I am, have been, and will be only one thing – an American.

– Charles Foster Kane

I do not know who I am.

– Gregory Arkadin

Through the 1950s and 1960s Welles was intensely interested in the operation of power, the problems of nationalism, and the meanings of freedom and justice in Europe. For a time Welles claimed to be writing a book on international government, possibly a collaboration with Louis Dolivet.1 Although the book never materialised, his current political ideas found their idiosyncratic way into Mr. Arkadin, which was Pan-European in both its themes and its innovative mode of production. Any sort of coherence was lost, however, because once again Welles was unable to complete editing the film. It finally emerged in a set of bizarre variations seen by a limited audience.

The production of Arkadin began without a conventionally rigid shooting schedule and budget. Filming began in January 1954 and continued far beyond expectations, requiring Dolivet to repeatedly seek new funds. The production used Sevilla Film Studios in Madrid and locations in other parts of Spain, on the French Riviera, in Munich (on location and at Bavaria Studios), and in Paris (on location and at Photosonar studios in Courbevoie). Many of these locations doubled for international settings from Tangier to Acapulco.2 Welles had shot and edited what became the largely self-financed Othello on two continents over a period of more than three years; on Arkadin he seems to have shifted his approach during filming towards the same multi-national patchwork method. This time he failed to find satisfaction. Welles remembered the shoot as “just anguish from beginning to end”.3 He and Dolivet quickly realised they were not suited to working together in the film business and agreed to wind up their joint business ventures after the completion of Arkadin.4

Even before all the necessary footage had been shot, a Spanish-language version of Mr. Arkadin had been assembled by August 1954 for finance-raising purposes. Presumably to qualify for the advantages of Spanish co-production status, two Spanish actresses, Amparo Rivelles and Irene López Heredia, gave performances that were later replaced in non-Spanish versions by Suzanne Flon and Katina Paxinou, respectively. Welles missed a September 1954 deadline to complete the English-language version of the film for a premiere at the Venice Film Festival; sporadic shooting was still going on in France as late as October.5 A major falling out between Welles and Dolivet over the prolonged editing process – according to editor Renzo Lucidi, Welles was locking in a mere two minutes per week6 – led to Welles’s departure in January 1955. The editing continued under Lucidi, with some external input from Welles, who planned to return to make a final revision; as it turned out, he did not participate further. Even under these strained conditions, Filmorsa continued to work with Welles and insist he honour his exclusive contract. The company funded test material for Don Quixote in Paris and worked alongside a British company, Associated-Rediffusion, to produce Welles’s documentary series Around the World with Orson Welles for ITV television. Welles eventually broke his contracts and returned to the United States in October 1955. He left behind incomplete film materials for only seven of the planned twenty-six episodes of Around the World.7

A lost English-language version of Mr. Arkadin, titled Confidential Report, had premiered in London in August 1955.8 Another, probably slightly different, version – also now vanished – went into general release in the United Kingdom in November.9 There are at least two surviving Spanish-language versions featuring Rivelles and López Heredia: one that strangely misattributes Robert Arden’s performance to ‘Mark Sharpe’ and a later shorter version – the official Spanish release – which miscredits him as ‘Bob Harden’.10 A revised English-language version, also called Confidential Report, was released by Warner Bros. in Europe in the spring of 1956. This version has also survived. By this version much of the flashback structure, framed by a conversation between the characters Guy Van Stratten and Jakob Zouk, had been altered.11

In the very early 1960s the young American director Peter Bogdanovich investigated the holdings of a Hollywood television syndication company, M. & A. Alexander, and discovered a version of Mr. Arkadin that would become known as the ‘Corinth’ version, an early edit of mysterious origin that retained the flashback structure. Another US version, a crude reassembly in chronological order, lapsed into the public domain and for a long period was the most accessible version to the American public.12

The film (in its numerous variant versions) was not commercially or critically successful. The deep friendship of Welles and Dolivet may not have been irretrievably destroyed by the failure of the project, but for the following period their relationship was tumultuous. In 1958 Filmorsa unsuccessfully sued Welles for his behaviour during the production.13

As with many Welles films, determining what is the director’s own work and what was compromised or reworked by the producer is difficult. Moreover, only some of Mr. Arkadin’s many variant versions are easily accessible. The three versions readily available are the ‘Corinth’, the 1956 European Confidential Report, and a posthumously assembled hybrid version called the ‘Comprehensive Version’, the work of Stefan Drössler of the Filmmuseum München and Claude Bertemes of the Luxembourg Cinémathèque.14

