I move from one kind of architecture to another in my dreams without any difficulty whatsoever.

– Orson Welles, 1981

Continuing to make his living as an actor across Europe, Welles performed a small role in Abel Gance’s Napoleonic epic Austerlitz (1960), produced partly in Yugoslavia by Michael and Alexander Salkind. The Salkinds, father and son, were a Russian dynasty of film producers with a reputation for fly-by-nightism. Sometime during the winter of 1960/61 they approached Welles to write and direct an adaptation of Nikolai Gogol’s Taras Bulba (1835). Welles later explained that the producers arrived by long-distance taxi to offer him the job while he was vacationing in the Austrian Alps. After securing Welles’s services, they asked to borrow their taxi fare back to Innsbruck. It was a harbinger of the lean season ahead, although Welles later said the Salkinds’ plan to make a movie without any money was “wonderful”.

Welles wrote a Taras Bulba script. When a rival motion picture adaptation went into production in Salta in the north of Argentina, the Salkinds presented Welles with an alternative list of story properties. He decided on Franz Kafka’s Der Prozess (The Trial), which had been published posthumously in 1925.

The Salkinds set up a multi-national co-production – French, Italian, and German – that forced Welles to select actors and technicians from the different participating national film industries. He later said it was no great restriction. As on Arkadin, Welles worked with a limited budget and weathered unstable financial circumstances during shooting. He had to provide emergency funds to the budget himself. He also experienced again the frustrations of trying to work in collaboration with a fledgling state film industry, this time in Yugoslavia.1 Through the 1950s Yugoslavia had gradually opened up its production facilities to international co-productions. For film producers, the Yugoslavian landscape promised “every kind of terrain and weather, from snow-covered Slovenian mountains to lush, blue Adriatic Ocean within hours of each other”.2

Welles’s patchwork methods and ability to improvise saved the project from cancellation. This time he was able to reconcile his editing process to the demands of his independent producers. Although he missed a deadline to finish the film in time for the 1962 Venice Film Festival, the Salkinds did not fire him.3 He finished his final cut immediately before the film’s premiere in Paris that December. As such, The Trial is a fully realised Wellesian creation, the first film he was able to complete to his satisfaction in a decade.

Kafka’s novel provided Welles with another opportunity to explore freedom, the law, and bureaucracy in the context of an invented postwar European city. Like Arkadin’s Munich rubblescape, the city of The Trial contrasts a grim present with the traces of a now divided, politically obsolete culture of Mitteleurope. But rather than reveal traces of the past palimpsestically in a rubblescape, the labyrinthine city of The Trial mashes wildly different built structures: monuments of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with Modern collectivist urban planning – architectural languages that expressed radically different ideologies.

Unlike Arkadin, The Trial lacks any typical Wellesian expression of saudade for this Mitteleuropean past. Welles’s evocation of that past is limited to the material cityscape itself. This is part of the reason why, despite moments of comedy, The Trial is his bleakest movie, alongside Macbeth.

* * *

Kafka’s novel recounts the trial of Joseph K., a bank clerk, who is arrested for unexplained reasons one morning. He is left at liberty for a time, and is determined to denounce the illegitimacy of the whole legal process to which he is subject. The nature of the charges against him are never revealed. Following a long series of unsuccessful attempts to resolve his case, K. is led to a quarry outside the city and executed in such a way “as if he meant the shame of it to outlive him”.4

Although in most cases faithful to the source text, at least as the unfinished novel had been published and translated, Welles departed from Kafka and personalised the material. He rearranged the chapters and changed the ending of K. submitting meekly to execution, because it “stank of the old Prague ghetto” and was untenable to Welles after the Holocaust. He also instructed Anthony Perkins to play K. as a socially ambitious schemer.5

The parable ‘Before the Law’, which originally appeared during Kafka’s lifetime in his collection Ein Landarzt (A Country Doctor, 1919), is also told to K. by a priest towards the end of The Trial, as part of “the writings which preface the Law”. A man from the country comes begging “for admittance” to the law, which is patrolled by a guard. After making the man wait until he is near death, the guard finally admits: “No one but you could gain admittance through this door, since this door was intended only for you. I am now going to shut it.”6 Welles narrates this haunting, fatalistic parable as the prologue to his film, illustrating it with a series of ‘pinscreen’ illustrations by Alexander Alexeieff and Claire Parker that follow Kafka’s hints by visualising the abstract law as a closed city or fortress.

