There was no attempt to approximate reality; the film’s entire ‘world’ being the director’s invention.

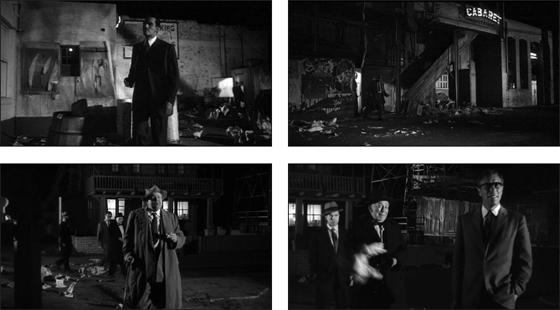

Quinlan’s entourage: Representatives of U.S. law in Mexican territory

Touch of Evil, made during Welles’s two-year return to the United States after nearly a decade in Europe, was the (almost) triumphant culmination of Welles’s anti-fascist Pan-American thrillers. After two independent Pan-European films (Othello and Mr. Arkadin) and various British and American television projects, all of which demanded the invention of radical low-budget methods, Welles returned one final time to the relatively ample financial and technical facilities of a Hollywood studio. He exploited these resources to create ‘Los Robles’, a stunning noir city filmed in the streets of Venice Beach, Los Angeles.

Touch of Evil expresses a number of Welles’s political concerns, most obviously the racial discrimination against Mexicans inside the American policing and legal system. It was a long-term concern: back in 1942 Welles had joined the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee to defend falsely accused Mexican-American youths in a notorious California trial.2 Mike O’Hara’s dislike of the police in The Lady from Shanghai had been a stance of revolutionary anti-authoritarianism; Touch of Evil centred its drama on the racism, corruption, and violence of a police captain and his entrenched position within the legal bureaucracy.

Another palpable political context of Touch of Evil is Welles’s hostility not just to nationalism, which he had long argued was the seed of fascism, but more radically to the bureaucratic accoutrements of the modern nation state (which included the police). In 1955 Welles had filmed a monologue for the UK’s BBC television on the subject of ‘The Police’. He began by recalling his involvement in the Isaac Woodard case, and went on to say:

I’m willing to admit that the policeman has a difficult job … but it’s the essence of our society that the policeman’s job should be hard. He’s there to protect the free citizen, not to chase criminals. That’s an incidental part of his job. The free citizen is always more of a nuisance to the police than the criminal. He knows what to do about the criminal.

Welles also denounced customs officials, the necessity of passports, “red tapism and bureaucracy, particularly as it applies to freedom of movement”. “[Travel is not what it was in] our fathers’ day”, before passports, because now “we’re treated like demented or delinquent children and the eyes are always on us.” He told an anecdote about a European experience in which he sarcastically informed humourless police inspectors he was carrying an atomic bomb in his bag.

Welles lumped police and bureaucrats together as “one great big monstrous thing” and said

the bureaucrat is really like a blackmailer. You can never pay him off. The more you give him, the more he’ll demand… I’m not an anarchist, I don’t want to overthrow the rule of law. On the contrary, I want to bring the policeman to law.

Welles’s sketches of his European police encounter in Orson Welles’ Sketchbook (1955)

Welles suggested the formation of the International Association for the Protection of the Individual Against Officialdom. “If any such outfit is ever organized, you can put me down as a charter member.”3

In his 1950s work Welles frequently mocked the modern nation state itself as a political fiction. Mr. Arkadin and his television documentaries frequently expressed saudade for antiquated cultural unities – the Austro-Hungarian Empire and interwar Eastern Europe – now obliterated and divided by the postwar political order. In his television series Around the World with Orson Welles, he celebrated Pentecost because it was the one day of the year when the border dividing the ancient Basque country between Spain and France was open to free human passage. Welles goes on to say:

It’s not only the Basques. Nobody really likes an international border. The nations it divides always want to push the border back a bit in their favor, and I rather think the people it divides would just as soon do away with it altogether.4

