Among the films commercially released during Welles’s lifetime, Spain appears as a setting only in parts of Mr. Arkadin and F for Fake, and as a travel destination in two relatively obscure television documentary series. This group of films does not comprehensively communicate the profound significance of Spain across decades of Welles’s creative life; a fuller appreciation can only be reached by examining his numerous unfinished or unproduced projects. Although he often located the action of these films in the pastoral countryside and the village, Welles also frequently filmed, or planned to film, Spanish cities – particularly Madrid, Seville, and Pamplona.

The setting appeared early on, long before Welles had the opportunity to film on location in the country. Sometime in the mid-1940s Welles developed a film based on Prosper Mérimée’s Carmen (1845). There seem to have been alternative conceptions, one set in Latin America and another retaining the original Spanish settings – the Upper Andalucian sierras, the Basque Country, Cordoba, and Triana, the Gypsy quarter of Seville, where Welles had lived for a spell the century after Carmen.1 Welles sent a Spanish-set treatment written by Brainerd Duffield to Columbia Pictures studio head Harry Cohn, appending a note promising “not the operatic dilution, but the original melodrama of blood, violence, and passion”.2 Although Welles’s Carmen never went beyond pre-production, Rita Hayworth co-produced her own version, The Loves of Carmen (Charles Vidor, 1948), without her by-then ex-husband’s involvement.3

Mérimée’s Carmen was an early classic of the españolada form, a folklorish vision of Spain populated by familiar characters and a range of melodramatic actions rooted in the stasis of a feudal, patriarchal, and superstitious society.4 Years later Welles claimed to “hate anything which is folkloric”,5 so it’s intriguing to imagine how he would have renovated the source text.

In addition to providing colourful story material for European opera and operetta, the españolada was exploited by Hollywood in adaptations of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s bullfighting novel Blood and Sand (Fred Niblo, 1922; Rouben Mamoulian, 1941), Rudolf Friml’s operetta The Firefly (Robert Z. Leonard, 1937), and The Adventures of Don Juan (Vincent Sherman, 1948). The form had been propagated at home in early Spanish cinema in films such as Florián Rey’s Nobleza baturra (Nobility of the Peasantry, 1935) and Carmen, la de Triana (1938). In the Franco era such “nostalgic and uncritical recuperation of the past” proved politically useful, even as the españolada form was ridiculed within Spain; see, for example, Luis García Berlanga’s comedy ¡Bienvenido, Mister Marshall! (Welcome, Mister Marshall!, 1952).6 But the old stereotypes died hard. Spain’s supposed cultural timelessness licensed Hollywood films to blend the folkloric and the contemporary in films such as The Barefoot Contessa (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1954).

In 1953 Welles visited Spain for the first time in two decades.7 Ernest Hemingway, another public opponent of the Franco regime, also came back to see bullfights and visit the Prado. Hemingway later rationalised:

I had never expected to be allowed to return to the country that I loved more than any other except my own and I would not return so long as any of my friends there were in jail. But in the spring of 1953 in Cuba I talked with good friends who had fought on opposing sides in the Spanish Civil War about stopping in Spain on our way to Africa and they agreed that I might honorably return to Spain if I did not recant anything that I had written and kept my mouth shut on politics.8

In 1954 Welles shot part of Mr. Arkadin in the city of Segovia. He used the exterior of the Alcázar de Segovia as Gregory Arkadin’s Spanish residence (“Well, that’s a castle in Spain for sure!” notes Guy Van Stratten). Arkadin’s masked ball, much of it clearly shot in a studio, featured costumes based on the art of Goya.

Although Arkadin’s brief depiction of Spain is merrily unrealistic, the film avoids the obvious folkloric clichés. Welles would continue to explore his own personal vision of Spain for the rest of his career.

Welles lived with his third wife, Paola Mori, and their young daughter, Beatrice, in Aravaca near Madrid between about 1963 and 1968, the period of filming Chimes at Midnight and The Immortal Story.9 He seemed cautious about flaunting his Spanish residency except for a period in the summer of 1966 when he was following the season of corridas, shooting yet more parts of Don Quixote in Pamplona, and pitching a bullfighting film called The Sacred Beasts. The Welleses relocated to England in 1968, although they did not yet sell their Aravaca residence. Part of that house caught fire in August 1970, while the Welleses were absent, and some of Welles’s documents and possessions were destroyed.

Mr. Arkadin: The Alcázar de Segovia and the masked ball

* * *

Welles had visited Spain and France to film episodes of Around the World with Orson Welles in early 1955, shortly after his loss of editorial control on Mr. Arkadin. His ambitious agreement with Associated-Rediffusion called for twenty-six half-hour television episodes, an opportunity to renew his cosmopolitan public persona in a new medium. But in October Welles broke his contracts and departed Europe without notice. Associated-Rediffusion completed and broadcast the material as a six-part series. Another episode on the Dominici murder case near the village of Lurs, France, was not completed, possibly due to censorship concerns; it was reconstructed as part of a documentary in 2000.10

The series as it was broadcast represents an innovative development of Welles’s ‘first person singular’ approach for the medium of television, a technique that would mature by the time of F for Fake. He conducted interviews on location, but his responses in counter-shot where obvious reshoots; he also tended to restructure the conversations in the editing room.11 In 1958’s Viva Italia (aka Portrait of Gina), an unshown television pilot made in much the same energetic style as Around the World, the editing recasts interview subjects such as actor Rosanno Brazzi as agreeable commentators on what edges close to a Welles monologue.