To add a little more to the elusiveness of a definitive Arkadin, there were also two versions published as prose fiction, both attributed to Welles’s authorship. An obscure, very short, and not particularly effective five-part serial appeared in consecutive August 1955 issues of the UK’s Daily Express to promote the film. The French novelisation, Monsieur Arkadin, serialised in France-Soir and published in book form by Gallimard in 1955, was attributed to Welles but actually ghostwritten by his French associate Maurice Bessy. The French novelisation was anonymously translated into English and published in the United States and United Kingdom in 1956 under Welles’s name.15 These publishing projects, like Bessy’s earlier French novelisation of Welles’s unmade script V.I.P. as Une Grosse Légume (1953), were part of Filmorsa’s scheme to raise money for its doomed ventures.16

* * *

Mr. Arkadin had a complicated genesis. It’s titular tycoon character led it to be compared unfavourably to Citizen Kane – a European self-parody or inferior knock-off, as John Huston’s Beat the Devil (1953) was to his The Maltese Falcon. But Arkadin is actually a distant cousin – or bastard step-nephew – of the very successful Third Man and is positioned within the generic lineage of the serious thriller, albeit in often bafflingly idiosyncratic and not particularly serious ways. Perhaps this tangential connection to a commercially successful property led Welles to claim in retrospect, rather bizarrely, that Arkadin had had the potential to be “a very popular film, a commercial film that everyone would have liked”.17 Things didn’t work out that way. During post-production, Welles said, “it pretends to be a thriller – and it isn’t”.18

The Third Man had revived the serious thriller in the political context of postwar Europe. Graham Greene wrote it as a novella in preparation for his screenplay. Welles filmed the bulk of his performance as Harry Lime in Vienna in late 1948 as he scouted locations and made test shots for Othello.19 The Third Man’s commercial and critical success made Welles even more famous, particularly in Europe.

The setting of The Third Man is the rubblescape of postwar Vienna, demarcated into zones by the Allied forces. The American Harry Lime, apparently dead at the outset, turns out to be a remorseless dealer in black market penicillin. His naive American friend Rollo Martin is confronted by his friend’s ruthless criminality and sudden reappearance. The film ends with a famous chase through the sewers of Vienna. The expressionist cinematography of Robert Krasker – high-contrast, deep-focus black and white – is one of the reasons the film is often mistaken as the directorial work of Welles himself.

The Lives of Harry Lime (1951–52), a British radio prequel series, was ingeniously produced by Harry Alan Towers – “a famous crook”, Welles recalled20 – without the participation of the film’s original producer, Alexander Korda, or director, Carol Reed. Towers separately secured Welles as an actor (and inevitably director and occasional writer) as well as the rights to use Greene’s character and Anton Karas’s ‘Third Man Theme’ for zither. Harry Lime’s criminal psychopathy was toned down. The cosmopolitan settings – Europe, North Africa, India – could be achieved rather more economically on radio than on film. The episodes were pre-recorded, largely at Welles’s convenience, in London, Rome, and Paris.21

Welles later said the Arkadin screenplay was created “from just throwing together a lot of bad radio scripts”.22 The film’s central plot is drawn from one of Welles’s Harry Lime episodes. ‘Man of Mystery’, the key episode that introduces Gregory Arkadian (note the slightly different spelling) and the investigation of his past, was recorded in Paris in 1951 and first broadcast on 11 April 1952.23 However, a Milan film magazine had reported some conception of Arkadin as a film screenplay (under its working title, Masquerade) already underway in March 1951 while Welles was in Casablanca shooting more of Othello.24

‘Man of Mystery’ introduces Arkadian as “one of the richest men in Europe”. He has never been photographed. Arkadian wants the contract to build airbases in Portugal for what is implied to be NATO. Welles may have been inspired by the US-Portugal Defense Agreement, signed 6 September 1951, which codified US military rights to an airbase on the island of Lajes in the Azores.25 Arkadian knows he will be subject to a thorough intelligence check by the United States Army. He hires Harry Lime, with his knowledge of the “continental underworld”, to prepare an advance report on Arkadian’s past. Arkadian claims he suffers from amnesia, remembering nothing prior to the winter of 1927, when he found himself in Lucerne possessing “only the suit I was wearing and a wallet with two hundred thousand francs… Swiss francs. It was with that money that my present great fortune was built.” Lime investigates, discovers Arkadian had come to Switzerland from Warsaw, and decides to “look up a few Poles” now dispersed over the world. During Lime’s interviews it emerges that Arkadian is really Akim Athabadze, a former member of a ‘white slavery’ and dope smuggling gang in interwar Poland. Closely tracking Lime’s investigation, Arkadian murders the exiled Poles one by one as they are located. Arkadian seems to be a threat to Lime himself until the sordid history is revealed to Arkadian’s beloved daughter, Raina. Faced with such exposure, Arkadian kills himself by jumping from his private plane.26

