Figure 4.1

St. Mark’s Church, Ramsgate, Kent: the Byzantine chancel (1937) is by Thomas Francis Ford, and its economical nave (1967) by Percy Flaxman. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

4 Hopelessness

What is it really about?

This is a chapter about some other ways in which designers can fail to achieve the thing they are dreaming of when they set out to create a building, and about how the hopelessness of a project from the outset and the disappointment with its outcome can turn out to be the most interesting things about it. No doubt many of the churches we heard about in chapter 3, especially the unfinished ones, carry the traces of fascinating stories. For me these buildings represent together the height of aspiration but also the disappointment of their realization, the giving birth by the architect to a malformed child. They can set off a little series of explosions—a chain reaction of one disaster after the next—the more one looks into them, each one carrying, like sad comets, a trail of stories in their wake.

At a road junction a few minutes’ drive from my house there is a small evangelical Anglican church called St. Mark’s, located on a large and mostly empty site. You will doubtless be able to find something similar near you. What originally drew my attention was the tall but narrow block with arched windows, built from red-brown brick, that occupied the center of the complex, designed in a style that might be called interwar Byzantine, and looking pretty much as a part of a church ought to do. Attached to the east and south ends of this structure is a plainer but contemporary wing, which is the church hall, and at the west there is a more recent low, nondescript extension with a short, narrow tower that could be anything. My feeling every time I passed the building was that there is something very sad in the idea that an architect can relate to an ugly suburban area as if it were a corner of a village in Byzantium, just as all those Tudor and “Queen Anne” bank branches and shops of the 1920s are sad because they are in places that could never be transformed into somewhere beautiful. Even if it were possible, it would take many, many decades and similar-minded designers to achieve it, and so even to embark on a project like this is already an admission of a future failure, however much contemporary writers of any period might have talked up the style. You can see something similar every time an architect in Europe or Asia tries to design a building that looks American, or for that matter an American designer tries to build a piece of “Europe” somewhere where it really does not seem to belong.

Figure 4.1

St. Mark’s Church, Ramsgate, Kent: the Byzantine chancel (1937) is by Thomas Francis Ford, and its economical nave (1967) by Percy Flaxman. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

Much worse, however, is the fact that architectural historians know that there was here, in the immediate vicinity, a terrible architectural loss about fifty years ago, and thus the impressive fact that St. Mark’s Church is now the most prominent building in the area is a distinction it simply does not deserve. In a road just behind it sat, until its demolition in the 1960s following war damage and subsequent desuetude, the delicate and beautiful Ramsgate municipal airport terminal, a tiny pavilion that looked like the outspread wings of a biplane, captured for a famous photograph of 1937 by Dell & Wainright. The site of this structure to the northeast of the church is now part of an ugly industrial estate, and is occupied by a shed that houses a removals agency and a wine wholesale distributor—no trace whatsoever of the airport remains. Its designer was David Pleydell-Bouverie, an architect who was until 1934 the partner of Wells Coates in London, but who some years afterward left England for California, in the opinion of his obituarist Humphrey Stone a delayed reaction to his cruel upbringing and the bullying of his authoritarian father.1 On the West Coast he dressed as a cowboy, wore tight jeans, moved into land management, and was married for ten years to Alice Muriel Astor Harding as her fourth husband; the only building he is said to have designed after leaving England was a house for the food writer M. F. K. Fisher.

Figure 4.2

Until its demolition in the 1960s, the most significant building in the immediate vicinity of St. Mark’s was Ramsgate airport, designed by David Pleydell-Bouverie and captured here by Dell & Wainwright. Dell & Wainwright / RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

This much I knew about St. Mark’s and the area around it, but initial research revealed a situation that is more disappointing than I had imagined. The “Byzantine” part of the church was designed in the late 1930s by Thomas Francis Ford, at the time an architect for some ten years of new churches and alterations to them, and the founder of what has since become a major restoration practice.2 His short, tall block turns out to be the chancel only of what was intended to be a large and imposing building, for the church’s website explains that St. Mark’s was to have had a long nave and tower, the completion of which was frustrated by the war. So the western extension—of 1967, by an architect from north London called Percy Flaxman—was an apologetic attempt to complete what was supposed to be a grand building.3 Flaxman surely intended his little tower to compensate for the lack of the grand 1930s one, just as his “arched” (in fact, straight-sided triangular) concrete lintels were presumably supposed to echo or complement the few more expensive Byzantine arches of what was built of Ford’s church.

A lengthy history of the parish that was printed in 1993—the kind of account that records small details from every parish meeting and social event—notes that the original commissioning process was started in 1937 to mark the coronation of King George VI that year but says nothing about the design, or the name of the architect and how he was chosen (a recommendation from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners or diocesan surveyor was the most likely route); it takes no interest in the Byzantine fantasy and fails to record any reaction to it by parishioners.4 There is no record of Ford’s drawings either in the local diocesan collection at Canterbury, or at the Incorporated Church Building Society (ICBS) archive at Lambeth Palace Library, the record center of the Church of England. I then discovered that the vicarage does possess a plan and a perspective view by Ford of a proposal dated May 4, 1937—a week before the king’s coronation—and although this appears to be of the final scheme, the Byzantine element is underplayed. In fact the style of the tower, which was to have been at the southwest corner of the long nave, was actually Romanesque, with a timber belfry, so the fragment that was erected gives the wrong impression altogether.5 Because of the lack of completion, but also because no one among the parishioners is recorded as having found a way of thinking or speaking about it, or recording or publishing their thoughts about it, Ford’s dream building will remain a mystery for most. There is slightly more information about Flaxman’s extension, perhaps because the author of the parish history remembered its construction from first hand, although the ICBS records, without drawings, only Flaxman’s failure to gain an approval, presumably for an earlier scheme, in 1964–1965.6 There is nothing in the new “Pevsner” guide about the church, although the latest editions generally refer even to small suburban churches, and there is nothing either in the catalog of the British Architectural Library (BAL).