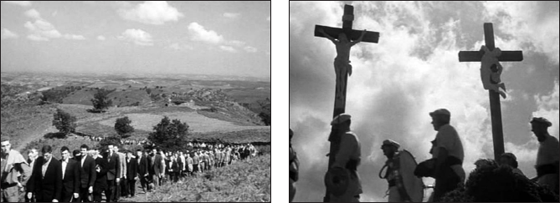

Two episodes of Around the World focus on the “contented, grounded Basques, who have lived for centuries satisfied in a static, agrarian society”.12 The village of Ciboure, legally in France, had preserved the Basque language and culture. The documentary allowed Welles to again ridicule the political fiction of national borders by celebrating the endurance of a culture that predated the French and Spanish nations and straddled the territory of both. It also gave Welles another opportunity to celebrate an Arcadia, an idealised pastoral counterpoint to the corruptions of modern urban life. In fact, the sequence of a procession of Basques through the hills almost exactly resembles in its framing shots in the staged funeral Welles filmed thirteen years earlier in the fishing community of Fortaleza, Brazil, but was never able to edit.

Throughout the episodes Welles praises the Basque village’s isolation from the mania for technological progress but, ever the inclusive diplomat, is at pains to avoid offence: “If we appreciate the Basques,” he says, “it doesn’t depreciate what is often called the ‘American way of life’.” Welles admires the Basques’ independent attitude, joie de vivre, and stoicism during the recent war. But only his charisma and enthusiasm offset a tendency to infantalise the Basque people, particularly in some of his ‘interviews’ with the welcoming villagers.

‘Pays Basque I (The Basque Countries)’, Around the World With Orson Welles (1955)

‘Four Men on a Raft’ in It’s All True (1942)

Welles with a Basque couple

One of the episodes features a conversation with Lael Tucker Wertenbaker, an expatriate American writer raising a son in Ciboure. Wertenbaker is motivated by a belief that “what we need are intervals – all of us – in backwaters”. Although education is much more demanding than in the United States, in Ciboure the children are “kings of their kingdom” and free of “mechanical aids to amusement”. In his counter-shot Welles nods and opines:

An aid to amusement seems to me to be at the centre of a great part of the moral crisis that we’re faced with all over the world now. I don’t think we need aids to amusement. I think we have to amuse ourselves.

He also tells Wertenbaker:

I don’t think progress and civilisation go together particularly… I think if you move forward you are not very likely to be civilised in the process and the most civilised countries are likely to be those where progress is not considered a very important preoccupation. And I think it’s awful good for a kid – and awfully good for us, too – occasionally, to get away from those areas where moving somewhere and getting something done seems to be more important than living in a certain way and being a certain thing.

Despite his diplomatic disclaimers, it’s difficult not to read this as a statement that civilisation is lacking in progress-mad America. But neither does he grant Basque society that status. Wertenbaker makes a summary statement that the Basques are “proud of their past, and they’re easy in the present, and they’re not afraid of the future”. Welles calls it “a beautiful phrase and a wonderful formula” but criticises part of it. The Basques may be easy in the present, he allows, but “very few civilised people are”. He explains: “I don’t think the Basques are totally civilised in the pure sense of that word, because civilisation does imply city culture, by definition, and these people don’t have a city culture.”

Welles also disagrees that the Basques have any justification to be “proud of their past”, because despite their longevity they’ve not “done a lot. You can only be proud of your past if … you’ve built a pyramid or have a library full of books to show for your past.” Welles probably didn’t read Basque fluently enough to come to this final conclusion on its literature, and was ignoring obvious figures such as Maurice Ravel, a Basque composer born right there in Ciboure. But the fact that the Basques had created a culture of their own, which endured despite decades of official repression, is almost beside the point. In many ways the Basque episodes say more about Orson Welles in the mid-1950s than they do about the Basques. The Spanish documentary Orson Welles en el país de Don Quijote (2000) concludes:

In front of Welles’s camera, the Basque country of the 1950s became transfigured into a curious mix of mythological nationalistic imagery and the rural folkloric fantasy used by the Franco regime to try to hide the complex reality of these lands. […]

Orson Welles toured Spain from the perspective of an Anglo-Saxon Hispanist, who with liberal progressive convictions tried to delve into the traditions that fascinated him while accommodating the reality appearing before him to the view he himself formed of the country.13

It’s true that Welles’s introduction of critical nuance to his otherwise celebratory picture of life in the Basque country upsets the easy clichés of the television travelogue. Becoming a Basque may not be a plausible option for the modern city-dweller, but to seek “an interval in a backwater” is a most welcome antidote to the forward-looking obsessions of modernity. Both Welles and Wertenbaker value Ciboure as a pastoral retreat, a place free of both progress and civilisation, an escape from urban society rather than a totally fulfilling alternative way of life in itself.

Around the World finds Welles at a pivotal point in his long-term fascination with Spain – or, to be more accurate in this case, an archaic Pyrenees culture divided arbitrarily between fascist Spain and the French Fourth Republic. Just a few months earlier in Paris he had made the first test shots for his adaptation of Don Quixote, which would become his obsession for decades and evolve alongside changes in Spain. From now on Welles would frequently make films inside Spain.

* * *

[A] romantic strain lives on in the American character, and this finds expression in that minority among expatriates who do indeed make quite determined (if futile) efforts to participate in the social and cultural life of the country where they find themselves.