“Before the Law”

Following the prologue, K. attempts to navigate a labyrinthine city which is almost reduced to the spaces of his nonsensical trial – its courts, law offices, and, finally, execution site. Kafka’s setting is a non-specific Mitteleuropean city in which time and space are vague. The unfinished nature of the manuscript only enhances its vagueness. K.’s search for a resolution to his case has been described as “an exploratory journey through the ‘phantasmagoria’ of the modern city, a space defined by surfaces, theatrical scenarios, and unreadable representations”. He is an alienated individual in the modernist tradition, unable to contain a total vision of the city.7

Welles reinvents Kafka’s city setting for the screen. The Trial’s frequent spatial absurdity is licensed by Welles’s explanation at the outset that the film follows the “logic of a dream… a nightmare”. His screenplay contained a longer, more explicit narration that did not make the final cut: “Do you feel lost in a labyrinth? Do not look for a way out, you will not be able to find it. There is no way out.”8

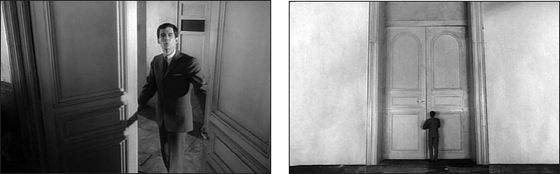

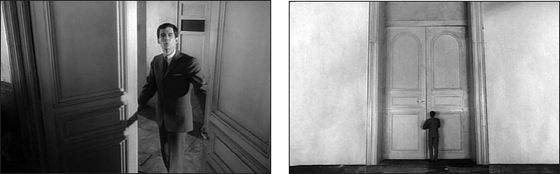

The unnavigable labyrinth, implicit in the source material, happily chimed with Welles’s Pan-European patchwork method. He filmed through the first half of 1962 in at least three different European countries and, as with Othello, sometimes cut together shots acquired from disparate locations. The illogical spaces of the city are flaunted in the dialogue. When K. exits through a tiny door in the studio of the court painter Titorelli, he finds himself back in an uncomfortable place he’d only recently escaped: “This is the law court office,” he says in bewilderment. It forces him to admit his surprise at the extent of his ignorance of “everything concerning this court of yours”. Moreover, spatial relationships between the characters and objects are sometimes malleable from shot to shot. In another scene K. exits the Interrogation Commission Hall; in the counter-shot from outside the door looms absurdly large over K.’s tiny figure:

This is not to imply that Welles was indifferent to visual continuity; in fact, Welles’s meticulous work with cinematographer Edmond Richard ensured an aesthetically consistent image of extremely deep contrast so as to allow Welles flexibility in editing.9 The film’s expressionist aesthetic – its deep focus and abysmal darkness – is a major triumph in a body of work that always demanded the best of cinematographers.

* * *

Welles did not make a period film set in Kafka’s late 1910s. He freely blended nineteenth- and early twentieth-century buildings with the unmistakably contemporary architecture of Europe. The wild internationalism of Mr. Arkadin was succeeded by a single imagined urban setting that was intended to evoke the flavour of Kafka’s Prague but that follows the author’s example in blurring its exact location. The cast again provided a smattering of accents – American, French, English, German, Italian, and Akim Tamiroff’s Akim Tamiroff. Welles shot the film by combining footage from Zagreb, Paris, and Rome. In Zagreb he sought the “flavor of a modern European city, yet with its roots in the Austro-Hungarian empire”. At the time he said, “I never stopped thinking that we were in Czechoslovakia”:

It seems to me that the story we’re dealing with is said to take place ‘anywhere.’ But of course there is no ‘anywhere.’ When people say that this story can happen anywhere, you must know what part of the globe it really began in. Now Kafka is central European and so to find a middle Europe, some place that had inherited something of the Austro-Hungarian empire to which Kafka reacted, I went to Zagreb. I couldn’t go to Czechoslovakia because his books aren’t even printed there. His writing is still banished there.10

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, politically united in 1867, had collapsed with the end of World War I, around the time Kafka wrote The Trial. Vienna and Budapest had been the joint political and cultural capitals of the dual monarchy. Welles knew both cities intimately as a boy in the 1920s and had soaked up the surviving ambience of a recently vanished age. He later recalled old Vienna with idealistic affection in two short television documentaries, and had a particular fondness for Hungarians of the period such as art forger Elmyr de Hory and producer Alexander Korda; eccentric, self-inventing exiles born in the dying days of the dual monarchy.