Unlike the story behind Ford’s appointment, that of Flaxman’s is related in detail in the parish history, evidently because the congregation found this more interesting than the actual design of any building. The vicar in the early 1960s had a brother who was an architect in Edinburgh called Eric Hall, who proposed to design the building without charge; because of the distance involved this was impractical, and the brother asked a colleague of his, who was Flaxman, to carry out the work.7 Flaxman did this at a reduced fee, and with the assistance of a local architect called David Cox, who died in 2012 and thus cannot be interviewed. The parish history records the following somewhat unenthusiastic observation sometime after the building had been dedicated by the Archbishop of Canterbury in June 1967:

[Flaxman’s] simple and unorthodox building plan effectively fitted the new part to the older, and as time went on it became clearer that there was a great gain in entrusting the whole scheme, including such small but prominent things as the hymnboard, to one mind.8

The hymnboard: this is the only architectural reference in the entire history of the hundred years of the parish and its buildings—something of a testament to the gulf between the dreams of architects and their reception by people who cannot understand them. Indeed, the parish history recorded that it was difficult at first to raise interest in the project at all, and thus funds, even for Flaxman’s cheap nave.9

So the building that has replaced the beautiful, delicate, vulnerable, idealistic butterfly of the Pleydell-Bouverie airport as the major architectural structure of the immediate area is merely this jumble of an unfinished, overambitious building with a cheap extension, the latter of course a victim of its time, a period when to go on building Byzantine or Romanesque would have been unthinkable; Flaxman’s little tower is all the more of a disappointing gesture toward Ford’s church, because it sits in the same place as the grand one on the unexecuted scheme of May 1937. The first architect’s original drawings have disappeared into private ownership: no one had anything to say about them on the record, anyway; and Flaxman’s have vanished without trace. There is here no landscaping, or any kind of imposing forecourt. There is no Byzantine village; no picturesque street corner; no colorful realized vision of an exotic suq; no Norman village either, no hearty yeomen entering by a stocky bell tower; no happy throng of pious, well-dressed people going gladly about their daily business—just an ugly and largely empty street corner, in the suburb of a small provincial town. I mentioned in my introduction that “disappointment” and “failure” were not metaphors but actual descriptions of loser-buildings: here is one of those, in front of our eyes.

And yet it is here that the real story begins. Although it is possible to work out a conventional description of the church’s design and evolution, the evidence suggests that what was built at St. Mark’s might be about something else altogether, and that something comes only in fleeting, contradictory, and highly personal fragments. And whereas the conventional narrative will only ever be about a small and unimportant building that will interest almost no one—not even, it appears, the parishioners themselves—the tale behind it is something that touches on the grand themes of life: dreams in a banal world; the frustrations and hopelessness of being an architect; the tragedy of an inconclusive building. And that real tale lies in the relationship of the architects to their buildings.

In Ford’s case, his application to become a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1932 was accompanied by a list of his works to date, and in the “publications” section he mentions that he was the author of a thesis on seventeenth-century buildings in the Yorkshire town of Halifax, for which he was awarded a distinction. Ford at least left behind him a flourishing architectural practice that still carries his name; the story of Flaxman, however, demonstrates how easy it is for the records of the life and work of an architect, which are sometimes extensive and revealing, to vanish when there is no documentary evidence of them. The catalog of the BAL has nothing on him, so the buildings he designed himself were not picked up as such by the press and will be hard to identify for future researchers. The RIBA membership department had on record only that he had been a student at the Architectural Association during and after the Second World War, and from this information I found him in retirement at Frinton, on the Essex coast, and spoke to him.10

Flaxman’s absence from the BAL catalog was explained by the fact that he had spent his career, as an architect and later as a landscape architect, either working for private practices bearing the names of others—mainly, Troup & Steele, the architects known principally for the Brutalist work at King’s College, London, and the commercial architects The Ronald Fielding Partnership—or for the government, as a specialist conservation architect for the Directorate of Ancient Monuments and Historic Buildings, a forerunner of today’s English Heritage. He had nowhere to store his own collection of architectural drawings when he moved into a smaller home on retirement, so he had destroyed them. I told him that the only Internet reference I had found to him was that he had been employed in mid-1992 as a consultant by Historic Royal Palaces, a government agency, to report on the restoration of the maze in the gardens of Hampton Court Palace.11 In fact, he then told me, he had been originally called out of retirement to carry out work on the Palace itself, as the restorer of the William III-period apartments there following the fire of 1986; with Pamela Lewis he had refitted out the destroyed rooms with wall hangings and curtains, drawing wherever possible from the original detailed specifications of the late seventeenth century—late Stuart, not quite Queen Anne. While still employed by the Directorate he had worked on the restoration of parts of Kensington Palace in London, another Wren building, converting a derelict, still war-damaged part of the site covered by a temporary roof into the apartments to be used by the newly married Prince and Princess of Wales in 1981; furthermore, he added a William IV-style Doric portico, inspired by the early-nineteenth-century architect and writer W. F. Pocock, to the Palace’s north front—a structure invisible to all but Palace residents and their private visitors. There was, Flaxman told me ruefully, very little interest in and money for building in historical styles during the period in which he practiced as a conservation architect. To try to do anything like that, for example for a small church in Ramsgate, would have been intrinsically hopeless.

I found a single reference to Flaxman in print—an article on the design of Danish gardens that he contributed to the Architectural Association Journal in June 1951. This is part of what he had to say about the private garden of Mrs. Erna Friis at Lellinge:

The iris and soft foliage of the broom will bind the design together as the flowering season moves over the garden and the Hostas take deep shadows and bright reflections under the shade tree. Even the smoothness of the lawn merges into the border—“border” is almost the wrong term to use as it suggests something all too formal—by a transitional planting of the creeping Cotula squallida. . . .