The radio episodes ‘Murder on the Riviera’ and ‘Blackmail Is a Nasty Word’ share additional plot elements with Welles’s Arkadin screenplay.27

* * *

The origins of Gregory Arkadi(a)n, aka Akim Athabadze, recall the villains of Eric Ambler’s early novels, who, according to Michael Denning,

are of uncertain nationality and, like the villains of earlier thrillers, oppose any nationalism. “One should not,” one of these entrepreneurs of information, Vagas, says [in Cause for Alarm, 1938], “allow one’s patriotism to interfere with business. Patriotism is for the cafè. One should leave it behind with one’s tip to the waiter.” Business has no frontiers, it crosses national boundaries with the best papers money can buy, and it crosses the frontier of legal and illegal without regard.28

When Welles announced Mr. Arkadin to L’Écran français in January 1952, he said it would “tell the misadventures of an arms dealer along the lines of Basil Zaharoff”,29 although later Welles described Zaharoff as “sly”, unlike Arkadin, who nevertheless “occupies a similar position” to such mysterious tycoons.30 Zaharoff, born in 1850 in Anatolia, was knighted by George V for providing arms to the Allied forces during World War I, although he was widely suspected of duplicity and even stoking war on both sides to create business. Welles played Zaharoff in a radio episode of The March of Time on the occasion of the tycoon’s death in 1936.31

Another source for Gregory Arkadin was Josef Stalin, who shared the character’s Georgian heritage. Welles elaborated that Arkadin was

cold, calculating, cruel, but with that terrible Slavic capacity to run to sentiment and self-destruction at the same time. The beard came from a wig-maker and the character came partly from Stalin and partly from a lot of Russians I’ve known.32

Welles more generally reflected that

Arkadin is the expression of a certain European world. He could have been Greek, Russian, Georgian. It’s as if he had come from some wild area to settle in an old European civilization, and were using the energy and the intelligence natural to the Barbarian out to conquer European civilization, or Ghengis Khan attacking the civilization of China. And this kind of character is admirable; it’s only Arkadin’s ideology which is detestable, but not his mind, because he’s courageous, passionate, and I think it’s really impossible to detest a passionate man.33

This thoughtfulness might suggest that in Gregory Arkadin Welles had created a tycoon of human complexity, a character with an emotional life as richly conceived as Charles Foster Kane’s. On the contrary, Arkadin is played by Welles with extreme artifice. His makeup, beard, hair, costumes, and accent are bizarre and affected. The performance is often singled out as the weakest aspect of the film.

Orson Welles as Gregory Arkadin

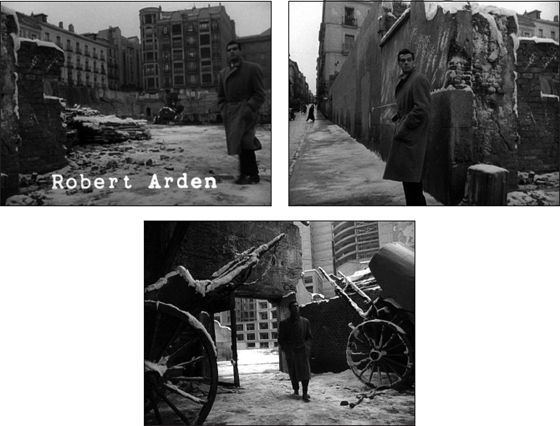

A key difference between ‘Man of Mystery’ and the film is the character of the investigator. Harry Lime is not simply renamed for legal reasons; he is transformed into Guy Van Stratten, a coarse and naive American “running American cigarettes into Italy”, far less cosmopolitan and wily than Harry Lime. Robert Arden’s performance as Van Stratten has also been widely criticised as inadequate. Jonathan Rosenbaum has defended Arden, locating the problem more in “the unsavoriness and obnoxiousness of the character rather than the performance itself”; Van Stratten is intended to be unattractive while “occupy[ing] the space normally reserved for charismatic heroes”.34 The character seems to have been reconsidered through successive drafts of Welles’s screenplay. The Masquerade draft, completed on 23 March 1953, has a European hero named ‘Guy Dumesnil’. The Van Stratten who narrates the English translation of Bessy’s Monsieur Arkadin – apparently based on a Welles script draft later than Masquerade but predating the shooting script – is worldly and sardonic.35

The mood of artificiality is enhanced by the casting of supporting actors outside the ethnicity and mother tongue of their characters. The Jakob Zouk character provides the framing conversation with Van Stratten in most surviving versions, an invention by Welles early during shooting. In the European Confidential Report of 1956, Van Stratten’s voice-over refers to Zouk as “a petty racketeer, a jailbird”. In the ‘Corinth’ version, Zouk characterises his release as the jail wanting “to save themselves the price of the coffin”. Although there are hints that Zouk is a Polish Jew – in the ‘Corinth’ he throws out such Yiddish reduplications as “gang schmang” and “killer schmiller” – it is inconceivable that a Jew would have emerged from a Munich prison circa 1954 after a fourteen-year stretch. Zouk is played by Akim Tamiroff, the brilliant Armenian comic actor who throughout his international film career specialised in ‘ethnic’ roles. For Welles alone he played an Italian gangster in Touch of Evil, a Mitteleuropean in The Trial, and Sancho Panza in Don Quixote.

