Chapter 8: Solar Hot Air

Another option for clean, affordable heat is a solar hot air system. Solar hot air systems capture sunlight energy striking a collector mounted on or near a building. The solar hot air collector heats indoor air that is circulated through the collector, then sends it back into the building. These systems can provide years of inexpensive, worry-free comfort.

Solar hot air systems are primarily installed on houses, but they can also be used to heat office buildings, workshops, garages, and barns. Very large systems can be installed on warehouses, factories, and other big commercial buildings.

Like other renewable energy technologies, solar hot air systems free homeowners from worries over rising fuel costs. Solar energy costs the same today as it did when humans first appeared on the savannahs of Africa — nothing. In this chapter, you will learn how solar hot air systems work, how they are installed, and what the costs and return on your investment might be.

How Do they Work?

Solar hot air systems are fairly simple devices, far simpler and easier to install than passive solar or solar hot water space-heating systems, the topic of Chapter 9. They’re also a lot cheaper, and do not require complicated electronic controls. If you’re skilled, you can even build a solar hot air system yourself (Figure 8-1).

Fig. 8-1: It’s not that difficult to build a solar hot air collector. (a) This solar hot air panel designed and built by Missouri resident Mike Haney shows what’s possible with a little time and a lot of skill. (b) This fairly crude but effective system is used to heat a house in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Solar hot air systems produce heat earlier and later in the day than solar hot water systems. As a result, “they may produce more usable energy over a heating season than a liquid system of the same size,” according to the DOE’s online publication, “Consumer Guide to Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.” Moreover, air systems do not freeze. Minor leaks in the collector or distribution ducts that can cause significant problems in hot water systems are of lesser consequence in hot air systems. So what does a solar hot air system look like?

All solar hot air systems rely on a collector (described shortly). The collector is typically mounted on the roof of a house, but may also be mounted on vertical south-facing walls or even on the ground (if it’s not shaded during the heating season). As you shall soon see, vertical south-facing walls are the best location.

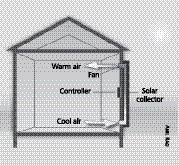

Solar hot air collectors capture sunlight energy and use that energy to heat room air that circulates through them (Figure 8-2). The solar-heated air is transferred into the interior of the building, thanks to a small AC or DC fan or blower.

Fig. 8-2: This diagram shows how air is circulated through and heated in a solar hot air collector.

Solar hot air systems are controlled by relatively simple electronics (unlike solar hot water systems). A temperature sensor mounted inside the panel monitors collector temperature. When it climbs to 110° F, the sensor sends a signal to a thermostat inside the home. It, in turn, sends a signal to the fan or blower, turning it on when room temperature drops below a desired temperature setting. When the temperature inside the collector drops to 90° F, the fan switches off.

Solar hot air systems provide daytime heat on cold, sunny days (unlike solar hot water systems, which are designed for daytime and nighttime heat thanks to their ability to store heat in water tanks). Some early systems stored hot air in rock storage bins for use at night or during cloudy periods. Although ingenious, this approach generally proved to be disappointing —quite disappointing. Designers found it difficult to achieve adequate and predictable airflow through rock beds. Rock storage also poses a health risk. As green building expert Alex Wilson notes, rock beds “can become an incubator for mold and other biological contaminants — causing indoor air quality problems in the home.” Because of these problems, most rock bed storage systems have been abandoned.

Even though solar hot air systems used today principally provide daytime heat, the heat they produce can accumulate indoors during the day. For example, it may be absorbed by drywall, tile, or the framing lumber of a building. In the early evening, the heat stored in these forms of thermal mass radiates into the rooms, helping create evening comfort. Obviously, the more thermal mass, the greater the nighttime benefit. Even so, solar hot air systems are still primarily considered daytime heat sources.

Types of Solar Hot Air Collectors

Although you may not have heard about solar hot air systems, they’re not a new technology by any means. They’ve been around since the 1950s. Today’s systems fall into two categories: open- and closed-loop.