The herbaceous planting is the backbone of this garden, but the wide expanse of lawn and mature feature trees are linked with the long low house by a cloudy froth of lavender, gypsophylla, roses and pink lilies. The drawing room invades the garden here; the roses are all shades of pink and the grey of the lavender is carried over the ground with catmint and prostrate thyme. It is superbly effeminate and the pinks and mauves are blended with the white in a billowing softness.12

Deep shadows and bright reflections; the smoothness of the lawn merging into the border; the cloudy froth of lavender and lilies; the billowing softness. An apartment in Kensington for Diana, Princess of Wales, and a new neoclassical porch; tapestries and wall hangings for one of Britain’s great palaces. And yet, if the records are anything to go by, all that this architect has to show for himself is a cheap and disappointing 1960s nave dumped unceremoniously on a stretch of mean grass and an asphalted parking lot on a suburban street corner. If Ford’s head had once been in the early neoclassical period in Yorkshire, was Flaxman a Regency fantasist, dreaming of Bath, of Beau Brummell, of the Prince Regent at Brighton, sashaying into baroque mazes like the architect in the film The Draughtsman’s Contract, or flouncing through effeminate Danish gardens as the cities of England still lay in ruins? Had he been working at any period other than the three decades following the Second World War, would he have been able to realize any of the projects he really had a passion for? These are the things that this church is really about, aren’t they? These and the departing shadow of David Pleydell-Bouverie, bullied, exiled, finally liberated from a miserable English childhood into tight jeans and Californian sun. It is striking that architects, and especially architecture critics, have a soft spot for fantasy architecture of various types, such as unrealized projects by well-known architects and the architecture of science fiction and adventure films, but almost never show any interest in the fantasies of these everyday architects, which are in many ways at least as interesting and rather touching. What an ordinary suburban failure of a building like St. Mark’s tells me above all is that there is likely to be a so-far-unwritten architectural history of some depth and power in every town, a history that can be written in a way that can reach out to people who have difficulties in speaking or writing about buildings. Whether it is about the failed Byzantine or Norman villages, or the fantastic beauty of the Danish garden, and the frustration and hopelessness of trying to realize them on an everyday street corner, there will be something somewhere that means much more to the parishioners of St. Mark’s than a set of drawings for a church and its extension.

No future

There have also been architects who have been asked to build something with a healthy budget but a long way above their capabilities: an example sometimes given of a building that disappoints by its failure to live up to its site and budget is that of the new house at Eaton Hall in Cheshire, designed for the Duke of Westminster in 1971 by John Dennys, erected on the site of Alfred Waterhouse’s superb but unmanageable Gothic mansion which had been demolished eight years earlier except for its chapel and stables.13 To condemn Dennys, as is often done, as having being chosen because he was the brother-in-law of the duchess is unfair, for he had been a teacher for almost a decade at the Architectural Association during the 1950s, and had recently been president of its council; who knows what else he might have achieved, had not his career and life ended in an accident in Greece in 1973 when he was only 51.14 Yet his building looked so hopeless, a clumsy blotch in its travertine marble facing, and so pathetic as the termination to a long avenue, that it was later remodeled and refaced in 1989–1991 by the Percy Thomas Partnership, generally known for their commercial and institutional buildings, and now it resembles a stranded, large and provincial, French department store. The real story of the Duke of Westminster’s new palace is actually thus the story of its sequences of embarrassment and hopelessness.

Just as there were architects like George Basevi who seemed unable to cope with the demands of the new Gothic Revival, there must have been many more who were defeated by the increased technological demands of architecture from the post-First World War period onward. They sank disappointedly into retrenchment as the expectations for technical expertise demanded of a modern architect folded over their heads, or they became distressed by the way in which architecture seemed now to be about something unfamiliar. The phenomenon must have recurred endlessly right across the Western world. The Danish-Israeli architect Ulrik Plesner recalls in his autobiography that his great-uncle, the distinguished architect of much of the resort town of Skagen on Jutland who bore the same name as himself, discovered that he “suddenly belonged to the past. He died puzzled and sad” in 1933.15 The fate of Martin Lovell, the architect hero of a novel called Bricks and Mortar, written by Helen Ashton and published the year before, seems to reflect that of Plesner, but perhaps more specifically of Basevi himself: born in 1868, he is as a young man enthused by arts and crafts design, the style of his first houses, but as he matures he slowly discovers in himself a growing affinity for Queen Anne and then the Regency. He lives in one of the early-eighteenth-century houses in Barton Street in Westminster, where some of Horace Field’s best work, in a romantic version of the same style, would have been visible from his front door. The vulgar Edwardian baroque of the new shops and offices that have replaced Nash’s Regent Street disgusts him.16 At the end of the novel he visits the site of a modernistic building in London designed by his son-in-law Oliver, who has recently returned from New York full of enthusiasm for its jazzy tall buildings. Martin is puzzled by Oliver’s building, with its dirty gray concrete frame and its inexplicable proportion of glass to wall; he climbs up the scaffolding, to catch a glimpse of the Wren churches he so enjoyed, and while he is up there, he falls from the ladder to his death. The novel ends immediately. There was, evidently, nowhere left for him to go.

I have mentioned that the striking thing about Quality Street and other hybrid Regency or Georgian revivals is that those who promoted them already knew that historically these were doomed styles; and we know now that the people who enjoyed them most in the 1920s and 1930s were aesthetes. They remembered that the Gothic Revival had finished off this whimsical, lightweight neoclassical architecture, so well suited, in their own times, to tea rooms and Bond Street shoe shops: in fact one clear achievement of the Quality Street style is that it actually could bring a touch of Bond Street to every town center parade. Is there, I wonder, a death wish involved with this revival, a pushing of one’s own head under the waves? One of Field’s least effective projects was to try to give an elegant Regency face to the austere, aggressive Gothic of Edward Pugin’s Granville Hotel in Ramsgate. He added a veranda topped by a little white timber pediment to the front, decorated with his characteristic bold dentils; he affixed Quality Street-style wrought-iron railings to the façades; and he reduced the height of the building’s monstrous tower, shaving off the outer planes of its projecting oriel windows which ever since have looked like the victims of a botched medical intervention. In the perspective of his scheme that was published in the Architect on November 2, 1900, the remodeled building is depicted as a cheerful place, with plenty of greenery writhing around its many balconies in an unconvincing attempt to smother some of its ineradicable Gothicness. But the jolly bandstand and the contented holiday crowds fool nobody. It was a hopeless assignment; it could not have been done well by anyone.