The Polish diaspora characters were cast from all over Europe. Peter Van Eyck, who played Thaddeus, came closest to the character’s source; he was born in Pomerania, historically part of Germany but post-1945 located in Poland. The others are played by an Englishman (Michael Redgrave), a Hungarian (Frederick O’Brady), a Russian (Mischa Auer), a Greek (Katina Paxinou), and an ethnic Armenian of obscure birth (Grégoire Aslan). Susanne Flon, who plays the Baroness Nagel, was French. Welles had originally intended to cast the Swedish Ingrid Bergman as the Baroness and the German Marlene Dietrich as Sophie.36

Welles later claimed, “I wanted to make a work in the spirit of Dickens, with characters so dense that they appear as archetypes.”37 Critic William C. Simon remarks on the presentation of the film’s characters through “hyperbolic caricature”. Referring to Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of ‘social speech types’, Simon notes how in Arkadin these “speech types have a set of sociopolitical associations”:

Every character … speaks their dialogue with a pronounced accent. […] Their accents are drawn from conventionalised literary or social discourses of which there are a tremendous variety in the film. […] [A]ll evoke a set of associations related to a particular culture by its literary and popular mythology. Especially significant is the notion of Eastern European world-weariness, a tremendous sense of philosophical resignation and ennui that animates all the characters in the film.38

In Welles’s films, saudade for vanished times and places is typically expressed in tender anecdotal monologues or by symbolic objects such as Rosebud. In addition to his numerous other foreign affinities, Welles was particularly fond of an antiquated Mitteleurope – particularly of the self-inventing Hungarians. The Polish characters in Mr. Arkadin are variously exiled to Munich, Naples, Paris, Mexico City, Acapulco, Tangier, Copenhagen, and Amsterdam; Van Stratten’s interviews provide some of these lowlife refugees with the opportunity to voice their nostalgia for interwar Warsaw. Sophie, the former gang leader now married to a grotesquely mugging Mexican general, is particularly haunted by the memory of her Warsaw days with the dashing young Arkadin/Athabadze: “I was crazy in love with him, mister!” she says, and later clutches her photograph album to her chest. And if there is a Rosebud in Mr. Arkadin, it is Jakob Zouk’s traditional Christmas goose liver – “with applesauce, mashed potatoes, and gravy”. Close to death, he names that dish, traditionally most popular in Hungary, as the price of allowing Van Stratten to save his life.

* * *

To add to the artificial mood, the first few minutes of all versions of the film – and the European Confidential Report in particular – present a startling clash of modes. The opening quotation from Plutarch, about a poet who is willing to accept any gift from a powerful king except the burden of a secret, promises a fable; Welles’s narration over the aerial image of a pilotless plane purports to introduce a “fictionalised reconstruction” of scandalous true events; the credits, a montage of the colourful dramatis personae at their quirkiest, suggests a carnival of grotesques; and then Van Stratten’s working-class American voice-over evokes the atmosphere of pulpy hardboiled detective stories. Rosenbaum has cited the stylistic mishmash in Arkadin as an influence on the imminent French New Wave.39 The film was indeed praised in contemporary reviews by François Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, and in 1958 the critics of Cahiers du cinéma improbably selected the European release of Confidential Report as one of the twelve best movies of all time.40

Simon channels Bakhtin to explain Welles’s method:

Clearly, what Welles is doing in the opening moments of the film is to put into dialogic contact three diverse discourses: the fairy tale or legend of the paratext, the documentary reconstruction of the opening spoken lines, and a delirious hyperbolic aesthetic mode associated through the music score with a generalized Eastern European sensibility that will in fact prove to be the dominant mode of the film. This clash of discourses constitutes a positing of filmic heteroglossia and raises questions about the film’s conception. Will it be a fairy tale? Will it be a docudrama? Will it be a most elaborate Polish joke?41

Paul Misraki’s score is a collection of pastiches including Salvation Army brass band music (an original theme and ‘Silent Night’) and a buoyant orchestral dance theme with an Eastern European flavour. Misraki wrote the music without having read the screenplay or seen a cut of the film. Welles spliced together segments of Misraki’s recorded cues in abrupt juxtapositions.42

