Figure 3.1

The competition-winning De La Warr Pavilion by Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff at Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex (1934): the pretext for the Architects’ Journal’s move to modernism. Courtesy of the author.

3 Bullies and Sissies

Fascists, Communists, and Margaret Thatcher

Right at the start of the introduction we saw Pugin shouting down a scheme by Basevi for new buildings at Balliol College, Oxford, and in chapter 2 he was rubbishing other architects. In the twentieth century violent attacks became the normal way of talking about buildings. Early-century manifestos by polemicists—Loos, Le Corbusier, Gropius—provide rich examples, and the fact that modernist architectural historians, unlike everybody else, generally like to write in terms of revolutions and breakthroughs, and post-rationalized intellectual debates, rather than slow developments, has reinforced and established them. Until recent times student crits were aggressive events where guest critics vied with tutors to make the cleverest, nastiest remarks they could; presumably this stopped when boys began to cry as well as girls, and students were invited, in the public universities at any rate, to fill out feedback forms on the quality of the response they were receiving from their teachers. One event that sticks in my mind came when a tutor at the The Bartlett School of Architecture encouraged us during the course of a fifth-year crit to comment on a fellow student’s scheme. We were designing a city airport for London. “Why is there such a contrast between the width of the circulation areas in the departure hall, and the narrowness of the route from the departure hall to the boarding gate?” I asked. This was met with silence from the crittee. When it was my turn to put my work up on the wall, that same student rubbished it time and time again, in waves of fury. He is now the named partner of one of the best-known architectural practices in the world, so there is little doubt which of us came out the loser.

Certain aspects of design always attracted a vicious response from any critic who happened to be looking at it. At Cambridge we had two students who insisted on designing in a neo-Georgian style. They never got any kind of reasonable response from their tutors; this in a department with a fabulous library collection of books on neoclassical architecture a few seconds’ walk from the studio. No tutor ever said to them: “Go and look at . . .”. Not once, as I recall. And of course the more the tutors attacked them, the more defensive they grew about their ideas, so that they became in effect unteachable and untaught. I designed a scheme in my first term—October 1979—in what I hoped would be a Ralph Erskine kind of style—I loved Clare Hall, the postgraduate college on the other side of the River Cam—and I was given a personal lecture by a visiting critic about the evils of Margaret Thatcher, recently elected. The pretext for this appeared to be that my building was not abstract, white, and rectangular (as opposed to abstract, white, and a funny shape, the late-modernist alternative). I think the rationale was as follows: Thatcher, controversially among liberals, opposed the building of public housing, and public housing was largely uniform in style, so a person who designed housing in a more colorful way was therefore some kind of libertarian nut-job. Looking back, I can see that I was irritating as a student. I used to tell people that I preferred the Cambridge University’s elevated faculties building designed by Casson, Conder and Partners off Sidgwick Avenue to James Stirling’s neighboring and famous History Faculty—then in a process of accelerated decay, with tiles flying off and nasty chemical reactions going on around the windows—and when he heard this, my director of studies told me that this was “proof that I wasn’t fit to be an architect.” If you make the argument in favor of Casson Conder now—and I have heard fashionable critics doing it—you are praised for your sensitivity to English Scandinavianism. There is no particular reason why teachers should be soft on students who need discipline—who sometimes need a boot up the backside to learn to look, to analyze, to research, to think—but on the other hand, the sliding into narrow political polemic, unrelated to anything visual, and the closing down of areas of discussion, is unlikely to do much good either.

The business about Margaret Thatcher is a significant one, because it is typical of the mid- to late-twentieth-century process of automatically associating a style with a political movement: neoclassical = Speer, as it were. The fact that architectural debate is certainly political does not justify a cheap and lazy association of a style or an attempt at it with a complete and unrelated political attitude.1 If you know that an individual votes for a certain party, you still know very little about that person, and virtually nothing at all about their creative instincts; as I have said before, in my experience everything about an architect, from their clothes to their politics and their religion, is derived first and foremost from their architecture.

Looking back through old journals, it appears that there was one key moment when the architectural press seems to have made a concerted effort to establish a link between architecture and politics, and used it effectively to change the way in which buildings were talked about. This came when Erich Mendelsohn won with Serge Chermayeff the competition to design an entertainments pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea, in Sussex on the south coast of England, in 1934. By reprinting some letters on the competition from members of the British Union of Fascists that had previously appeared in small-circulation local and political newspapers, the Architects’ Journal, the weekly paper then widely read by British architects, conjured up an artificial storm for its own quite different readership. Earlier in the year it had published letters by, and addressing comments from, a prominent British fascist, and the Bexhill business gave its writers an opportunity to air their politics again.

The editor of the Architects’ Journal was the proprietor’s son, Hubert de Cronin Hastings, who himself took a political stance on architecture, but since 1934 his small team had been joined by J. M. Richards, a neighbor and friend of Mendelsohn, a pro-modernist and a Communist sympathizer.2 At the time of the Bexhill competition, the pages of the Journal were full of neo-Georgian town halls and even the occasional rustic cottage—in this respect it was somewhat old-fashioned when compared to its drier professional rival, the Architect & Building News. This had already gone modernist; the assistant editor was Richards’s friend John Summerson, with whom the former saw himself in friendly rivalry. It seems likely that Richards, who soon had a “growing role” at the magazine, managed the Bexhill story, and perhaps it was he who had recently found the Bexhill Pavilion “virile”—a compliment, of course—by comparison to the latest batch of municipal Georgiana in the journal’s unsigned Notes and Topics column.3

Figure 3.1

The competition-winning De La Warr Pavilion by Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff at Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex (1934): the pretext for the Architects’ Journal’s move to modernism. Courtesy of the author.

Mendelsohn’s design was published in February 1934, when there would have been considerable interest among British architects in the fate of their profession under fascism; but the way in which the Architects’ Journal managed to prolong the subject of the pavilion in its correspondence columns over the period that followed hints at a calculated intention of softening up its readership for the magazine’s wholesale conversion to modern architecture. The fascist, or at any rate xenophobic, reaction to Mendelsohn provided the editors with an effective Aunt Sally. In January 1935 it published, for example, a letter from a Keith Aitken of Cardiff, who, we read, observed:

The tragedy of the Jew appears to be his unfailing ability to arouse antagonism wherever he goes . . . we must be on our guard against too readily drinking in Jewish-Communist doctrine, even when it is disguised in the most seductive of concrete and glass clothes.4

As the Architects’ Journal recognized, the antagonism to Mendelsohn was not really based on the foreignness of his architecture. All the published runner-up schemes for Bexhill were provincial, fairground versions of the style that Mendelsohn himself had invented, including a second-placed scheme by the fascist sympathizer Marshall Sisson with James Burford; it seems hardly surprising that he could do it better than his competitors. The real challenge to Mendelsohn was his foreignness, if not his Jewishness. This episode enabled the magazine to portray the enemies of international modernism as simultaneously the enemies of liberty and progress, or even as xenophobes and anti-Semites; there were plenty of liberal correspondents to agree with the editorial line. By 1935 there were enough modernist projects around for Richards and Hastings to publish at least one every week, and Richards departed to continue his work at the monthly Architectural Review, the Architects’ Journal’s sister magazine. In 1951 he became a long-serving member of the influential Royal Final Arts Commission, the body that then bestowed de haut en bas backing to major or controversial architectural projects, a position from which he was able to continue his campaign for modernism until a volte-face that seems to have occurred by 1972.5

A sad footnote to the Bexhill affair is that Richards soon joined the long list of people who had taken a dislike to Mendelsohn as a person. By the time he visited the recently completed De La Warr Pavilion, named for the national politician and benefactor who was also the local mayor, he had decided that Mendelsohn was only “friendly to those he thought could be useful to him.”6 Richards does not mention the Architects’ Journal’s exploitation to political ends of the Bexhill competition in his memoirs, and that leads me to think that he felt duped. This story from 1934 to 1935 marks the point from which high-art architecture once more became distinct from the great body of buildings; furthermore, it also sees the start of the process by which interior design magazines set off on an entirely independent path, to the extent that they have now become happily and ludicrously ignored by architecture critics the world over.