Touch of Evil provided Welles with the opportunity to explore the cinematic possibilities of a border setting in the Americas after reimagining the American small town and the Pan-American port city in his mid-1940s noirs. Only a few contemporary thrillers had used the border setting, including Anthony Mann’s Border Incident (1948). Touch of Evil particularises Welles’s political insights into the operation of power on the border, and illustrates the ways racism thrives in such an ideologically divided space. A racist American detective’s long-term abuse of his position has been protected by a network of institutional, personal, and criminal associates on both sides of arbitrarily divided Los Robles, as well as by the myths of his investigative ‘intuition’ and self-sacrifice for the law. The arrival of a conflicting liberal and international vision of law leads to the detective’s downfall. The film frequently upsets the clichés of the 1950s police procedural.

In any of the several versions of Touch of Evil, Los Robles is Welles’s most palpably realised cinematic city; in his original conception, it would have been the culmination of the director’s career-long innovations in mise-en-scène, mobile tracking shots, editing, and sound. Moreover, Welles uses the spaces of the cinematic city itself to illustrate his ideas.

In the tradition of leftist spatial theory, Iván Zatz offers a political reading of how power is enforced in the “abstract space” of Welles’s Los Robles, which is “not broken by any natural or physically obvious obstacle, [but] by the sheer presence of authority”. He writes:

Inequality would be a lot harder to maintain without the protected and policed exclusivity of fenced communities – borders, as this film makes clear […] Space, at this level, can be said to be abstracted precisely because there is no reason, other than an ideologically constructed one, to divide this space [with the border except] in order to prevent a natural movement of human beings through it.5

* * *

There are several contradictory accounts of how Welles was promoted from supporting actor to the job of rewriting and directing Touch of Evil, which was produced by Albert Zugsmith for Universal Pictures. The lead actor, Charlton Heston, supported Welles’s employment as director. Welles had performed a supporting role in Zugsmith’s similarly themed contemporary western The Man in the Shadow (Jack Arnold, 1957), and Zugsmith later claimed that Welles had offered to rewrite and direct Zugsmith’s worst story property.6

The source was the 1956 novel Badge of Evil by ‘Whit Masterson’, a joint pseudonym for Robert Wade and William Miller. A first-draft screenplay was written by Paul Monash before Welles signed on. In a short time Welles completely rewrote the Monash script and drew additional material from the source novel. Welles’s shooting script is further proof of his exemplary talent at reconceiving and personalising existing material. He altered the setting and the races of various characters to upset conventions, and reset the film on the tense American-Mexican border.7

Touch of Evil dramatises the exposure and death of Hank Quinlan (Welles), the corrupt Los Robles police detective. The trigger for his downfall is the investigation of the assassination by car bomb of local businessman Rudy Linnekar and a striptease dancer, Zita. Quinlan is discovered planting evidence in a suspect’s apartment by Ramon Miguel ‘Mike’ Vargas (Charlton Heston), a high-ranking Mexican narcotics official engaged in the prosecution of the criminal Grandi family in Mexico City. Vargas attempts to find evidence that will convince the local American authorities to bring Quinlan to justice. Meanwhile Quinlan, slipping back into alcoholism, agrees to conspire with the local Grandi boss, ‘Uncle Joe’ (Akim Tamiroff), to smear the reputation of Vargas and his American wife, Susan (Janet Leigh), by framing them in a drug conspiracy. The Grandi gang attack Susan at the Mirador Motel in the desert, (probably) sexually assault her, and leave her drugged in a skid row hotel room as a gift to the vice squad. Quinlan murders Uncle Joe at the skid row hotel to cover his tracks and sits out an alcoholic bender at a brothel run by a woman called Tana (Marlene Dietrich) on the Mexican side of the border. When Quinlan’s partner, Menzies (Joseph Calleia), discovers Quinlan’s cane at the Grandi murder scene, he goes to Vargas, who convinces him to secretly record Quinlan’s confession. Discovering the wire, Quinlan shoots Menzies; ailing, Menzies shoots Quinlan to protect Vargas. Quinlan falls into the river and dies.