So these are Welles’s complicated generic, textual, and historical sources, the unconventional stylistic choices, and the production disasters surrounding Mr. Arkadin. In combination these factors left to posterity a confusing set of variant versions, none of them finished or approved by the director. And yet Welles’s political critique of postwar Europe is still palpable across the versions. By updating the ‘serious thriller’ to the era of international air travel and the Iron Curtain – unprecedented speed and freedom of movement for the privileged, authoritarian restriction for the majority – Welles illustrates the new ways that space is controlled and experienced in a dizzying vision of erased distances that anticipates the internationalism of the James Bond films of the 1960s.

We also glimpse deliberately imagined urban terrains where traces of the past break through the material structures of the city. These palimpsestic spaces make for a suitable metaphor for postwar Europe. They reinforce Welles’s privileging of antiquated cultural affiliations, idealised and evoked in nostalgic reverie or symbolic objects, over the arbitrary political divisions of nationhood and the ideological divide of the Cold War. This is most pronounced in the rubblescape of Munich.

* * *

In the best of today’s films, there’s always an airport scene, and the best yet is in Confidential Report when Arkadin finds the plane full and shouts out that he will offer $10,000 to any passenger who will give him his seat. It is a marvelous variation on Richard III’s cry, “My kingdom for a horse,” in terms of the atomic age.

– François Truffaut, 195643

In the ‘St-Germain-des-Prés’ episode of Around the World with Orson Welles, filmed in 1955 after his departure from the Arkadin editing suite, Welles diplomatically lauds the airlines of Europe, but also voices nostalgia for “old-fashioned travel of all kinds. Not only old-fashioned trains … but old boats and barges and gondolas and canoes, ox-carts … anything that takes long enough to give you a chance to see where you’re going before you get there.”44

The port city of Naples was devastated during the war, but its rubble is not depicted in Mr. Arkadin. Welles shot at least part of the Naples sequence, the murder of Braco, in Madrid.45 The sequence is built from expressionistic low-angle and canted shots which sometimes pan non-horizontally in a clever visual echo of the lopsided run of Braco’s peg-legged assassin. Welles projects the assassin’s distorted shadow against shipping crates. The montage does not maintain any sort of coherent spatial continuity in any version of the film. According to Lucidi, the first four sequences in the ‘Corinth’ version – which would therefore include the Naples sequence – appear as Welles intended.46 The fictional space of Naples marries the iconography of ships and trains – two typical transitory settings of the 1930s ‘serious thriller’.

But time has moved on and air travel now provides the dominant passage of movement for the powerful. The expansive international settings of Mr. Arkadin are only possible in the age of flight. The plane’s centrality to the world of Arkadin is indicated by the opening image in all versions – an empty plane in the sky. Later, the incredible reach of Van Stratten’s international investigation is conveyed by montage sequences incorporating images of planes and airports. Key moments of drama occur at airports in Barcelona and Munich. In one deleted scene Van Stratten and Raina talk on a tarmac, presumably in Barcelona, and leave Raina’s glum English suitor sitting alone on a ramp stairway leading nowhere.47

The age of air travel in Mr. Arkadin

At the edges of the tarmac in Barcelona are half-completed concrete buildings that resemble the unfinished structures surrounding Sebastianplatz in Munich. Yet whereas rubble-strewn Munich exposes layers of its history, El Prat airport in Barcelona is a bland open tarmac in arid country.

The drama’s climactic moment occurs in Barcelona’s central air-traffic control tower. Here Raina communicates with her disembodied father, who is mostly represented by shots of a ceiling-mounted loudspeaker. With Arkadin’s suicide the loudspeaker falls silent.

The variant versions of Mr. Arkadin indicate that the film’s international settings were not fixed from conception but evolved over the long period of production. Apart from ‘Man of Mystery’, Welles left as evidence other early drafts (of sorts): the March 1953 Masquerade script, the ghostwritten novelisation, and the Spanish versions. This Masquerade script sets Arkadin’s masked ball in Venice rather than its eventual location, Spain. In that version of the script Welles explicitly cites as precedent the ball thrown by the Mexican millionaire Carlos de Beistegui in Venice on 3 September 1951.48 Welles was in attendance and reported on the event for the Italian weekly Epocha:

Rehearsing at St. James’s Theatre in London I thought about the costume I would wear to the ball. Impossible to move Othello into the eighteenth century. Too far. Cagliostro was just right. I got there without the costume, of course, which hadn’t arrived from Rome. I get distracted, as everyone knows. Some think I do it deliberately. But that evening, at eight o’clock, I suddenly realized I had no costume. I had to improvise. At the [Hotel] Danieli they found me a turban, something between a lady’s art nouveau hat and the headdress of a Sioux Indian chief…49

Other guests included Gene Tierney, Salvador Dalí, and Christian Dior. Winston Churchill, also in the city, had to skip the party lest he appear to his constituents as indulging in “conspicuous luxury”.50 When the film became a Spanish co-production, this long party segment was transferred to a castle whose exteriors were provided by the Castillo Alcázar in Segovia. Welles drew on Francisco de Goya to create the visual motifs of the ball.

