The pursuit of sexual pleasure – the drive, aim, object, and satisfaction, to use psychoanalytic terms – is a process that is extraordinarily diverse and individualized; it is cultural and symbolic, as well as biological, psychological, (inter)personal, and oftentimes political. As such, sexual pleasure tends to be discounted or misunderstood by health care professionals. This is especially true for alternative or “unconventional” sexual practices, which do not fall within the realm of traditional “vanilla” sex. One example of alternative sexual practices is BDSM, which is an acronym for a broad range of sexual practices that focus on themes of bondage and discipline (B&D), dominance and submission (D/s), and sadomasochism (SM). For the most part, research in this field has been quantitative and has focused on describing the people affiliated with BDSM, while overlooking the importance of the sexual acts themselves, as well as the subjective motivations and desires of these individuals, and how these personal differences are related to risk-taking and/or risk reduction in the context of public health. These factors need to be understood in order to design and implement more effective measures for the prevention of HIV and other STIs.

Most research on this topic overlooks an essential component of BDSM by omitting a qualitative analysis of the motivations and meanings behind individual desires and how these are relevant to improving public health initiatives. This omission may in part be attributed to the fact that BDSM is considered by many to be an “extreme” sexual practice that purposely defies public health discourse, and thus indicates the tensions between public health imperatives and individual desires. Health care professionals dealing with the detection of and education on HIV and other STIs are therefore vested, along with other health care providers, with paradoxical responsibilities: to advocate for “safer sex,” while respecting patient autonomy. As agents of the state, public health officials must support and transmit dominant public health messaging while respecting personal choices and needs, as dictated by professional ethics. Yet in the current context, most health care professionals have an inadequate understanding of sexual practices, such as BDSM, that radically depart from prescribed sexual norms. As a result, public health interventions are improvised. This chapter is based on a critical ethnographic nursing study of BDSM that begins to redress this gap in the literature and point the way to culturally competent public health initiatives for those who practice alternative or “unconventional” sex.

To date, most research on BDSM has dealt with the general prevalence, demographic backgrounds, and psychological adjustment of those affiliated with BDSM. One particular area of BDSM research that has received little attention is the relationship between BDSM and the sexual risks associated with these activities, such as the transmission of HIV and other STIs. This is surprising, given that some BDSM activities potentially involve a greater level of risk for the transmission of STIs compared to more conventional sexual practices. For example, BDSM activities may involve contact with a range of bodily fluids (blood, urine, excrement) and may also involve open wounds as a result of piercing, branding, or scarification. This combination of bodily fluids and open wounds would appear to increase the risk of HIV transmission. A related area of research that remains insufficiently explored is men who have sex with men (MSM) who are involved in BDSM. Considering that MSM are currently the population at highest risk for contracting HIV (UNAIDS, 2010), and participation in BDSM activities may carry an inherent level of sexual risk, this is an important population to study in order to gain a more thorough understanding of their level of risk and the strategies (if any) they have implemented in order to protect against the transmission of HIV and other STIs.

In Canada alone, it has been estimated that the number of people living with HIV as of 2011 is 71,300; this represents an increase of 11.4% since 2008, when the estimate was 64,000 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012b). Research indicates that, of those individuals living with HIV, 76.7% are males (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012b). This is not surprising considering that sexual relations between men is the most common method of transmitting HIV in North America and Europe. As of 2011, there were 33,330 MSM living in Canada who had been diagnosed with HIV; this corresponds to 46.7% of the entire population of Canadians living with HIV (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012b) and 61.4% of all adult Canadian males living with HIV (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012a). Furthermore, it has been estimated that 47% of new HIV infections in 2011 were accounted for by MSM, compared to 44% of new infections stemming from this category in 2008 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012b). The increased risk of exposure for MSM is especially problematic because approximately 20% of MSM are not aware of their HIV status (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012b). Clearly, HIV transmission in Canada remains a challenging issue that is compounded by the influence that culture and gender roles have on attitudes toward sexuality and sexual risk-taking. Public media typically stereotype men as being sexually aggressive and more likely to take risks, including sexual ones. Consequently, MSM are often portrayed as men who engage in higher-risk activities, more often, and with more people. This characterization of MSM, especially those involved in alternative or unconventional sexual behaviors such as BDSM, may be a self-fulfilling prophecy that contributes to higher-risk sexual behaviors. Homophobia, stigma, and maltreatment have kept people with unconventional sexual interests hidden, often discouraging them from engaging in safer sexual practices, or from seeking necessary help in public health institutions (Holmes & O’Byrne, 2006). For example, since many MSM do not self-identify as gay or bisexual, they may also be more likely to engage in more unsafe sexual practices (Rofes, 1996). Due to the inherent danger of some BDSM sexual practices (e.g., “bloodsports”), it seems likely that people who have these interests but who do not seek out a BDSM venue or community, due to fear of stigmatization, may also be increasing their likelihood of higher-risk sex as many BDSM activities require at least some instruction or experience in order to minimize risk of HIV and STI transmission.

