Under the sea, everything was changed. To their surprise, none of the girls felt frightened, my mother told me, but rather “felt just exactly the way things were meant to be, Snow.”

(For this was my favorite story as a child, one I had from my mother, and from Kim, and even from Star.)

There is a lot you see under the sea, my mother told me. Kim, too, told me “there’s ever so much more than you see on land, Soph,” as she tucked me into the huge bed I’d inherited from Lily. “I think it musta been cuz of how dead quiet it is there.” There under the sea, she said, noise is not constantly pushing and pulling at you. You can just move in one direction and see, quite clearly and plainly, where you’re headed.

I’ve never been there myself. But I have imagined.

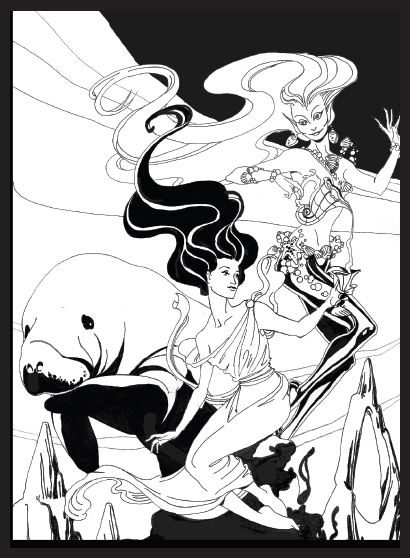

And then, they weren’t alone. (How I loved this part of the Story of Going Under the Sea!) Almost immediately, as the three followed the slope of a hill down under the clear blue water, they attracted a crowd. Now there were three dolphins swimming alongside, their bottlenoses and their silver bellies showing as they twisted and rolled along. There was a wedge-shaped formation of rays complete with teeth and whipping tails. There was a line of green eels. And, overhead, as the girls looked up, there were hundreds, “maybe thousands, Soph, just imagine it! You never saw such a thing,” of tiny, eager fish. They were all the colors of the rainbow, Kim said: “red and white and yellow and purple.”

The girls laughed but they made no sound. They smiled at each other and held hands. And they walked on.

The farther they went, the more company they had, underwater creatures of all kinds: shrimps, and squids, and swimming sponges; sharks and soles, and red and orange snappers; rainbow-colored mackerel, and marlin…

And then…there was a Manatee. Big and bulky and with a strangely ill formed back tail. They only caught a glimpse of him at first. They were so overwhelmed by all the show around them, by the welcome they were getting from the Sea, it was hard to take it all in. Hard to take in any detail past the larger feeling of joy that came on them now.

The more company the girls had, the happier the girls felt. This was a particular feeling that all three recognized as the same that had swept them, together, into the sea. They had not been driven to it, as Livia wanted (which must have frustrated her utterly, if I know my grandmother). They had gone together. None of them could say why they had done so, but I can tell you that they had gone together for love.

And so the company that joined them now joined them for love. They didn’t know it, any more than a fish knows it swims in water. They accepted it as natural, and they just walked on.

The three girls held hands now and walked straight forward, catching sight, from time to time, of the Manatee as it swam shyly along, first behind a dolphin, then beside an anemone. It was as if the huge, clumsy creature wanted them to see him, to notice him in some particular way, but was too bashful to call attention to himself.

Lily gave him a closer look. He had flipper-like hands, which he used in a precise, almost dainty way. His tailfin was almost round, and flat, and propelled him more gracefully through the water than you could imagine, if you looked first at his enormous brown and wrinkled bulk. All the more surprisingly since the tail was lopsided, as if he’d been injured somewhere. If he had been able to walk, he would have limped.

This reminded Lily of something. But she couldn’t quite remember what.

Then there was his face. Lily could see that it was long and silly, but with a kind of noble nose topping the whole. The Manatee was very silly-looking indeed, and wistful, too. Lily pondered this. It seemed to her that she had seen this expression before, that somewhere she had once known someone very like the Manatee. But the moment she thought this, that thought washed away in the water around her and was gone.

As she looked over at the Manatee, trying to puzzle some sort of sense out of him, she saw him duck his head, putting one flipper over his eye and peering out back at her from under it. Then the huge unwieldy creature drew himself up to his full length—he was, indeed, very long; I used to laugh and clap my hands at this point in the story when Kim would describe how long—and swam ponderously forward. He swam beside the girls and then, with a churning of the water, gave a bow that was courteous in the extreme. Lily, observing him close up now, gave a start. The Manatee looked at her intently from his tiny gray-brown eyes. There was something about those eyes that was very familiar indeed. They were silly, and, tiny as they were, they bugged out a little. Lily knew that she had looked into those eyes many times before, and in many places, too.

But how could that be? She puzzled to herself. How could that be so?

The Manatee turned with the girls now, and swam along beside them, his tail flapping comfortably as they went. Lily watched him, but for now he kept his silly muzzle pointing straight ahead. Just for now he didn’t meet her eye.

Down and down they walked, deeper into the sea. Or rather, they didn’t walk down—they walked, no matter how far, as if on even land. It was a long, flat plain the girls walked along with the fish swimming beside, one that stretched out farther than you could see.

It was the sea above them that got deeper and deeper as they walked. Deeper and deeper and deeper, until, when they looked up, they could see nothing but water overhead for miles. And to their further surprise, the farther they went, the lighter the seawater became around them. First it was a shiny blue-green, then turquoise, and then, as they neared their destination (“though how we knew we had a destination, much less that we were near it, none of us could have said,” my mother told me later), a pale gold-blue shimmered all around them, turning any other color it surrounded into a deeper, realer version of itself.

All of this Lily saw. “I could see quite clearly, Snow, there under the Sea.”

The Manatee, as he swam, courteously holding Lily’s arm on one of his oval-shaped, velvety fins, looked more and more to Lily, as they went on, like the most comfortable armchair by the warmest fire you could imagine. His dark gray pelt took on a burnished look, as if reflecting the cheerful flames there. And his eyes, though tiny, shone deeper and brighter, too.

And then there was Kim. She changed too. “Ooooh, I did and all, Soph. I were never the same again, no never.” Her blonde hair turned golden as they went on in that blue-gold light. Here and there it escaped the black plastic clasp she used to hold it back, and floated in tendrils around her face. The fish, swimming with them, teased her by nipping at the floating ends. “Oooh, they made me smile, them fish!” But she never said a word.

As for quiet Phoebe, her face changed, too—it became whiter and whiter as they went on, until it glowed like the Moon Itself, and the more her skin glowed, the quieter she became. The quieter she became, the more her smile shone like a sharp silver crescent on her face. And Lily, seeing this, realized that, since they’d come together under the sea, her silver-haired friend hadn’t said a single word.

It was only then, when Lily marveled to herself at this, that she realized that she, too, was silent. She opened her mouth, experimentally, just to say one word, and she found, not that she couldn’t, but that she wouldn’t. Although why she wouldn’t she could not have said. And Lily, as she walked along the golden sand that showed their footprints for only an instant before the sea washed them away, pondered this.

Without knowing it, Lily and the others had passed through the Sea Change that happens along the long walk to the Mermaids’ Deep—for it was to that very place, known to all the girls from the stories of their earliest childhoods (known to all of us from all of ours, as well), that they walked now. After this, none of them would be the same. Each changed in her own way, which, of course, is the way it is with change.

THE MERMAIDS’ DEEP