Show trials

Hugh Casson, naively mentioned earlier by my 18-year-old self, was seen at that time in the late 1970s as a figure of particular ridicule. His popular image was derived from his success as Director of Architecture at the Festival of Britain, the high-water mark of the Scandinavianists—that is, the British architects who designed in the style, sometimes then called “Contemporary,” that was adapted from the Swedish and Danish architecture of the 1940s as it appeared in the otherwise thin Architectural Review of the period, or as they saw it on subsequent pilgrimages to Stockholm, Gothenburg, Copenhagen, and Århus.7 It was Casson who for a while thereafter enjoyed the privilege of recommending architects for prestigious public commissions. He was a friend and consultant to the royal family; he was an establishment figure, as President of the Royal Academy of Arts, as well as being, like Richards, a long-serving member (1960–1983) of the Royal Fine Arts Commission; and his name was associated with schemes that were actually mainly designed or executed by other people, for example his partner Neville Conder, or, to his greater disadvantage, with clumsy buildings by other architects who had at some stage received advice from him: my local town hall in Margate, actually by the otherwise unknown Fewster & Partners, is one of these.8 No doubt his “ability to charm people by conversational wit,” as a biographer puts it, annoyed the angry young men even more.9 I once came across Casson in the late 1980s: a tiny figure, sitting on a London bus, writing some notes on a pad shortly after an attack by Charles, Prince of Wales, on modern architecture in the form of his television program “A Vision of Britain” which, among other things, had compared some major modernist buildings in London to a nuclear bunker and an academy for secret policemen, the classicist’s response to the still aggressive face of modernist criticism. Sitting beside my hero on the longitudinal seats by the bottom of the stairs in an old Routemaster bus, and squinting hard, I cautiously cast a glance across at his notepad. “The prince is right in what he is saying, but wrong in the way he says it,” wrote Sir Hugh in his neat italic script. I was appalled that so great a man, who had created through the Festival and its many children a cheerful, bright, optimistic architecture, should be reduced to having to use his powers of diplomacy to respond to so vulgar and silly an attack at all. And what this episode also impressed on me was that being polite, and charming, and conciliatory, as Casson was, simply placed him further in the firing line for a brutal attack, and made it harder for him to respond.

It took about twenty years for attacks on British Scandinavianist architects, from the late 1940s to the late 1960s, to become established to the extent that the modernist, and then the Brutalist-conceptualist, interpretations of architecture became the only ones to appear in narrative accounts of twentieth-century British architecture. Brutalism is considered by some to have been launched with a short, italicized, gnomic comment by Alison Smithson (although attributed in print to Peter Smithson) in the journal Architectural Design in December 1953, accompanying a design for a house in Soho:

It is our intention in this building to have the structure exposed entirely, without internal finishes wherever practicable. The Contractor should aim at a high standard of basic construction, as in a small warehouse.10

This sounds intimidating, almost violent, for the design of a private house, and it suited the aggressive polemical language of the Smithsons, who elsewhere talked of imposing the grit and masculinity they associated with northern working-class housing onto the delicate inhabitants of the south, for no good (or explained) reason. This sort of thing is locker-room intimidation, really; cock-flashing, threatening, as it was no doubt intended to be; and it had an inspiring effect on the young architects who simply found the Scandinavianist architecture of the period dull. That in itself this was not surprising, for the buildings were indeed often dull, and had changed little between the end of the war and the early 1950s; even those with a Scandinavianist disposition would find the aggressive work of upcoming architects such as James Stirling and James Gowan exciting.11 But what is extraordinary is the way in which this absurd minority view, this championing of rawness and grit, with no logic, no evidence, or anything realistic at all behind it to support it, and, most of all, no relationship to how life is actually lived and experienced, managed to root itself into the canons of architectural history produced over the following decades to such an extent that the Scandinavianists fell eventually beneath the stylistic and intellectual radar for most critics. If they were mentioned at all, it was with vehement derision. Kenneth Frampton wrote a chapter on this period in postwar British architecture in his Modern Architecture, still widely read by students; it dismisses the Contemporary style as “popular” before hurrying on to what really interests him. There is nothing here at all on the romantic nature of its arrival as the dream style of wartime fighters and little on the imagery that, through the New Towns and prestigious projects such as Alton East, the Brutalist Alton West’s less appreciated neighbor, set the tone for some ten years in British public housing, right across the country.12 Indeed, the book makes no reference whatsoever to any human quality or sensitivity, or romance, or vision, in any building at all. It then alights on an easy target—Basil Spence, a Scandinavianist at first, a romantic and a stylist and, like Casson, an establishment figure, rather than a theorist or teacher. Modern Architecture gratuitously throws in a reference to the “absolute banality” of Spence’s Coventry cathedral of 1951–1962, by any standards an extraordinarily dismissive remark to make about a complicated and rich project such as this. The most memorable point about the cathedral, the aspect of it that strikes every visitor, is that it was devised as a kind of shrine for the works of artists of one of the richest periods in the British applied arts: Graham Sutherland, Jacob Epstein, John Piper, Patrick Reyntiens, John Hutton, Elisabeth Frink, Ralph Beyer, Geoffrey Clarke, and many others.13 In this way it forms the closest equivalent to the rich interior of a pre-Reformation church that the Church of England has offered since the First World War. So, first of all, the architecture critic was separating the carcass of Spence’s building from what was within it, perhaps because of a horror of getting involved with anything sentimental, in this case embodied by the personal and devotional nature of the objects within. This is surely something that no non-architect visitor would do. It is also inconsistent with critical practice, because it is accepted that earlier high-art interiors, for example of arts and crafts houses, were part of the fundamental concept of the architect who designed them.14 And then secondly, even the form of Spence’s building is disregarded, presumably because neither Spence himself nor any contemporary critic talked about it in conceptual or sculptural terms, or because there is nothing obviously peculiar about it. This too is bizarre, because even a brief look at the zigzag sandstone walls and deep mullioned windows of the cathedral tells an interesting story about how a Scottish architect who was immersed in the traditional architecture of his country, who grew up with the interwar interpretations of it, and who was captivated by Scandinavianism, managed to bring all three to life in a single building in a historic English city completely destroyed by war. In addition, the linking of the ruins of the old building with the new one, the aspect of Spence’s design that probably won him the competition, is a significant statement about how people in Britain wanted to reconnect their picturesque tradition with the desperate ruined state of their cities. These are all big stories, I think, that many people can relate to. And yet what interests Frampton instead is, absurdly, the Smithsons’ unsuccessful Brutalist entry for the Coventry competition, which he described as “mediated Palladianism,” a phrase surely unintelligible to anyone reading it or looking at a representation of the proposal.15 How did the Smithsons work their magic? Alan Powers is putting it diplomatically when he describes them as “the clever but disruptive children of a Modern Movement that thought it had settled down for a conformist middle age, [who] justified their rebellion with a rare innate sense of architecture and a personal manner in which arrogance was combined with a vulnerable kind of directness”: in everyday language, what this means is that in Powers’s judgment, they were gratuitously rude, and much of what they said about architecture was self-evident nonsense.16 In the words of Jonathan Meades, the British critic who makes a point of puncturing the literary pretensions of architects and of seeing buildings the way normal people do, “in the pantheon of Brutalists they come way, way down.”17 And yet look where they are—admired by architects and especially architecture students the world over, the subject of endless books and articles, a tribute to the power of verbal bullying.