The relationship between HIV and MSM has been studied extensively for over three decades and continues to be an important area of public health research. While the rise in popularity of alternative sexual practices such as BDSM has led to new research in this field, the relationship between BDSM practices and STIs, including HIV, has received little attention. While the prevalence and demographics of people with BDSM affiliations has been studied extensively, research has not yet devoted appropriate attention to the subjective desires – and the pursuit of sexual pleasure – at play in BDSM practices. Nor has it explored the socio-cultural factors associated with MSM in BDSM venues, the potential risks of HIV and STIs transmission, or the risk-reduction strategies used by these men. Also, the role of architecture and the design of BDSM clubs and their policies, as they relate to sexual practices, is absent from existing research. For example, a study by Holmes, O’Byrne, and Gastaldo (2007) found that the architecture and design of bathhouses are factors that contribute to a better understanding of the sexual practices, risks, and risk-reduction strategies associated with a high-risk group of MSM who self-identify as “barebackers.” While qualitative research has been conducted in public sex spaces, such as bathhouses (Holmes, O’Byrne, & Murray, 2010), these institutions can differ significantly from BDSM venues in a number of ways. First, there are a number of sexual activities that are relatively specific to BDSM practices and which are associated with a potentially higher risk of transmitting HIV and other STIs, such as “fisting,” piercing, and cutting. BDSM venues also differ from bathhouses and other sex clubs insofar as BDSM practices tend to focus much more on foreplay activities (bondage, discipline, role-play, various forms of oral sex, etc.) and less on actual intercourse (Weinberg, 2006). In addition, whereas bathhouses, and some other sex clubs, often constitute anonymous sex venues, BDSM venues are typically frequented by people who are at least somewhat familiar with each other due to the tightly knit nature of many BDSM communities (Newmahr, 2008; Sagarin et al., 2009). This familiarity may actually serve as one form of risk reduction as it results in a type of classification system in which those who have acted dangerously, by violating consent, boundaries, and other established rules, are marginalized from the community (Taylor & Ussher, 2001). However, it is also possible that familiarity could increase risk, as people may be less vigilant about using condoms and other risk-reduction strategies with people who are known to them as compared to acts with anonymous sex partners.

Unlike bathhouses and other sex spaces where verbal communication is almost nonexistent, BDSM etiquette encourages people to discuss their sexual interests, what they find pleasurable, their perceived needs, physical and psychological boundaries, past encounters, health restrictions, as well as HIV and STIs status, as discussing these issues is believed to increase intimacy and pleasure (Newmahr, 2008; Taylor & Ussher, 2001). This aspect is of significant importance and deserves further exploration given that communication may be related to risk reduction, but could also result in the decision not to use condoms. New research dedicated to understanding the intricacies of BDSM practices, and how these unique factors produce or mitigate risk, will have an important influence on public health initiatives, especially in relation to the transmission of HIV and other STIs in BDSM communities.

Our ethnographic nursing study represents an innovative response to a gap in current studies of alternative sexuality and public health literature. It provides a better understanding of the motivations behind high-risk sexual practices involved in BDSM, the recognition of ways in which members of this population mitigate (or ignore) inherent risks, and the emergence of new methods of providing effective, efficient, and ethical health care interventions in public health settings. This study is highly relevant precisely because it focuses on BDSM, which often includes acts that can increase the risk of HIV transmission due to the exchange of a full range of bodily fluids (blood, semen, feces, etc.), activities that can cause open wounds (piercing, branding, etc.), and intimate interaction with other potentially high-risk MSM. Understanding the subjective meanings behind these high-risk acts will help researchers and public health professionals to understand the reasons that MSM choose to engage in them, why they may or may not employ various risk-reduction strategies, and how public health initiatives can be effectively deployed to serve this community. This study has focused specifically on men who have sex with men (MSM) in BDSM venues, and has sought a better understanding of their motivations, desires, risk-taking behaviors (if any), and risk-reduction strategies (if any), as well as to gain an understanding of the individual and collective impact of institutional (public health) power and discourse on this population. Consequently, the study’s objectives were: 1) to collect and analyze the stated motivations of MSM who participate in BDSM activities; 2) to identify potential risk factors associated with BDSM, from the participants’ personal perspectives; 3) to identify risk-reduction strategies used by MSM who visit BDSM venues; and 4) to advance the development of innovative strategies regarding higher-risk sexual practices, which take into account the desires, experiences, and personal choices of those people typically labeled as “sexually deviant.”

An exploratory research design facilitated a better understanding of the sexual practices that take place in BDSM venues, the risks that are inherent to specific BDSM activities, as well as the nature and prevalence of risk-reduction strategies. As BDSM is often practiced in specific places, and those who attend BDSM venues often form a community of their own, ethnography was selected as the methodological approach. As a study of culture, an ethnographic approach was ideal for exploring our research objectives and for better understanding a group of individuals who themselves constitute a distinct subculture. Ethnographic studies are typically divided into three categories: classical, critical, and postmodern/poststructural (Grbich, 1999). We used a mixture of critical and poststructural approaches, as we agree with Francis (2000) that “poststructuralist theory can provide a useful analytical tool for research which seeks to examine, disrupt or deconstruct discourses in nursing and healthcare” (p. 26). A critical/poststructural design proved to be a crucial component of this research because it militates against forming firm boundaries on cultural issues and thus aims to deconstruct the fundamental view that BDSM is inherently negative or “deviant,” and promotes the idea that there is no singular truth, only various perspectives of reality.

A total of 10 participants were recruited to complete a self-report questionnaire and face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Inclusion criteria were genetic (XY) male, has attended at least one BDSM venue or event, and has had at least one sexual experience with at least one man. Participants who defined their sexual orientation as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, transsexual, queer, or questioning were included in the study.

We recruited participants in three Canadian cities: Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. Toronto and Montreal were selected as these are the two largest Canadian cities in which HIV incidence is known to be the highest. Ottawa was selected because HIV transmission in this city has received significantly less attention in scientific research, despite the fact that the rates of HIV infection have been increasing. For example, as of June 2011, the prevalence of HIV among men from 20–29 was higher than it had been in the previous 10 years, and the rate of HIV in men 30–39 has also been increasing (Ottawa Public Health, 2011). Nearly two-thirds of these reported cases are accounted for by MSM (Ottawa Public Health, 2011). This ethnographic study took place in a variety of BDSM venues in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal; at BDSM seminars; major BDSM events; and leather bars. Due to the sensitive nature of the interview content, all interviews were conducted privately either at a university office (Ottawa and Montreal) or at participants’ homes (Toronto).

Data collection for this study consisted of 1) self-administered questionnaires (socio-demographic data, types of preferred sexual practices, frequency of visits to BDSM venues, number of familiar and anonymous partners, perceptions of risk and risk-reduction strategies used within BDSM venues, etc.) and 2) in-depth, digitally-recorded semi-structured interviews.