– from Crazy Weather, a treatment by Orson Welles and Oja Kodar, circa late 197314

Ernest Hemingway had vividly communicated his personal appraisal of Spanish culture in novels, non-fiction books, and journalism. In 1932, the year before Welles’s brief spell training as a torerito in Seville, Hemingway published Death in the Afternoon, his now classic book on bullfighting. Although widely mocked by Spaniards during his lifetime for his pretentions to the status of cultural authority,15 Hemingway served as a popular explicator of Spain for the English-speaking world. In his fictional protagonists and his ever-more frequent media appearances, he also created the prototype for the macho expatriate American aficionado. Of Hemingway and the corrida, Welles later joked, “He thought he invented it, you know.”16

In Welles’s telling, their first encounter, during the recording session for The Spanish Earth in 1937, was marked by Hemingway’s easily provoked homophobia and his blustering machismo. They seem to have later mixed in the same social circles in Venice in the late 1940s and in Paris in the late 1950s.17 And even if in retrospect Welles dubiously claimed Hemingway as “a very close friend of mine” – he said he was “enormously fond of him as a man” for his humour – Welles’s public expression of his Spanish enthusiasms departed in significant and critical ways. Welles’s celebration of Spain was open and inclusive, typical of his cosmopolitan persona. Hemingway invited his readers to share his contempt for foreigners of less serious afición or for those who deviated from his code of stoic machismo. By 1959, in declining physical and mental health, Hemingway was trailing an entourage of sycophants while reporting on the bullfighting season for the mainstream American media. “I never belonged to his clan,” Welles explained, “because I made fun of him. And nobody ever made fun of Hemingway.”18

Welles was interested in types of courage beyond macho physical posturing. In 1981 he told students at UCLA that he valued bravery above all other virtues, but insisted, “don’t call me a macho, that’s not what I’m talking about”.19 Nevertheless, he saw bullfighting at its best as an exhibition of bravery, and remarked that “it’s always rewarding to observe this rare commodity in action”.20

A further distinction was that Welles proved capable of self-criticism and re-evaluation of his Spanish enthusiasms, particularly in relation to the corrida. He said in 1974:

I’ve turned against it for very much the same reason that my father, who was a great hunter, suddenly stopped hunting. He said “I’ve killed enough animals and I’m ashamed of myself.” […] Although it’s been a great education to me in human terms and in many other ways, I begin to think that I’ve seen enough of those animals die. […] Wasn’t I living second-hand through the lives of those toreros who were my friends? Wasn’t I living and dying second-hand? Wasn’t there something finally voyeuristic about it? I suspect my afición. I still go to bullfights, I’m not totally reformed, and I can’t ask for the approval of the people who have very good reasons to argue about stopping it.21

Welles’s growing disdain for the voyeuristic American macho in Spain had found expression in a string of related projects: The Sacred Beasts, The Other Side of the Wind, and Crazy Weather. But none of these projects – nor the Spanish-set Don Quixote, Mercedes, The Dreamers, or The Big Brass Ring – reached cinema screens. Neither were Welles’s earlier Spanish television documentaries broadcast outside Europe. Yet while Welles’s vision of Spain had none of the public visibility of Hemingway’s, it can be traced in Welles’s surviving papers and unfinished films as a long-term critical engagement. That vision informed how he came to reimagine Spanish cities in his work.

* * *

Welles claimed to be that rare aficionado more interested in bulls than bullfighters. In the season of 1966, when interviewed by the novelist James A. Michener in Seville, Welles explained:

What it comes down to is simple. Either you respect the integrity of the drama the bullring provides or you don’t. If you do respect it, you demand only the catharsis which it is uniquely constructed to give. […] What you are interested in is the art whereby a man using no tricks reduces a raging bull to his dimensions, and this means that the relationship between the two must always be maintained and even highlighted. The only way this can be achieved is with art. And what is the essence of this art? That the man carry himself with grace and that he move the bull slowly and with a certain majesty. That is, he must allow the inherent quality of the bull to manifest itself.22

Norman Foster’s abandoned ‘My Friend Bonito’ aside, Welles first put a corrida on film for another 1955 episode of Around the World. In ‘Spain: The Bullfight’, Welles strides like a giant through the milling crowds outside Las Ventas in Madrid. He made insert shots in a studio that recreated his arena seat, from where he pretended to observe and film the action close to the alley ringing the arena.23 When Welles abandoned the series, writers Kenneth Tynan and Elaine Dundy were subbed in to pad out the too-short episode with an introduction and commentary.24

Compared to his stylistically inventive television travel documentaries of the 1950s, the nine episodes of In the Land of Don Quixote are conventional and largely tedious, and much less effective for the lack of Welles’s first-person presence as presenter and narrator. Welles exploited this commission from RAI in Italy as another piggyback ride for the ever-evolving Don Quixote and reportedly dismissed the series as “just a travelogue”.25 These silent 16mm movies of Welles’s family on vacation are not particularly successful even in that undemanding genre, despite their extensive view of the cities of Spain. Welles shot material in Madrid, Seville, Pamplona, Córdoba, Cádiz, Gibraltar, Algeciras, Granada, Ronda, Guadix, Jerez, Toledo, Aranjuez, Alcalá de Henares, Ávila, and Segovia.26 His executive producer Alessandro Tasca di Cutò recalled, “We had no script other than the one in his mind, and his idea of how he would assemble it in the cutting room.”27

Welles worked on the editing at his wife’s family villa in Fregene outside Rome.28 His original material was supplemented by stock footage from the archives of NO-DO, Franco’s propaganda newsreel service.29 Individual segments within the episodes are divided by a repeated shot of a Quixotic windmill accompanied by a flamenco guitar punctuation. Most of the music was provided by the young virtuoso Juan Serrano.

