Chapter 9: Solar Hot Water Heating

Many people are aware of solar hot water systems that heat water for domestic uses — such as showers, baths, and dishwashing. These systems are often economical, highly effective, and cheaper over the long haul than conventional water-heating systems. In fact, domestic solar hot water systems represent one of the best buys among all the solar technologies. The only solar technology that’s more economical is passive solar heating.

Solar hot water systems, often referred to as solar thermal systems, can also be designed to heat homes. However, solar thermal home heating systems require considerable upsizing and additional changes to generate and store heat to meet demands during extended cold periods.

As the cost of natural gas continues to rise, those who retrofit their homes with solar thermal systems to provide domestic hot water and space heat could save a sizeable amount of money and reduce their environmental footprint.

Because solar hot water home heating systems are complex, I’ll begin by discussing domestic solar hot water systems (DSHW) designed to heat water for domestic uses. I’ll concentrate on those systems that are the most reliable and cost effective. I’ll then cover solar hot water systems used for space heating. By the end of the chapter, you should have a good understanding of solar thermal systems and be able to talk with potential installers about the options for your particular situation. For those who want to learn more, I suggest reading Bob Ramlow and Benjamin Nusz’s Solar Water Heating.

As a friendly reminder, as with all other solar heating options, sealing the leaks in the building envelope, beefing up the insulation, and employing other efficiency measures, such as installing water-efficient showerheads, are the very first steps you should take in your quest for an economical and environmentally sustainable solar hot water heating system.

Types of Domestic Solar Hot Water Systems

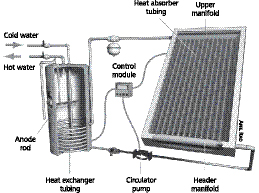

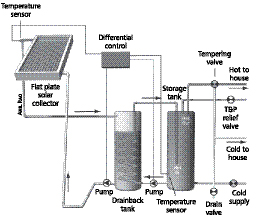

Most domestic solar hot water systems in use today in North America consist of two components: solar panels or solar collectors, and a large solar hot water storage tank (Figure 9-2). The solar collectors are typically mounted on the roof or on the ground in a location that receives full sunlight year round. The solar hot water storage tank is typically located next to the existing water heater so it can feed solar-heated water into its storage tank. In some homes, installers design systems with a single tank. Take a moment to review the system shown in Figure 9-2.

Fig. 9-2: In this system, a fluid is heated in the solar collectors when the Sun is out. This fluid is then pumped to a water-filled storage tank, located next to the domestic water heater. Heat is stored in the tank (in the form of hot water) until needed.

Solar thermal systems such as these are highly effective and, as noted earlier, are typically designed to supply about 40% to 80% of a family’s hot water. In extremely warm and sunny climates, a system could satisfy nearly 100% of a family’s needs.

As illustrated in Figure 9-2, copper pipes connect the solar collectors with the solar hot water storage tank. This circuit is known as the solar loop or the collector loop.

As discussed in more detail shortly, a fluid is pumped through the pipes and the collectors where it is heated by the Sun. This fluid can be either water or propylene glycol, a type of antifreeze. Propylene glycol never mixes with drinking water but is nontoxic and therefore safe to use should a leak develop in the system. The glycol solution used in solar hot water systems is designed to be heated to high temperatures without damage, so it can last 20 years or longer if the system is properly maintained. The fluid (water or glycol) that circulates through a solar hot water system is referred to as the heat-transfer fluid.

In many solar hot water systems, pumps, sensors, and controls are used to ensure that the system works automatically — starting up in the morning when sunlight warms the collectors and shutting down at night. Systems that require pumps to propel the heat-transfer fluid through the pipes and collectors are referred to as active systems. Simpler systems without pumps are known as passive systems.

Solar-heated water in a DSHW system typically feeds directly into a conventional water heater. When a hot water faucet is turned on, water flows out of the top of the tank of the conventional water heater and then through the hot water pipes to the faucet. Water drained from the conventional water heater tank is replaced by solar-heated water from the solar storage tank. If the water temperature in the replacement water (that is, from the solar storage tank) is at, or above, the setting on the thermostat in the conventional water heater, no additional heat is required. If the water temperature in the solar storage tank is lower than the water heater’s, the slightly cooler water from the solar storage tank will lower the temperature inside the tank of the water heater. When the water temperature inside this tank drops below a certain setting, the burner (in a gas or propane water heater) or heating element (in electric water heaters) will be called into duty, boosting the temperature to the desired setting. Either way, solar hot water reduces the demand for fuel required to heat a family’s water.