Standard principles of qualitative research were employed throughout the data analysis (Denzin, 1998). The data consists of completed self-report questionnaires (10) and interview transcripts (10). The research objectives structured the analytical process, and the theoretical framework guided the inductive coding process. An inductive process was followed to ensure the analysis was inclusive and could challenge the current understanding of the phenomenon under study. Diaries and field notes were used to provide additional descriptive information during the analytical process.

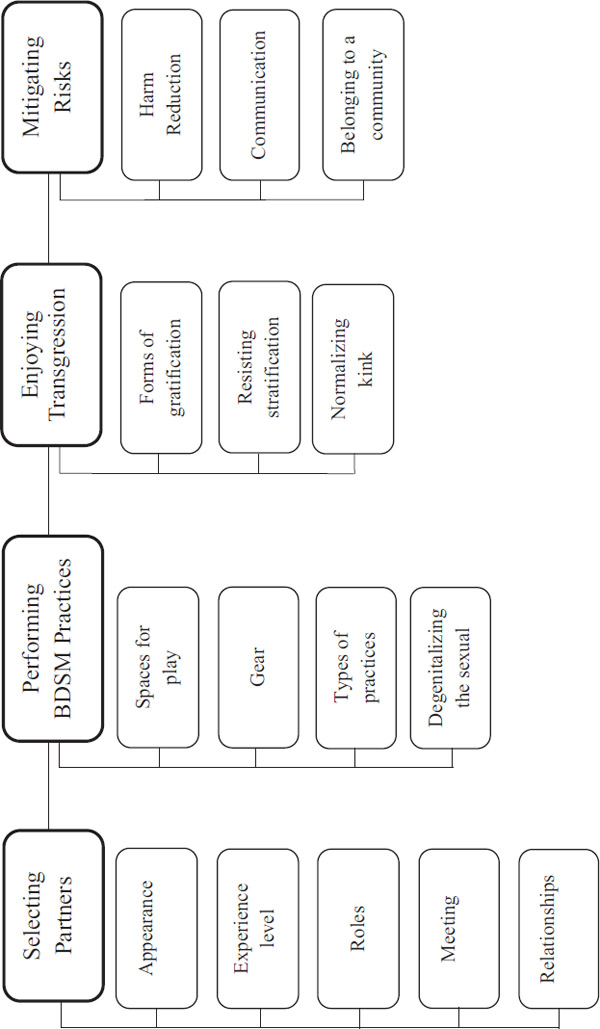

Our qualitative analysis of interview transcripts using the principles of content analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012) rendered four major themes: 1) selecting partners, 2) performing BDSM practices, 3) experiencing transgression, and 4) mitigating risks. Each theme was then subdivided into categories and sub-categories (See Figure 5.1).

The first theme that emerged from the interviews involved factors that participants take into consideration when selecting their BDSM partners, including appearance, experience level, and role preferences, as well as where they meet their partners and the type(s) of relationships they form. Not surprisingly, participants’ responses differed with regards to the physical characteristics that they find most attractive.

We always get dismayed when these videos are done with guys that have had every hair on their body removed … we think that’s a terrible crime.

(TO3, 8)

I have always been very attracted to males that were androgynous and feminine in presentation.

(MTL2, 10)

Participants also considered non-physical attributes when selecting their partners, including their level of BDSM experience. Some participants reported that they prefer their partners to have a similar level of experience.

I’ve been doing so much, so many workshops and demonstrations. Yeah, I’m tired of training. I want to play.

(TO2, 15)

I’m one of those guys who doesn’t like to break-in the newbies when it comes to fisting, because … it takes a lot of time and patience.

(MTL2, 8)

Other participants responded that they actually enjoy playing with novices, because they find that teaching someone about BDSM, and helping them to experience something for the first time, is personally gratifying.

That can be very, very rewarding – to see somebody open up and enjoy themselves that way.

(TO4, 16)

With somebody who’s curious … it’s a great feeling if, you know, when they actually experience something in a play party in the dungeon scene and it’s like, “Wow, this is my first, my first time.”

(TO3, 23)

Another important factor in selecting BDSM partners involves the role that each individual prefers to assume. Participants described a number of different roles, including “dominant,” “submissive,” “sadist,” “masochist,” “top,” and “bottom,” and explained that they frequently seek out partners who prefer roles that are opposite to their own. Dominants, for example, assume control within a relationship and thus generally seek submissive partners, who consensually surrender their control to the dominant. As one submissive explained:

It was always about wanting someone to take it. Like, wanting somebody to take charge of the situation, and control of the situation, and use me.

(TO1, 36)

Sadists, who derive pleasure from inflicting pain on their partner, often gravitate toward masochists, who obtain pleasure from receiving this pain. However, as one sadist described, this interaction must be consensual in order for it to be sexually arousing:

I’m just giving them pain knowing they want pain, and it gets me off that they’re hurting, but they have to be enjoying it.

(MTL2, 2)

Top and bottom are more general terms that are typically used to describe each player’s position within a particular scene, but which do not inherently depict the person’s specific interests or skill set.

There’s a lot of people who call themselves Master or call themselves Dom, only because they’re the top, and they don’t have the skills.

(TO2, 27)

Many participants also referred to themselves as a “switch,” meaning that they are versatile in the roles they take on during BDSM play. This not only increases their number of potential partners, it also allows them to experience the gratification associated with both roles.

I’m a switch. I’m versatile. Mostly a top but … I also bottom. So I like the best of both worlds.

(TO3, 1)

I’m versatile, we’re both versatile. Makes it an easier couple.

(TO5, 3)

Versatile participants provided multiple reasons why they may take on a different role in a particular situation, including their mood and the partner they are playing with.

You may be a top but you had a hard day at work and you come home and it’s, ‘Oh, just do me’, right? So you’re, in effect, bottoming.