Once again, the studio removed Welles from oversight of the editing and sound mix. After his departure in July 1957, additional expository or replacement scenes were directed by Harry Keller; they are inferior in every way to Welles’s material. Welles was shown a rough cut in early December, and immediately wrote a long memo to studio executive Edward Muhl suggesting improvements in editing and sound.8 Only some of his suggestions were adopted for a version of 108 minutes that was previewed in January 1958.9 The 95-minute film as released in February was an abridged version of that preview cut and lost several dramatically essential scenes, rendering other parts confusing.10

* * *

Los Robles is improbably advertised within the film on a billboard as the ‘Paris of the Border’. Much of the film was actually shot around the intersection of Windward Avenue and Pacific Street in Venice Beach, a suburb of Los Angeles that had been originally designed to evoke the Italian namesake.11 Venice was distinguished by streets lined by colonnades; Welles would use them as the architectural centrepiece of his invented border town. In addition to an installed border post, there are numerous shop signs in both English and Spanish, as well as masses of paper detritus, particularly in the area surrounding Grandi’s Rancho Grande, the striptease nightclub: frayed bilingual bill posters for stripteases, fights, and corridas; cardboard cut-outs of strippers; garbage and old newssheets billowing around the streets.

Touch of Evil revives the ambulatory mobility Welles had featured in The Stranger and The Lady from Shanghai. Propelling characters around the streets by foot, Welles maps this border area with his roving camera. In the 1960s Welles said, “I believe, thinking about my films, that they are based not so much on pursuit as on a search. If we are looking for something, the labyrinth is the most favorable location for the search.”12 Welles had intentionally created labyrinthine spaces in The Lady from Shanghai’s hall-of-mirrors sequence, and would later do the same for the dreamlike city of The Trial. It’s also true that as early as Othello he had ceased to prioritise the spatial continuity expected by Hollywood and enforced by conventional filming and editing practices. Close study of Welles’s editing – in those few films up to this point whose final form he was able to control – shows how frequently he flouted those conventions. Nevertheless, it is a simplification to categorise the spatiality of Los Robles as another noirish labyrinth, as have many past critical studies of Touch of Evil.

Although the cities of classic film noir are varied, they are nevertheless frequently described as labyrinthine cityscapes that mirror the unfathomable interpersonal relations of the population as well as the protagonist’s psychological disorientation and confusion.13 The interpretation puts the film noir firmly in the tradition of the classic German Expressionist film, examples including Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922). Clearly that tradition was important to the development of the visual language of film noir, not least due to the flight of directors such as Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, and Robert Siodmak from Nazi Germany to Hollywood. And yet the typically supernatural or fantastic settings of the German Expressionist films of the early 1920s differ from the settings typical of film noir, which has much more in common with the slightly later German Kammerspiel (‘chamber drama’) and street film.14 As Siegfried Kracauer defined it, this hybrid movement, like traditional Expressionism, “manages to transform ‘material objects into emotional ornaments,’ illuminate ‘interior landscapes,’ and emphasize ‘the irrational events of instinctive life’” while staying within a “plausibly realistic representational format”.15 Examples of the Kammerspiel include Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, F. W. Murnau, 1924), Varieté (Variety, Ewald André Dupont, 1925), and Der blaue Engel (The Blue Angel, Josef von Sternberg, 1930). The street films include Die Straße (The Street, Karl Grune, 1923) and Asphalt (Joe May, 1929). This approach was defined as ‘functional expressionism’ by critic John D. Barlow.16

Film noir’s varied attempts to reconcile expressionism with street-bound realism make the labyrinth a too-reductive spatial model for many cities in the noir canon. The early private-detective-centred noirs, adaptations from the hardboiled genre for which Dashiell Hammett had set the template, are really narratives about mastering the city through the successful navigation of public and private spaces, and the discovery and exposure of its complicated hierarchies of legal and criminal power. Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, the street-smart protagonists of The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and Murder, My Sweet (Edward Dmytryk, 1944) serve as cartographers of the city’s secret spaces. Even if the plot of The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946) is notoriously difficult to follow – even labyrinthine – Philip Marlowe does not have trouble finding his way around Los Angeles.