But Kafka’s Prague had been overshadowed by the cultural centrality of the dual capitals – and Zagreb even more so. By the 1940s the territory of the former dual monarchy had been bisected by the Iron Curtain. Croatia was now contained within the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. It has been said that for much of its history Zagreb had the character of a capital city that lacked an enveloping nation; its complicated history was representative of a long-term disjunction between the spaces of political power and the spaces to which people attached their identity.11 As one historian writes:

Culturally, Zagreb has been defined by its strategic position as a crossroads between cultures and identities. Situated at the ‘centre of the edge’ of the great European empires and multinational states: Rome and Byzantium, Habsburg and Ottoman, the USSR, Yugoslavia, and, now, the European Union, Zagreb has occupied a strategic position at the intersection of north and south, orthodox and Roman Catholicism, Slavic and Mediterranean cultures.12

Josip Broz Tito broke relations with Stalin and the Soviet Union in 1948, but even before that Zagreb’s development reflected the Yugoslav state’s distinct urban planning trajectory. While communist Europe was generally forced into embracing Socialist Realist architecture, Zagreb remained committed to the international Modernist avant-garde, a style “untainted by associations with past imperial subjugation or politically-charged vernacular traditions”.13

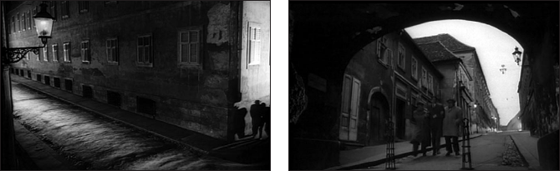

Even after the Salkinds’ original plan to construct sets in a Zagreb studio was abandoned, Welles persisted with the city for its locations. In his words, postwar Zagreb’s urban topography provided “both that rather sleazy modern, which is a part of the style of the film, and these curious decayed roots that ran right down into the dark heart of the nineteenth century”.14 In fact, only a few scenes in the final cut depict architectural remnants of the Austro-Hungarian epoch: a brief scene inside the Croatian National Theatre (which opened in 1895), outside the Zagreb Cathedral (restored in a neo-Gothic style in 1906), and K.’s forced march through the old streets towards his execution on the periphery of the city.

Otherwise Zagreb’s Modernist topographies are emphasised. Welles’s attitude towards Modernist architecture was unwaveringly negative. It had crept into the periphery of Welles’s mise-en-scène as early as the pre-fabricated concrete shells rising above the rubble of Munich and in the arid fields surrounding the Barcelona airport in Mr. Arkadin. Welles disliked Michelangelo Antonioni – he called him a “solemn architect of empty boxes”,15 presumably in reference to the austere postwar Italian cityscapes of La Notte (1961), L’Eclisse (1962), and Il deserto rosso (The Red Desert, 1964). Later, the film-within-a-film in The Other Side of the Wind was apparently intended as a parody of Antonioni’s ponderous style. Welles screened one sequence in a rough cut at the 1975 AFI Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony: a young man (Bob Random) in pursuit of a woman (Oja Kodar) through Los Angeles’s Century City, a then still-embryonic Modernist redevelopment of the former Twentieth Century Fox backlot. Welles invented his own Modernist cityscape through reflections in glass and mirrors.16 And at the climax of Welles’s late script The Big Brass Ring, a presidential candidate murders a blind beggar in Madrid in the vicinity of “some ghastly housing scheme, new in the last days of the Generalissimo, and already fallen into the sordid decay of cheap construction… Buildings like big ugly boxes are crammed together on the barren earth where not a tree or blade of glass is growing.”17

K. at the Croatian National Theatre and the Zagreb Cathedral

The march to execution

In the 1930s Zagreb’s planning authorities embraced the utopian tenets of the Congrés internationale de l’architecture moderne (CIAM), guided by a belief in the ability of Modernist architecture and town planning to transform society.18 With the postwar federation of communist Yugoslavia came Vladimir Antolić’s General Plan of Zagreb (1947). Antolić inherited the city’s pre-war regulation plans and synthesised them with other architectural influences, including Le Corbusier. He created an ambitious scheme for a socialist city centre to be built around what was temporarily called Moscow Avenue, and eventually became the Avenue of the Proletarian Brigades.19 The ideological thrust of the Antolić General Plan was to organise space for the collective, “according to a different set of spatial hierarchies from the traditional bourgeois city”.20 Due to the expense of its implementation, the Antolić General Plan was never officially accepted, only went ahead in piecemeal stages around the Avenue of the Proletarian Brigades through the postwar era, and was never finished.21