(TO4, 12–13)

When do I bottom? … When there’s somebody who actually wants to top me.

(TO3, 1)

Participants reported using different methods of seeking out potential BDSM partners. Some participants felt comfortable engaging in BDSM with strangers they met on the Internet, whereas others preferred to meet new partners in-person.

We’re actually pretty casual in terms of exploring online.

(TO5, 2)

I don’t cruise around on the Net looking for sex. Doesn’t appeal to me.

(TO3, 23)

Regardless of how they met their partner(s), many participants preferred to establish relationships with people they could regularly engage in BDSM with. This is because they felt that having regular partners not only reduces their level of risk, it also improves their experience due to the increased level of familiarity.

[With regular partners] there’s a safety level and … there’s a disclosure level that both of us feel safer with.

(TO5, 13)

It gets so much better when people know each other, and they know what the other person needs, and what they’re looking for, and what their limits are.

(TO1, 28)

Establishing regular partners is also beneficial because some BDSM practices, such as bondage and percussion play, are inherently risky in nature and thus require a substantial level of trust between partners.

Trust is a very big issue … it’s about control, giving up control. Trust is so easily broken, so building it up is an interesting, interesting thing.

(TO4, 29)

It takes a very long time to get the kind of trust that then allows me to enjoy the kind of violence that … my Master likes.

(TO1, 28–29)

Participants reported a number of different types of relationships that can exist between BDSM partners, due to the large range of possible practices and levels of commitment that may be involved. As one participant explained:

There’s the emotional attraction, there’s the sexual attraction, and there’s the kinky BDSM attraction. And you can mix them in any quantities, at any time.

(TO4, 12)

One of the interesting things about BDSM practitioners is their increased openness to non-monogamous relationships, and the lack of jealousy or insecurity that they appear to feel in response. Many participants reported being in an open relationship, which permits them to engage in BDSM and/or sexual activities with people other than their primary partner. In some cases, this is because their partner did not share their interest in BDSM or other specific sexual activities.

I was more of a receptive fisting bottom… . My husband tried but he wasn’t really into it, so I was going to other people to have that need met.

(MTL2, 5)

Other participants explained that they are in a committed relationship, but that they and their partner engage in BDSM and/or sexual activities with other people, at the same time.

We will invite other men as well, into our house, into our bed, to play with.

(TO5, 1)

We both have problems getting into each other [when fisting], but that’s why we have a friend coming over tonight. He’s really good.

(TO3, 1)

The second theme to emerge involved the BDSM practices themselves, including the spaces in which they are performed, the gear that is used, the different types of practices, and the indifference that participants’ often felt toward conventional genital stimulation while engaging in BDSM, which we refer to as “degenitalizing” the sexual. One participant provided an interesting analogy to help explain BDSM:

Think of BDSM as theatre, because it is. You have a stage that’s set, has set decoration on it. You have actors in costumes, they play roles, and the story plays itself out, right? It’s a theatre and the audience is the players.

(TO4, 16)

BDSM practices can be performed in both private and public venues. Some participants prefer playing in private spaces because it allows them to engage in longer play sessions. This is an important advantage because, unlike most regular sexual activity, BDSM often involves extensive foreplay and performance.

Some people will say it’s going to be an evening or an afternoon, other people will say it’s going to be Saturday, or it’s going to be a weekend. With some people, it’s a whole week.

(TO4, 28)

A session … If it’s in a public space, you sort of have to give everyone the chance to play, so it may go 20–30 minutes.

(MTL2, 26)

Unlike public venues, which participants reported are more likely to have specifically appointed dungeon monitors (individuals responsible for ensuring that all players act in a safe, sane, and consensual manner), private venues often use a less formal method, where all players in attendance share this responsibility.

We don’t have any dungeon monitors … there’s enough of us there that if something was going wrong, we would recognize that.

(TO2, 28)

By contrast, participants explained the situations in which a designated dungeon monitor would typically intervene when in a public BDSM venue:

If they’re doing something that is actually unsafe, or … the bottom was in distress and the top wasn’t listening, yeah. Or, somebody was … inebriated to the point where they didn’t really look like they were sober enough to be playing safely.

(TO3, 17)

If people are getting too close in the range of someone who is using percussive devices … or if people are not respecting the space, or are talking too loud or interrupting.

(MTL2, 15)

One benefit of public spaces is that they are more likely to be furnished with BDSM equipment that participants would not otherwise be able to access.

It’s more about lots of furniture … having everything available, lots of different kinds of things… . It’s a little more facilitating, more activity, harder activity.

(MTL2, 13)

Different types of clothing are often incorporated into participants’ BDSM practices, most commonly leather and rubber. While participants varied with regard to which material they preferred, most did have a preference between the two types.

The thing about leather, to me, is that leather and BDSM go hand in hand.

(TO2, 27)

I actually do like rubber more than leather… . You can piss in it. You can get it covered in lube. You can get really messy with it.

(TO1, 35–36)

The two most commonly used accessories were lubricant and gloves, possibly because these items are often involved in the practice of anal fisting, which was by far the most commonly reported practice.

The sensation of being that open and that full is just so incredible.

(TO1, 31)

Once you get used to [fisting], it’s a feeling like, unlike anything else, any other sexual experience.

(TO5, 15)

Other commonly reported BDSM practices include bondage, percussion play, cutting/piercing, electricity play, watersports, and the insertion of urethral sounds. As one participant explained, BDSM scenes often involve a combination of different practices:

I could do flogging beforehand. If someone’s in a sling and I’ve got something inserted in their anus, I can also do oral sex on them. There can be watersports, piss involved, sounds, urethral play, and anal stimulation at the same time.

(TO2, 4)

Interestingly, many participants reported that when engaging in BDSM, they are often indifferent to receiving genital stimulation and/or reaching orgasm, because their primary focus is on the extensive foreplay associated with these practices.

Sometimes the BDSM is even better, but cumming almost becomes secondary in terms of some of the intensity.