The early incarnations use New York City as the setting for Arkadin’s dinner with the Baroness Nagel. The Spanish versions include establishing shots of the New York City skyline and dialogue that describes the Baroness (played here by Amparo Rivelles) as a saleswoman on Fifth Avenue. The second confrontation scene between Arkadin, Van Stratten, and Raina also occurs in New York. The ‘Corinth’ version and Confidential Report shift these events to Paris, adding location shots of Van Stratten in Pigalle, outside Maxim’s restaurant, and in conversation with a man played by Louis Dolivet in sight of the Eiffel Tower. Paris was the last of Arkadin’s locations to be filmed, although there seems not to be any particular dramatic reason for these scenes to have occurred in Paris rather than New York.

Hired by Arkadin to investigate the tycoon’s amnesia-clouded origins, Van Stratten sets out with all expenses paid. Two variant versions of the same montage sequence contain totally different investigative itineraries. Van Stratten’s variant voice-overs narrate a montage of cross-faded shots, some of which appear to be stock footage and others to be shot especially for Arkadin: the point of view inside a wheel well as a plane lifts off the ground, display boards listing international destinations, Van Stratten crossing the tarmac in front of a stationary Aerolíneas Argentinas jet, a taxiing TWA plane, and then Van Stratten’s interviews with people in various outdoor urban locations. The interview shots are often concluded by a whip-pan (always to the right) that cuts mid-blur into the next shot. This transitional device goes back as far as the breakfast sequence of Citizen Kane, but Welles would use it extensively in Around the World the following year.

The images are identical in each version, but the voice-over varies. In the ‘Corinth’ version, Van Stratten narrates:

I did a lot of travelling and asked an awful lot of questions before I learned the truth. From Helsinki to Léopoldville, Brussels, Belgrade, Beirut, Torino and Trieste, Marseille and Mogador. I talked to every crook who’d even been around in 1927. And a whole lot of other characters, besides.

And in Confidential Report:

My travels took me from Helsinki to Tunis, Brussels, Amsterdam, Geneva, Zurich, Trieste, Marseille, Copenhagen. I talked to every crook who’d even been around in 1927. And a whole lot of other characters, too.

The variations are probably two alternative improvised takes from the same dubbing session. The cities Van Stratten visits have no particular political or historical significance; the names seem to have been plucked out of the air, in the first version for their alliterative value. But the striking impression gained from both versions is Van Stratten’s ease and speed of movement while on Arkadin’s payroll. Welles lived a similarly fast, peripatetic, aeroplane-enabled working life in the 1950s as he struggled to make films across Europe. And yet, even in Welles’s privileged position as an international film star, he was frustrated by the limitations on his freedom of movement.

Shortly after making Arkadin, Welles filmed a television monologue denouncing “red tapism and bureaucracy” in relation to “freedom of movement”.51 The age of the Iron Curtain clearly restricted movement between East and West, but there were also numerous other bureaucratic restrictions of movement within Western Europe before the invention of the European Union.

Welles’s essay ‘For a Universal Cinema’ lamented the logistical difficulties of Pan-European filmmaking in this era:

I was developing the rushes of Arkadin in a French lab. Can you imagine that I had to have a special authorization for every piece of film, even if only 20 yards long, that arrived from Spain? The film had to go through the hands of the customs officials, who wasted their time (and ours) by stamping the beginning and end of each and every roll of film or of magnetic sound tape. The operation required two whole days, and the film was in danger of being spoiled by the hot weather we were then having. The same difficulties cropped up when it came to obtaining work permits.