Figure 4.3

Horace Field’s additions and alterations to Edward Pugin’s Granville Hotel, Ramsgate, in 1900 included the addition of a Quality Street veranda in white timber and the mutilation of its tower. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

Now Edward Pugin is famous again, and Field is not, so Field clocks up a further failure as the mutilator of a “better” building by somebody else. But Field at least was a good designer at the time. Being a second- or third-rate architect, and having as part of your record the mutilation of a fine building by someone better, is a true hallmark of loserdom. The website of Pembroke College, Cambridge, records the names of some of the great designers who contributed to its architecture: Wren (the college chapel in its original form was his first completed work); Alfred Waterhouse; George Gilbert Scott junior; W. D. Caröe; Eric Parry.17 The list does not include Maurice Webb, the eldest and not particularly talented son of the successful and well-regarded architect Aston Webb, in the late Victorian and Edwardian era the designer of significant London monuments such as the main block of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the processional route from Trafalgar Square to Buckingham Palace, including the Victoria Monument and the front face of the palace itself. Webb junior, who took over the running of his father’s practice in the early 1920s, was a graduate of Pembroke. He mutilated Waterhouse’s high-Gothic dining hall in 1926 by lowering the ceiling and adding fatuous, uncomfortable, Quality Street features; and in 1933 he designed a new master’s lodge in the style of a characterless, flat-faced dolls’ house where I once was refused admission to join my parents for lunch by the then master, a building which anyhow has now vanished under a much-praised building by Parry.

Webb has other strong claims to hopelessness. He died aged only 59, just before the Second World War; and traces of him are being eradicated from other places too. His most successful building was a department store (1931–1935) called Bentalls in Kingston upon Thames, just outside London; it was designed in a version of Wren’s Hampton Court style, something of an optimistic gesture given that the proximity of Webb’s store to the real thing makes an unflattering comparison easily achievable. Bentalls was gutted in stages between 1987 and 1992 for a new shopping center; a publication called The Bentall Centre Fact File, put out by the developers, credits the old building not to Maurice Webb but to his more famous father, just as plenty of dull buildings by Peter Paul Pugin are still often credited by their residents to his father Augustus.18 Furthermore, anyone visiting Kingston today will soon have their attention drawn by the much-admired branch of the John Lewis department store chain, designed in 1979 by Ahrends, Burton and Koralek, which, unfortunately for Webb’s reputation, is located opposite the remaining skin of his “Hampton Court” elevation: what critic will turn the other way with anything but contempt for poor Webb, even in the unlikely event that they have ever heard of him? The London: North West “Pevsner” condemns Webb’s other major structure, the 1929 Beit Building, in South Kensington for Imperial College, also inaccurately attributed online (by the college itself) to his father, as being in “the terrible style of the reactionaries of the 1920s”; and in London South the same authors say of Webb’s Kingston Guildhall that its peculiar curved entrance façade is “not a balanced or well composed front.”19 Thus little of Maurice Webb’s reputation will survive unless some brave soul from the Twentieth Century Society decides to rehabilitate him for the pleasure of the tiny number of enthusiasts who follow the careers of the cursed and the hopeless. Perhaps only his Quality Street-style north elevation to Robert Adam’s Royal Society of Arts, toward the Strand in London, will save him from oblivion.

Figure 4.4

The surviving façade of Maurice Webb’s Bentalls department store, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey: unfortunately it can easily be compared with the real baroque of Christopher Wren’s Hampton Court Palace nearby. Courtesy of Keith Diplock.

Fighting the walls

Much of interior design is inherently hopeless too, in this case in the sense that the results are unresolved or unresolvable, in the way that an architect generally tries to resolve the overall design of a building. One can see this as a battle between a designer brought in later, or without having been consulted on the structure and layout, and the hard concrete facts of the walls that have been put there by someone else, someone whose access to high-art criticism is always going to be easier than theirs. In any case, interior design is temporary, and meant to be temporary, whereas until recently architects believed—as Ruskin told them to—that they, by contrast, were building forever. And yet here I can see how much architectural criticism can learn from studying it. The sadnesses of it are more immediate than those of architecture, and anyone can spot them right away. I am looking at the moment at a recent book of photographs of British domestic interiors and I am struck—in spite of their attractiveness, which is real—by how sad they are. Houses that are too tidy for real life, too mannered; rooms inhabited, if that is the right word, by childless male couples and by assertive businesswomen, or so it appears from the small amount of explanatory text provided; here are rare and beautiful musical instruments that are, one supposes, little played; here are piles of magazines that are moved for different shots, for the sake of the camera; here are vases of flowers—the latter reminding me, unfairly, of the comment anecdotally attributed to the French interior designer Madeleine Castaing that wilting cut flowers are like dead bodies. There is much evidence here of the calculated self-image, much easier and cheaper to achieve through interior design than through a real building, many people still trusting the comment by P. A. Barron, writing between the two world wars, that “owners of charming houses are always charming people,” a declaration that is somehow unlikely to be true.20 If you live on your own, or if you do not have a family, you might well invest all your efforts in this paper-thin, transient thing that will die when you die, or beforehand: you will bequeath it to your favorite nephew, who will most likely put nearly all of it out in the skip.

The fakeness, the unreality, the slightly mystic quality attributed to inanimate things, the setting up of a façade against a largely artless and ugly world like putting on bold, inappropriate makeup—the whole enterprise has an antiestablishment feel to it, as had the oceans of pious gaudy junk that used to occupy Catholic churches in Protestant England. It is again the architecture of defiance. None of these things is “real” in the way architects defined the word: they are expressions of protest founded on a whole armory of wishful thinking. For surely these “charming” people are trying to put right, through the design of their houses, the one thing in their life that they can control, something that was not right for them in the past; just as there are people who spend time imagining a reconciliation to put right any kind of personal relationship that ended badly, trying to make the nasty person nice in their own minds, single-handedly, unable of course to do any such thing in reality.