Welles’s notes indicate he planned to use bullfighting as the unifying theme of the series. In June 1961 he explained to an editorial assistant who was compiling reels of usable footage:

The idea is not to do a single programme on bullfighting, but to use this theme in several of the programmes as we follow the different ferias. Following the ferias gives us an excuse to see the different towns and to examine the aspects of Spanish character and countryside.

Bullfighting and its rituals are indeed prominent in the broadcast version, although the ultimate significance of each corrida is sometimes obscure within the casual assemblage and minimal commentary. Welles explained to the editorial assistant, “I just have a lot to say about bullfighting in general and in particular, and will use the best of the material to illustrate my remarks,”30 but in the end RAI commissioned another writer to provide an Italian narration that was voiced by actor Arnoldo Foa. It is unclear to what extent RAI tampered with Welles’s edit, although Tasca di Cutò called the final product a “flat, distorted ghost of the original”.31 Juan Cobos, the assistant director of Chimes at Midnight, said, “I cannot imagine that [Welles] ever approved the final cut that was shown on RAI-TV in 1964. I think he only partially cut the series, and he certainly didn’t want the spoken narration that was used.” Welles attempted to import the negative back into Spain later in the 1960s to reedit and record a narration but was impeded by Spanish bureaucracy.32

Left-wing critics in Italy at the time of original broadcast criticised Welles’s lack of political engagement with the political situation under Franco.33 During the filming Tasca di Cutò encountered Franco in person at the Seville feria and was given permission to film the dictator, but the material did not make the series.34 The series expresses an American tourist’s point of view unlikely to have offended the regime or to have contradicted the folkloric image of Spain the dictatorship promoted to the world. In comparison to Welles’s later Spanish explorations, In the Land of Don Quixote is without much depth. Nevertheless, one city sequence rises above the mundane and is worth examining.

* * *

Hemingway had made the fiesta of San Fermín famous in the English-speaking world with The Sun Also Rises (1926). Back in 1923 he had reported to the Toronto Star: “As far as I know we were the only English-speaking people in Pamplona during the Feria.” The encierro or ‘running of the bulls’, “the Pamplona tradition of giving the bulls a final shot at everyone in town before they enter the pens”, had “been going on each year since a couple of hundred years before Columbus had his historic interview with Queen Isabella in the camp outside of Grenada”. Hemingway claimed the amateur fight following the encierro created “a casualty list at least equal to a Dublin election”.35

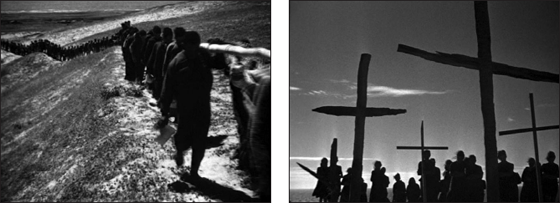

It has been said, probably apocryphally, that tickets for the 1961 fiesta sat on Hemingway’s desk in Sun Valley, Idaho, on 2 July, the day he took his own life with a shotgun. That summer’s fiesta began just four days later. Unless he relied entirely on a second-unit crew, Welles was on location in Pamplona, historical capital of the Basque country, to film the encierro for an episode of In the Land of Don Quixote. The coincidence of these events has been little noticed, but Hemingway’s suicide had a profound effect on Welles’s subsequent work. He used the date of Hemingway’s suicide for the date of Jake Hannaford’s death (and seventieth birthday) in The Other Side of the Wind.36

The episode about the encierro of San Fermín is also one of the few parts of the travelogue series to have inspired Welles’s creativity.37 Cobos, who reports that Welles incorporated some stock footage, agreed that “here you can see him at his best on the editing room”.38

The structure of the encierro episode suggests a revival of the spatial conceit of Welles’s unrealised samba sequence in ‘Carnaval’, the mapping of a city by illustrating human movement from the periphery to the centre in the context of a mass cultural ritual.

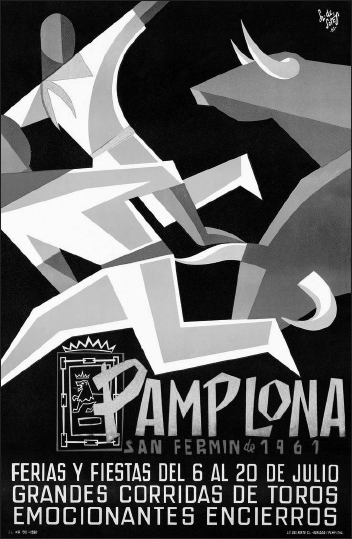

In the encierro episode, three loose stages lay out a trajectory from the countryside to the city of Pamplona. The first begins with images of ancient paintings of bulls in the caves of Altamira. This is followed by footage of bulls chased, corralled, and branded on ranches, in encounters with humans in small rural bullrings, and marched through the countryside. The second stage depicts an encierro through the streets of a provincial town. Runners scramble to safety by hoisting themselves onto the grates of windows or ward off angry bulls with chairs. In the amateur fight in the Plaza de Toros, men are knocked aside and thrown, dozens of women face the bulls, and a range of spectators gawk with voyeuristic pleasure from the safety of their seats.