My film unit was international: I had a French cameraman, an Italian editor, an English sound engineer, an Irish script girl, a Spanish assistant. Whenever we had to travel anywhere, each of them had to waste an unconscionable amount of time getting special permissions to stay to work… Similar complications arose when, for example, we had to get a French camera into Spain…

Welles cited the problem of producers who “prefer the security of a limited but certain profit from a national or regional market to the infinitely wider possibilities of a world market, which would of course entail, at the outset, certain supplementary expenses”.52 He also wrote: “The challenge of time is one that I can accept… I am perfectly willing to fight that duel. But there is another, the futile and insidious struggle against the thousand and one formalities by which cinema finds itself chained down.”53

The logistical torment of Welles’s European co-production was foreshadowed in the film’s very subject matter. The bureaucratic “importance of papers” that we see in the Ambler novels of the 1930s is updated to the Cold War. It is significant that at the outset Van Stratten is a petty smuggler jailed in Naples for bringing contraband American cigarettes into Italy (Bessy’s novelisation gives more detail on Van Stratten’s work for Thaddeus’s smuggling operation out of Tangiers). Van Stratten acquires true freedom of movement only when he goes on Arkadin’s payroll as an investigator. The moment is marked by a series of jump-cuts depicting different currencies thrown down onto a table. Arkadin’s wealth and access to the network of air travel diminish the relevance of national borders.

Eric Rohmer recognised this at the time of the initial European release of Confidential Report:

[Arkadin’s] wealth resides less in possessions than in that most modern of powers, mobility, the ability to be present at practically the same time in every part of the globe. A life of travel, of palaces, seems gilded with a magic that sedentary luxury has lost … the power of money is depicted with a precision that only Balzac would not have envied.54

This ‘power in mobility’ is only possible in the age of air travel. As if to underscore that point, when Arkadin is unable to secure a seat on the Christmas Eve plane from Munich to Barcelona in order to prevent Van Stratten’s revelations to Raina – his “My kingdom for a horse” moment, as Truffaut put it – he takes advantage of the luxury of a private plane that he pilots himself. When he believes his past has been exposed to Raina, Arkadin abdicates his metaphorical throne by jumping to suicide.

* * *

The city of Munich is at the centre of Mr. Arkadin, most particularly in the ‘Corinth’ version, which preserves the most extensive structural frame for flashbacks. Nevertheless, the 1956 Confidential Report offers a unique element in Van Stratten’s opening voice-over, which specifically locates Jakob Zouk’s attic at ‘Sebastianplatz 16’, a non-existent address in Munich; the location is actually the tenement behind Sebastianplatz 3. The film does not attempt architectural verisimilitude. A fictional cinematic space was constructed freely, and sometimes clumsily, from the material shot on location, quite possibly by Welles himself in the editing room. One example among many: in both the ‘Corinth’ version and Confidential Report, Van Stratten appears to enter the snow-blanketed courtyard of the tenement, cross the courtyard while gazing up to the attic, and then prepare to mount the stairs. In actuality he has entered the courtyard twice in successive shots from two entirely different entrances. Arkadin’s later entrance into the same courtyard replicates this nonsensical movement and succession of shots.

In the various exterior shots of Munich, particularly around what purports to be Sebastianplatz, Van Stratten wanders through a ‘berubbled mise-en-scène’, a term I borrow from Robert R. Shandley’s analysis of Germany’s Trümmerfilme (‘rubble film’) cycle of 1946–49. Some of the better-known titles in that cycle include Die Mörder sind unter uns (The Murderers Are Among Us, Wolfgang Staudte, 1946) and Zwischen Gestern und Morgan (Between Yesterday and Tomorrow, Harald Braun, 1947).55

The rubble films have not been historically valued for their aesthetic qualities; after all, German films of this era were subject to the control of the occupying Allied military forces, intended to be a propaganda tool to ideologically rehabilitate the German public in the post-Nazi era. But recent critical re-evaluations have argued for the rubble films’ ability to evoke the political complexities of their historical moment through their presentation of berubbled space. Between Yesterday and Tomorrow was shot at Munich’s Regina Palast Hotel, which had been partially destroyed in the war. The film tells parallel narratives of pre- and postwar events, drifting between the damaged and surviving sections of the hotel. As Jennifer Fay observes, “the filmed images of the hotel signify both palimpsestically and spatially”. Moreover, the film “encrypts the provisionality and temporality of life in catastrophe’s wake. […] [It] participates in a materialist historical reckoning that is concerned with the erasure of history and the end of a corrupt social order whose remnants are everywhere.”56 Ironically, many other films in this cycle were shot in studios rather than in actual berubbled locations.57

While Shandley restricts his canon to German films made in the period 1946–49, the Munich sequences of Mr. Arkadin seem to constitute a kind of ‘rubble film’, even though Mr. Arkadin emerged from a completely different production model, censorship regime, and later period.

In a rubblescape the damaged structures reveal traces of the past. In Welles’s Munich the bombed, broken walls reveal layers of historical strata – concrete, bricks, and stone. The city is a palimpsest. Partially destroyed buildings expose anachronistic relics from the past, such as the horse carriages of ‘Sebastianplatz’. The unfinished prefabricated concrete buildings herald the future. But despite first appearances, Arkadin does not innocently or inadvertently document a passing historical moment in the postwar reconstruction of Munich. The ‘berubbled mise-en-scène’ was not merely found while shooting on location in Munich but instead contrived with exhilarating artfulness.