Open-Loop Solar Hot Air Collectors

The newest solar hot air system is the open-loop design (Figure 8-3). Hot air collectors in open-loop systems extract cold air not from the building, but from the out-of-doors. They heat this air, and then transfer the heated air into the building. Collectors used in open-loop systems are known as transpired air collectors.

Fig. 8-3: In this design, cold outside air is drawn into the collector where it is heated. The warmed air is then blown into the building. These systems are primarily used in large warehouses, which are not very airtight and need only a modest amount of heat.

A transpired air collector consists of a dark-colored, perforated metal facing, known as the absorber plate (Figure 8-4). The sides and back of the solar hot air collector are made from metal and are typically insulated to reduce heat loss.

Fig. 8-4: Absorber Plate of Solar Hot Air Collector.

Sunlight striking the absorber plate of a transpired collector heats the surface. Heated air is drawn into the collector by a blower and is then piped to the interior of the building.

Closed-Loop Solar Hot Air Collectors

A closed-loop solar hot air system, the most popular and effective option, consists of a glazed flat-plate collector (Figure 8-5). Inside the collector is an absorber plate. (The absorber plate has a rough surface that increases turbulence inside the device. Turbulence helps strip heat from the absorber plate). The collector is insulated and covered with single- or double-pane glass (glazing).

Fig. 8-5: This collector from Your Solar Home is mounted on my garage. It contains its own source of electricity, a small solar panel that powers the fan that moves air through the collector.

In closed-loop systems, cool air is drawn into the collector from the interior of the building and then heated as it passes through the collector. The heated air is then blown into the building. Room air is typically drawn into the panel through a short section of pipe that runs through the wall or the roof of a building, although longer duct runs are used in some applications.

Air entering the intake duct passes through the collector, either behind the dark-colored metal collector surface (back-pass collectors) or in front of it (front-pass collectors). Back-pass models come with single-pane glass; front-pass models require two-pane glass to reduce heat loss. Heated air is blown into the building through a pipe or duct (kept as short as possible). Small registers are mounted on the air intake and outtake openings that penetrate the exterior walls of the building.

Of the two types of glazed solar hot air collectors, back-pass collectors are most common. They’re cheaper to manufacture and about 50 pounds lighter than front-pass collectors and, therefore, are a little easier to install.

Like transpired air collectors, glazed collectors in closed-loop systems are thermostatically controlled. Both closed-loop and open-loop systems employ backdraft dampers to prevent air from flowing in reverse at night via convection, a natural phenomenon that will suck heat out of a building.

Installing a Solar Hot Air System

Installing a solar hot air collector is not a job for novices. Although, as solar expert Chuck Marken notes in his article on solar hot air systems in Home Power magazine, “a seasoned crew of two can install a solar hot air system in a few hours…[but] if this is your first time, plan on a weekend, even with help.”

Mounting Options

As noted previously, the best place to mount a solar hot air collector is on the south side of a house, provided it is unshaded during the heating season. Mounting the collector vertically on a south-facing wall ensures maximum solar gain during the coldest months — when you need the heat the most (Figure 8-6). (Vertical mounting means the collector is more closely aligned to the incoming solar radiation from the low-angled winter sun.) Mounting on a south-facing wall also shades the solar hot air collector during the summer from the high-angled summer sun, especially if the building has adequate overhang.

Fig. 8-6: Mounting a solar hot air collector on the south side of a building is ideal.

The second most desirable location for a solar hot air collector (though infrequently chosen, according to Todd Kirkpatrick of Your Solar Home) is on a rack mounted on the ground. This is known as a ground-mounted solar hot air collector. The rack must be anchored to a suitable concrete foundation, for example, concrete piers.

Ground-mounted systems require considerable ductwork — as do roof-mounted systems, discussed shortly. Due to the large amount of ductwork, both systems require sizable fans to ensure adequate airflow.