Solar hot water can also be fed into a tankless water heater. If the temperature of the solar-heated water is at or above the thermostatic setting, the burner in the tankless won’t come on. If it isn’t, the burner will kick in, raising the temperature of the solar-heated water to the proper temperature.

As noted above, some new solar thermal systems require only one tank. Water in this tank is heated by the heat-transfer fluid that circulates through the solar collectors. The heat it gains in the collectors is stripped off by a heat exchanger. A heat exchanger is a coil of copper pipe located in the wall or in the base of the tank or sometimes outside the tank. It allows solar heat to move from the heat-transfer liquid to the storage tank.

Domestic hot water is drawn directly from the tank. In these systems, the tanks are fitted with one or two backup electric heating elements. If it’s cloudy and the solar thermal system cannot generate enough heat to warm the water, the electric heating element(s) kick(s) in, ensuring sufficient hot water.

Single tank systems are easier to install, require less space, and are less expensive. If you have an electric water heater that needs replacement or are installing a system in a new home in which you were anticipating using electricity to heat your water, this may be the system for you. Bear in mind, however, that natural gas is much less expensive and more environmentally sound than electric heat. If your electricity is supplied by a solar electric system, however, the environmental concerns of the electric heating element in the water tank should be greatly diminished. Bear in mind, however, that electric heating elements draw around 4,500 to 5,500 watts and therefore consume a significant amount of energy. Unless your solar hot water system produces most of your domestic hot water, the electrical demand could easily overwhelm a fairly large solar electric system.

Direct and Indirect Systems

Active and passive domestic solar hot water systems can be designed as either direct or indirect systems. Direct systems heat the actual water that occupants of a building consume. That is, the water consumed in a house circulates through the collectors. It is stored in a tank that feeds directly into the hot water pipes of a house. Direct systems are also referred to as open-loop systems.

Indirect systems, in contrast, heat a fluid that then heats the water that comes out of the faucet. In these systems, heat-transfer fluid is heated by the Sun in the collector. Its heat is transferred to water in the solar storage tank after it passes through a heat exchanger. As noted earlier, the heat exchanger may be located in the solar storage tank, alongside it, or underneath it. When hot water is required, it flows out of the conventional water heater. Water drained from this tank is replenished by solar-heated water stored in the solar storage tank.

Indirect systems such as this are referred to as closed-loop systems. The term “closed loop” refers to the fact that the heat-transfer fluid is in a separate set of pipes and never mixes with drinking water.

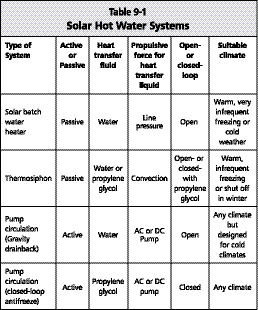

Solar Batch Systems

DSHW systems fit into three broad categories: solar batch hot water systems, thermosiphon systems, and pump circulation systems. Some of them are active; some are passive. As shown in Table 9-1, solar batch systems are open-loop systems, while thermosiphon and pump circulation systems may be either open- or closed-loop, that is, direct or indirect.

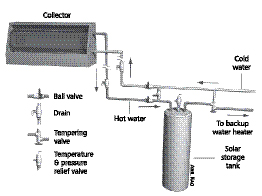

Let’s begin with the simplest of these systems, solar batch hot water systems. As shown in Figure 9-3, solar batch hot water systems, or simply batch systems, combine water collection and storage in one unit. That is, the solar collector and storage tank are housed together. Even though solar batch systems are not used in solar space-heating systems, it’s a good idea to take a quick look at them. This will help you better understand how solar hot water systems work.

Fig. 9-3a: In this system, water is heated in a tank or series of large pipes inside a collector located on the roof or ground next to a building. Hot water flows directly out of the tank when a hot water faucet is turned on.

Solar batch water heaters are popular in many tropical countries such as Mexico, or desert nations like Israel — areas that remain hot year round. Solar batch water heaters are rather simple devices. In tropical countries, a batch collector usually consists of a single black water tank mounted on the roof of a building. The tanks are painted black, so they absorb more sunlight energy, improving their efficiency. During the day, solar energy heats the water inside the tank. When a hot water faucet is turned on, solar-heated water flows out of the top of the rooftop tank into the hot water supply line that runs directly to the faucets inside the building. Cold water enters the bottom of the tank, replenishing the water drawn out from the tank. Gravity propels hot water down the pipes, and cold water is propelled up into the tank by line pressure. As a result, no pumps are required to move water in this system. Because the water heated in the tank is used inside the building, solar batch hot water systems are classified as direct, or open-loop, system.