Figure 3.2

St. Michael’s Cathedral, Coventry, won in competition by Basil Spence in 1950 and derided by modernist critics for some 30 years afterward. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

The Brutalist architect Denys Lasdun longed for “a terrible battle with architecture,” by which he meant a battle against civility and conformity.18 In the 1970s Charles Jencks was still fighting it: his book Modern Movements in Architecture compared Frederick Gibberd’s Roman Catholic cathedral in Liverpool (a loser-building, because it sits on Edwin Lutyens’s crypt, as we have seen) predictably and unflatteringly to Oscar Niemeyer’s cathedral at Brasília (roughly the same shape, but otherwise unrelated); to Marcel Breuer’s work in general; and, inexplicably, to Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, comparisons which are illogical and unhelpful. Like Frampton he deployed the phrase “people’s detailing”—here characterized by “pitched roofs, bricky materials, ticky-tacky, cute lattice work, little nooks and crannies, picturesque profiles”—in a sarcastic way to describe the friendly and thoughtful elements of domestic design employed by the architects of Alton East, and as if there were no difference between these and the genuinely tacky detailing of much artless modern private housing.19 Here again, then, sentiment was sought out and blasted by ridicule. This is how losers are identified and eliminated: through show trials based on unfair and irrelevant comparisons. “Flimsy . . . Effeminate”: in 1976 Reyner Banham, champion of “The New Brutalism,” quoted with relish these words written twenty-five years beforehand by Lionel Brett; they had been intended by their original author to convey bemused appreciation of the Scandinavianist, funfair architecture of the Festival of Britain, but they were deployed by Banham to highlight what looked to him then like a derivative overrated mishmash, a worn-out, feeble, populist style; only the landscaping was any good, he said, and only he had noticed it: a bizarre show-off comment typical of Brutalist dismissiveness.20

In the case of the late Jan Kaplický of the architectural practice Future Systems, architects and writers seemed to pile in on top of each other to be rude about his work, in the letters columns of magazines as well as in critical articles. The Architectural Review, which during Peter Davey’s editorship firmly disapproved of gratuitous formalism, described Kaplický’s Selfridges store in Birmingham as an “outrage” and a “a blue blancmange with chickenpox,” but this was mild compared to a comment from an architect and former Royal Institute of British Architects Council member who, according to the Architects’ Journal, called for the council to “pull [Selfridges] down and start again” because it appeared to contravene a natural lighting regulation.21 For one architect to call for the demolition of the work of another because of a relatively minor technical problem is rudeness at its worst. The critic Kieran Long, writing in a magazine called Icon, which sees itself as a fashion leader, deployed metropolitan sneering: Kaplický’s building was a “blob, a strange juxtaposition of supposedly cutting-edge architecture and marketing that already looks dreadfully out of date.”22 Building Design chose to report two years later that even the head of retail development at the rival department store John Lewis—a company that has prided itself for generations on its friendly image—managed to throw in an insult at Selfridges’ “theatricality” and its dubious approach to “sustainability.”23 Kaplický’s battle to realize his project for a new national library in Prague may have contributed to his premature death in 2009: in an obituary notice, Damian Arnold wrote that “the strain of fighting for the project is said to have taken its toll.”24 It is possible that bullying or humiliation also goes on within architects’ offices in ways that the principals are not necessarily even aware of. Some people have a horror of being asked to participate in physical activities—ones which for example require them to wear shorts in front of the people they work with in order to play sports with them, or to otherwise demonstrate physical stamina or competitive instincts which they might not have. The opportunity to get down on a mat and engage with colleagues in a bout of judo, once offered by Edward Cullinan’s office, might not have been every architect’s idea of practice.25

No one is any wiser about any kind of architecture as a result of writing and speaking about it in aggressive tones; defenses close in, sides are taken, and the great majority of new architecture fails to develop in an interesting way because the publications that architects and their teachers read have no real means of speaking about it and describing it. Some architecture critics invent fake emotions, perhaps evoking some tragic grandeur in a coarse, overscaled building, because they are unable to confront the real, human ones involved. We are all aware, all too often, that a building apparently needs to break some visual barrier or perpetrate an aesthetic outrage of some kind to be worthy of attention. When a building does none of these things—and that is to say, in fact, nearly all of them—architecture critics are reduced either to writing dry descriptions or to talking about vague ideas that are supposedly lodged in the heads of designers.26 In a recent interview with Chris Foges, the editor of Architecture Today, Meades berated architecture critics for their old-fashioned, narrow way of writing about buildings:

A lot of architectural writing, particularly in the broadsheets, takes buildings as stand-alone events, staged by David Chipperfield or Milords Foster or Rogers, and treats them as art objects; it has nothing to do with anyone’s experience.27

Why?

Virile / flimsy and effeminate

Virility: this was the word used approvingly by the Architects’ Journal to describe Mendelsohn’s Bexhill Pavilion as compared to the shortlisted entries for the contemporary new town hall for the London borough of Hackney, all of which were neoclassical. The search for virility has blighted architectural criticism. Why should anyone want it here? Is there any connection with making children? With showing off in the gym? What is its role and purpose in the design of buildings?

Architecture makes plenty of valid appearances in the worlds of the flimsy, the effeminate, and the sentimental, created by other types of artist; the way in which it is treated there tells us something about what is missing from conventional criticism. While Le Corbusier was busy praising the virility of engineers, a novelist who lived in seclusion in the Lake District was writing bestselling books which provide a window onto how architecture was seen by people who were not architects—and indeed no doubt also by some loser-architects who were mired in that great vice of “sentimentality.” From 1930 Hugh Walpole, a popular writer, speaker, and raconteur who is almost completely forgotten now, wrote a sequence of novels collectively entitled Rogue Herries, after the first book of the series, which follow the lives of members of a rural family across centuries of English history. The parts of this that interest me are Walpole’s descriptions of life and architecture from the reign of Queen Anne which appear in the first novel, both because they reflect a current trend in fashionable design—and a victim of the brutality of the virile critics—but also because they continue a notable theme that had been appearing in literature elsewhere.

