” he tells her at their first meeting. “It’s my favorite walk… It’s beautiful that way … through the cemetery, over the little brook and then the woods.” Rankin encourages her to cross the stream over a plank; in this way Mary temporarily overcomes her fear of heights (this scene was cut or possibly never filmed). Rankin will quickly pollute the town’s pastoral tranquillity by his murder and burial of Meinike in the woods.

Harper as postcard

The mythical smalltown setting with pastoral fringes had also featured in Huston and Veiller’s Killers script as Brentwood, New Jersey. But otherwise it was the rare setting of noirs such as Shadow of a Doubt (Alfred Hitchcock, 1943) and Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947). They all share narratives of murderous urban forces invading the peace of an idyllic small town. The Stranger, which uses the conceit in the context of a political rather than straightforward crime thriller, is surely inferior to each of these other films, but Welles is alone in introducing an ambiguous undertone to the small town setting.

He was not quite so eager to evoke the virtues of smalltown life as he had been four years earlier for Ambersons. Harper is a quirky but provincial town that has been too long closed to the sobering political urgencies of the world. In the shooting script (but cut from the film), the discovery of Meinike’s corpse prompts one of the baffled locals to wonder, “What would a South American … just off the boat … be doing in our incosmopolitan little town?”35

The broken clock crowning the church tower, found by the production at a Los Angeles museum,36 serves as both a plot point – repairing clocks is Rankin’s tell-tale hobby – and a flexible metaphor. In the shooting script, Rankin describes the “ideal social system in terms of a clock”.37 But it also represents the town’s stasis. When Rankin manages to repair the mechanism, one citizen complains, “Charles Rankin, I wish you’d left that clock alone. It was a nice quiet place until it began banging.” Mary’s naivety regarding the extremes of human depravity verges on a dangerous moral complacency. Even when Wilson confronts her with (real) documentary footage of a Nazi camp, Mary refuses to accept her husband’s true identity and moral responsibility for mass murder. She has a psychological breakdown.

* * *

Welles initially intended to construct the Harper town set from the plan overleaf at Twentieth Century Fox (the art director was Kane’s Perry Ferguson). That plan would have better established a concentrated sphere of action and a coherent spatial relationship between the film’s key settings – Potter’s drug store, the Harper Inn (where Wilson lodges), the church and cemetery bordering the woods, and the Rankin home.38 The centre of the town was intended to be the church and clock tower, which the shooting script describes as “fronting a green around which the township itself is clustered, cradled by the gentle slopes of the Berkshire foothills”.39

Welles had to compromise for budgetary reasons and shoot the film on the permanent Universal Studios smalltown set.40 Numerous other films had been shot there, and to moviegoers the familiarity of the town layout, based around a central square, would have only increased the mythical unreality of Harper. The town appears antiseptically clean with its polished gymnasium floors and its raked late autumn lawns. Once again Welles employs paper detritus to dress his setting: the high school boys’ paper chase through the woods, which almost leads to the accidental discovery of Meinike’s murder scene, temporarily litters the mise-en-scène. The shooting script has Rankin desperately tear pages from Meinike’s Bible to create an alternative trail leading away from the corpse. This audacious act of Bible destruction was abandoned when the film was shot.

The original plan for the Harper town set Courtesy, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

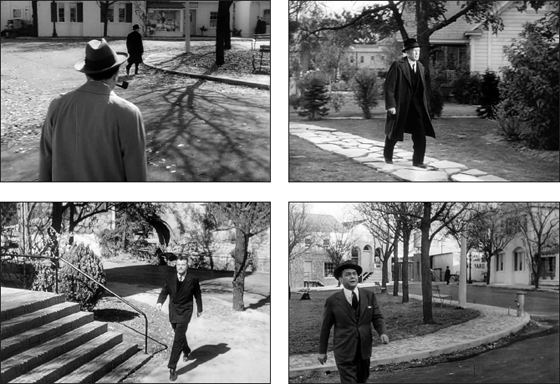

Welles’s camera was becoming increasingly mobile, at least while he still had access to Hollywood’s ace technicians. There are many tracking shots of characters navigating Harper by foot, which emphasises its smalltown compactness, although the coherence of the spatial relationships between the settings beyond the central square was lost owing to the abandonment of the original town plan.41

Walking through Harper

* * *

Like Puerto Indio, Harper is dominated by surveillance. The shooting script repeatedly describes the act of looking. In a comment anticipating a more famous line in The Third Man, Rankin looks down from the clock tower on the mob and says he feels “like God looking at little ants”.42 Often the gaze is cast through obscuring windows. In a shot described in the script that didn’t make the final cut, Meinike hides from Wilson in the doorway of a store, behind the “plate glass windows” that “angle gently out from the deeply recessed entrance… He is able to look out through the glass cases and thus can observe the street without being seen.”43 The looking-through-windows motif was realised mostly in shots set in the vicinity of Potter’s Drugstore.

The act of looking in Harper

Potter’s Drugstore is both the nexus of social activity – it doubles as the town’s bus stop – and the central place of observation. Welles installed signs in his own handwriting, including “Gentlemen! Do Not Deface Walls!” (Potter is less passive-aggressive than the blind shopkeeper in Touch of Evil, whose sign warns “If you are mean enough to steal from the blind, help yourself”).44 The script describes Mr Potter as “an immensely fat New Englander, whose philosophy permits but one form of exercise – the punching of a cash register”.45 Potter is so lazy he insists his customers find their own items on the shelves and fill their own coffee cups, a novelty in those days. As portrayed by Billy House, the character enlivens the otherwise dull dramatis personae with a spark of Welles’s absurdist but homespun humour. Not as crafty as he imagines himself, Potter is the local gossip and ‘town clerk’, and, as he tells Wilson, “Town clerk runs the town, you might say.”46

Welles would never again return to so homespun a background as Harper. Political urgencies took him forever away from Main Street, USA.