Then there are the cinematic cities of pseudo-documentary police procedurals like The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948), He Walked by Night (Alfred L. Werker, 1948), The Street with No Name (William Keighley, 1948), and Side Street (Anthony Mann, 1950). In these films, innovative ‘scientific’ methods of crime fighting allow the police to resume control over a wayward city. These films regularly attempt synoptic overviews of urban space. A typical component of the opening sequences are aerial shots of the cityscape. The Street with No Name features maps that monitor and pin down the routine movements of a criminal suspect.17 The opening narration by a police officer in Side Street brings narrative order to the diversity of human activity presented on screen and moreover instructs the audience to interpret those images in a fundamentally reactionary way.18

The labyrinth model is most applicable to the cities of those noirs of the immediate postwar period, which, in Dennis Broe’s expression, centred on an ‘outside-the-law fugitive protagonist’. Only the fun house and hall of mirrors really qualify as labyrinthine spaces in Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai, but many other film noirs of that period reimagine the city as a bewildering maze-like space for ensnared everyman protagonists, and adopt the protagonist’s point of view as he is persecuted by duplicitous women, criminals, the rich, or the authorities. Whereas Dassin’s Naked City emphasises the police’s synoptic mastery of New York City, his Night and the City (1950), set in postwar London, has been described as its “flipside … with overheated lighting patterns, bizarre angles, and claustrophobic compositions replacing the more methodical, unhurried organization of the earlier film”.19

Los Robles has been consistently lumped in with other noir labyrinths as a spatially incoherent, disorientating space. A key influence on this interpretation seems to have been the film’s mobile deep-focus cinematography. Welles and Russell Metty used lenses with focal lengths as short as 18.5mm; certainly the wide-angle distortion in some facial close-ups allowed the intrusion of the grotesque.20 Although Welles’s long opening crane shot fluidly tracks the passage of its characters through the border zone from Mexico into the United States, its cinematography and the busy choreography of the human crowd have often been categorised as disorientating. The frequently republished essay of one critic deems the mobile opening shot “less concerned with monitoring the events on screen than in disorientating the spectator”; it is a shot with “no mimetic function”; there is “too much information to pick and sort into stable hierarchies of attention”; the long shot is “a dance in which we lose our bearings … a whirling labyrinth” that produces “anxiety” born of “too much freedom”.21 The distortions of wide-angle photography notwithstanding, this reading seems a bizarre over-reach for a smoothly executed crane shot moving along two streets that form a right angle towards the clear destination of the border post.

Another factor in the designation of Los Robles as a labyrinth was the editing of the 1958 release version and the longer preview version rediscovered and screened from 1975. Early critics criticised the confusing editing, citing the difficulties in following the spatial position of characters on either side of the border.22

But much of the famous December 1957 memo of fifty-eight pages in response to the studio’s rough cut supports the theory that Welles intended to present the border city not as a disorientating labyrinth at all but as a geographically coherent space – expressionist, baroque, and grotesque though it may have been. The release and preview versions muddied Welles’s editing preferences, and blunted the effectiveness of his attempt to illustrate the networks of power that thrive in the spaces of the politically divided city, as well as the social networks and legal institutions that have allowed the corrupt Quinlan to thrive.

* * *

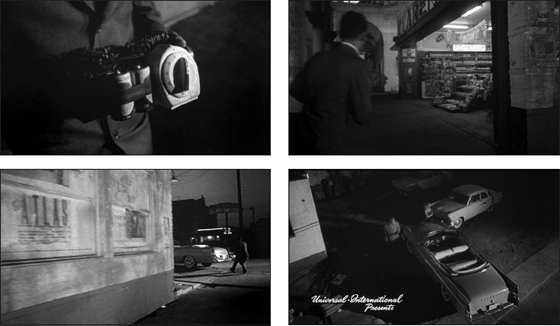

The opening shot brilliantly establishes the film’s key staging location on the Mexican side of the border. It is a deep-focus tracking shot of three minutes and twenty seconds. The shot follows the planting of a time bomb in a convertible before it moves from the parking lot of a Mexican strip club to its obliteration just inside the United States. The first half-hour of the film is set in this vicinity, on both sides of the border, from late night until dawn.