Fig. 9-3b: This diagram shows the components of a solar batch water heater.

Solar batch heaters in use in many more developed countries are considerably more sophisticated than the black roof-mounted tanks you will see in Central America. As shown in Figure 9-3, storage tanks are typically located inside a collector — an insulated box that helps hold in heat at night.

In many countries, the solar batch water heater is usually plumbed into a home’s conventional water heater. (That is, it feeds hot water to the conventional water heater.) Therefore, when a hot water faucet is turned on in the house, water is drawn directly from the conventional water heater. Replacement water flows from the solar batch water heater into the tank of the water heater. On hot sunny days, solar batch water heaters produce extremely hot water, so the conventional water heater never kicks on. To prevent scalding, installers place a mixing valve (also called a “tempering” valve) between the hot water line exiting the water heater and the cold water line feeding the collector. If the water leaving the tank is too hot, the valve opens, permitting cold line water to mix with the hot water, bringing the temperature down to a comfortable level.

On cool, cloudy days, when the temperature of the water in the batch heater is below that in the conventional water heater, the conventional water heater turns on, boosting water temperature. The cooler water flowing into the tank from the batch heater is therefore, raised to the desired setting (usually around 115–120° F/46–49° C). On these days, the batch heater preheats the water that flows into the storage water heater tank. This saves energy because the water from the solar batch water heater is usually much warmer than the water coming in from a well or from the city water supply.

Drawbacks of a Solar Batch Water Heater

Although solar batch water heaters are economical and highly reliable, they do have some drawbacks. One of the most important is that they can only be used in warm climates — areas like Florida that rarely, if ever, experience freezing temperatures. That’s because the solar water storage tanks and water lines connecting them to the house are located outside, where they could freeze. Freezing temperatures cause water in the pipes and collectors to expand, creating enough force to crack a copper pipe. When the pipes thaw, water bursts out.

Another problem is that, even in warm climates, solar batch collectors lose heat to the atmosphere at night or on cool, cloudy days. The hottest water is, therefore, typically available in the afternoons and the early evenings. To use a system like this, you would most likely have to shift your use of hot water to the times when water inside the collector is at its maximum temperature.

On the plus side, batch heaters have no moving parts, electronic controls, or sensors and are therefore the most reliable solar water heating systems on the market. Another positive consequence of their simplicity is that they are much less expensive and much easier to install than other types of systems. Because they’re free of electronic controls, sensors, and pumps, they also require no electricity to run. They operate on line pressure — water pressure in the pipes of your home.

Thermosiphon Systems

For a system that performs admirably year round, solar designers separate the collection and storage functions. More precisely, they place the collection unit (the solar collectors) on the outside of the house (usually on the roof) where they can absorb solar energy all day long. They place the storage tank inside, where it is much warmer and not subject to freezing. As a result, these systems can operate efficiently even in the coldest weather.

Separate collection and storage systems make up the bulk of the solar hot water systems in use today. The most basic of these is known as a thermosiphon system (Figure 9-4). It consists of a collector, a storage tank, and pipes connecting the two. Instead of relying on a pump to propel solar-heated water from the collector to the storage tank, water flows by convection. (Convection occurs when a fluid is heated. The heated fluid expands, becomes lighter, and thus naturally rises.)

Fig. 9-4: In this system, a liquid inside the collector is heated. Heated fluid expands, becoming lighter, then rises, creating a thermosiphon. That is, it draws cooler liquid in from below, creating a convection loop.

Figure 9-4 shows the anatomy of a thermosiphon solar hot water system. As illustrated, the heat-transfer liquid in the collector is warmed by sunlight. It then rises and flows out of the solar collector to the solar storage tank. The flow of heated liquid out of the solar collector, in turn, draws cooler fluid into the bottom of the collector.

In these systems, heat “pumps” the fluid from the collector to the storage tank. This natural pumping action is created by convection, and is known as a thermosiphon pump. Convection continues to pump fluid through the system so long as the fluid in the solar collector is hotter than the fluid in the bottom of the solar storage tank.

The convective flow of liquid in this system is a simple, non-mechanical thermosiphon pump that operates during daylight hours. However, for the thermosiphon to operate, the storage tank must be about two feet above the solar collector. Accordingly, the solar collectors are typically installed on a ground-mounted rack, so they are below the hot water storage tank.

Thermosiphon systems employ either water or a nontoxic antifreeze, propylene glycol, as the heat-transfer fluid. Water is often used in systems installed in areas where freezing does not occur. In these systems, water heated in the collector flows directly into the solar hot water storage tank. In open systems, hot water from the solar hot water storage flows into a conventional water heater when a hot water faucet is turned on.

