“Are you quite sure?” Aunt Isa asked. “It goes without saying that we’ll help you if you’re wrong, and they attack you. But it could be dangerous.”

“We’re already in danger,” I said. “Waiting here in the drawing room might feel less dangerous, but it really isn’t.” How I wished that Cat were here, then I would feel a lot less scared. Cat was always so good at making me feel brave.

Aunt Isa smiled to me in a very Aunt Isa way. She cupped my face in her hands and gave me a quick peck on my forehead.

“You’re growing, Clara,” she said. “It’s good to see.”

Oscar, too, looked a little surprised at my volunteering, but for once he kept his mouth shut.

I took a deep breath. I felt as if I should be running on the spot or doing some push-ups. I mean, that’s what you do before a major sports challenge isn’t it, warm up? And this was much more difficult.

I opened the door to the landing. It was quiet outside, just as before, but possibly a little darker. Perhaps it had clouded over outside. Or maybe it was all in my mind. I could sense the sisters more than I could see them. This still, motionless waiting that wasn’t sleep.

You walked past them less than an hour ago, I reminded myself. They didn’t even twitch. You can walk past them now. Remember the seagulls. Remember the wild dogs – especially Lop-Ear. For whatever reason they will leave you alone, or… at least they won’t bite you.

I started walking. I could have run, but I decided against it – if you’re tiptoeing past a guard dog, it’s a really bad idea to start running because it’ll chase you just by instinct. So I walked, one step, two steps towards the stairs.

I thought I heard a flutter. I looked up. A few of the nearest sisters stretched their wings and, for the first time, I could see their heads.

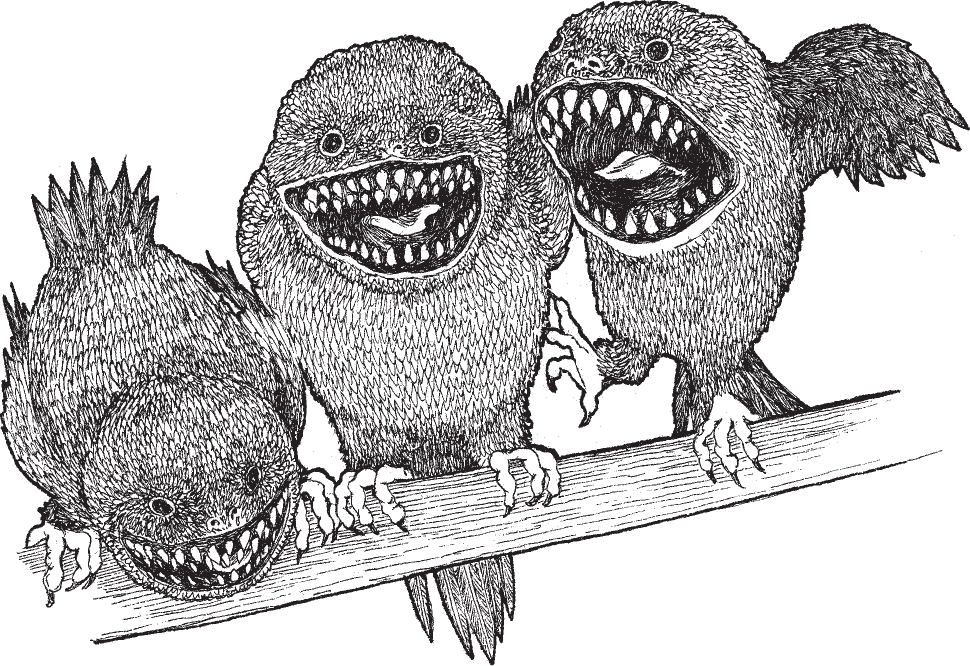

Perhaps it was just as well that I hadn’t seen them earlier because I’m not sure I would have dared venture outside. They had no beaks – to that extent they bore a slight resemblance to The Nothing. But instead of a lost little girl’s face, there was… practically nothing but a huge mouth. The eyes were reduced to shiny pinheads in the feathers, and just like Oscar had said, they had shark jaws bursting with sharp, triangular teeth, not just one row, but two or three.

I stopped in my tracks. I didn’t mean to. I really didn’t mean to.

Come on, I told myself. Onwards. OK, so they’re looking at you. That won’t kill you. Keep moving…

I took a few more steps, but I couldn’t help make them a little faster. I’d almost reached the stairs now. I wouldn’t say I was running, but neither was I out for a leisurely stroll.

The minute I put my foot on the first step, I heard a huge whoosh. I looked up. The whole stairwell had come alive. A swarm of sisters had taken to their wings as if controlled by a single will.

Now I ran. I made a dash for the bottom, but I still only managed a few steps before they were on me.

“Go away!” I screamed at the top of my wildwitch voice. “GO AWAY!”

I flailed my arms about as I ran, and I did hit some of them, but there were just so many of them. Thud. Thud. Thud. They hit my back and my head, my shoulders and my chest, my arms and my legs like feathery rubber bullets.

It was horrible, but I quickly realized that they weren’t actually sinking their teeth into me. In that way they did act just like the wild dogs and the seagulls. As long as I could keep going long enough to reach the front door, as long as I could make it outside…

I forced myself to carry on. I stopped lashing out at them, except when they aimed themselves directly at my face. But the strikes continued and they began attaching themselves to me with their claws. My body grew heavier and heavier, and my foot caught on the edge of a step because I failed to raise it high enough. Losing my balance, I made a desperate grab for the banister, but my arms weighed much more than they usually did. I was half turned around by the weight on my back and I fell, tumbling and landing not on the hard stairs, but on top of hundreds of soft bodies. Some of them were squashed; I heard the sound of delicate, light bones snapping like twigs and felt a wet warmth against my hip. It didn’t hurt. It wasn’t my blood. But the weight on top of me doubled abruptly.