Welles arrived to film The Trial in 1962 in the midst of this slow, ideologically guided transformation of Zagreb’s urban landscape. Despite his nuanced appreciation of Yugoslavia’s non-Soviet form of communism, Welles saw little distinction between Yugoslav and Soviet urban planning. In 1962 he described filming the “hideous blockhouse, soul-destroying buildings [of Zagreb], which are somehow typical of modernist Iron Curtain architecture”.22 It’s hardly surprising that the self-defined “man of the Middle Ages” recognised the oppressive quality of the postwar cityscape of Zagreb, despite its ostensible ideological basis in anti-bourgeois collectivist social relations. Welles lamented the loss of much older forms of social organisation.

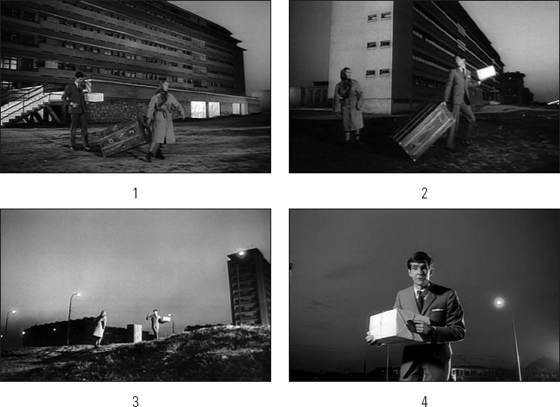

Figs 1-3: Frames from the tracking shot from Madame Grubach’s boarding house to the Avenue of the Proletarian Brigades; Fig. 4: K. stands at the edge of the Avenue

In The Trial Welles consistently uses Modernist spaces as the context of alienation. One comic scene of miscommunication was filmed in a tracking shot that follows K. and Miss Pittl across an urban wasteland at dusk. The characters move from the concrete slab where Madame Grubach runs her boarding house to the Avenue of the Proletarian Brigades, the principal thoroughfare and tram route of the socialist city plan.23

Welles was particularly happy to be able to film inside a cavernous exhibition hall at the Zagreb Trade Fair because it provided a filming space on a scale unavailable in France or England.24 These halls, on the other side of the Sava River, were built in the late 1950s and became a rare trade crossroads for the antagonists of the Cold War, the only trade fair to host the innovations of the United States, the Soviet Union, and the developing world.25

Zagreb Trade Fair interior sequence in The Trial

Inside the hall Welles filmed hundreds of typists working at rowed desks. K. apparently lords over this surreal factory of typing minions, dehumanised and regulated by a clock. And yet even with the material shot within this open-plan interior, Welles’s editing blatantly ignores the true layout of the space. In one sequence K. finds the storeroom where his investigators are being flogged as a result of his complaints. The storeroom is located under a staircase. K. escapes the room, crosses the floor of typists, and sits with his uncle in his unpartitioned office. But when the typists depart en masse, K. marches further away from the staircase; yet somehow he quickly finds himself right back there.

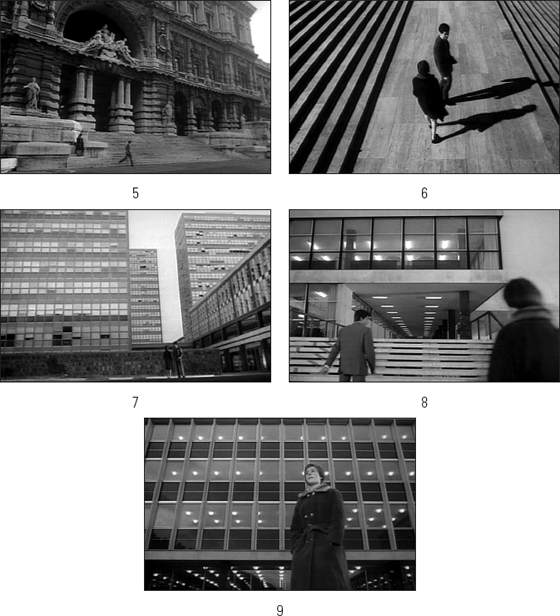

Welles combined Zagreb locations with material shot in other cities. A bold use of the patchwork technique comes in a sequence following K.’s panic attack in the law court offices. Welles lines up successive shots from different locations. Despite no evident spatial connection between these locations, the scene is given continuity by the movements and continuing dialogue between K. and his niece Irmie.