The result can be a series of interiors within a single house that do not lie neatly with one another, or speak the same language as one another, in the way that the architecture of rooms within a building nearly always does. None of this is meant to suggest that the designers of domestic interiors are charlatans; far from it. There is no doubting the power of what an interior is like; I remember going back to the house I grew up in and seeing how my mother’s pretty decoration scheme had been replaced by horrible, artless colors: it caused me something of a real and lasting trauma. What I am saying is that interior design can shed a light on the hopeless aspect of architecture, the wanting something to be what it is not, with a limited budget, a narrow and fussy vision of completeness, and an avoidance of dealing with the big, expensive things. My picture book of romantic interiors projects a comprehensive image of the tremendous futility of what is, in purely architectural terms, a wasted effort, an attempt to create or re-create a beautiful life through the thin dimension only of walls and cushions. Maybe that is why I like it, for I also like the washed-out views of Edwardian and interwar interiors in the many books I collect on the subject: they are a further expression of my own hopelessness. I don’t need to read the accompanying text, which is anyway only rarely illuminating; just glimpsing the old photographs is enough to do the job.

I mentioned just now that there can be a battle between interior designers and architects, and twenty-five years ago I experienced this at first hand. A professional interior designer stripped out the interior (without permission) of an apartment in a smart part of London, revealed the underside of a sunken bath projecting from the floor above, panicked, and finally called in some architects—us—to sort it out. When pictures of the flat were subsequently published in a well-known interiors magazine, the involvement of architects in the project was completely ignored: she told the world that she had done it on her own. This episode illustrates to me something of the gulf between two professions that have less in common with one another than is generally thought by laymen. One of the things I was struck by when working myself in an architectural practice that specialized in remodeling the interiors of Victorian houses in London was that non-architects are so scared of moving staircases and doors—in reality no great problem or expense—that they will move everything else about in their idea of a plan in order to leave them where they are. This in itself expresses something further about the detached nature of interior design compared to architecture.

Here I am becoming a bully myself, of course, because of the suggestion, as an architect or architecture critic, that the only thing that matters is the fabric of the building itself and the things that the original architect thought should be affixed to it. We know that eighteenth-century architects working on high-prestige projects saw the design of the interior as being part of the house; in the past when I have claimed that Pugin was the first to design a coherent set of architectural details for both inside and out, I have been reminded by those with a more balanced view of history that Robert Adam, and top-end Georgian architects working on prestige projects, also did this. But it was Pugin who made it important to architects to maintain this coherence. He had achieved it in his domestic architecture by the time he finished his own house in Ramsgate in 1844, and from exactly then onward he went on to realize it on a spectacular scale at the Palace of Westminster: “You may search the Houses of Parliament from top to bottom,” wrote Voysey ecstatically in 1915, “and you will not find one superficial yard that is copied from any pre-existing building”—and there are, of course, many thousands of details there.21 The same complete control of the interior, exactly corresponding to and relating to the details of the exterior, is characteristic of the work of Pugin’s admirers fifty years later—Voysey and others—to the extent that by the turn of the twentieth century, so perfect is the fit between the details and the exact use and character of a room that each place in a house can be used by the resident only in precisely the way that the architect originally intended. The international influence of the British arts and crafts movement brought with it the common acceptance among designers that this should be the case, eventually creating what Hermann Muthesius went on to call “the emotion-laden furniture” that made these buildings impossibly stifling.22 At much the same time Adolf Loos coined the expression “Poor Little Rich Man” to satirize the way in which rich clients found themselves at the mercy of their architect’s Gesamtkunstwerk interior, to the extent that they had no freedom any more in what they could do, or even think, within their own houses.23

The high-art international modern movement was the third attempt at forcing on the general public the notion that architecture and interior design are indivisible. And yet they are not, which is why they keep coming apart in the great majority of buildings that are completed beneath the critical radar. As David Watkin wrote in his Radical Classicism: The Architecture of Quinlan Terry, responding to criticism, mainly in the Architectural Review, of the apparent conflict between the crafted neo-Georgian exteriors and the unremarkable modern office interiors of Terry’s Richmond Riverside scheme:

in the needless pursuit of the doctrine of “truth” in the religion of Modernist architecture, it has been insisted that interior and exterior should always be one and the same thing. However the complex story of architecture teaches us a very different lesson.24

It was in reaction to the stifling nature of arts and crafts design that architects turned back to the simplicity and versatility of Georgian-type rooms, where you could put your furniture and yourself where you pleased and when you felt like it. The interior designers of this period were doing exactly what the unremembered Edwardian architects in chapter 2 were doing: they were creating, with the help of furniture shop decorators, a variety of styles and atmospheres under the same roof. This was also the period when there was a flowering of fine illustrated children’s books. I wonder whether some of those images might themselves be a reflection of the hopelessness of the interior designer, a retreat into infantilization when faced with the reality of adulthood. The whole enterprise of interior design has about it all the hallmarks of an inherently tragic endeavor.