Before taking this further, we need to look into the connotations of the words “Queen Anne.” They have a particular power to them in architecture, like that accorded to “Victorian,” but more sophisticated in meaning than the latter. The real domestic architecture of Queen Anne, who reigned from 1702 to 1714, was for the greater part not truly distinguishable from the late Stuart architecture that preceded it and the Georgian architecture that immediately followed it—at its best, you can identify it by good-quality brickwork, a relatively large proportion of wall to window, deep timber eaves, exposed sash-window counterweight boxes, and ornamental doorcases. The building of St. Paul’s Cathedral continued throughout the queen’s reign, and some of Christopher Wren’s other monuments, Nicholas Hawksmoor’s London churches, and the great houses of John Vanbrugh are the buildings that lend the period true distinction. When “Queen Anne” was adopted as the name of a style in the latter part of the nineteenth century, the houses described as such did not really match the real thing from a century and a half earlier. The first “Queen Anne” house of the Victorian period is often said to be that erected in Kensington by the novelist W. M. Thackeray, the author of Vanity Fair and much else, apparently to his own design with the help of the architect Frederick Hering in 1860. It looked like an attempt at a Wren style, possibly as a result of the insistence of the Crown Commissioners (who owned the site) on a building that would complement Wren’s Kensington Palace opposite; but it suited Thackeray too, because he was an enthusiast for the eighteenth century, which he popularized through his novels.28 George Gilbert Scott junior—who lived in a genuine Queen Anne house in Hampstead, and was once photographed dressed in a Queen Anne-period outfit—seems to have expressed his defiance toward his father’s strictly Gothic practice by taking up the style some ten years later. This younger Scott, an “architects’ architect,” was widely admired by contemporaries, and others followed his lead. In particular the young stars of the arts and crafts movement who had emerged from the office of Richard Norman Shaw began to experiment with loose and unhistorical compositions of sliding sash windows and brick ornament, the latter often in carved panels, expensive, delicate work; the interiors included much polished, rather than varnished, timber, and ornaments in ceramics and plain metals. The results did not much resemble the far stiffer buildings of the period of the real Queen Anne, but the name stuck. By the time “Queen Anne” emerged as a label in the United States, it referred to a distant cousin of the English versions: it means the ahistorical end-of-century style characterized by ornamental, usually curved timberwork; tiles, colored glass and fancy fireplaces, the predecessor of the Shingle Style. Mark Girouard’s book Sweetness and Light summarizes what the late-Victorian “Queen Anne” was about: it was a reaction to the heaviness of high-Victorian architecture and interior design, and its arrival coincided with a fashion for Georgiana in the drawings of Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway—children’s illustrators, of course. Girouard also points out that the initial professional reaction to the new “Queen Anne” was one of virulent derision, but that the public generally liked it, evidently a rare example of an avant-garde, artistic style of architecture pleasing the latter before the former; and by the end of the century the style had acquired something of the warm, friendly character of the Tudor and Elizabethan revivals that had followed Walter Scott.29

But whereas the Tudor and Elizabethan revivals had been blasted to bits by the Gothic Revival, “Queen Anne” made a sideways move once the high-art people had become bored with it. By the beginning of the twentieth century it was turning into a delicate hybrid style that mixed the early-eighteenth-century with details chosen from the Regency domestic architecture of about a century later: bow windows, tripartite vertical sliding sash windows, ornamental wrought iron work. The appearance of this phenomenon coincides with a revival in interest in the same period by writers and artists. J. M. Barrie, for example, wrote in 1901 a popular and successful play called Quality Street about a genteel young lady called Miss Phoebe Throssell going about her business—card games, shopping trips, exciting young men—in a country town. Lutyens designed the original stage sets for it, and a 1913 book edition featured charming drawings by Hugh Thomson, an illustrator who had taken over where Caldecott left off. In fact the phenomenon as a whole might be called “Quality Street”—a wistful yearning for an age of delicate architecture that had been exterminated by the High Gothic Revival, with its moral strictures and material vulgarity.

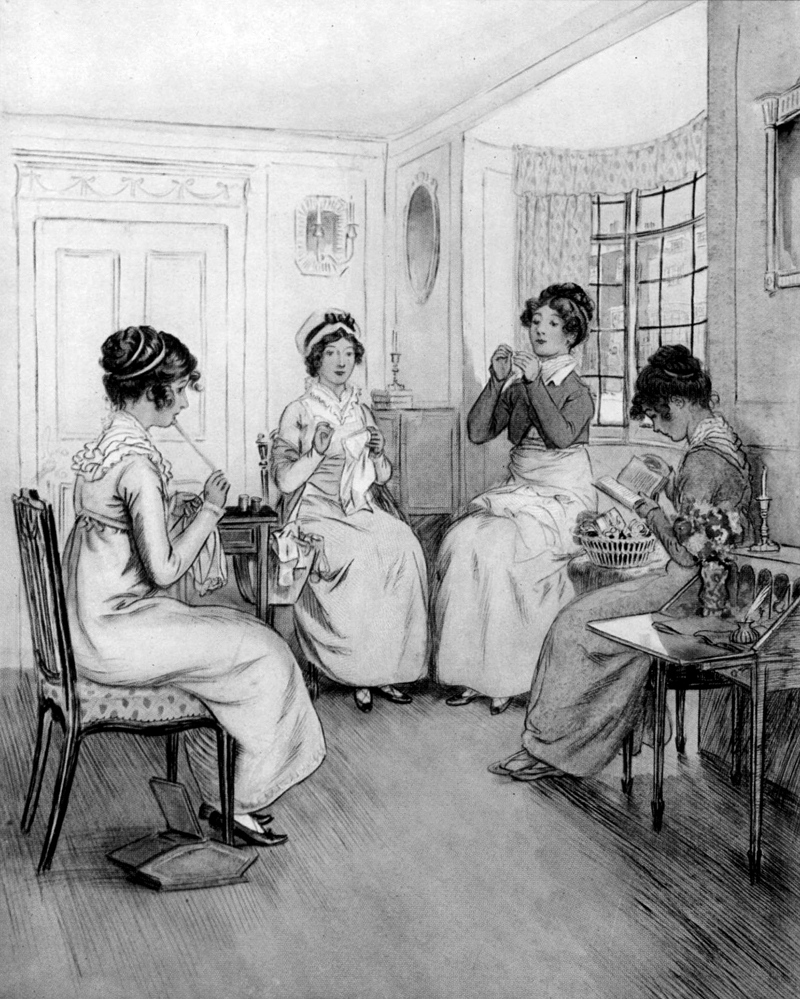

Figure 3.3

“Miss Fanny is reading aloud from a library book while the others sew or knit.” One of Hugh Thomson’s illustrations for a 1913 edition of J. M. Barrie’s Quality Street.