The shot begins with an assassin setting the time bomb on a main street lined with colonnades. From a distance the assassin watches Linnekar and Zita leave the front door of a nightclub. We later discover the club is owned by ‘Uncle Joe’ Grandi and is called Grandi’s Rancho Grande. “Kind of a joke,” Uncle Joe later explains to Susan (the Grandis are apparently ancestrally Italian, not Mexican, and live on both sides of the border). The assassin runs to plant the bomb in the trunk of Linnekar’s convertible, parked near the side entrance of the nightclub, behind the Clarence liquor store.

Planting the bomb

Almost opposite the Clarence liquor store is the St Marks Hotel, honeymoon rendezvous for Mike and Susan Vargas. We later discover that the Vargases are staying in a first-floor room above the intersection of the main street with a narrow one-way lane.

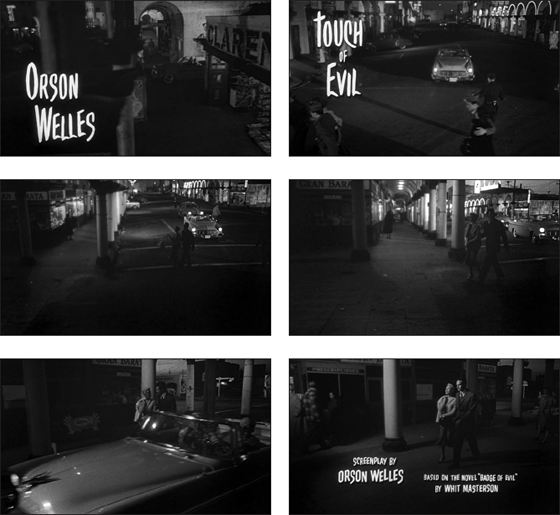

Linnekar drives off with Zita. The camera tracks backwards ahead of the car as it drives along the main street for one block in a westerly direction. The car crawls through police-directed pedestrian traffic (and past such oddities as a cart selling sombreros) and makes a perpendicular right-hand turn onto another street that leads directly to the border checkpoint. At the corner the camera switches allegiance to anticipate the path of the Vargases, who are making a leisurely ambulatory passage towards the border, “hot on the trail of a chocolate soda”.

The doomed car comes within the Vargas’s vicinity several times as it weaves through the pedestrian, automobile, and livestock traffic. It moves away as the Vargases cross the border into the United States. Their kiss on Susan’s side of the border is interrupted by the sound of the car exploding.

Movement to the border checkpoint

The soundtrack on the original 1958 release print was not approved by Welles. He planned another version of the sound scheme which went back to Heart of Darkness.23 The December memo explains:

As the camera moves through the streets of the Mexican border town, the plan was to feature a succession of different and contrasting Latin American musical numbers – the effect, that is, of our passing one cabaret orchestra after another. In honky-tonk districts on the border, loudspeakers are over the entrance of every joint, large or small, each blasting out its own tune by way of a ‘come-on’ or ‘pitch’ for the tourists. The fact that the streets are invariably loud with this music was planned as a basic device throughout the entire picture.24

The soundtrack of this sequence in Touch of Evil was remixed for the 1998 restoration along these lines.25 It is dramatically effective in several ways. It emphasises the suspense of the scene; the distinctive rock and roll from the convertible’s radio fades in and out as the rigged car approaches and moves away from the Vargas couple. The soundtrack as mixed in the preview and theatrical release versions, with its excellent but overwhelming Henry Mancini non-diegetic score and superimposed title credits, makes it easier to forget about the bomb in the Linnekar car.26 Welles’s sound scheme complements the roving crane shot with a matching aural component. Each element is designed to envelop the audience in the space of the border city.