The third stage is the longest: the encierro of San Fermín. It’s a stunning and terrifying montage lasting six minutes. The sequence has been too long obscure, buried within the nearly four hours of this generally unremarkable series. If not as magnificently realised as the Battle of Shrewsbury in Chimes at Midnight – its technical limitations are considerable by comparison, and the many clumsy edits and sound mix give the impression the sequence was never actually finished – it shares a little of that sequence’s energy and violence.39

At the launch of a rocket flare, the bulls are released from their corral. In the rush several bulls knock each other over and slide on their backs before again finding their feet. Men are lifted by the horns, thrown aside, trampled underfoot. Welles creates a moment of macabre comedy by cutting away from a bull’s charge on a fallen man to a pair of nuns observing from the safety of a high window. The soundtrack is repetitive drumming and dubbed-in human screams.

The density of the crowd mounts as it nears the entrance to the Plaza de Toros. Finally the charge compounds into a mass of bodies blocking the entry. The bulls leap and scramble across the writhing human mass. Welles explores an innovative visual concept by intercutting the live-action footage with dynamic still photographs. The stills pause on moments of fear or pain, when runners are crushed in the crowd or meet the horns of a bull. The camera either roves across these photographs or cuts to small details. Guitar music punctuates the drumming during these interpolations.

Scenes of the encierro at the Fiesta de San Fermín in Pamplona (In the Land of Don Quixote)

One man died in the event that year, and Welles unflinchingly depicts on screen the exhilaration and violence of an old Spanish ritual that had become, thanks to Hemingway’s writings, a major international tourist attraction. Welles’s documentary reconstruction neither romanticises nor particularly criticises the encierro. But by beginning the episode with images of the Altamira caves he entrenches the ritual in ancient Spanish traditions. Welles emphasises the majestic natural force of the bulls, the fear they provoke, in images of raw nature flooding the streets of the city of Pamplona.

* * *

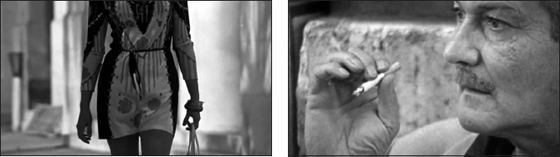

Still photographs used in the encierro sequence (In the Land of Don Quixote)

Barely a month after Hemingway’s suicide, columnist Leonard Lyons reported in the Hollywood Citizen News that Welles was at work on a screenplay about a bullfighter that was probably an embryonic version of his project The Sacred Beasts.40 This script seems to be Welles’s first cinematic attempt to interrogate American interest in Spanish culture.

Welles explained the project to documentarians Albert and David Maysles in the summer of 1966:

It has to do with a kind of voyeurism, a kind of … emotional parasitism. And it has to do with the whole mystique … of the he-man. This picture we’re going to make is against he-men.

[It’s about] the people who go to bullfights not occasionally as tourists do but who are passionately addicted to it as aficionados. That part of the aficionados who have the Hemingway mystique, who got hooked through Hemingway. And our story is about a pseudo-Hemingway. A movie director who belongs to that league that in Spain they call the macho … a fellow that you can hardly see through the bush of the hair on his chest.41

Welles’s project evolved, lost its bullfighting background, and transplanted its drama to Los Angeles, where it was shot as The Other Side of the Wind. Nevertheless, the theme of American aficionados in Spain did not recede from Welles’s interest but reappeared in Crazy Weather, an unmade treatment project of the early 1970s.42 Oja Kodar remembered she began writing the story, and “whenever something had to do with Spain, [Welles] wanted to be involved … he managed to introduce something about bullfighting into the story although I hated bullfighting.”

Kodar admitted that no ending was ever written. The surviving draft is a consistently numbered 144-page composite combining treatment and formatted screenplay material, often with variant versions of the same scenes and some missing parts. References within that draft date it to late 1973. Kodar remembers collaborating on the project in Paris while Welles was editing parts of The Other Side of the Wind.43 This would have been prior to his return to the USA to film John Huston’s performance as Jake Hannaford.

Like The Sacred Beasts, Crazy Weather is a scathing attack on he-men, American ignorance, and cultural appropriation. There is also a new emphasis on women’s subjective experience of urban space. The story centres on a love triangle. Welles and Kodar introduce Jim Foster, one of those romantic Americans who make “quite determined (if futile) efforts to participate in the social and cultural life of the country where they find themselves”.

He lives and works in Spain, and he’s fallen head over heels with everything Spanish… Spain has a very strong appeal for his sort of American; their special vision of the so-called Spanish way of life seems to combine the prestigious dignity of an antique civilization with something of the tense simplicity of a good cowboy movie. Jim Foster never read Mérimée, but he’s well-grounded in Hemingway – a key to his character, he cherishes Spain as a ‘man’s country’. […]

The corrida has never had so many fans among non-Spaniards. Hundreds of foreigners follow the bulls with studious enthusiasm from the beginning to the end of one temporada after another. Jim, of course, is one of these.44

Despite his Spanish wife and years living in Spain, Jim speaks only “limited and rather stilted” Spanish.

The key setting is an unnamed provincial town on the road to Madrid where Jim and his wife, Amparo, plan to attend a corrida. Amparo, driving towards the town, accidentally injures a nameless foreign youth with her car and offers him a lift. The boy’s arrogance and aggressive sexuality disrupt Jim and Amparo’s marriage. He taunts Jim about his misogyny and flirts with Amparo. Along the road Jim is forced to hike to a filling station to replace gasoline the boy has intentionally drained from the tank. The boy later sabotages the car’s tyres. It’s an open question whether Amparo and the boy committed adultery on the banks of a river. After driving Jim to the point of rage, the boy exits the car and limps off alone.