Figure 3.4

The Quality Street style combined early-eighteenth-century forms with Regency-era detailing. This is the “sedan-chair” back door at Horace Field’s Church Times office block in London (1904). Courtesy of the author.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, our loser Horace Field was for a period a Quality Street architect par excellence. The large newspaper and publisher’s building he designed off London’s Kingsway even has a sedan chair entrance round the back. At the other end of the scale, he made the most of wartime restrictions on new building in 1916 by remodeling a row of plain Victorian shops in the town of Farnham in Surrey into an idealized Quality Street-type shopping parade, actually camouflage for a new branch of Lloyds Bank; he placed an unexpected row of Tuscan pillars inside, and one can almost see Barrie’s Miss Phoebe chatting to a matron or a subaltern alongside them. A well-known polemical book of 1928 by Clough Williams-Ellis called England and the Octopus, a condemnation of post-First World War urban sprawl, illustrated the shop fronts as an example of what a town center parade should look like, but failed to give Field, by then in terminal professional decline, any credit for it, another way in which Field found himself a loser; and yet presumably Williams-Ellis had realized that these were not genuinely old façades.30

This was effeminate architecture; and over the years that followed it made friends with an increasingly homoerotic strain in English literature. At first the new hybrid version of “Queen Anne” simply meant calmness, retiral, serenity. That is how it appears when the novelist H. G. Wells deploys it, for example in his novels Kipps of 1905 and The History of Mr Polly of five years later, in both cases making a reference to the picturesque town of Rye in Sussex. In 1925 Field built one of his unsophisticated neo-Georgian houses here, cheap and plain compared to the work of his prime, a kind of empty dolls’ house, for two sisters who, according to their biographer, loved “beautiful places, beautiful things in simplicity and good order.”31 He also converted Chatwin’s ugly bank branch in the town center into a masterpiece of the style, and received the plaudits of the council for doing so.32 The town was a kind of national capital for Quality Street—for evidence you need only look at all the good-taste memorials to Hampstead artists in its parish church. It is not surprising, therefore, that Rye became the setting for E. F. Benson’s extremely camp Mapp and Lucia stories, comedies about two bossy middle-class women with social and artistic pretensions who are surrounded by emasculated, infantilized, probably homosexual men, and are full of praise for “Queen Anne”: “What a wonderful time, Pope and Addison! So civilized, so cultivated!”33

Figure 3.5

Quality Street-style shop fronts added in 1916 by Horace Field to plain Victorian buildings in the Surrey town of Farnham. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

I would say that Field was this time actually in the vanguard of a new movement that was to continue through to the 1950s rather than being, as first appears retrospectively after years of modernist history writing, a failure stuck in an old one. For the fascinating thing is that it was exactly at this moment that the hybrid-“Queen Anne” style suddenly took off in popular English culture, and remained there in some places right until after the Second World War. As the architect Paul Paget put it, looking back at the mid-1920s from his retirement, “to be classy—to be intelligent—you had to like Georgian and that was that”; he was referring to young architects from his own social circle, upper- and upper-middle-class, sociable, cocktail-party, formal-dinner people, the classiest of whom was Gerald Wellesley, the bisexual future 7th Duke of Wellington.34 Books over the last thirty years, usually emanating from the stalwarts of the architectural amenity societies, or of the Royal Institute of British Architects collection, are finally beginning to build up a more representative picture of this type of architecture, but it has otherwise been completely ignored in conventional pan-century narratives.35 The evidence for the rise of “Queen Anne” at this time can be seen all over the place—in architecture, in the wholesale adoption of Field’s style for thousands of bank branches, post offices, tea rooms (especially), dress shops, and much else across the country; in theater and set design, and period films such as Me and Marlborough (1935); in home décor; and of course in popular novels, and in a range of confectionery called “Quality Street” which until recently came in gift boxes and tins decorated with Regency characters, and at one point was sold from a “Queen Anne”-style shop in the center of York.36

One of the places this tendency lasted a long time, and from a late start, has been in the popular series of Superquick cardboard models of houses that train enthusiasts, usually retired and male, still use to decorate their train sets. These were designed from 1960 onward by a commercial artist called Donovan Lloyd in what the current proprietors of the company informally call the “Basingstoke 1935” style, meaning that they are intended to reflect the comfortable high street of the interwar period in the prosperous areas around London; they include, for example, a group called “Regency House and Shops.” The models are still in production, and Lloyd’s attempts to modernize them by including 1960s-style buildings proved unpopular, specifically among the people from the tidy, obsessive, and yet romantic world of the miniature railway modelers who themselves are still longing for the age of the steam locomotive that they can now only just remember.37 Something in the Quality Street style evidently struck a chord in many people beyond the architectural profession. Another place where it made an appearance, in the early 1950s, was in the volumes of the Daily Mail’s popular Ideal Home Book, annuals which accompanied the newspaper’s Ideal Home Exhibition in London, which for a period around the queen’s coronation in 1953 were full of “Regency” wallpapers, furniture, and knickknacks.

Figure 3.6

Cardboard “Regency” façade kits for railway modelers, designed by Donovan Lloyd for Superquick in the 1960s. By kind permission of Superquick Models (PEMS Butler Ltd.).

It must surely be its unreal delicacy that made the style all the more attractive in the interwar age with its morbid fears, or in the postwar era when so much was uncertain, or unrecognizable, or in ruins. It seems logical that architects of these tumultuous periods should want to cling on to the Regency as they might want to cling on to a disappearing childhood, knowing, likewise, that this had been a style that was fated to die. The ultimate illustration of the period for me is James Durden’s Summer in Cumberland (1925), in which a boy in cricket whites stands outside a Queen Anneian Palladian window, looking in as his mother and sister sit at a table laid with a white cloth and a silver tea service.38 Here one feels on one’s skin the dappled light, the buttery glow of the painted room, the distant view of the hills, the flutter of the cut flowers within and the trees without. The significance for me is that the artist has perpetuated a scene which, while perfect, is transient, will come apart and never come back, more so than is the case in most genre painting. This boy, as a painted figure, will never reach his sex-hungry twenties; this mother will never grow old and frail; this sister will never be sold to a loveless husband. The attraction is that transience, that fleeting grasp at something beautiful, something that is gone, something which belonged to someone else anyway. It is the only picture I have ever wanted to be in. If a number of people, the satirist and cartoonist Osbert Lancaster among them, thought of the revived Regency style as a kind of reboot from where architecture had arrived at before the Gothic Revival savaged it, it must surely for others have been a style of failure, one whose future annihilation was perpetually awaiting it in the wings.39

Figure 3.7

Summer in Cumberland, by James Durden (1925). Courtesy of Manchester City Galleries.

This is where the novelist Hugh Walpole comes in. It is easy to see why the Herries novels were such a hit: it happens surprisingly often in them that people are spanking or splashing each other, or stripping off their own clothes or other people’s, usually in or near the Herries family’s rugged rural retreat in the wilds of the Lake District. A great deal of the story’s popular appeal lay, no doubt, in the continued and manipulative contrast Walpole drew between this and the other aesthetic experience of the novels, the pleasant architecture and life of the genteel people whom Herries encounters—for Walpole had latched onto Queen Anne as a form of shorthand for gentility and elegance, everything that rough Herries world was not. A typical example runs:

This modern world so novel, strident, ill-fitting. . . . And (here his Herries blood drove him) he disliked and distrusted this modernity. Queen Anne’s age appeared to him as something infinitely quiet, cosy, picturesque and easy.40

Elsewhere, an affectionate old bachelor uncle who loves the opera, and “has a way with young men,” is described as “an old dreamer and babbles of Queen Anne,” and there is also an architect who “spoke in a shrill piping voice, and trembled with anger, so they said, at the sight of a woman.”41