Because they function primarily during the heating season — when the Sun is low in the sky — solar hot air collectors should be mounted more vertically than solar electric modules, which are mounted to absorb as much sunlight as possible through the whole year. The tilt angle of the solar hot air collector, that is, the angle between the back of the module and a line running horizontally from the bottom of the collector, should be set at latitude plus 15°. If you live at 45° north latitude, for instance, you should mount a collector at 60°. If you live at 35° north latitude, the tilt angle should be 50°.

One of the most popular of all places to mount a solar hot air collector, though one of the most problematic, is on the roof. Roofs are popular because they often are unshaded during the heating season. And because roofs often tower above other buildings — and even mature trees in some cases — they provide good access to the winter sun in densely populated urban and suburban environments.

Unfortunately, roof mounts can be more complicated and more costly than wall or ground mounts. In homes with attics, for instance, installation requires the use of flexible insulated ducts to transport air to and from the collector. Unfortunately, flexible insulated ducts are ribbed, which greatly increases air turbulence, which reduces airflow. Partially because of this problem, much larger fans are required in roof-mounted systems. In homes with closed ceiling cavities, collectors require much shorter duct runs however. The same goes for wall-mounted collectors.

Another problem with roof mounts is that they are exposed to sunlight year round, while most of us need heat only during the late fall, winter, and early spring. Intense sunlight during the summer can, over the years, damage a roof-mounted solar hot air collector, so professionals generally recommend against such installations. However, if that’s the only location you have, you can still install one, but cover the collector during the summer.

Pointers for Mounting a Collector

Precise directions for installing a solar hot air collector are beyond the scope of this book, however, a few comments and suggestions are in order — so you know what you are getting into.

To install a glazed solar hot air collector, you’ll need to cut two large (five to seven inch) holes in the wall or roof and ceiling. When cutting holes in a wall or roof, be certain not to damage water pipes or cut or damage electrical wires. Work slowly, checking for potential obstructions. Cut a hole in the drywall or siding, then check for wires and pipes. Manufacturers provide metal mounts to attach to the exterior wall (or roof). The solar hot air collectors are attached to these mounts.

Because collectors are heavy and large, measuring around four by seven feet, you’ll need a couple of brawny assistants to make sure the job goes right and to protect your back and toes. (You don’t want to drop one of these collectors on your foot!)

When installing a collector, you’ll also need to do some wiring, for example, you’ll need to run electric wire to energize the fan or blower. You will also need to wire the thermostat (it comes with the unit) to the temperature sensor mounted in the collector. Wiring diagrams can be difficult to understand for the electrically illiterate.

To make your life easier, two manufacturers have provided some rather ingenious and simple wiring alternatives. Canada’s Your Solar Home, for instance, manufactures a solar hot air collector known as the SolarSheat (Figure 8-5). It comes with its own supply of electricity: a small solar electric module mounted above the solar hot air collector. The solar electric module generates direct current (DC) electricity when struck by sunlight. The DC electricity it generates powers SolarSheat’s DC fan. All the installer or homeowner needs to do is to wire the system to two wires that connect the collector to the thermostat inside the house. It’s about as simple as you can get, as I learned when I installed mine.

Another ingenious solution to simplify wiring is provided by Cansolair. Cansolair’s Solar Max is a glazed solar hot air collector made from 240 empty aluminum cans (Figure 8-7).

Fig. 8-7:

Cansolair Solar Hot Air Collector.

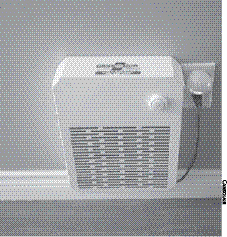

The cans are painted black, arranged in 15 vertical columns, and housed in an attractive collector. Air flows through the solar-heated cans inside the collector. Airflow is supplied by an indoor fan that plugs into a 120-volt wall outlet. It propels room air through the duct system and then through the collector, and back again into the building. The fan, which is housed in an attractive console, also contains a washable filter that helps remove large particles from the air (Figure 8-8).