(TO5, 16)

More often than not, it doesn’t involve me cumming.

(TO1, 6)

Degenitalizing the sexual is especially prominent with the practice of fisting because, as participants explained, the sensations they receive from fisting are even more pleasurable than reaching orgasm.

Most of the time you’re fisting guys, they’re not erect really … and nobody cares. Like, it’s really not about the penis at that point; it’s really what’s happening with their ass.

(TO1, 32)

The feeling is so different than normal genital manipulation, they’re not really interested in cumming.

(MTL2, 20)

The third theme to emerge involved the transgressive aspects of BDSM, including physical and psychological gratification, a firm resistance to social stratification, and a push to “normalize” kink. With regard to physical gratification, participants were found to derive pleasure from engaging in practices that produce a variety of extreme sensations.

With electricity, you can do crazy things. You can control a current, so it can almost feel like the electricity is fucking you.

(TO1, 35)

Someone’s attached a variable speed sander that he’s adapted to your cock and balls, and meanwhile he’s put a milker on me and so he’s milking me at the same time.

(TO4, 4)

Some participants also reported receiving physical gratification from BDSM practices in which some form of physical pain is inflicted upon them. However, in this context, the pain is experienced as being pleasurable. As one participant described:

I think you’re conditioned, rightfully so, to react to pain and intense sensation by pushing away … it takes experience to not push away, but actually embrace it … and once you do that it’s, it’s incredible. It’s pleasurable.

(TO1, 34–35)

Participants described the importance of understanding that there are many types of pain, which are experienced differently by different people. Consequently, a type of pain that is extremely pleasurable for one person can be quite unpleasant for someone else.

The question is, is it the right amount of hurt? So flogging, for example, I’m not into sting but I don’t mind thud at all.

(TO4, 2)

If [a needle] goes deep into the muscle … it’s a hard thumping pain, and if it’s too shallow, it’s a stinging kind of pain, so it depends on what you want to achieve.

(TO2, 13)

Participants also reported deriving multiple forms of psychological gratification from engaging in BDSM practices. As one participant described, the psychological aspects are often an essential component of BDSM:

It’s not all leather, it’s not all kink … everything starts in the mind … usually goes through the body, and then comes back to the mind.

(TO4, 13)

While some participants took great psychological pleasure in giving up their power and control in order to voluntarily submit to a dominant partner, others derived this pleasure from experiencing humiliation/degradation at the hands of their partner.

There’s no greater moment than when I’m completely in that space of submission … it’s not really sexual, it’s much more profound than sexual. It’s emotional … it’s just joy, it’s just happiness.

(TO1, 17)

To degrade – to make somebody smaller – and a lot of people like that … so you force them to wear something that they would be embarrassed to wear in public and that’s actually a turn on for them.

(TO4, 14)

Participants were divided with regard to whether they consider BDSM practices to be sexual or non-sexual, suggesting that there is no universally correct answer to this question, since it depends both on what the practice is, and how it is interpreted by the individual.

Whether it’s flogging or any other kind of BDSM play, for me it’s all sexual and it’s all intimate … and that’s what I enjoy about it.

(TO3, 8)

Your [questionnaire] talks about BDSM in the context of being a sexual activity, and for a lot of people BDSM is strictly non-sexual.

(MTL2, 3)

Additionally, it was pointed out that the same practice can be both sexual and non-sexual, depending on how it’s performed and the context in which it takes place.

I’m thinking, “Well, is fisting really a BDSM activity? Or is it a sexual activity?” And it depends on how you do it.

(TO3, 8)

Rope could be non-sexual, it could just be for art, like aesthetic purposes, or it can be sensual, or it can actually involve sexual as well.

(MTL2, 1)

It appeared that one of the reasons participants derive such great pleasure from engaging in BDSM is because many of these practices are unconventional and push the boundaries of social acceptability.

When I got into BDSM and then I looked back at my sexual life, I realized that it was always about that… . It was always about transgression.

(TO1, 36)

I remember the first time I put a needle in somebody … it’s entering a person in a way that you’re not supposed to, and it’s for sexual gratification, and it was just exciting, just exhilarating,

(TO2, 13)

Participants also explained that engaging in BDSM practices and being part of a BDSM community allows them to accept and embrace their kinks and desires, which many people in the general public have difficulty doing.

It’s the indulging that a lot of people refuse to give themselves, right? They won’t let go and just indulge their kink, their fantasies, their sexuality. It’s all sort of guilt, religious guilt, or parental guilt… . And it’s part of a process, I think, getting over that.

(TO4, 15)

The final theme to emerge involved the risks and risk-mitigation strategies associated with BDSM practices, including methods of harm reduction, the importance of communication between partners, and the benefits of belonging to a BDSM community.

Participants explained that it’s very important for BDSM players to remain cognizant of the fact that all practices involve some level of risk, and that nothing is guaranteed to be safe, regardless of the precautions that are put in place.

You have to accept that accidents will happen occasionally. Mostly they’re going to be tiny little things but, you know … football players get concussions.

(TO4, 23)

I make sure that they know that there’s absolutely nothing that’s 100% safe, right? Even fucking is not 100% safe.

(TO2, 17)

Since BDSM practices involve different levels of risk, it is essential to know how to properly perform a practice before engaging in it, especially if there is the potential for injury. Percussion play and piercing are two practices that participants felt require specific knowledge in order to perform safely.

When I’m flogging … I don’t hit the back, where the kidneys are … I tend to put a towel around the neck just in case … my aim is a little bit off.

(TO3, 15–16)

Mostly though, if it’s general piercing, it’s always scrotum, and rarely into the testicle because that … can cause a huge infection.

(TO2, 14)

He always uses alcohol swabs on my skin to start … the needles are fresh … we use them once, and he discards them so they’re never used again.