There cannot be anything realistic here. I may be wrong, but I do not think a Lakeland farmer in the mid-eighteenth century would have fantasized about a style of décor from thirty years beforehand, and so it seems that the novelist is conveying something else, most likely about himself and the times he is living in. Rogue Herries is not a subtle book, and the use of Queen Anne is explicit. It is presented as the architectural style of those who have retired from the aggressive masculinity and morbidity of real life, in the mid-eighteenth century as much as in 1930, and used to give a more explicitly homoerotic character to the earthy parts of the story through simple contrasts: spanking boys in the fields; sipping tea in Queen Anne parlors.42 This is a specifically gay escapism, with considerably more emphasis on the men, undisciplined, unruly, and the boys, their bodies and their actions, than on the women, all of whom are less well developed as characters. The story of Walpole’s own life would seem to make this a plausible reading.43 What I am saying here is that this popular novel, which does not appear to be about architecture, in fact has a great deal to say about it through the few lines dedicated to it within its pages: the descriptions of the Queen Anne style are relatively well developed and consistent in relation to other descriptive sections, and integral to the plot in the sense that one needs to understand these houses and interiors in order to gauge the character of their inhabitants, or what passes through the minds of those who visit there. The period décor in Rogue Herries, and in the films and interior design magazines of the era, are explicit examples of a phenomenon across the 1920s and 1930s in which unconventional people are trying to re-create for a new and unsettled period in their lives the type of interior décor they would like to have had in the first place, in the dream version of their own youth or childhood: the architecture of self-infantilization and retrenchment. If you were Walpole, born in the 1880s—the son of a churchman in New Zealand—you would have grown up with an entirely different sort of interior from those he depicted in his novels. If Alan Hollinghurst presents the architectural significance of “Two Acres” through sensitive, arch hints, then Walpole, addressing a much more general and larger audience, presents his slightly more coherent pictures of imaginary houses as provocative and almost defiant in relation to the norms of his times, explaining without the pretension and elevated tools of an architecture critic exactly how and why buildings are important to a story. In fact it seems to me that Walpole described the appeal of Queen Anne houses rather better than any of the architectural writers at the time managed to do.

This is a book for sissies, then, and it deploys Queen Anne architecture because that was the architecture of sissies—not of the polemicists; not of the Bauhaus or of Le Corbusier; not even of the Architects’ Journal (after 1935, at least); it is the architecture of amateurism, of sentimentality. It is a kind of architecture where discussion is genteel and quite unrelated to concepts. It is reassuring, warm; cozy; well-polished, predictable. As is often the case with gay phenomena in culture, it rapidly spread: The architectural magazines were full of it; even the cover of the Architectural Review with its elegant captions that resembled eighteenth-century script was part of it, evidence that it had considerable allure for the high-art people too. Yet British architectural history has nothing to say about the entire phenomenon of Quality Street and still very little to say about the Regency revival, even if American history, being by and large more catholic, more generous, and perhaps less homophobic, has a little more.

A couple of sissie architects

It is now possible to reconstruct a great deal about interwar neo-Georgian architecture both from the copious literature of the period—books by capable designers about what they saw as good design for shops and shop fronts—and from recent scholarship in journals such as that of the Twentieth Century Society, the British amenity group. But none of these attempts to give any interpretation of the style beyond description, and buildings are by and large characterized in terms of being “good” or “indifferent” examples. Looking at some of these specifically architectural stories differently can indicate how much is being missed. A good example is that of the British partnership of Seely and Paget. They produced one masterpiece and a large number of other buildings for prestigious institutions, including churches for the diocese of London during the period after the Second World War when they were the diocesan architects and surveyors to the fabric of St. Paul’s Cathedral; but to date there is nothing that tells their story as a whole, probably because their buildings were relentlessly indifferent compared to those that we all remember from the period.

John Seely, the son of a politician whose later career was blighted by his having been an appeaser and an apologist for Hitler, took a degree in architecture at Cambridge from 1919 to 1922 and was the partnership’s designer; Paul Paget, on the other hand, had no design training at all, nor any ability to design. He met Seely when they were both undergraduates at Trinity College, Cambridge, and quickly formed a deep bond—“we became virtually one person,” as he put it—and the two established their practice in a pretty and genuine Queen Anne house and street (circa 1705) in Westminster immediately after Seely’s graduation. They lived and worked together until death separated them, and friends and family called them “The Partners.”44 Paget’s job was to run the office and answer the telephone, and he charmed clients and potential clients. In the words of his stepson, he liked everything about being an architect—attending their clubs, openings, parties and exhibitions, and handling models, and so on—except the actual process of design, in which he took no part.45 And no doubt the parties and the rest of it were agreeable events, because both Seely and Paget were well connected through their families to influential people and institutions which quickly provided them with a great deal of work. Their first project involved some remodeling for the well-known actress Gladys Cooper at her house in Highgate, north London, and soon afterward there followed a similar job next door for the future novelist and playwright J. B. Priestley—who, incidentally, was in 1948 to publish a beautiful little piece of late Quality Street drama, The High Toby, with set and costume designs by Doris Zinkeisen, for Pollock’s Toy Theatres. “I mean you were just introduced to the right people, behaved in the right way, and so commission followed commission,” as Paget much later recalled to Clive Aslet.46 The one feature of their architecture which has passed into legend is the double bathroom—two tubs, side by side—at their own pre-Great-Fire timber house at 41 Cloth Fair in the City of London. They subsequently bought and refurbished several other houses in the same street, apparently with the intention of maintaining an idealized streetscape, and after the Second World War they restored the bomb-damaged Charterhouse nearby. They also designed and built a summer house for themselves on the Isle of Wight estate of the Seely family; here they sat and drank cocoa in the evening, and slept one above the other in bunk beds.47

Their one masterpiece is their restoration and new building in 1933–1936 at Eltham Palace, a splendid fifteenth-century hall to the southeast of London which had fallen into disrepair. The additions, for the wealthy Courtauld textile family, turned the hall into the centerpiece of a mansion in an unusual (for England) domestic, brown-brick version of the early French château style, stage-set Henri Quatre. It is the inside, however, that is not only celebrated but seen more often than one might think; it includes a triangular hall which makes frequent appearances in television and film dramas set in the 1930s, immediately recognizable by the marquetry panels depicting Rome and Stockholm around its walls, which recall Williams-Ellis’s remark: “unless you are really rich, it is wise to be born an Italian or a Scandinavian.”48 This interior of this room was designed by the Swedish designer Rolf Engströmer, and the imposing Art Deco-classical dining room by Peter Malacrida; the “Italian Drawing Room,” also by Malacrida, was a showpiece of the style that was dubbed by Lancaster “Curzon Street Baroque,” a style employing pieces of ornamental ironwork from Spanish churches that were then to be found in the antique shops of London’s Mayfair.49

Seely and Paget never again pulled off so comprehensive and successful a building as they did at Eltham, and even then their triumph was shared with the interior designers. The building’s fame is mostly due in any case to its interiors; the outside was described by one writer as resembling “an admirably designed but unfortunately sited cigarette factory.”50 When they worked on historical buildings—for example, during postwar restorations of damaged structures around Westminster Abbey, Eton College, and the ancient King’s School, Canterbury—they designed in a simplified, cheapened version of the style of the original buildings, often (in reconstruction) a weak “Queen Anne.” Many of their postwar churches were simple brick boxes. One of them, St. Mary’s West Kensington, London, sits at the end of the street I grew up in, and I remember it only as a pleasant but plain structure with a slightly decorative tower and pinnacle. I get the feeling, looking now at photographs of the work of Seely and Paget, that they liked sticking slightly decorative things onto or around a plain building; some of these decorative things took the form of an overbold and unattractive overscaled expressed structural frame. Near Holborn Circus, at the boundary of the City of London, they produced a building like this when they restored a damaged church, with peculiar and unsatisfactory results, although they made more of a success of the same idea when they designed the parish church for the first New Town of Stevenage.51

Figure 3.8

Eltham Palace, in south London, designed by Seely and Paget in 1933–1936: the highlight of their career. Courtesy of English Heritage Photo Library.