The Christmas setting is dramatically essential to provide a trigger for Zouk’s nostalgia for goose liver. For many decades the shooting chronology, like so much other information concerning the Arkadin project, was obscure. Now it is known that the Christmas scenes were filmed in Munich during April and May of 1954 – mild springtime.58 The wintry city is so convincingly faked with banked snow and billowing flakes – all the bitterness of a Bavarian winter – that few seem to have ever realised those scenes were not really shot in December.

Van Stratten in the Munich rubblescape

Welles hardly pursued the methods of the Italian neorealists when shooting on location. He did not seek to film some equivalent of documentary ‘truth’. In the 1950s he pursued ways of transforming found urban structures – immovable streets and buildings – by embellishing them with powerfully symbolic detritus. Radically adapting what he found in real locations served Welles’s dramatic, thematic, and ideological purposes. We see this again a few years later in Touch of Evil.

Welles had already publicly expressed the very criticisms of contemporary Germany at the centre of his imagined Munich in Mr. Arkadin. He had staged his theatrical revue An Evening with Orson Welles throughout Germany in the summer of 1950, and caused an uproar when he accused the country of lingering Nazism in a newspaper column.59 That phenomenon is directly implied in Arkadin by the upside-down Hitler portrait and a swastika abandoned by a previous tenant in Jakob Zouk’s attic. As Welles later told Peter Bogdanovich, “There’s been instant de-Nazification, so of course the attics all over Germany filled up with such sacred relics.”60 The attic interior was a studio set in Madrid and the sequence was among the earliest filmed, shot long before the production moved on location to Munich.61

Van Stratten’s search for the goose liver takes us into the streets of Munich by night. His comic quest allows Welles to emphasise again the bombed-out cityscape, its engulfing shadows and silhouetted ruins.

The Allies had bombed Munich numerous times during the war. Jeffrey Diefendorf’s In the Wake of War recounts that Munich was left with five million cubic metres of rubble, supposedly double the matter contained within the Great Pyramid. It covered thirty-three per cent of the city. But of the big German cities, Munich was among the quickest to be cleared. Even by mid-1949, eighty per cent of its wartime rubble was gone.62 Certainly by the time of Mr. Arkadin, Munich had overwhelmingly been rebuilt.

The Hollywood thriller The Devil Makes Three (Andrew Marton, 1952) was filmed partly on location in Munich a few years before Arkadin. It begins with a prologue, an authoritative direct-to-camera address by a United States military officer. He establishes a chronology of Munich’s postwar reconstruction as of 1952, showing both the restoration of the city’s traditional architecture and the construction of new Modernist buildings.

This prologue is followed by a flashback to the drama, set in the year 1947, when rubble still overwhelmingly dominated the city. The Devil Makes Three’s prologue corroborates Diefendorf’s history of the pace of Munich’s reconstruction. Considering that the Munich sequences of Arkadin were not shot until the spring of 1954, it seems Welles overemphasised material traces of the war, that he made a deliberate decision to ‘berubble’ his mise-en-scène just as deliberately and impressively as he had dressed the springtime streets in fake snow. Although Mr. Arkadin is ostensibly set in the present, the rubble evokes the grimmer condition of the Munich of the mid-to-late 1940s.

Van Stratten in the Munich rubblescape

The Devil Makes Three (1952): Stills from the prologue including documentary footage of the rubble adjacent to the destroyed headquarters of the Nazi Party, the ‘Brown House’, in Munich

In short, Mr. Arkadin is an unreliable representation of the historical Munich of 1954. Welles’s cinematic city is richer than what might have been captured through any realist approach, as it arose from the encounter of found Munich locations with Welles’s political perspective on divided Germany. The palimpsestic rubblescape on screen not only is the bleak and unfriendly final stop for the dying Zouk, but also serves as a microcosm of Cold War Europe. Like Gregory Arkadin, Europe itself seems to be faking a condition of amnesia. Strictly policed national borders have divided politically obsolete cultural unities that nevertheless keep breaking to the surface via artefacts and nostalgic memories. Vehemently anti-nationalist, Welles makes a mockery of the fictions of nationhood.

The film was unfortunately botched by the circumstances of its making. Nevertheless, even in its unsatisfying variant versions, Arkadin is the closest Welles came to dramatising his vision of national identity and the operation of power in the cities and skies of 1950s Europe. The bureaucracy of borders and passports remains the means of controlling and dividing the common people; the wealthy obtain their power through an aerial mobility that circumvents such control.

NOTES