(TO1, 9)

Participants pointed out that it is also important to know how to properly prepare for different practices. With fisting, for example, preparations are different depending on whether the person is a top or bottom. Tops have to focus on trimming/filing their nails and checking their hands for abrasions.

Make sure the nails are trimmed and filed beforehand and no hangnails … and wear gloves. Part of that for me is just a hygiene thing.

(TO3, 6)

Nails are cut short and filed, and certainly I won’t fist with bare hands if I have any abrasions or cuts.

(TO5, 4)

In contrast, bottoms are typically expected to clean out as much fecal matter from their intestinal system as possible. This process is more difficult for some people than others, and can sometimes take up to 12 hours to complete. As one participant explained:

If you’re going to do any major fisting, you at least want your vertical and preferably the transverse colon empty… . It’s not hugely difficult to do, but for some people it’s one technique, for other people it’s another technique.

(TO4, 10–11)

Most participants are acutely aware that some of their practices have the potential to increase their risk of contracting HIV. Consequently, they described a number of strategies they used to mitigate this risk, including the use of gloves and condoms.

When we weren’t playing with anyone else and we were both tested and cleared for many years, it was basically condom-free … but obviously when I am playing with other people, it’s not going to happen.

(MTL2, 4)

All three of us are negative, so. But, as I say, anything that involves penetration we use gloves and condoms with our friend.

(TO3, 5)

Another form of risk aversion that was reported is the use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), a medication that prevents HIV-negative people from becoming infected. One participant described the multiple benefits of taking this medication:

If you follow the stuff around PrEP, I mean a lot of gay guys are finding that it’s as much of a mental health intervention, and that’s very true for me. I’ve always had a lot of anxiety about HIV. I’ve been hyper careful, and it’s been very stressful in my life.

(TO1, 19)

One of the most important, and perhaps simplest, forms of risk aversion is communication between partners, which often takes place before, during, and after engaging in BDSM practices. Participants reported that, before engaging in BDSM, it is essential to disclose their own HIV status and know the status of all players involved.

If I’m playing casually with someone, I’ll have a little chat before with them and tell them that, “I’m clean. I test regularly. What is your status?” And if they can’t tell me their status … then I’m not really interested.

(MTL2, 22)

Participants explained that, prior to beginning a scene, players need to discuss and negotiate the details of the scene, not only to determine each player’s interests, but also to establish soft and hard limits, and to ensure that everyone is freely consenting.

You just ask, “Is it the clothes, the fetishistic clothing? Is it bondage? Is it percussion play? Are you into needles? Humiliation?” Usually when we mention one, the eyes will light up one way or the other.

(TO4, 17)

We talked for a couple weeks as to what he would like and what I would like to do, and we determined what would be allowed.

(TO2, 15)

During a BDSM scene, the most important form of communication for mitigating risk is the use of a safe word, which is a word or phrase used to indicate that the scene needs to be modified or stopped altogether. As one participant explained:

Some people like to just use a word, like cabbage or uncle or whatever. Some people like stoplights – green, red, and yellow. So … you can come in and say, “How are you?” And they’ll say, “Yellow.” And then, “Okay … what would make it go red or what would make it go green?”

(TO4, 19)

When engaging in BDSM practices that involve restraining the bottom and/or restricting his ability to speak, participants may use a safe motion rather than a safe word.

If they’ve got a gag or a mask on … and even if they’re tied down, I make sure that their one hand has some motion or else I give them something to hold, and they can move their hand or drop it.

(TO2, 12)

While most participants felt that the use of safe words/motions is important for novice players, they also reported that very experienced players will often rely more on body language to determine when to modify or end a scene.

As you get more experienced, you get to a point where you can read each other’s body language, their facial expressions. And the top, generally speaking, won’t need a safe word.

(TO4, 21)

He’s taken a very, very long time to get to know me … I think he can tell by my vocalizations when things are getting to the point where I’m having difficulty taking it.

(TO1, 15)

Some participants felt that it is important to communicate with their BDSM partner(s) the day after a scene, either to ensure that no injuries had resulted from the play or to discuss how the scene went in order to learn from the experience.

Needles and cutting, for example, even if I’ve met them online … I tell them that I want them to contact me the next day to let me know how things are.

(TO2, 17)

I’m required to report within about 24 hours about the experience I had with him… . I think that’s been his way of … learning about my limits, learning about who I am, what motivates me… . And that informs his use of me.

(TO1, 4)

Belonging to a BDSM community is another method of risk mitigation, as the community not only provides formal and informal education, it also identifies and expels dangerous players. Formal education involves workshops, demonstrations, and seminars, designed to teach people how to safely perform different BDSM practices.

We did a piercing demo … everyone was given a hypodermic and they were told, “Okay, this is how you clean your skin and, you know, just put the needle into your skin and have it come out the other side.”

(TO4, 5)

Having a booth at the fetish fair … we’d have sets of sounds there that we would sell and other toys and things and people said, “So, have you used this?” And you talk to them about it, how it’s done, and give them some tips.

(TO3, 22)

Belonging to a community also provides informal education, which primarily involves learning about BDSM by engaging in different practices with experienced players.

[I] found people who were really good at what they did and who were highly recommended, and I only played with them until I knew what was going on.

(MTL2, 8)

Finally, being part of a BDSM community helps participants meet new partners who they feel safe engaging in BDSM practices with, because these individuals have been vetted by the community and determined to be safe, sane, and consensual players.

Could be like sixty people there over the course of the night, but at least you kind of know who they are … that they’re nice guys, and they’re good players, and they’re responsible, and they know what they’re doing.

(TO3, 23)

Occasionally I would meet someone who’d want to play, but it was always in the context of people who weren’t new to the scene and could tell me like, “Yeah, don’t play with that guy.”