The opening shot ends with the sound of the explosion of the Linnekar car just inside US territory, followed by a cut to the flaming car leaping in the air. The next shot is slightly spatially inconsistent, because the Vargases are now further away from the border checkpoint, in the area in front of the Paradise Dance Hall.

At Mike’s request, Susie re-crosses into Mexico to wait at the St Marks Hotel. She is followed across the border by the young Mexican she will come to nickname ‘Pancho’ (Valentin de Vargas); however, an abrupt cut from the entrance of the Paradise Dance Hall in the United States to a Mexican street skips any depiction of Susan and Pancho’s actual border-crossing, which no doubt adds to the spatial confusion. However, responsibility for this particular cut cannot necessarily be attributed to Welles; it may well have been part of the studio’s reworking of the separate adventures of Mike and Susie after the explosion, a section of the film with which Welles was particularly unhappy because the studio altered his pattern of crosscutting. Susie is accosted by Pancho and invited to receive something for her husband. Pancho leads her back into the United States. “Across the border again?” she asks.

The next time we see Susan she arrives with Pancho at another key staging location in the film’s geography, a skid row hotel named the Ritz, an American counterpart to the Mexican Grandi’s Rancho Grande/St Marks Hotel intersection. The Ritz is a few doors up from a neon crucifix (“Jesus Saves”) and across the street from the Grande Hotel – Grande and Grandi are everywhere on both sides of the border. Uncle Joe has a kind of headquarters in the ground floor lobby of the Ritz. An upstairs room of the hotel is later the scene of Grandi’s murder by Quinlan.

When the grotesquely obese Quinlan arrives at the bomb site, he exercises complete authority over the investigation. Police Chief Gould (Harry Shannon) seems totally at Quinlan’s command, confused perhaps by Quinlan’s methods (“you don’t even want to question the daughter?”) but always acquiescent. This sequence, built out of a series of close-ups and medium shots around the smoking and flaming car, expertly establishes Quinlan’s entrenched and protected position in the legal and investigative network of Los Robles. Quinlan has protected his position by promoting his own myth as a crime solver. The district attorney, Adair (Ray Collins), refers to Quinlan as “our local police celebrity” and later “one of the most respected police officers in the country”. Quinlan demonstrates a joking and even condescending acquaintance with Adair, who is dressed up in a “monkey suit” for a banquet.

Quinlan’s fraudulent success as a detective is sustained by the broad acceptance of his myth by the legal authorities of Los Robles.27 Vargas is quickly introduced to the myth of Quinlan’s ‘intuition’. Quinlan senses immediately the bomb was dynamite because of his “game leg”. “Sometimes he gets a kind of twinge,” says Menzies with an admiring grin, “like folks do for a change of weather. ‘Intuition’, he calls it.” Quinlan smiles benevolently at the propagation of the myth. Menzies later confides to Vargas that Quinlan’s leg was wounded by a bullet meant for him; it makes Menzies’s final betrayal of Quinlan all the more emotionally difficult.

Hobbling on his cane, Quinlan leads Menzies and an entourage of American legal representatives across the border into Mexican territory, retracing in reverse the path of the rigged convertible back to Grandi’s Rancho Grande. The entourage consists of District Attorney Adair, Al Schwartz (Mort Mills) (from the DA’s office), Chief Gould, and Blaine (some kind of American official who already knows Vargas). This flouting of police procedure, an investigation outside American jurisdiction, continues despite the DA’s weak protests. The sequence also reaffirms the Grandi’s Rancho Grande/St Marks Hotel intersection as a key area in the city’s geography.