Propylene glycol is used in thermosiphon systems installed in colder climates — places where freezing temperatures are encountered. In these systems, propylene glycol travels from the collectors to a heat exchanger located in or near the solar hot water storage tank. As the solar-heated liquid flows through the heat exchanger, heat is transferred from the glycol to the water in the tank. Cooled glycol flows back to the collector to be reheated.

Open-loop thermosiphon systems (those that use water as the heat-transfer fluid) are relatively simple, inexpensive, and trouble-free. Closed-loop systems (those that use propylene glycol as the heat-transfer fluid) are more complicated, in large part because of the addition of a heat exchanger.

Pump Circulation Systems

The most widely used solar hot water systems in developed countries are pump circulation systems. They are similar to the thermosiphon system, except that the driving force — the force that moves the heat-transfer liquid — is a small electric pump.

Solar collectors in pump systems are usually mounted on roofs, and less commonly on the ground near the building. The solar hot water storage tanks are located inside the house, next to a conventional water heater — typically a storage water heater. An electric pump propels the heat-transfer liquid up through the collectors where it is heated by the Sun. The heated fluid then flows back to the thermal storage tank, where the heat is deposited.

As in thermosiphon systems, pump-driven systems use either water or propylene glycol as the heat-transfer fluid. If water is used, the system can be designed as an open-loop system — that is, a direct system. Although open-loop systems have their advantages, freezing may occur in cold climates. To prevent pipes from freezing and bursting, designers developed a gravity drainback system, simply referred to as a drainback system. Figure 9-5 shows a drainback system.

Fig. 9-5: In this drainback system, water is the heat-transfer fluid. It circulates through the system thanks to a small electric pump.

Gravity Drainback Systems

To understand how these systems work, let’s begin at sunrise. As the Sun heats the solar collectors, a temperature sensor located at the top of the collector (see Figure 9-5) activates a pump near the storage water tank. It pumps water out of the storage tank through the solar collectors. As water flows through the collector, it warms up. As water cycles through the solar loop between the storage tank and the collector, it gets hotter and hotter.

Another pump, also shown in Figure 9-5, circulates water out of the conventional water heater (right) through a heat exchanger located in the solar hot water storage tank. Heat stored in the latter is thus transferred from solar-heated water to household water (in the conventional water heater).

Water continues to circulate through both loops of the system (the collector loop and storage tank loop) until the Sun goes down. At that point, the system shuts down. The pumps turn off. To prevent water from freezing and damaging pipes, however, all the water in the pipes and collectors drains out of them. It empties into the solar storage tank by gravity — giving the system its name, gravity drainback.

The pumps in drainback systems are controlled by a controller, a small logic circuit that is wired into a temperature sensor located in the solar collectors. When the Sun goes down, the temperature of the liquid in the collectors immediately begins to fall. The sensor then sends a signal to the controller, and the controller switches off the circulating pumps.

Pros and Cons of Gravity Drainback Systems

One advantage of gravity drainback systems is that they can be used in all climates — even extremely cold ones. They’re a bit simpler and therefore less expensive than glycol-based active systems. Another advantage is that they do not require propylene glycol. As you shall soon see, propylene glycol may deteriorate due to high temperatures if the system sits idle for long periods (for example, while a family is on a prolonged vacation or if the pump breaks down and is not repaired quickly). When this occurs, the glycol needs to be drained and replaced. Glycol currently costs about $50–$60 per gallon, and systems require three to five gallons, depending on the length of the pipe run and the number of collectors. Glycol is typically replaced by a trained professional, which adds to the cost of this maintenance.

On the downside, drainback systems require the largest pumps of all solar hot water systems. In addition, although they are designed to drain when the pumps stop, there is still risk of damage from freezing. So, they may not be the best option for the coldest of climates. In such instances, installers may use a mixture of propylene glycol and water to provide a greater degree of freeze protection.

Another downside is that gravity drainback systems aren’t good in areas with hard water. Calcium deposits in the pipes can clog the system. Distilled water should be used in the solar loop, but it requires special fittings.

Another disadvantage of drainback systems is they can’t be used on buildings taller than two stories because the pumps can’t move water any higher.