(MTL2, 17)

Our results above provide a snapshot of BDSM practices in the MSM communities under study, as well as ethnographic insights into the sexual culture of these communities, particularly as they are germane to health care and public policy. This is only a beginning, to bring to light some BDSM desires and practices in order to better understand – rather than to police – those communities served by public health professionals. In more general terms, our results extend beyond BDSM subcultures, providing insights into other “unconventional” sexual subcultures and even mainstream “vanilla” sexualities, demonstrating how the pursuit of sexual pleasure is a socio-cultural and symbolic practice that also happens to be biological, but which may or may not involve genital penetration or even genital stimulation. Admitting the diverse and deeply cultural dimensions of sexual pleasure will undoubtedly frustrate attempts to derive from these data prescriptive public health interventions, quantitative strategies, norms, or “actionable outcomes” in the design and implementation of more effective measures for the prevention of HIV and other STIs. This has not been our express intent. Rather, our qualitative research suggests the need for culturally competent public health care and support services – both physiological and psychological – without normalizing judgments or moral orthopedics. These findings thus rattle the more traditional binaries associated with public health: as agents of the state, health care providers are not simply subject to the paradoxical responsibilities of advocating “safer sex” through dominant public health messaging, on the one hand, and respecting a patient’s individual desires and practices, on the other. In other words, when we begin to understand the socio-cultural and symbolic dimensions of sexual pleasure, there is no longer a strict dichotomy between autonomy and community, between individual and population. These relations are, from the start, forged in and through communities; public health is never simply about the biological regulation of bodies-at-risk. This calls for a radically different approach to public health ethics, which is beyond the scope of our study (see Guta et al., 2016).

From an ethical perspective, however, it is nevertheless significant to note the divergent ways that the operative notion of “community” is constituted – by institutionalized public health discourse, on the one hand, and by the BDSM community itself, on the other. We might say there is a clash of cultures here, which relates to the divergent ways that power is deployed and taken up. The governmental power allied with public health discourse is, in Foucault’s (1989) words, “a strategic relation that has been stabilized through institutions” (p. 387). With respect to public health, then, “the mobility of power relations is limited, and there are strongholds that are very, very difficult to suppress because they have been institutionalized” (p. 387). In contradistinction, for Foucault (1989), BDSM practices stand in stark contrast to the “institutionalized” and “rigid” stratification of power relations enacted by social apparatuses such as public health:

S/M is the eroticization of power, the eroticization of strategic relations … [It] is a strategic relation, but it is always fluid… . I wouldn’t say that it is a reproduction, inside the erotic relationship, of the structures of power. It is an acting out of power structures by a strategic game that is able to give sexual pleasure or bodily pleasure.

(pp. 388–389)

The strategic game of BDSM is more fluid in its negotiation and experience of power relations. Our results above tend to confirm Foucault’s insight: those who practice BDSM form a subculture rather than a counter-culture because their practices do not simply or purposefully defy the regulatory power relations that are instituted by public health authorities; rather, these relations are eroticized and incorporated in the game. Defiance or resistance are useful concepts here, but these terms must be nuanced.

Critical public health scholarship typically characterizes public health prevention strategies as a form of governmentality (Foucault, 1991; Lupton, 1999), where subjects are imagined to resist the “authoritative nature of the state and its incursions into their private lives” (Lupton, 1999, p. 134). And it is no doubt true that when the imperatives of external governing agencies collide with an individual’s desires or self-image, a sense of dissonance or uneasiness can occur, and this may indeed lead to individual resistance (Burchell, 1991). This is especially true in the case of already marginalized populations. Each individual, though penetrated and constructed by power relations, is positioned at the intersection of external forces (discourses) and hence constitutes “a point of potential resistance” (Rose & Miller, 1992, p. 190). Public health workers are accustomed to such points of resistance. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1980), the “sexual” body is a site where “libidinal forces” are struggling against external social forces, suggesting that social norms (that are part of governing strategies) attempt to exercise their power by marking (mapping) and shaping bodies. For instance, at the very moment that public health imperatives are marking the body, compelling it to obey, that selfsame body is simultaneously fed by desires, which continuously disrupt the protocol of the “body map makers” (e.g., public health authorities) (Patton, 2000). The tensions between a territorializing system (epitomized in the health care system, the government, and other such institutions) and rebellious individuals is implicit in studies of bareback sexual practices (Hammond, Holmes, & Mercier, 2016; Holmes & Warner, 2005; Holmes & O’Byrne, 2006; Holmes, Gastaldo, & O’Byrne, 2007). But it would be a mistake simply to extend these analyses to the BDSM community, whose sexual practices are in many ways disanalogous to barebacking.

Our study demonstrates that BDSM practitioners do not defy the safer sex messaging conveyed by public health authorities. Participants are highly conscious of the risks associated with HIV and STIs, particularly in the context of their specific practices – practices that may otherwise pose a risk (e.g., “bloodsports”) but that are predominantly non-sexual, which is to say, BDSM practices do not necessarily involve genital penetration and the exchange of semen, practices conventionally associated with the transmission of HIV. Moreover, participants engage in robust and sustained communication to ensure the physiological and psychological safety of their partners. Ethical protocols for informed consent are part of their erotic play. And they understand that their risks are for the most part associated with their choice of partner and with non-genital play, which may involve open wounds, feces, and the like. Given the precautions taken, the risk of contamination from HIV is low, if not absent.