One of the interesting facts about Seely and Paget is that they built up a substantial practice and reputation through working in no definable style, rather in the way that some celebrities seem to make a career out of being celebrities. It is quite possible to be a good architect in a challenging and austere period using an indefinable style of bricks and concrete frames: George Pace, a church architect a little younger than Seely and Paget, was just that, bringing traces of Gio Ponti to provincial England. But neither the trained Seely nor the untrained Paget had any talent for designing. When Seely died, at the comparatively early age of 61, Paget had the grace to resign the surveyorship of St. Paul’s Cathedral, knowing that he was not capable of doing it on his own. He finally troubled himself to travel to Italy for the first time, and then retired to Templewood, the camp, beautiful little pavilion the partnership had built in Norfolk for his uncle in 1938 which incorporated parts from two recently demolished major neoclassical buildings, Nuthall Temple and the Bank of England. Paget decorated its single large splendid room with a ceiling mural in Tiepolo style by Brian Thomas which depicts glorified versions of his young self, for example posing as a schoolboy athlete, although in reality he had always been hopeless at sports. There is a vast number of documents and drawings from the partnership in the collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, but it seems unlikely that anyone will want to spend the time required going through it all. If it were moved into a library for the studies of masculinity and gender there might be a better chance of that, because the story of Seely and Paget is primarily one of a strong partnership between two teenagers who wanted to grow up together and do things together. This is what the story is about, I think, and how this played a role in mid-twentieth-century modern life. Paget waited for eight years after Seely’s death before marrying for the first time at the age of seventy. Seely and Paget were the sissie architects about whom no conventional architectural historian has so far thought of anything to say.

Some architects form groups that seem to have been bonded together by homosexuality, and in some cases by failure too. Clive Aslet, one of the few writers whose work evokes the full story of the buildings he discusses, says that everything to do with the homosexual Charles Ashbee and his various endeavors was marked by failure, from his attempts at founding a living-working artists’ community (with nude river bathing, music playing, hopeless economics, and so on) in the Cotswolds, to his work for the doomed Earl Beauchamp at Madresfield, the latter a clear example of a house haunted by what he calls “the suggestion of failure and even tragedy that befell so many Arts and Crafts undertakings.”52 I wonder whether homosexuals who did much of the work for major architects were particularly prone to loserdom—possibly for example Joseph Wells, the first principal designer of McKim, Mead and White; and some of the ghost designers for Philip Johnson’s practice, or in his circle: John Bedenkapp and Peter van der Meulen Smith, for example.53 It is not surprising that the bullies can identify the sissies who may in some cases be in explicitly homosexual groups, and then set out to crush them. Of course, some well-known homosexual architects have themselves been quite good at bullying; but surely for much of the twentieth century most were bullied and lonely people, and their response to their condition may have been to try to design themselves into a more beautiful world: that is, a sentimental one. In the interwar period that tendency may have been further exaggerated by a more general “morbid” response—to use the historian Richard Overy’s word—to the apparently catastrophic condition of Europe and America, and the ugliness and squalor of the cities and the poor that must have seemed beyond redemption.54 And in England, in any case, it was until recently by no means unusual for any people with an interest in the arts to be treated as if they were homosexuals. As Bryan Appleyard put it in his biography of the unmistakably heterosexual Richard Rogers, already living and sleeping with his girlfriend at the age of fourteen, his school’s

hearty, healthy brew of sport, hard work and bracing spirituality broadly categorized the sort of artistic sensitivity that Rogers was absorbing from Dada [his father] as something to do with homosexuality.55

The “beautie of holinesse”

As a group, evangelical Christians are capable of an almost unsurpassed bullying of homosexuals and sissies in general; and evangelical attitudes to church architecture and interiors are likewise bullying to an extent that goes beyond threat to actual aggression. Presumably, like Rogers’s teachers, they think that the two are related, and that sensibility to the visual arts marks a person out as being insufficiently manly. This has a long history to it, as the organized destruction of church art at various points in history continuously testifies, from the Reformation to the English Civil War and Commonwealth—and it continues now in England, after an evangelical minister has taken over a church which still has surviving Victorian artifacts in it. The handbook used by evangelicals, described on its cover as “the definitive guide to re-ordering church buildings for worship and mission,” and much reissued, is called Re-pitching the Tent. It was first published in 1996 and written by Richard Giles, a priest with a record of remodeling churches in both Britain and the United States.

Giles’s book tells you how it is done: something called “Victorian clutter” is removed, which means just about everything, and new and cheap furniture is put in its place. Facing the start of a chapter called “Our Mobilisation” there is a full-page illustration of a Gothic church being demolished, while the vandalistic churchgoers hurry joyously to a new, ugly, shedlike building in the distance, rather like one of Pugin’s illustrations in his Contrasts but intended to make the opposite point.56 In fact Giles deploys a Puginian trick when he compares views of Wren’s St. Stephen’s, Walbrook, in the City of London before and after recent reordering: the former is depicted in a dull black-and-white photograph, the latter flatteringly in color.57

Gleeful destruction is all around in Re-pitching the Tent. One story told in the book explains how a congregation recorded the “history” of their building by leaving the scar formed when a Victorian pulpit was removed rather than having the stonework restored.58 That looks to me like sadism. In the United States Giles oversaw, as dean, the reordering of the Episcopal cathedral in Philadelphia, which consisted of the removal of its historical artifacts and murals and the insertion of fewer, cheaper and less long-lasting replacements. This process caused some friction at the time; Roger W. Moss, the historian of Philadelphia’s places of worship, questioned the “wanton destruction” of the building’s earlier rich decorative scheme, and pointed out that other reordered churches had managed a reasonable degree of compromise; he asked whether the Giles scheme was simply “insensitive vandalism sanctimoniously cloaking itself, in the dean’s words, with a ‘conviction that the mission of the Church should always take precedence whenever architectural layout conflicts with the Church’s current needs in liturgy or ministry’,” a bold phrase that stands out in a book otherwise written in notably diplomatic and sympathetic language.59 The new scheme and the terms used to defend it were, to me, an example of architectural bullying, perhaps aimed at aesthetes whose priorities are, quite simply, not important to busy, “virile” people. And bullies are not satisfied with just removing a pew here and there. In 2006 the British government tried to demolish Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners’ beautiful Commonwealth Institute in Kensington, that gorgeous cadmium-blue butterfly I loved so much as a child, which sits on state land, with the argument that starving children in Africa would die unless the site was sold to support the government’s international aid program.60

It always astonishes me that even the waste of good materials does not bother these people. As a member of the Victorian Society committee which considers applications to alter buildings listed for their architectural or historical merit in the south of England, I see time and time again cases where a minister responds angrily to the charge that he is destroying the long-term heritage of his church by telling us that this is what God, or Jesus, wants him to do. God has asked him, for example, to replace a fine oak door on wrought-iron hinges with a glass one so that passersby can look through and be “welcomed” in (these makeshift glass porches are sometimes called “Welcome Doors” on their architects’ drawings); or to smash up or sell “inflexible” Victorian benches, as if God didn’t know any more than the vicar that a glass door will reflect the sunlight outside rather than allowing a view in, or that the churchgoers, having removed their Victorian benches, will not actually bother to rearrange their replacement plastic chairs as one year follows the next. Or that God didn’t know any more than they did that the artifacts of religious culture are also the memorials of those who made them, the only kind of lasting memorial those mainly forgotten people, with their hard lives, are likely to achieve.