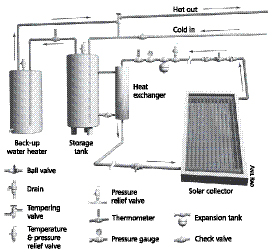

Closed-Loop Antifreeze Systems

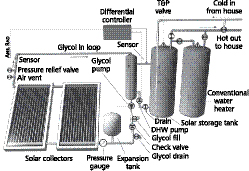

Although drainback systems work well in cold climates, most active systems are glycol-based pump-driven systems. These systems require a heat exchanger to transfer heat from the glycol to the water inside the solar hot water storage tank. As noted above, heat exchangers may be located inside the solar hot water storage tank, alongside it, as shown in Figure 9-6, or underneath, it. These systems also require components not found in other DSHW systems, for example, an expansion tank as shown in Figure 9-6. Glycol expands when heated. The expansion tank accommodates the hot glycol, preventing pressure from building to dangerous levels in the solar loop.

Fig. 9-6: In this pump-driven, glycol-based system, propylene glycol is the heat-transfer fluid. It circulates through the collectors. Heat is transferred from this fluid to the water in the storage tank via a heat exchanger.

Pros and Cons of Glycol-Based Systems

Closed-loop antifreeze systems are popular and reliable. They work well in all climates, and in cold climates they provide excellent protection against freezing. On the downside, closed-loop systems are the most complex and therefore the most costly of all solar hot water systems. In addition, they have more parts and, therefore, there are more chances for things to go wrong. As noted earlier, the propylene glycol may need replacement if the glycol routinely overheats, which may occur if the circulating pump breaks down or a family is away from the home during the summer for a protracted period. During such periods, hot water is not removed from the solar storage tank. This causes the system to shut down, so the glycol doesn’t circulate through the collector loop. Glycol that sits in the pipes in the collector overheats and turns black and viscous. One way to prevent this problem is to program the controller to circulate in reverse at night. This bleeds heat out of the storage tank so the system continues to operate (glycol circulates through the collectors during the day).

Solar Collectors

Now that you understand how solar hot water systems operate, let’s take a brief look at the solar collectors. There are two types of collectors used in solar hot water systems: flat-plate and evacuated-tube.

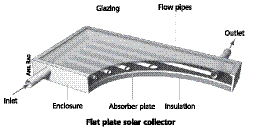

Flat-Plate Collectors

The flat-plate collector consists of a glass-covered insulated box. Inside are copper pipes attached to a flat absorber plate — all coated by a highly absorbent black material, known as a selective surface. A selective surface is so named because its color and surface texture allow it to absorb sunlight much more efficiently than conventional black surfaces. Because of this, collectors with selective surface absorber plates are more efficient — they can convert more solar energy into heat.

Sunlight consisting of visible light and heat (infrared radiation) enters a flat-plate collector (Figure 9-7). Visible light is absorbed by the dark-colored absorber plate, where it is converted to heat. Heat waves (infrared radiation) heat the collectors directly.

Fig. 9-7: Propylene glycol or water circulates through the pipe in this panel, removing heat from the collector and transferring it to a water storage tank.

Flat-plate collectors are the most commonly used of all collectors, and they are useful for applications that require water temperatures under 140° F (60° C), notably domestic hot water systems. They’re also useful for many space-heating applications, notably forced hot air and radiant floor heating systems. Unfortunately, they don’t achieve the high temperatures required for baseboard hot water systems.

Evacuated-Tube Collectors

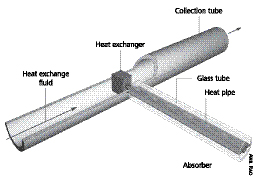

An evacuated-tube collector consists of 20 to 30 long, parallel glass or plastic tubes. Inside each tube is a copper pipe connected to a copper fin to increase its surface area. Both are coated with a selective-surface material to increase solar absorption and heat production. When sunlight strikes the collector, heat is absorbed by the pipe and fin and is transferred to the heat-transfer fluid inside the pipe.

Evacuated-tube collectors get their name from the fact that air is pumped out of the glass or plastic tube, creating a vacuum. Interestingly, vacuums are great insulators. (That’s why thermos bottles work so well.) The vacuum helps hold solar heat inside the collector, even on cold days, which improves their efficiency and permits greater solar heat gain.

Fig. 9-8: Glass tubes contain a heat-absorbing pipe and fin that absorb the Sun’s energy, transferring it to a heat-absorbing liquid. When heated, it rises to the top of the unit, to a heat exchanger, as shown here.

Evacuated tubes operate, in part, passively. When sunlight strikes the collector, a fluid inside each copper pipe flows upward by convection (passively) to a heat exchanger located at the top of the collector (Figures 9-8 and 9-9). Here, heat is transferred to another heat-transfer fluid that is actively pumped through the system. It carries the heat to a solar hot water storage tank, where it is stored for later use. The cooled fluid returns to continue the cycle, continually drawing heat off the collector tubes.