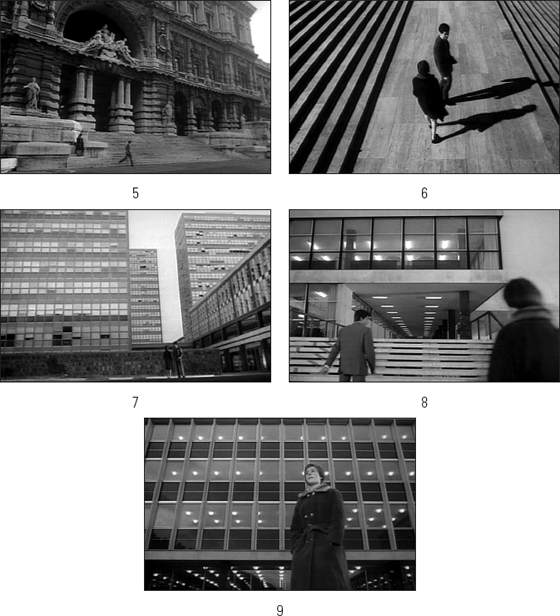

K. encounters Irmie outside Rome’s Palace of Justice (fig. 5); Irmie follows K. across the wide landing of a stone staircase clearly not in the same vicinity (fig. 6). As K. turns back to speak face to face with Irmie, Welles cuts to a long shot that positions the pair no longer on the staircase, but instead in front of a complex of office buildings (fig. 7), possibly filmed in Rome’s Esposizione Universale Romana district, originally a Mussolini-era project (Welles had location scouted there as far back as 1952 for a mooted Julius Caesar; Antonioni had only recently used the area in parts of L’Eclisse26). K. continues to walk alone towards what is supposed to be his office building (fig. 8). Welles did not use the trade fair for the exteriors but instead used the Zagreb Workers’ University on the north side of the river, two kilometres west of K.’s lodgings further along the Avenue of the Proletarian Brigades. The counter-shot of Irmie places her in front of yet another steel and glass edifice of an unknown location (fig. 9). A contemporary photograph of the Zagreb Workers’ University shows this building is not in the vicinity of the university’s front staircase.

The low-ceilinged interiors of Mme Grubach’s boarding house, where investigators transgress into K.’s private room and arrest him as he wakes, were built inside the Studios Boulogne in Paris. The first scenes for the film were shot here from 26 March 1962.27 Welles remembered having to pay the English actress Madeleine Robinson himself to prevent her walking off the set, indicating the shaky state of the Salkinds’ finances from the beginning of production.28

The film was only finished due to its director’s magnificent ability to “preside over accidents”. Welles had designed additional sets with the assistance of art director Jean Mandaroux intended to be constructed in Zagreb, presumably at Jadran Film Studios. Welles explained at the time of the film’s release:

I had planned a completely different film that was based on the absence of sets. The production, as I had sketched it, comprised sets that gradually disappeared. The number of realistic elements were to become fewer and fewer and the public would become aware of it, to the point where the scene would be reduced to free space as if everything had dissolved.29

That concept had to be abandoned. In later years Welles often told an anecdote about how he solved a budget crisis that forced him to abandon the sets and threatened the picture’s very continuation. A creative epiphany emerged from an almost hallucinatory urban misperception in Paris. The epiphany led him to shoot large portions of The Trial inside the Gare d’Orsay.

Welles gave contradictory explanations for the budget crisis. In some versions he blamed the financial problems of the Salkinds: they either had no money for set construction, or else had been blacklisted by the Yugoslavian industry because they still hadn’t paid off their debts for Austerlitz.30 But years later, Welles blamed corruption within the state film industry. He explained that Yugoslavian producers, “like all people who have lived under occupation for a long time – the Yugoslavs had lived for four hundred years under the Turks – […] [they] learn, as an act of honour, to steal from strangers.”