A recurring feature of these applications is the provision of lavatories for visitors, inside or directly attached to a historic, even medieval, building, even when it would be perfectly possible and reasonable to allow these to be located at a manageable distance from the old one. It turns out that the prominent and intrusive provision of water closets is an article of faith—literally—for evangelical Anglicans. Following a discussion on one of these applications, I Googled the local vicar, not least because his name was familiar as someone I had shared a staircase with as a university undergraduate, and I found a recording of a sermon he had given in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, in a church at the extreme end of the British ultra-evangelical spectrum. Very soon he launched into this favored aspect of architecture, perhaps the only one that these people find interesting.

The message I understood from the vicar’s address was that it was a matter of principle not to accord the fabric of the church building, however venerable or beautiful, any kind of priority over the practical needs of the congregation. The fact that mainstream or High Church Anglicans do not add lavatories within the aisles or even the naves of their ancient churches, and seem to revere their accumulated historical contents, in particular their “Victorian clutter,” is apparently a sign that they prefer buildings to people. The vicar was valiantly fighting against any suggestion that people and the structures they inhabit or use often share a common narrative—the one thing that is needed for people who are not architects if they are to value and talk about buildings. I would have thought that the insistence on the prominence of an ugly block containing many lavatories at considerable cost to the aesthetics and completeness of a sacred building showed an almost psychotic hatred of beauty, not to mention a nasty tendency to bully both a building and those who valued it. Looking back at Anglican history, it seems clear that the Puritan assault on Archbishop Laud’s attempts at beautifying churches despoiled at the Reformation—the “beautie of holinesse,” as it is sometimes called—was at least as much an act of aesthetic bullying as the political and theological attack it is generally made out to be. And “Victorian clutter” is in any case a subjective and misleading term, deployed as tendentious propaganda. As Tom Ashley, the Churches Conservation Adviser of the Victorian Society, recently put it, when describing the intended despoliation of yet another fine medieval and Victorian church by an evangelical congregation, the neat lines of Victorian benches usually contribute order and repose to a space, whereas the curved rows of moveable chairs preferred by evangelicals, which often cut through the nave and aisles without any reference to the axial rectangularity of their spaces or even of their massive stone piers, are disruptive and disturbing.61 So what ought to be a discussion about architecture, its associations and its stories, its beauties and its dreams, turns into some kind of a sermon about lavatories and chairs. This is what I see time and time again from my membership of the committee: England’s beautiful medieval churches, sometimes restored and furnished by Victorians to what were then the highest standards of design and craftsmanship in the world, continually under threat of vandalization and mutilation by a here-today, gone-tomorrow priest; they are soon filled with cheap tiles, cheap carpets, cheap furniture; cheap everything. It is true that talking to bullies is always difficult, but this situation is the consequence of there being no adequate common language for talking about everyday things in architecture.

Sliding into hopelessness

I am going to stay for a moment longer on the subject of churches, and use it as a bridge between the perpetual losing battle between the bullies and the sissies, and the next chapter, on hopelessness. I am looking now at a rather glum book, recent but with black-and-white photographs, which is a gazetteer of churches built for the Church of England in London between the two world wars. Few churches were in fact built until the 1930s; then the Church experienced one of its short booms in activity, a boom which—like a later and similar one in the 1950s—soon fizzled out.62 A handful of these interwar churches are the work of great designers: they include Edward Maufe’s church of St. Thomas, Hanwell, a masterful sculpted brick composition in the suburbs of London that was evidently considered progressive enough to have made it into the newly modern Architects’ Journal in 1935; Maufe also produced the smaller St. Saviour, Acton; and Giles Gilbert Scott, like Maufe a cathedral designer, built St. Alban, Golders Green, not one of his more memorable designs. These winners’ buildings make only slight reference to a historical style, and their impact as buildings derives from the emphasis their architects placed on the general sculptural form of the buildings and their white walls, good sculpture and brickwork; if anything they are slightly Byzantine in appearance. There are also two good expressionist churches by N. F. Cachemaille-Day, Britain’s unrecognized answer to Fritz Höger and a loser, I think, given the lack of interest in and the physical condition of his churches today; and a gaunt basilica by Adshead & Ramsey, for some reason not in the same neo-Regency style as the architects’ Duchy of Cornwall estate in Kennington nearby. But pretty much all the rest of the buildings are disappointing failures. Some 1920s Gothic buildings are reasonable, if somewhat on the cheap side; some are stretched-out, washed-out Victoriana; some already have a cheapskate feel about them; some were conceived on a grand scale but never finished. Many of the others look like cinemas; there is a characteristic one in Tottenham, north London, by Seely and Paget, that for me still says “the weekend is over,” because I used to pass it in the car when my aunt was driving me back into London on Sunday evening, ready to go off to school the following morning. It is fronted by a semicircular portico which is one of their “decorative things,” here attached to a block that looks as if it ought to be a gymnasium, very peculiar and clumsy (or, in the understated words of the book’s authors, “rather odd”).

Figure 3.9

The Church of St. John the Baptist, Tottenham, north London, by Seely and Paget (1940): more typical of the greater part of their output. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

But the great majority are in no particular style: perhaps they are a little Byzantine, a little Tudorish, or in a cheap or thin Gothic: they could almost provide an updated illustration for the buildings derided in Pugin’s True Principles, or An Apology. Milner & Craze, mainly well known (if at all) for having disappointingly rebuilt Pugin’s St. George’s Cathedral, Southwark, south London, after serious bomb damage in the Second World War, and the awkward, Spanish-looking (almost) High Anglican shrine at Walsingham in flat and cold Norfolk, appear here as the authors of two churches within the same borough: the first in a curious pre-Pugin Gothic style, the second in no style whatsoever. The Gothic Revival, for all its bombast, did manage to establish a common, understandable language for the architecture of churches; the Church of England, in decline after the First World War, found none. Thus these buildings seem to sum up the failed achievements of the era, worth nothing to conventional historians. What this little book provides, then, is a window into an area of hopelessness, a great endeavor to build churches for the established church in the metropolis, which ended up with a collection of buildings of dubious quality, nearly all sissies, buildings to be laughed at for their feebleness of style, all presented through unprepossessing amateur black-and-white photography with little contrast, all of which adds to the sense of futility of the buildings and even, in turn, of the project of looking at them and recording them. I am delighted to say that the authors have now published a successor volume on the new London churches of the postwar period. After all, as all loser and winner architects know, there is nothing like wasting one’s time reading or writing a book when there is something more masculine that is waiting to be designed and built out there somewhere.