Fig. 9-9: Heat collected by each tube is transferred to propylene glycol flowing through the heat exchanger, as shown here.

Evacuated-tube solar collectors perform well in many climates. Manufacturers routinely claim that they outperform standard flat-plate collectors by absorbing and retaining more sunlight energy. This, in turn, increases their efficiency and hot water production. Bob Ramlow, a solar thermal water system expert and senior author of Solar Water Heating, pointed out to me that “there’s a lot of hype about evacuated-tube solar collectors,” making it imperative to consider their pros and cons carefully. For example, while the vacuum in a collector acts as an insulator that helps reduce heat loss from the inside of the collector tubes and therefore increases hot water production, in regions with frequent snows, evacuated tube solar collectors shed snow poorly. This is especially true when the collectors are mounted parallel and close to a roof. Because they retain heat, the snow tends to cling to the collectors, not melt off, as it would in a standard flat-plate collector. In addition, Ramlow points out, some of the older designs have been known to lose their vacuum. This reduces their efficiency, although, as Ramlow says, some manufacturers have modified their designs to prevent this problem. Needless to say, it is important to select a collector that has been designed and built to prevent the loss of vacuum.

Besides these problems, Ramlow notes that numerous side-by-side comparisons have shown that evacuated-tube collectors do not outperform flat-plate collectors, despite manufacturers’ claims. Nor do they perform any better than flat-plate collectors in “less-than-optimal regions” — that is, in cloudy areas.

Not everyone completely agrees with Ramlow’s assessment. Evacuated-tube solar collectors do perform better than flat-plate collectors in many circumstances, says Henry Rentz, owner of Missouri Valley Renewable Energy. He has installed solar hot water systems for a dozen years. David Sawchak of Morningstar Enterprises, who has been in the solar hot water business since the 1970s, agrees with Rentz. They’re especially useful for high-temperature applications, like baseboard hot water systems. As noted above, baseboard hot water systems require higher temperatures than either forced-air space-heating systems or radiant floor heating systems.

Both experts point out, however, that it is important to consider your choices very carefully. Be sure to consult with a local solar hot water expert — one who really knows what he or she is talking about — to determine if an evacuated-tube solar hot water collector makes sense in your area and for your application.

Ramlow notes that evacuated-tube collectors will produce water as hot as 220° F, compared to 180° F for flat-plate collectors. Although this may seem advantageous, water can boil in the storage tank (typically, when families go on vacation during the summer). Rarely will water boil in a flat-plate collector system. To protect against this, you should consider installing a larger storage tank if you install evacuated-tube collectors.

“When investing in evacuated-tube collectors, a buyer must pay particular attention to quality because while some of the highest rated collectors are evacuated-tube type, most of the lowest rated collectors are also evacuated-tubes,” Ramlow says.

Solar Hot Water Space-Heating Systems

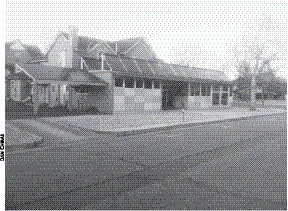

Now that you understand which domestic solar hot water systems are typically installed and how these systems work, it’s time to take a look at solar hot water heating systems. Solar hot water heating systems are larger and a bit more complex than domestic solar hot water systems. While a domestic solar hot water system — designed to provide hot water for showers, dishwashing, and the like — typically has two to four collectors, a system designed for space heating typically uses eight or more solar collectors Figure 9-10. These systems also employ a much larger storage tank; instead of 90 gallons, they may require 180 up to 1,000 gallon storage tanks. Large tanks are needed to store the large quantities of solar-heated water required to heat buildings.

Fig. 9-10: This space-heating system on an architectural firm in Colorado Springs uses numerous evacuated tube solar collectors. One of the main problems with systems like these is that they produce a surplus of hot water during the summer.

Solar hot water space-heating systems are active systems. That is, they are pump-circulation systems. These systems may be either drainback or glycol-based. As just noted, solar heat is stored in water tanks; though it can also be stored in beds of sand. I’ll start with water storage systems, as they are the most common type.

Drainback Solar Hot Water Heating Systems

In a drainback solar hot water space-heating system, the design includes one large storage tank or a single drainback tank plus one or more storage tanks to hold hot water for times of need. Most systems have one large, extremely well-insulated tank (typically 200 to 1,000 gallons). This tank is typically filled with distilled water. As Bob Ramlow notes, be sure to use distilled water in the collector loop. Never use tap water. It contains minerals that will deposit on the inside walls of the pipes and collectors, obstructing flow and reducing the efficiency of the system.