Fig. 8-8: The Solar Max fan and filter conveniently plug into a wall socket, eliminating complicated wiring.

Although solar hot air collectors are often attached to existing walls or roofs, DeSoto Solar sells collectors that can be integrated into walls, reducing the collector’s profile. Your Solar Home also has collectors that can be integrated in the exterior walls, but these products are best for brand-new construction or additions. It is much easier to install a collector in a wall before the sheathing and siding have been installed.

How Well do They Work?

Solar hot air systems boost the temperature of air flowing through them — often quite substantially. According to the DOE, “Air entering a (glazed) collector at 70° F (21° C) is typically warmed an additional 70–90° (21–32° C).”

Transpired air collectors may provide considerably less heat than glazed collectors. Solar energy expert Chuck Marken notes that transpired air collectors only increase the temperature of the air flowing through them around 11° F (52° C), which is of little value for residential structures, although it can be useful in factories, warehouses, indoor lumber yards, livestock enclosures, and the like, where a little bit of warming can dramatically improve working conditions for employees.

Ralf Seip, a homeowner who installed a SunAire glazed solar hot air collector to heat his basement workshop in Michigan, found that his collectors raised the temperature of the air flowing through them slightly less than 70° F (21° C), but only for an hour and a half to two hours a day during the peak of solar gain on sunny winter days. (That is, when solar irradiance is at its highest.) During the rest of the day, the system elevated temperature, but not as much as during peak sun. His system raised room temperature in his basement workshop by about 3.6° F (2° C) on cloudy days and 11° F (6° C) on sunny days. Although daytime temperatures in the workshop only reached 63° F (17° C), that was suitable for working.

Individuals who’ve installed solar hot air systems report impressive results. Steve Andrews, a residential energy expert based in Colorado, for example, installed a collector to heat the bottom 500 square feet of his tri-level home in sunny Denver. This area was usually 5–6° F colder than the rest of the house. He found that the solar hot air collector “made a difference during sunny winter days and the following evenings.” Although the system was of little or no help on very cloudy or snowy days, “overall, the comfort improvement was dramatic.”

The SolarSheat 1500G I tested while researching an article on solar hot air collectors for Mother Earth News (from which this chapter was adapted), consistently raised the temperature of indoor air entering the collector at around 68° F (20° C) by 40° F (4.4° C) on sunny cold winter days. It didn’t make much difference in the room temperature, but I was dumping the heat into a very large open space of over 2,400 square feet. I’m certain the collector would have made a substantial contribution in a smaller room. This leads us to an important question: How much space can a solar hot air collector heat?

Solar expert Chuck Marken recommends one 4 x 8 foot collector per 500 to 1,000 square feet of heated space, depending on the solar resources at one’s location and the energy efficiency of the building. A 2,000-square-foot home, for instance, would require two to four collectors. Separate collectors may be required for each room. For larger rooms, it may even be necessary to install two or more collectors, along with a more powerful fan to ensure adequate airflow. If collectors are shaded during part of the day (by tree limbs, for example), more collectors would be needed.

Remember! Whatever you do, be sure to seal up the leaks in your home and beef up the insulation first.

Does Solar Hot Air Make Cents?

Bill Hurrle of Bay Area Home Performance in Wisconsin notes that the best his company’s solar hot air systems can achieve (in their cold, cloudy climate) is a 25% to 35% annual reduction in heat bills.

Although this may not sound impressive, that reduction could cut fuel bills by $200 to $270 per year. And greater savings can be achieved in sunnier climates. As a rule, active solar heating systems are most cost effective in cold climates with good solar resources. But they also make sense elsewhere. A good solar installer will help you determine if a solar hot air system makes sense. Or, you can run the numbers yourself.

One popular way of determining the cost-effectiveness of a solar system is to calculate the return on investment. Return on investment is determined by dividing the annual savings by the cost of the system. If a $2,100 system saves $300 per year in heating bills, the return on investment is $300/$2100 or 14.3%. Manufacturers estimate returns on investment of 12.5% to 25% (based on current energy prices).