When the couple arrive in town, Jim gets out at a motel bar to drink Scotch. Amparo drives on alone towards the Plaza de Toros in the town’s outskirts and is overwhelmed by traffic. The treatment focuses on Amparo’s dazed experience of the street celebrations of the feria, a ritual that had been depicted with touristic detachment in In the Land of Don Quixote.

In F for Fake’s ‘girl-watching’ title sequence, Welles made gentle mockery of men leering at Kodar as she walked through a city during summer. That sequence was shot in Rome circa 1969 for “quite another film” – probably Orson’s Bag – but incorporated into Welles’s essay film around the same period he and Kodar wrote Crazy Weather.45

In that ‘girl-watching’ sequence Welles turns the camera’s gaze back on the observers. By contrast, Crazy Weather’s treatment, sketchy as it is, suggests an approximation of Amparo’s subjective encounter with the spaces of a town, her encounter with its heat, dust, and crowds, while in emotional distress. Apart from George’s brief ‘last walk home’ in The Magnificent Ambersons, approximations of subjective experience are rare among Welles’s realised city sequences.

The boy accosts Amparo outside the Plaza de Toros and insists on using Jim’s ticket. Amparo acquiesces, and then finds herself crushed by the mob. She is forced against the boy:

F For Fake

It takes the two in a sort of huge embrace, holding them tightly against each other… If before she’s had any thought of resisting, it’s too late… The crowd is acting as the boy’s accomplice, cutting off all possibility of retreat, forcing a prolonged physical intimacy. […] The narrow arched corridor inside the Plaza is jammed to suffocation – to near paralysis – by a steaming mass of humanity crammed so densely together that the effect is not so much of numbers as of a single heavy-breathing beast.46

Meanwhile, Jim has a cornily macho response to his wife’s possible infidelity, which he later admits to her. His voiced-over confession presents a flashback to his meeting with a young tourist – “as dumb a female as ever came out of Germany”, the treatment notes. With “the considerable stimulant” of the “mounting allegria in the streets”, he takes her on a carousel ride. The boy appears in time to join the couple, and Jim broods with anger at how he has been made to feel middle-aged in their company. The boy, however, assumes “a certain vague air of the pimp” and leads the couple to the girl’s tent in an open hippie camp field outside the town. Then he leaves them alone.

Later, somehow wounded by a bull’s horn – the treatment’s continuity is lost by this point – the boy criticises Jim’s Spanish fetish with a frankness that is remarkable considering Welles’s earlier television documentaries: “He’s got these picturesque notions, and a mind like a post-card. For good old Jim, Spain is granddaddy’s land. The clock stopped here somewhere in the middle of a Victorian novel…”47

Crazy Weather joined the many other Welles projects of this period that were developed but never produced. The Other Side of the Wind, almost completely shot but not fully edited, descended into legal entanglements that were not resolved during Welles’s lifetime, and Welles’s exploration of the Hemingwayesque figure remained unseen. Yet Spain remained a setting in at least four additional works-in-progress towards the end of Welles life: early incarnations of Mercedes (aka House Party), a new essayistic conception of Don Quixote, The Dreamers, and The Big Brass Ring.

* * *

In 1961 Welles had gone to Seville to shoot the April feria for two episodes of In the Land of Don Quixote. In addition to more bullfighting scenes, including the graphic goring and tossing into the sand of a torero, Welles filmed the city in moving shots as the family Mercedes crawled through the narrow streets of the city (the accompanying music in the broadcast version is Bizet’s “operatic dilution” of Carmen). The family visit the Plaza de España and the Casa de Pilatos, Seville locations that would in the coming months double for parts of the Middle East in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962). In another scene Welles and Beatrice drive a horse-drawn cart into the Barrio de Santa Cruz, the traditional Jewish quarter, to the accompaniment of flamenco music.

Seville returned as an imaginative setting at the end of Welles’s career in the screenplay of The Dreamers. It is a much more ambitious adaptation of Isak Dinesen’s work than The Immortal Story, which had been restricted to four speaking parts, Mr Clay’s house, and the largely empty streets and colonnaded squares of Welles’s imagined Macau. That said, The Dreamers continues Welles’s faithful embrace of Dinesen’s sombre aesthetic and her vague mid-nineteenth-century settings.

The screenplay, written in collaboration with Kodar in the late 1970s, combines ‘The Dreamers’ and ‘Echoes’, two Dinesen tales about the character Pellegrina Leoni. With its frame story set off the coast of Africa, ‘The Dreamers’ has been described as “a curious cultural inversion of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” in which European events are related as an exotic tale to its African and Arabic listeners. The cinematic potential had already been recognised: Truman Capote had wanted to make it with Greta Garbo.48

Dinesen established a structure of flashbacks within flashbacks. In the Welles-Kodar adaptation, a man named Lincoln tells the Pellegrina story on “a full moon night in 1870” on a dhow headed for Zanzibar. He recalls how in 1863 he met two other abandoned lovers of Pellegrina by coincidence at an inn on a high mountain pass in winter. They each tell the others a story of their obsession for a vanished lover. They conclude they have all loved the same woman. What’s more, Pellegrina promptly arrives at the inn with her Jewish “shadow”, Marcus Kleek – a breathtaking moment of dreamy illogic anticipated by one of the lovers. They chase after her through a snowstorm. She leaps from a cliff. As Pellegrina lies on her deathbed at a nearby monastery, Kleek recalls her history: she had been an opera star who had lost her voice when a theatre in Milan caught fire during a performance. Presumed dead, she abandoned her identity. The loyal Kleek followed, watched, and provided for her when it was necessary. She moved to a village in the mountains, and fell slowly in love with a young boy, Emanuele, her singing student, until cast out as a suspected witch (this village episode is the plot of ‘Echoes’). Pellegrina then set out to wander into “the great world of cities and men”. Changing her name as she pleased, she took and abandoned many lovers. And then we learn that one of the young monks in the monastery where she lies dying is Emanuele.