Setting the rules

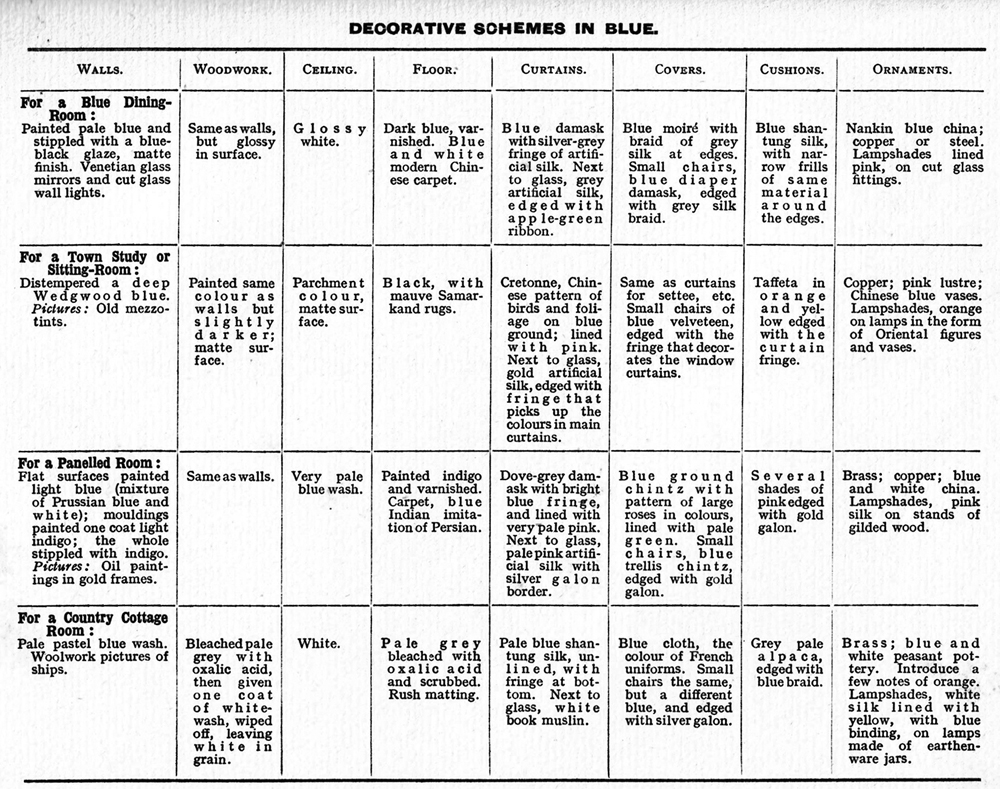

Although coherence between rooms is less important for interior designers and their clients, the creation of a total environment, preferably a fantastic one of some sort, is much valued. The great achievement of Castaing is derived from the fact that her rooms were made up from a dense and eclectic mixture of pieces—including, after the Second World War, the English Regency—so their power lay in her layering of historical associations; the confused sense of completeness that they evidently projected elicited associations and references from several conflicting sources at once. Basil Ionides, a quite different designer from the interwar period, also aimed to create complete environments, but using other means. His 1926 book Colour and Interior Decoration provides charts that tell the amateur decorator what colors and materials should be used in details as small as the fringes of curtains or lampshades, and the mounts of pictures, giving the lie, to anyone who thought otherwise, to the idea that only architects and perhaps set or theater designers are interested in total control. The book has the commanding nature that one would expect from a designer who grew up in Kensington in a family circle rooted in collecting and in the aesthetic movement—his father Luke was a friend of J. M. Whistler, and his uncle and aunt were both patrons and friends of William Morris and the pre-Raphaelite artists. Basil Ionides worked in upper-class circles, was friendly with the aristocratic designers Syrie Maugham and Mrs. Guy Bethell (he illustrated her work in Colour and Interior Decoration), and designed short-lived interiors for Claridges and the Savoy, the smart London hotels.

Figure 4.5

A table from Basil Ionides’ Colour and Interior Decoration (1926) which describes how precisely to achieve a desired effect.

No doubt a powerful attraction in the work of both Castaing (mess, eclecticism) and Ionides (order, coherence), which on the face of it seem quite distinct, is the fact that the clients of interior designers seem to have a particular fear of one small element being out of place, one feature which will in some way betray their anxieties about their social status or personal taste. Ionides’ two books certainly project a minefield for the insecure, because in his opinion making a mistake in the precise hue of a color can put the decorator in danger of committing the most terrible social faux pas: “A bright pink carpet is an abomination, but a crushed strawberry or old rose one may be effective. . . . Pink and gold are apt to cloy, but a little gold with pink is effective. . . . Pink and blue is flowery in its effect, but the blue must be light in tone and should be on the warm purple side . . .” are typical examples from a single page of Colour and Interior Decoration.25 This seems to go some way beyond an architect’s fear that a detail has not been resolved satisfactorily, which is a matter not of class or taste but simply of coherence and logic. I remember one client of ours, remodeling a large house in South Kensington, who was worried about the height of light switches. He had them moved up the wall and then, after thinking and worrying, back down again—his fear was that they would shame him, either from being too high, and thus low-class, or, worse, from being too low to avoid being too high, forcing him to commit a lower-middle-class genteelism as bad as saying “toilet” for lavatory. The design of non-Victorian items such as shower cubicles also distressed him, because there was no established high-class precedent. The nitpicking by upper-middle-class viewers of supposedly solecistic details spotted in the internationally successful TV drama Downton Abbey shows how perpetually fascinating these things are for the British.26 If you are an interior designer associated with the wrong class of person, then you are cast into outer darkness as far as the class which sees itself as superior is concerned. This is not generally true of architecture, which has written into its history and consciousness the importance of being able to deal with cheap and simple houses, and where the significance of social class lies only in budgets.

Looking at the practice of interior design thus not only illustrates the hopeless side of architecture, it also greatly increases the scope of that hopelessness, which in turn gives critics much more to think and write about. It more usually projects fantastic rooms, divorced from the reality of the space they occupy, reinforced by unimportant but strict rules, a device usually seen as the refuge of the administrator rather than of the creative artist; it is transient; it evades real problems; it cannot create space, merely divide it up with small pieces; its literature is narrow, and similarly divided into small areas. It tries to create a completeness that is distinct from the physical nature of building and is more closely linked with the ideal world of an individual—which in turn means that, unlike nearly all architecture, a single person can shape and control it. It is possible, of course, to tell the story of its development over time, but this does not evolve in the way that architectural history does; it therefore has no real narrative behind it beyond a reflection on a series of trends in consumerism and social aspiration. All of these things suggest approaches that ought to be useful to architecture critics. The fact that interior design is of so broad an interest to so many people, as witnessed by the array of magazines about it addressed to different audiences, suggests that an appreciation of it is much broader than appreciation of architecture. And therefore, in spite of its lack of substance, it seems to project something which most writing about architecture lacks. The difference between interior design and the design of whole towns, which I shall look at in conclusion, is not much more than a matter of degree; but once one deploys the apprehensions involved in the design of the spare bedroom, or the private sitting room, at the scale of the city, one starts to be confronted with an image of desperate inadequacy.