On sunny winter days, the water in the storage tank circulates through the collectors, becoming hotter and hotter. However, when clouds obscure the Sun or the Sun sets, the system shuts down. All the water in the collectors and pipes drains back into the storage tank. If the home requires space heat, hot water inside the solar storage tank is there to provide it.

To understand how heat is stripped out of hot water inside the storage tank, consider an example. Imagine we’ve installed a solar hot water space-heating system in a house previously heated by a forced-air furnace. In such systems, a furnace heats room air passing through it, using natural gas, propane, oil, or electricity. The hot air is circulated through supply ducts in the house. Cold room air returns to the furnace via cold air returns (ducts that run through walls, attic spaces, and under floors). When the cold air reaches the furnace, it is reheated.

When a solar hot water system is added to a home such as this, when space heat is required, heat is drawn principally from the solar storage tank if the water inside the tank is sufficiently hot. The furnace serves as a backup. Here’s what happens: when the thermostat in the house calls for heat, solar-heated water flows out of the storage tank through a heat exchanger installed inside the duct that normally carries hot air out of a furnace. The furnace fan turns on and blows cool return air over the heat exchanger. The cool air blown over the surface of the heat exchanger strips the solar heat from it. The solar-heated air is then distributed through the house via the existing supply ducts in the house. The solar storage tank continues to provide heat, circulating hot water through the heat exchanger in the furnace, so long as it is needed, and so long as there’s enough hot water in the tank. If the water temperature inside the tank drops below the desired setting, the gas furnace turns on, taking over. As noted earlier, it provides backup heat to the solar system. All this is controlled by a logic circuit, a small computer. It is fed temperature information from the thermostat and sensors located at strategic locations in the system, for example inside the solar storage water tank.

Drainback systems work well in solar home heating systems, supplying space heat and heating water for domestic consumption. Bear in mind, however, an additional heat exchanger is needed to provide heat to a family’s conventional water heater (or tankless water heater).

Glycol-Based Systems

Glycol-based systems tend to be the system of choice for space heating, especially in cold climates. In these systems, solar heat can be stored in a single large tank, in multiple storage tanks, or in beds of sand from which the heat is later extracted and delivered to the home’s heating distribution system — either ducts or pipes.

Designs of closed-loop glycol-based space-heating systems are identical to those described for domestic solar hot water. However, as in drainback systems, most solar home heating systems employ a single large, extremely well-insulated water tank located in a basement to store solar-heated water. This tank is heated by the solar-heated glycol that circulates through the collectors. The heated glycol circulates through the collectors and then through a heat exchanger inside the storage tank, where the heat the glycol has absorbed is transferred to the water.

Heat drawn from the storage tank is distributed via pipes to a heat exchanger in forced-air systems, as described above. It can also be circulated through pipes in the floor in radiant floor systems, or pipes that lead to baseboard heaters in baseboard (hydronic) hot water systems. Heat is drawn out of the solar storage tank via a heat exchanger.

If the system is designed for domestic hot water, too, a separate heat exchanger is installed inside the storage tank. It feeds hot water to a domestic water heater — either a tankless water heater or a conventional storage water heater.

Pumps in glycol-based systems can be run by household current or by electricity produced by a PV module mounted near the hot water collectors (Figure 9-11). This is known as direct PV, because the photovoltaic module is wired directly to the pump that circulates glycol through the solar loop. Although PV modules work well, they have some limitations. One of the most significant is that they are unable to lift the heat-transfer fluid more than a single story. You won’t be able to install one on a two-story home. When in doubt, ask a local expert for his or her opinion.

Fig. 9-11: This PV module powers only the circulation pumps in the solar hot water system, not the fans or pumps required to distribute heat through a home’s heating system.

One of the main disadvantages of solar hot water space-heating systems is that they are sized to produce heat in the winter when solar gain is minimal and heat demand is high. Throughout the rest of the year, however, the demand for heat is minimal — or nonexistent. Consequently, solar thermal systems designed for space heat produce a lot more hot water than is required. To prevent water in the storage tanks from boiling in the off-season — late spring, summer, and early fall — designers typically install a dump load — a place to dump excess heat during the summer. Excess heat can be diverted to pipes buried around the perimeter of a home. Heat flows out of the pipes into the ground, warming it. If designed correctly, this heat can move into a home — through the basement walls — during the winter, keeping it warmer. Insulation buried over the pipe helps retain heat, making it available during the winter.