In this version the Yugoslavians played a “trick” they’d “played on hundreds of Italian co-producers”. They waited until shooting was imminent to announce they had “miscalculated” the cost of building the sets, and hence demanded more money – or else partial ownership of the film. The Salkinds “didn’t even have the money to pay our hotel bill in Zagreb”, let alone pay the additional demands; so Welles put the entire cast and crew on a night train out of the country.31 Welles later acknowledged that the Salkinds ran out on the company’s bill at the Hotel Esplanade in Zagreb. He also recalled a narrow escape a few years later from the Zagreb hotel manager, who tried to apprehend Welles while he was shooting Denys de La Patellière and Raoul Lévy’s Marco the Magnificent in Belgrade, four hundred kilometres away. A Yugoslavian snowstorm prevented the manager’s arrival.32

Whatever the cause of the cancellation of set construction for The Trial, Welles’s solution was inspired. Drinking with actress Jeanne Moreau in the early hours of the morning at the Hôtel Meurice on the Rue de Rivoli, Welles gazed out of his window and saw a puzzling image in the sky of Paris: two moons. Moreau pointed out he was really looking at the twin clock faces of the Gare d’Orsay across the Tuileries and the Seine. They crossed the river to the empty train station, where Welles said he

discovered the world of Kafka. The offices of the advocate, the law court offices, the corridors – a kind of Jules Verne modernism that seems to me quite in the taste of Kafka. There it all was, and by eight in the morning I was able to announce that we could shoot for seven weeks there.33

The Gare d’Orsay had been built in 1900 in the French Beaux Arts style. By 1962 it was largely out of use. Welles was conscious of its historical resonance:

If you look at many of the scenes in the movie that were shot there, you will notice that not only is it a very beautiful location, but it is full of sorrow, the kind of sorrow that only accumulates in a railway station where people wait. I know this sounds terribly mystical, but really a railway station is a haunted place. And the story is all about people waiting, waiting, waiting for their papers to be filled. It is full of the hopelessness of the struggle against bureaucracy. Waiting for a paper to be filled is like waiting for a train, and it’s also a place of refugees. People were sent to Nazi prisons from there, Algerians were gathered there, so it’s a place of great sorrow. Of course, my film has a lot of sorrow too, so the location infused a lot of realism into the film.34

The Gare d’Orsay, Paris, circa 1900

The interiors of the Gare introduced another distinct architectural element to Zagreb’s Modernism and its Austro-Hungarian monumentality. Welles later explained, “I wanted a nineteenth-century look to a great deal of what would be in fact expressionistic”.35 Because of the Gare’s glass ceiling, the scenes had to be shot at night.36 The near-abandoned station provided a variety of useful spaces. Here Welles created the advocate’s office, various waiting rooms, and the interior of the cathedral. Welles dressed these settings with bureaucratic detritus – files, papers, old books, even the wet washing of the accused.

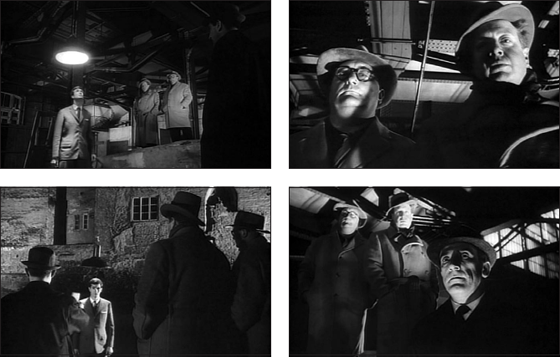

Welles freely combined shots filmed inside the Gare with footage from the streets of Zagreb, even within the same scene. Immediately following his brief attendance of a concert inside the Croatian National Theatre, K. is led by the investigator out of the concert hall to meet his future executioners. On the way he passes from the concert hall’s lobby into a labyrinthine passageway filmed inside the Gare. The executioners wait for K. inside one of the Gare’s dark and claustrophobic industrial rooms. In the reverse angle, however, K. appears standing in an open street. The spatial relations of the characters are maintained by their positions and the prop of the hanging lamp above K.’s head.

Welles’s imagined city is nightmarish yet palpable. Brimming with cinematic invention, The Trial has remained underrated within Welles’s body of work.

NOTES