I’m going to suffocate, I thought, and started bashing them again with my heavy arms, kicking them with my heavy legs, twisting my heavy body. I made it halfway to my feet, but fell back again, fighting to keep from being submerged in a flood of feathered bodies…

“Clara!” It was Oscar calling out to me, I thought, but he sounded much further away than he really was.

“Turn back!” Aunt Isa’s voice cut through the whirr of wings. “Clara, you can’t do it. Come back here!” Then a shrill, ear-piercing note rang out, a wildsong, but a form of wildsong I’d never heard before – a war cry that was an attack in itself. It seemed to pierce the mass of feathered bodies, and the weight on me eased a little. I managed to scramble to my feet and reach the banister. Clinging to it for dear life, I hauled myself up a step or two, when suddenly a hand grabbed mine. I batted a sister wing away from my face and could see that the hand belonged to Shanaia. She was dragging me back up the stairs while her wildsong keening grew louder and louder, and I couldn’t believe how all that sound could come out of just one girl. Aunt Isa had started singing too, and I could see both her and Oscar beating off the sisters, not with their bare hands, but with heavy books they used almost as if they were baseball bats and the sister birds were balls. With Shanaia’s help I made it back onto the landing, and when Aunt Isa got hold of my other arm, I was able to stagger the last few paces back into the drawing room.

Hoot-Hoot only just made it inside before Oscar slammed the door shut. Hoot-Hoot had fought too, I could see. He had blood on his beak and on one wing. Shanaia grabbed a book and slammed it down on the head of one of the sister birds that had chased after us; Aunt Isa brutally tore a couple more out of my hair and off my back, and wrung their necks as if they were chickens for the dinner plate.

Aunt Isa, Oscar and Shanaia were all bleeding from fresh injuries. Shanaia’s were the worst, one shoulder looked like someone had tried to push it through a shredder. Her leather jacket was in tatters, and her naked, bloody shoulder stuck out through the lining. There was hardly any skin left. In one place, something blue and sinewy could be glimpsed in the depths of the raw redness of the gash. Shanaia hadn’t guarded herself at all, she had fought simply to save me.

I was the only person without a scratch and I felt weirdly guilty about it. I had been congratulating myself for trying to save them, but instead they’d ended up coming to my rescue and paid for it with cuts and blood and pain.

“I’m sorry,” I said, although strictly speaking I hadn’t done anything wrong.

“It was worth a try,” was all Aunt Isa said, and placed her hands on Shanaia’s shoulders. The wildsong returned, this time the calm, humming singsong so much more familiar to me than Shanaia’s wild battle cry, and it looked as if it was stemming the bleeding a little. Shanaia was deathly pale, and her black-rimmed eyes looked like cinders in her white face.

“It’s no good,” Oscar panted, sucking his wrist, which had acquired yet another shark bird bite. “We can’t get out that way.”

“Can’t we use the wildways?” I asked.

Aunt Isa shook her head. “Few wildwitches can find the wildways indoors,” she said. “Most of us need the sky above our heads and grass, soil or rock under our feet.”

Cat could do it, I thought. But then again, he needed only a hole in the fog big enough for him to slip through – a kind of sophisticated cat flap. Besides, I was starting to realize that Cat didn’t really think most of the laws of the universe applied to him.

Aunt Isa sang another wildsong for Shanaia’s shoulder. And another one.

“We haven’t even got water,” she said. “Oscar, check the drinks cabinet to see if there’s anything other than mediocre sherry. Vodka or schnapps would be the best.”

“Aunt Abbie preferred brandy,” Shanaia said in a croaky voice. “I don’t think she was much of a vodka drinker.”

“Why is that so important?” I asked.

“The wound is quite deep,” Aunt Isa explained. “Even with wildsong… it would be good to get it cleaned up. And vodka is almost pure alcohol.”

“There’s nothing like that,” said Oscar, who had opened a rather large mahogany cabinet that was clearly not, after all, the innocent bookshelf it had first appeared to be. “But there is some whisky. Will that do?”

“I guess it’s better than nothing,” Aunt Isa said.

Oscar brought the bottle, and Aunt Isa carefully tipped a little of the whisky into Shanaia’s cut.

Shanaia inhaled sharply. It clearly stung.

“I’m sorry, sweetheart,” Aunt Isa said quietly. “But…”

“I know,” Shanaia said through clenched teeth. “I know.”

However, the strange thing was that despite her injuries and the pain, she looked better than she had when I first entered the drawing room. The lost and resigned expression had gone. Her eyes had come alive once more.

“Thank you for saving me,” I said. “I wouldn’t have made it up the stairs without you.”

She didn’t exactly smile, but she did nod.

“Hey, what about us?” Oscar said. “We saved you too.”

“Yes, of course you did. Thank you so much.”

“How very charming,” The Nothing suddenly jeered in Chimera’s voice. “But I see that you still haven’t got the message.”

We turned as one to The Nothing, still lying on the floor with her legs in the air, but obviously useable as Chimera’s mouthpiece all the same. At that moment there was a loud crash from one of the three tall windows in the drawing room. I only caught a brief glimpse of a large, white body, then it was gone and only a bloody imprint remained on the window pane. Then the next seagull attacked. Another crash. And the next. It wasn’t until the sixth seagull’s attempt that the window shattered and a shower of large and small shards of glass rained down on the rug.

The seagulls made no attempt to get inside. Their mission seemed purely to break the glass. And they didn’t stop until all three windows lay shattered on the floor and the winter wind howled through the bloodstained, jagged holes.

“You have one hour to find my book,” Chimera’s voice said. “Then the sisters will come for you.”