It is perhaps more correct to say that BDSM practitioners do not defy or simply resist the safer sex message of public health authorities, they creatively resist dominant public health protocols – the manner and means by which that message is conveyed and compliance is sought. They have integrated their own procedures for safer sex, as part of their sexual practice; if their sexual practices might be considered transgressive, safer sex practices as such are not typically transgressed, and safer sex procedures are based on the risks associated with particular activities, of which participants are mindful. A poststructuralist analysis of power relations at the individual and collective level (Federman & Holmes, 2000; Gastaldo, 1997; Holmes, 2002; Holmes & Federman, 2003a, 2003b; Petersen & Lupton, 1996) might therefore help expand public health discussions to include marginalized and minority populations, such as BDSM practitioners. Such an approach would be sensitive to the dominant discourses (e.g., public health) and competing discourses (pleasure/desire and risky sex) surrounding this subculture (Foucault, 1994). Here, a queer theory perspective might also prove invaluable. Emerging from a gay and lesbian “rework” of poststructuralist research, where subjectivities are theorized as being fluid, multiple, fractured, discontinuous, and unstable (Butler, 1990, 1993, 2004; Foucault, 1994), queer theorists argue for the impossibility of any “natural” sexuality or sexual hierarchy, and thus suggest an alternative way to conceptualize the “sexual.” Importantly, queer theory reveals how gender operates as a regulatory construct, and how the deconstruction of normative models of sexual practices can legitimate some socio-political agendas. Consequently, queer theorists have made significant contributions to the understanding of BDSM sexual practices and desires (Jagose, 1996). And it is from such a discussion that we might begin to envisage culturally competent public health interventions that understand and address the context-specific needs of minority populations and subcultures, and that avoid a “one size fits all” approach. Indeed, health care professionals might look to BDSM cultures, not so much in order to tailor the message they convey, but as an occasion for a critical ethnography of their own culture – the culture of public health – and from this auto-critique, to think anew the message of risk reduction, strategic intervention, and ethical practice.

Burchell, C. (1991). Introduction. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon, & P. Miller (Eds.). The Foucault Effect (pp. 1–51). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. New York: Routledge.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1980). Mille Plateaux: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie 2. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

Denzin, N. (1998). The art and politics of interpretation. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds). The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues (pp. 500–515). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Federman, C. & Holmes, D. (2000). Caring to death: Health care professionals and capital punishment. Punishment and Society, 2, 439–449.

Foucault, M. (1994). Histoire de la Sexualité: La volonté de Savoir. St-Amand: Éditions Tel/Gallimard.

Foucault, M. (1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon, & P. Miller (Eds.). The Foucault Effect (pp. 87–104). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, M. (1989). Sex, power and the politics of identity. In S. Lotringer (Ed.). Foucault Live (Interviews, 1961–1984) (pp. 382–390). New York: Semiotext(e).

Francis, B. (2000). Poststructuralism and nursing: Uncomfortable bedfellows? Nursing Inquiry, 7, 20–28.

Gastaldo, D. (1997). Is health education good for you? Re-thinking health education through the concept of bio-power. In A. Petersen & R. Bunton (Eds.). Foucault Health and Medicine (pp. 113–133). London: Routledge.

Grbich, C. (1999). Qualitative Research in Health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Guta, A., Murray, S.J., Strike, C., Flicker, S., Upshur, R., & Myers, T. (2016). Governing well in community-based research: Lessons from Canada’s HIV research sector on ethics, publics and care of the self. Public Health Ethics, 1–14.

Hammond, C., Holmes, D., & Mercier, M. (2016). Breeding new forms of life: A critical reflection on extreme variances of bareback sex. Nursing Inquiry, 23(3), 267–277.

Holmes, D. (2002). Police and pastoral power: Governmentality and correctional forensic psychiatric nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 9, 84–92.

Holmes, D. & Federman, C. (2003a). Constructing monsters: Correctional discourse and nursing practice. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 8, 942–962.

Holmes, D. & Federman, C. (2003b). Killing for the state: The darkest side of American nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 10, 2–10.

Holmes, D. & O’Byrne, P. (2006). The art of public health nursing: Using confession technè in the sexual health domain. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(4), 430–437.

Holmes, D., O’Byrne, P., & Gastaldo, D. (2007). Setting the space for sex: Architecture, desire and health issues in gay bathhouses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 273–284.

Holmes, D., O’Byrne, P., & Murray, S.J. (2010). Faceless sex: Glory holes and sexual assemblages. Nursing Philosophy, 11, 250–259.

Holmes, D. & Warner, D. (2005). The anatomy of a forbidden desire: Men, penetration, and semen exchange. Nursing Inquiry, 12, 10–20.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer Theory: An Introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Lupton, D. (1999). The Imperative of Heath: Public Health and the Regulated Body. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Newmahr, S. (2008). Becoming a sadomasochist: Integrating self and other in ethnographic analysis. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 37, 619–643.

Ottawa Public Health. (2011). June 2011 Monthly Communicable Disease Report. Retrieved from www.ottawa.ca/calendar/ottawa/citycouncil/obh/2011/0815/Supporting%20Document%20to%20Report%201%20ENG.pdf.

Patton, P. (2000). Deleuze and the Political. New York: Routledge.

Petersen, A. & Lupton, D. (1996). The New Public Health – Health and Self in the Age of Risk. London: SAGE.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012a). At a Glance – HIV and AIDS in Canada: Surveillance Report to December 31st, 2011. Retrieved from www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/survreport/2011/dec/index-eng.php.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012b). Summary: Estimates of HIV Prevalence and Incidence in Canada, 2011. Surveillance and Epidemiology Division, Professional Guidelines and Public Health Practice Division, Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control. Retrieved from www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/index-eng.php#er.

Rofes, E. (1996). Reviving the Tribe. New York: The Haworth Press, Inc.

Rose, N. & Miller, P. (1992). Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. British Journal of Sociology, 42, 173–205.

Sagarin, B.J., Cutler, B., Cutler, N., Lawler-Sagarin, K.A., & Matuszewich, L. (2009). Hormonal changes and couple bonding in consensual sadomasochistic activity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 186–200.

Taylor, G.W. & Ussher, J.M. (2001). Making sense of S&M: A discourse analytic account. Sexualities, 4, 293–314.

UNAIDS. (2010). 2009 Fact sheet: North America and Western and Central Europe. Retrieved from www.unaids.org.

Weinberg, T.S. (2006). Sadomasochism and the social sciences: A review of the sociological and social psychological literature. In P. Kleinplatz & C. Moser (Eds.). Sadomasochism: Powerful Pleasures (pp. 17–40). Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press.