To accurately calculate return on investment, you should take into account the rising cost of fuel and any interest you pay on money borrowed to purchase the system, or lost interest if you withdraw the money from a savings account.

To get an even more precise number, maintenance costs should also be added to calculations of return on investment. Fortunately, very little maintenance is required on a solar hot air system; they only have two moving parts: a fan or blower, and a backdraft damper. Fans or blowers may need repair or replacement, but not for 18–25 years. Backdraft dampers can also be counted on for many years of trouble-free service. The rest of the system should last 50 years or longer!

When calculating return on investment, however, don’t forget to check into financial incentives from state and local governments and local utilities. At this time, no federal incentives are offered for solar hot air systems unless they are dual-use systems — that is, systems that use some of the hot air to heat water for domestic uses. To avail yourself of these credits, however, the solar hot air collector must be SRCC (Solar Rating and Certification Corporation) certified.

Shopper’s Guide

Solar hot air collectors can be ordered online or purchased through a growing list of solar suppliers — companies that also install other solar systems such as solar hot water or solar electric systems. But shopper beware! “Marketing departments can make anything look good,” says Bill Hurrle. Watch out for too-good-to-be-true claims. “One collector won’t heat a home,” says Hurrle, despite what some salespeople may tell you.

Of the two types of systems, I personally like the closed-loop systems — collectors with glazed panels — for residential and most commercial applications. If you are heating a warehouse, barn, or less tightly sealed structure that doesn’t need much heat, you may want to consider a transpired solar hot air system. They are manufactured by a company called SolarWall.

Transpired collectors for residential structures have been pulled from the market for a number of reasons. As Steve Andrews notes, “Transpired air collectors appear to be very suitable for a range of commercial applications, but seem to present more challenges than opportunities in residential applications — either in existing or new-home applications.” One problem with residential applications is that transpired collectors introduce too much fresh air. While fresh air is required for wintertime comfort, these systems can pump thousands of cubic feet of air into a house every hour, resulting in too-frequent air changes. Air pumped into a house forces warm indoor air out through openings in the building envelope (discussed in Chapter 3). The subsequent loss of heat could waste a substantial portion of the heat produced by the collector or your heating system.

Moisture buildup in walls is another potential problem with transpired collectors. Open-loop systems draw outdoor air into a house, bringing a lot of moisture along with it. Because the incoming air has to go somewhere, these systems force the now-moist indoor air through cracks around doors, windows, light switches, electrical outlets, and other openings in the building envelope. The moisture can end up in the insulation in wall cavities, the attic, or the ceiling. As discussed in Chapter 4, moisture that collects in wall insulation greatly reduces its effectiveness. Even a tiny amount of moisture can decrease insulation’s R-value (its ability to retard heat flow) by half.

Moisture also promotes mold growth and can, over time, cause wood to rot. Decaying framing members may eventually collapse, resulting in structural damage in the walls of wood-framed houses.

Conclusion

Solar hot air systems can reduce heating bills and improve home comfort — if properly designed and integrated into a building. Shop carefully. I strongly recommend hiring a professional to install your system. Call solar hot water and solar electric installers in your area to see if they also sell and install solar hot air systems. Research their products and ask to see some installations and talk to their customers.

Before purchasing a solar hot air system, be sure to investigate local building codes and zoning ordinances. You may need a building permit. Also, check out neighborhood or subdivision covenants as well. They may prohibit solar systems (although many homeowners have successfully challenged their homeowner’s and neighborhood associations).

If a solar hot air system makes sense for your situation, you will be rewarded many times over. Once you pay off your investment, you’ll receive free heat for the life of the system. At that point, you can sit back and enjoy the Sun’s free heat and the savings, knowing your work is done. You won’t be cutting and hauling firewood to save money on your monthly fuel bill. Nor will you have to worry about the rising fuel costs that are plaguing your neighbors! And, you’ll be doing something positive to create a clean, healthy future.