I will do such things,—

says the decorator with the roll of wallpaper upstairs,

What they are, yet I know not: but they shall be

The terrors of the earth.27

Historical hopelessness and what it is hiding

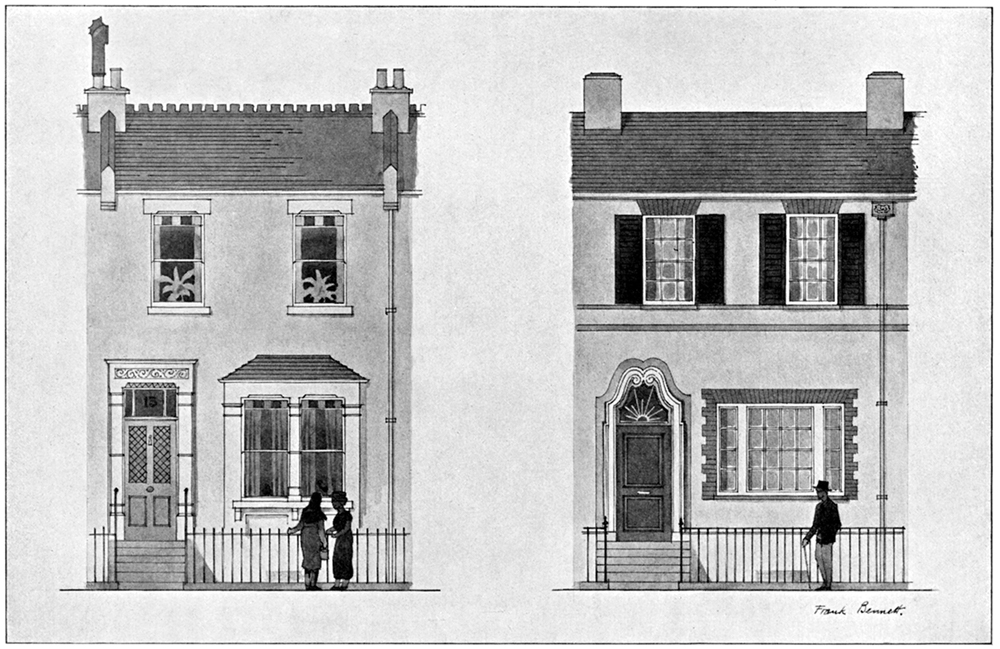

Just as some elements of the great works of John Vanbrugh end up on the front elevations of public housing, so aspects of the creations of the famous practitioners of interior design find themselves recommended for modest suburban dwellings. I have a copy of a book called The House Improved, written by Randal Phillips, a prolific author on the subject of modern homes and what to do with them, published by Country Life in 1931: it is a book that tells aspiring homemakers how, having given up any hope of commissioning a new house in the postwar economic climate, they can convert an existing one into a comfortable modern residence. The book shows its readers how to enter into a hopeless battle with Victorian architecture: how to demolish, or mutilate, or alter it out of existence so that it becomes streamlined, pastel-colored, modern. There were many books of this kind which emerged together with the development of the interior designer as a person distinct from a representative of a furniture shop, marking again the point at which interior design once more becomes divorced from architectural criticism, as it had been in the days when each room in a large Victorian house might have been designed in a different style. This is one which suggests a number of battle lines between the exterior and interiors of the buildings. But more interesting for me is the fact that once one looks into the projects carefully, and follows up their subsequent lives, one discovers that the book is full of architectural tragedies in different senses: some violent, some pathetic.

Phillips’s book opens with a view of a pair of houses in Palace Street, close to Buckingham Palace; the right-hand one is a Georgian terraced cottage, with ugly, narrow, two-paned sash windows and no ornament at all except for the fact that there is a semicircular brick fanlight; the house to the left has been turned into Quality Street by forcing onto its fabric genteel decoration and details: the windows have become “Queen Anne,” employing the type of timber window construction with prominent sash cord boxes that was outlawed in 1707 as a measure against fire spread; there is a Regency-era bow window; and there is a doorcase from anywhere in the eighteenth century, a perfect hybrid very soon imitated, as it happens, by all the other house-owners in the terrace.28

Converting a workers’ terrace close to Buckingham Palace into Quality Street was a perfectly reasonable endeavor, but few of Phillips’s readers would have been able to manage it; to them are dedicated the sections that follow, explaining how to camouflage an ornamental Victorian marble fireplace into a modern one with some boxing in; ornamental balusters, likewise, with more boxing in; the application of wallboard, a cheap and nasty material, in order to arrive at a streamlined contemporary interior; how to apply white stucco and French-looking shutters to an ugly house to make it look pretty.29 The strangest project of the book is the conversion—by Percy Morley Horder, later a successful commercial and institutional architect—of the St. John’s Wood house of Lawrence Weaver, Country Life’s most distinguished architectural writer of the period.30 Here Morley Horder removed the raised ground-floor entrance that is so characteristic of the large mid-Victorian detached townhouses of the period and brought visitors in through the basement, creating a peculiar unbalanced effect on the street façade as part of his assault on the traditional layout of the kitchen offices. It is hardly surprising that a subsequent remodeling has returned the front door to the upper ground floor, taking with it, as an interesting architectural relic, Weaver’s fanlight, now the only detail in the house that has survived from his period as well as being the only trace of the Horder project that recalls his short-lived and thus failed intervention.

Figure 4.6

Before and after: an attempt at converting the front of a plain Victorian terraced house into a stylish modern façade, from Randal Phillips’s The House Improved.