Heat can also be dumped into hot tubs or swimming pools to lengthen the swim season. In addition, heat can be dumped in very large and extremely well-insulated stainless steel storage tanks buried in the ground. Some of this heat can be drawn off in the winter by heat exchangers and used to heat the home in the winter. Alternatively, heat can be dumped into insulated sand beds in the ground around or under a home. To learn more about heat dumping, check out Chuck Marken’s article “Overcoming Overheating,” published in Home Power, 142, 2011.

With this downside in mind, my advice is to think long and hard about installing a solar hot water space-heating system. As you have seen, they are useful only during the heating season. If you are in an area that has a long heating season, the system will make a lot more sense than if you live in an area with a relatively short heating season.

A Word on Storage Tanks

Storage tanks for solar hot water space-heating systems should be well built and durable. They must be made of materials capable of storing water for long periods at 180°F or higher (if evacuated tube collectors are installed). High-temperature fiberglass tanks work well as do insulated stainless steel dairy tanks. Beware of homemade steel storage tanks and wood-framed tanks lined with plastic or rubber roofing materials (EPDM). They may be inexpensive to build, but they don’t last very long. Ordinary storage water heaters aren’t such a good idea either. Conventional water heater tanks are damaged by high-temperature water.

Ideally, tanks should be seamless and jointless to reduce the possibility of leakage. They also have to be sized so they can be carried into a home without cutting out a wall! Larger fiberglass tanks come in pieces so they can be assembled inside the building.

For years of leak-free performance, it is recommended that pipes enter and exit at the top of the tank, rather than from fittings located along the bottom. If you want to learn more about tanks, I recommend Bob Ramlow and Ben Nusz’s book, Solar Water Heating. It has an excellent chapter on solar space heat. (Tom Lane’s book, Solar Hot Water Systems, is another excellent, although much higher level, book — great for those who are thinking about getting into the business.) You can also consult with installers in your area.

As noted earlier, it is also possible to store solar heat in sand beds. To do this, hot water is circulated through pipes embedded in insulated sand beds, often under the concrete slab of a home. These systems do work, if designed and installed correctly. Ramlow and Nusz’s book discusses them in detail.

Another option for heat storage, though, is to pump heat into the concrete slab of a building. The heat is delivered directly from the collectors into a set of pipes embedded in the slab during construction. These systems provide radiant floor heat and work well in extremely cold climates. Be sure to insulate under the slab and around the perimeter of the foundation. During the summer, you may need to divert heat to a dump load, for example, pipes buried in the ground outside to prevent overheating, or a large insulated storage tank buried in the ground under or alongside the house.

Choosing the System to Meet Your Needs

Despite the many options, it’s not difficult to select a solar hot water heating system that will work for you. If you live in a freeze-free climate, you should consider a drainback system —an open-loop, pump circulation system. Remember that open-loop drainback systems are not generally recommended in regions with hard water because minerals in hard water can deposit on the inside of pipes in the solar loop. Over time, mineral deposits can reduce flow rates and the efficiency of a system. In colder climates or in regions with hard water, your best bet is a closed-loop glycol-based system.

Conclusion: Sizing and Pricing aSolar Hot Water Heating System

Before sizing a solar thermal home heating system, as with any system, it is important to make your home or business as efficient as possible. How large a system you need depends on many factors, including wintertime temperatures, the amount of sunshine you receive, how energy-efficient (airtight and well insulated) your home is, and temperature requirements (do you require the temperature cranked up to 80° F to stay warm?).

Your best bet is to call local installers who will assess your heating requirements, the energy-efficiency of your home or business, solar availability, and other factors, then recommend a system size. A small home-sized system for an efficient home in a sunny climate could cost as little as $12,000; a larger system for an energy-inefficient home with poorer solar resources could cost many times more — $50,000, even more.

The economics of the investment, however, are generally quite favorable — that is, these systems are usually a good investment. The return on investment depends in part on the type of heating system you are currently using. If you are replacing electric heat with solar heat, the investment is almost always sound — as it is extremely costly to heat with electricity. Replacing propane heat with solar heat can also be quite cost effective, too. Replacing natural gas with solar heat may have a lower return on investment, although natural gas costs have increased dramatically in the past ten years and are expected to continue to rise.

Don’t forget that in the United States there are economic incentives from the federal government for solar hot water systems. You can receive a 30% federal tax credit for installing a solar hot water system.

State or local incentives may also be available. A local installer can give you the rundown on state, local, and federal incentives. Or, you can check www.dsireusa.org to see what’s available in your state.