Welles in Seville, 1961 (In the Land of Don Quixote)

The screenplay relocates parts of the Pellegrina story to cities of autobiographical significance to Welles, personalising what is an otherwise faithful adaptation of the two tales. In Dinesen’s story, Lincoln’s hunt for Pellegrina takes him from Rome to Basel, Amsterdam, and finally the Alps. The screenplay makes this a brisk Arkadinesque journey through Santiago de Compostela, to Amsterdam, Dresden, Odessa, Prague, and then the Venice Carnival, where Lincoln encounters Donna Lucetta Boscari, “notorious from Vienna to Palermo, expert in poisons and aphrodisiacs, procuress to the higher clergy”. According to Kodar, Jeanne Moreau might have starred as Donna Lucetta.49 Welles had filmed documentary footage of the Venice Carnival back in 1969, possibly for incorporation into Orson’s Bag, but his interest in Venetian masques dates back to his attendance of the Beistegui ball in 1951.

The Roman scenes in Dinesen’s story, where Lincoln first meets Pellegrina, are moved to Triana in Seville. Welles stirred in a sizeable helping of Merimee’s Carmen. Welles makes Pellegrina’s character the daughter of a Spanish baker whom one character describes as having “a little bit of gypsy phosphorescence”.50 In the sierras of Andalucía, Pellegrina wears riding clothes “still unchanged since Goya”.51 Dinesen, however, who felt a kinship with Pellegrina, once described her in terms of another Spanish archetype long familiar to Welles – she was a “Donna Quixote”.52

In the Land of Don Quixote had presented several panoramic shots of Seville, and Welles evidently intended to return to this vantage to film the cityscape for The Dreamers. Lincoln is said to observe Seville “as though all of Spain were laid out under his feet”. His narration remarks: “It seemed to me that I might lift the very tower of the great Cathedral in Seville between my two fingers.”53 In the Dinesen story he fantasises it is St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. A Carmenesque version of mid-nineteenth-century Seville is palpably evoked by the script, with occasionally specific ideas for visuals. The first image was to have been the naked silhouette of Pellegrina through the window of a Triana brothel, juxtaposed ironically with a male voice singing a saeta to a Madonna in a Holy Week procession. Lincoln remembers “the many smells there in that street… If ever I were to smell them again, I’d feel that I’d come home.”54 But as their romance progresses, he glimpses the ever-observant Kleek “at the far end of the street … a tall figure all in black [who] stands motionless in the shadows”55 – a very Wellesian image. Pellegrina soon vanishes.

Struggling to find funding for this ambitious project, Welles shot several scenes at his home in Los Angeles between 1980 and 1982. He played Kleek and cast Kodar in the role of Pellegrina. Gary Graver, a young and selfless collaborator in this period, was the cinematographer. The scenes have survived and have been posthumously assembled for screening by the Munich Film Museum.56 Despite the poverty of their making, they are beautiful fragments of one of Welles’s final unfinished works.

* * *

By 1974 Welles was despairing of the modernisation of Spain:

In the last six months it’s joined the glory of the present world to such an extent that you don’t know whether you’re in Los Angeles or not in half the streets in Madrid. And a great deal of the grace and the pleasure of life, at least in the big cities, is gone.57

Franco would die the next year, clearing the way to Spanish democracy. But rather than celebrate the fall of a regime he had opposed ideologically from its very beginning, Welles was ambivalent about the change. In 1982 he reflected, “in a curious way the liberation of Spain and the fragile democracy has rather done away with both Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and it’s a sad point I’ve got to make… Spain is losing its Spanishness.”58

Welles spoke of transforming the ever-evolving Don Quixote into an essay film on this very subject called When Are You Going to Finish Don Quixote? It was never made, but thoughts on post-Franco Spain found their way into another project called The Big Brass Ring, which he wrote at the urging of filmmaker Henry Jaglom in 1981 and 1982. Material from a story by Oja Kodar called ‘Ivanka’ was incorporated into the original concept. Welles and Jaglom set up a deal with producer Arnon Milchan but were unable to find a star actor willing to play the lead role for a fee of two million dollars.59

The Big Brass Ring is both a half-serious political thriller and another Arkadinesque romp. It concerns the friendship between Blake Pellarin, a US senator and as-yet failed presidential contender, and his political mentor, Kimball Menaker, a former Roosevelt advisor and Harvard professor whose homosexuality has been publicly exposed.

Recovering after the election of Ronald Reagan, Pellarin is letting his beard grow while sailing off the coast of North Africa with his wealthy wife, Diana. When he catches Tina, a Brazilian manicurist, stealing his wife’s emerald necklace, he decides in a rash moment to help her fence it. He vanishes into Africa to seek Menaker’s help. Diana, who desperately wants to be First Lady, marshals a team of flunkeys and intelligence operatives to track down her husband and keep tabs on his activities. At the airport in Tangier Pellarin is accosted by the famous journalist Cela Brandini, who has just interviewed Menaker as background research on a story about the senator.