Vargas is momentarily distracted at the hotel by his reunion with Susie and her tale of near-abduction by Pancho (the weak expository scene in the preview and release versions was actually directed by Harry Keller). He lags behind Quinlan’s entourage as they head into the side entrance of Grandi’s Rancho Grande to question the strippers. Risto (Lalo Rios), a young member of the Grandi family, trails Vargas from the St Marks. Vargas strides purposefully and Risto’s distorted shadow leaps across the poster-papered exterior walls of the nightclub – the same expressionism-within-realism lighting technique cinematographer Russell Metty and Welles had pursued more than ten years earlier in the Puerto Indio sequence of The Stranger (Welles had also used a similar technique in Othello and Mr. Arkadin).

Expressionist wall shadows in The Stranger (L) and Touch of Evil (R)

Risto hisses Vargas’s name and attempts to hurl a glass bottle of acid into his face; the acid misses Vargas and destroys a poster advertising performances by the ever-unfortunate Zita. This acid attack occurs approximately at the site of the bomb planting.

After Quinlan and his entourage fruitlessly question Zita’s co-workers, they emerge from the nightclub’s back entrance. Oil derricks tower in the dawning sky. The space is filled with the paper detritus of newspapers and garbage.

Early critic Eric M. Krueger described Los Robles as “a world where filth, garbage, and disarray become metaphors for evil – swirling in the funhouse, the dream, and the delirium”.28 The transformed Venice Beach, filled with the realistic detritus of daily urban human activity, allows Welles to again introduce expressionism into an ostensibly realistic setting.

Garbage around Grandi’s Rancho Grande and Tana’s brothel

Quinlan finds himself near a brothel and its siren call of pianola music. Quinlan goes inside to renew his old acquaintance with the madam, Tana, who doesn’t recognise him in his obese state. Quinlan jokes about returning to sample Tana’s chilli – “maybe too hot for you”, she warns. This echoes a jokey comment made by the district attorney cut from the theatrical release version. Quinlan’s past patronage of the brothel seems to be an agreeable part of his personal mythology in the legal hierarchy.

Again outside Tana’s brothel, confronted by Vargas’s earnest distress over his wife’s near-abduction by the Grandis, Quinlan makes insinuations about Mrs Vargas’s sexual morals; at Adair’s defensive and uneasy joke that Quinlan is a “born lawyer”, the detective insists: “Lawyer! I’m no lawyer. All a lawyer cares about is the law.” In response to Vargas’s earnest insistence about law enforcement – “A policeman’s job is only easy in a police state. That’s the whole point, captain. Who’s the boss, the cop or the law?” – Quinlan defines his job bluntly: “When a murderer’s loose, I’m supposed to catch him.”

To Iván Zatz, the Mexican Vargas and American Jew Schwartz are “transnational technocrats” who overcome the jurisdictional challenges of an ideologically divided space to impose international, United Nations-style justice and defeat Quinlan’s corruption.29 Vargas introduces himself to Quinlan as “what the United Nations would merely call an observer”, but he quickly angles for a stronger role on US soil in the name of justice. International governance remained Welles’s preferred antidote to fascism.

As the night wears on towards a grim dawn, Pancho harasses Susie in her hotel room by shining a flashlight on her from a window across the way. Soon Risto, who threw acid at Vargas on his own initiative, is chased by Uncle Joe and Sal (another Grandi nephew) from the intersection outside the St Marks across the street to the parking lot beside and behind Grandi’s Rancho Grande. During this chase the camera angles are canted, and spatial coherence is momentarily disjointed; also, improbably, the sands of Venice Beach seem to be glimpsed for a moment during the scuffle.

By the conclusion of the film’s opening act, Quinlan’s deeply entrenched position in the legal and social structure of Los Robles is established. Quinlan’s habit of planting evidence will soon be discovered by Vargas during the investigation of the car bomb, but Vargas’s insistent attempts to bring Quinlan to justice have to break through the defensive clique of local legal and police authorities, with their mythical narratives of Quinlan’s past exploits, and finally Quinlan’s employment of his criminal associate Uncle Joe Grandi. In the best version, the 1998 edition, Touch of Evil is a stunning product of Welles’s career-long cinematic innovations in service of his mature insights into the operation of power in an American border city.

NOTES