Other projects in the book have considerable charm, yet they too, as it turns out, may be concealing tragedies: there is a Mayfair stable behind Park Lane converted solecistically (twice over) into a rural cottage, now demolished; and a Kensington studio in Aubrey Walk made into a rustic retreat—with prominent ceiling joists—for the disappointed widow of the editor of Boys of the Empire, “A magazine for British Boys all over the world,” the aim of which was “To promote and strengthen a worthy imperial spirit in British-born boys.”31 Lady Handley Spicer, who commissioned the conversion, might have been in need of modest and small-scale accommodation because her husband, whom she had sued for restitution of conjugal rights, had recently committed suicide. Of course none of this desperately sad and personal information was mentioned by Phillips, but its discovery certainly shows how a little digging (even, I confess, in this case from Wikipedia) can start to tell the parts of the story that an architecture critic might miss or find irrelevant.32

Spicer’s tiny house was converted by Arthur T. Bolton, curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum at the time; like Bolton’s other buildings, it rewards some close attention.33 The house he designed for himself in Birchington on the north Kent coast—immortalized in his well-known Small Country Houses of Today by none other than Lawrence Weaver, whom we have just met—has been horribly enlarged and mutilated in modern times.34 The world of small house building in any country is not so large that it is impossible to map out the links between the various people and the sites, and from these we get a much broader picture of architectural history, one with links to the culture and society of a particular time. And in turn, an interesting story of some sort will inevitably emerge.

Striking contrasts, or architectural solecisms and anachronisms expressed in the interior and the exterior of buildings, are by no means a sign of tragedy. Although high-art architecture in all its forms generally retained the integration between the interior design and the exterior whatever the style, architects sometimes created an exaggerated contrast between a formal interior and an informal exterior: Edwin Lutyens himself did this in 1908–1909 at Whalton Manor in Northumberland, where he placed a grand staircase and set of rooms, including a circular drawing room, behind the little-altered façade of a row of old cottages. Field also did it, on a smaller scale—from my copy of W. Shaw Sparrow’s Flats, Urban Houses and Cottage Homes one can see that the plain rendered Edwardian-Tudor-vernacular of the exterior of a house called Hookerel, close to Field’s own home by Woking golf course in Surrey, nicely conceals a white-painted, formal classical staircase and interiors; and Field’s more successful contemporary E. Guy Dawber installed grand, overscaled but authentically Queen Anne-style ornamental plaster ceilings to low rooms in his redbrick, red-tiled vernacular-style cottage in Berkshire.35 In all these cases, the contrast was intentional, designed to create an artful paradox: the coherence of the overall design lay in precisely that contrast. It is a shame that architects do not seem able to attempt this nowadays, and when circumstances demand it—as in the case of Terry’s Richmond scheme or his (in this respect) comparable Margaret Thatcher Infirmary of 2005–2008 at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea—the result seems to be apology or embarrassment rather than proud resolution.36

In any case, most people did not see the architect’s prized qualities of coherence and integration as important, and still do not. As architectural magazines turned modernist in the mid-1930s—as we saw happen to the Architects’ Journal—the advertisements in those same magazines, and the interior design press, remained resolutely eclectic. It is hardly surprising that the modern profession of interior designer emerges as the idea wanes, among those who could afford it, that the person who does the inside of a house must necessarily be the person who does the outside. Maybe the reason for this is the one that Phillips identified—that the building of a new house may be impossible, so one has to make the best of an unsatisfactory or indeed hopeless or almost hopeless situation; maybe another reason was the terrific range of potential interiors that designers across the whole range of the market were then offering: Regency; Tudor; “Queen Anne,” generally available through the furnishing departments of the large stores. We saw that Eltham Palace, like many other top-end rich people’s houses of the period, had interiors in different styles; only the minor ones were devised by Seely and Paget themselves, and even then not very remarkably. This seems to be what people want, if they can afford it, and to my mind there is nothing wrong with it.

There is no suggestion either that all interior design is attempting to realize the same thing, any more than all architecture is attempting the same thing; in fact the vast number of interior design magazines currently available in the United States and Britain, not to mention elsewhere, gives a good impression of the range available. A fact that is possibly not appreciated consciously by the readers of these magazines is that each one aims at a readership with a different but identifiable set of priorities; the range from Condé Nast, for example, is easily definable. House & Garden illustrates the kind of interiors that anyone can achieve with almost any building providing they have the money; by contrast, The World of Interiors, to which I have contributed for nearly twenty-five years, presents interiors that are not achievable by the average reader because they rely, for their impact, on historical situations, or very unusual architectural circumstances, or a degree of idiosyncratic creativity. In each case this is precisely what attracts readers to buy a copy. If you look through what is on offer at even only a medium-sized newsagent’s, you can identify the different parts of the market: there are, for example, magazines aimed at those who want to achieve a “green” interior, or a historical one, or a historical one on a low budget, or something they can make themselves. In each case there is usually also an impressive degree of editorial consistency. I recommend to aspiring writers hoping to freelance in this market that they buy the whole lot, and decide which one speaks to them directly: there are so many available that they are bound to find something. Then all they have to do is to imitate the style of writing of that publication, and they may well quickly be adopted as a contributor.

This variety of writing, some of it based on only very little actual information, all contributes to a wider understanding of what interior design is about; architectural writing does not have anything like this range. The only type of writing on interior design that I find incomprehensible is that found in the interiors supplements of the regular daily broadsheet newspapers: these generally praise places the attraction of which is to me entirely hidden. Sometimes they are written by the real-estate correspondents who pride themselves, I suspect, on total detachment from the whims of architects, whose names they sometimes even omit from the article. The newspapers’ editors seem to believe (and they are surely right) that the real-estate approach to interior design has a readership much larger than that of architectural criticism. In this respect there is a certain parallel between this and popular archaeology, which—inexplicably to me and to greater people than me, such as David Watkin—is enormously popular and politically strong: perhaps it is because most people see things in simple concrete terms, and cannot cope with bigger and more conceptual ideas.37 Perhaps also some people like to see their world defined in small, quantifiable items that they can control. The battle lines between the different types of writing on interior design can be as fascinating as those between the different types of architecture, and they can draw more people into a circle of debate. But a battle it is, which means that, like every other branch of architecture, it has not only winners and losers, but also stages of retrenchment and, finally, of loss.