Menaker’s present situation is even more absurd than that of the exiled Polish crooks of Arkadin. He lives in virtual captivity as an advisor to an African despot in the fictional Republic of Batunga, is guarded by two beautiful “mother-naked” black lesbians, and cares for an incontinent monkey. After securing Menaker’s help, Pellarin takes the monkey out of Batunga and onboard his yacht, which is docked in Barcelona. Alas, the monkey leaps overboard with the emerald necklace in its paws, disappearing forever into the depths and leaving Pellarin with the bizarre responsibility of finding cash to pay off the manicurist. But he persists. “I think the craziest promise is the sacred one,” Pellarin explains to Menaker, who joins him in Madrid.

Spain is marching into European modernity. Menaker hears that the “paint [is] peeling off the Goyas” at the Prado because of the smog. Old cafés have become banks, even as the Gran Via’s “nineteenth century eccentricities” still show “their silhouettes against its pallid sky”.60

Menaker’s romantic history is recalled in the memory-haunted spaces of the Retiro park. There the men will pay off Tina through her brother (Tina has not been allowed to enter Spain). Pellarin arrives at the park with a briefcase of cash. In an unpublished alternative version of the script in the form of a novella, Menaker instructs Pellarin to meet him at “the equestrian statue of some forgotten Spanish hero”. Pellarin doesn’t find it, and only after enquiries does he discover that “the statue has been gone for almost forty years”.61 In the script, Menaker is hiding behind a bush, captivated by the sight of a homeless young man asleep on a park bench. The man reminds Menaker of his crippled lover Vanni, who “caught it not far from here” more than forty years earlier in the Civil War.62 Vanni was seriously wounded but lived on for decades in Florida as an invalid.

The Civil War comes back to life with this memory trigger. Menaker recalls to Pellarin that Madrid was the “first city that was ever bombed. And how the world was shocked. In those days we were innocent. We still believed mass murder from the skies was quite a sin.” During the war “you could take a street car to the front line. But not the subway – on the subway you could end up on the wrong side.” Menaker was staying at the Gran Via Hotel alongside “Malraux, Ehrenberg, Dos Passos”, waiting for his fighting lover to return. He pointedly notes twice that “Hemingway wasn’t there that year.”63

Menaker and Pellarin take pity on the sleeping homeless man and stuff money into his shoes. Shortly after three “tough-looking sailors” approach, but rather than make off with the cash, they wake up the young man and insist he take better care of his money. “Where on earth could that happen except here in this dumb country?” says Menaker.64

Pellarin’s romantic past comes to light in another part of the city. Nine years earlier, after a tour of duty in Vietnam, he had temporarily abandoned Diana to live with a French-Cambodian woman in Paris. The woman mysteriously vanished, and although Pellarin returned to Diana, he has obsessively searched for her ever since. But Menaker reveals he has kept in contact with the woman, and leads Pellarin to a rendezvous with her in a house, “once the home of some prosperous merchant in another century”,65 in the vicinity of the celebrations of the Verbena de San Juan.

The screenplay provides a vivid visual and aural sketch of the setting. Pellarin and Menaker’s cab passes through “canned music, loud and various, blaring out… there’s a great yelping of barkers, the clatter of shooting galleries, the clickety rattle of the wheels of fortune … the cab has moved into the glare of many lights.”

When they turn a corner, the “large, dark house blots out much of the light and baffles much of the sound … the muted growl and clatter of the Verbena Fair” is “weirdly echoed from the other side of the dark house”.66 As Pellarin prepares to enter the house, recalling his obsessive search for the woman, “the noises of the feria are muted now, melting together, like the murmur of some crazy ocean”.67 A dreamlike encounter awaits.

Pellarin enters the house and finds the woman waiting naked for him. The script is vague as to specific visual ideas: “The scene is strange, almost surreal … (the action must be given in synopsis … The climax of this sequence is strong erotic: to spell out its specific details would be to risk pornography).”68

Menaker walks to the feria and rides a Ferris wheel. His passenger car passes a window of the house and he spies the couple making love. When the Ferris wheel stops its motion, Menaker’s eyes meet the naked Pellarin’s.

The mysterious French-Cambodian woman vanishes immediately after the love-making. Pellarin searches the house for her. By now he has figured out Menaker sabotaged the adulterous relationship in Paris to protect Pellarin’s presidential chances. He promptly renounces the old man to his face. Then he has another run-in with Cela Brandini, who reveals that Menaker has for years been harbouring a sexual obsession for Pellarin, which involved a semen-stained handkerchief he had sent to Vanni in Florida. In rather opaque plotting, this causes Pellarin to utter “a sudden, terrible groan” and “wander through the dark streets of the city, searching … for his friend”.69 In a state of despair, Pellarin beats a helpless blind beggar to death under a concrete overpass in a wasteland of late-Franco Modernist architecture.

In an outrageous dénouement at the Madrid railway station, the inspector of police returns the briefcase full of money Pellarin left at the murder scene and refuses to implicate this American VIP in the case. Pellarin is then unexpectedly reunited with Menaker on the rapid train. There will be no stops for six hours until they reach the French frontier. Pellarin buys a bottle of brandy and the men sing cheerfully together as the train departs.

It’s a dark and strange conclusion to one of Welles’s final projects in cinema, yet another that would not be realised beyond the page. Perhaps by way of explanation Welles ends his script with:

If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.