ONE OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL HORROR MOVIES EVER MADE—AND ALMOST LOST FOREVER.

The story behind Nosferatu is almost as frightening as the film itself, at least from the perspective of historic film preservation. Today an undisputed masterpiece of world cinema, F. W. Murnau’s most celebrated achievement was the first, though completely unauthorized, film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and the specter of copyright infringement haunted it from the beginning, endangering its very survival. Most silent films have been lost through neglect (75 percent, according to the Library of Congress). In the case of Nosferatu, the film was the target of a campaign aimed at its deliberate destruction. Had Nosferatu not survived, the entire trajectory of fantastic filmmaking could well have been materially altered—and greatly impoverished.

Nosferatu is a prime example of German expressionism, a broad category covering a range of artistic experimentation arising from the cataclysm of World War I, and often employing grotesquely distorted characters and situations, allegory, and social criticism. In cinema, expressionism employed stylized theatrical settings and a dramatic use of light and shadow. The most influential expressionist film was another horror story: Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), which featured skewed sets and sharp shadows reflecting a preoccupation with nightmares and insanity. The story of a mesmeric carnival charlatan (Werner Krauss) who controls a murderous somnambulist (Conrad Veidt) has been interpreted as a parable of the Great War itself, in which untold numbers of soldiers were sent forth by madmen in positions of power to kill and be killed.

Blood vessel: the vampire commandeers a ship, killing its crew.

The guiding force behind Nosferatu was the artist and occultist Albin Grau, who in 1921 founded an independent production company, Prana Film, dedicated to supernatural themes. In the end, Nosferatu would be its only realized project. Grau hired Henrik Galeen, a screenwriter and actor known for his work on The Golem (1915), and the rising German director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Grau took a hands-on approach to his vision, acting not only as producer but also as art director and costume designer; he additionally created all the publicity materials and posters.

Grau attributed the film’s genesis to vampire legends he heard recounted in Serbia during his service in World War I. Like Caligari, Nosferatu told a story by way of allegory; Grau regarded the war itself as a “cosmic vampire” that had drained the lifeblood of Europe. He also interpreted Dracula (whom he renamed Count Orlok) as a rat-like vector of plague—a highly effective and grimly appropriate choice. Overcrowded hospitals attending maimed soldiers had proved a major breeding ground for the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1920. Like the fantasy world of Nosferatu, Europe itself was gripped by a plague, which by some accounts took more lives than the war.

No one knows exactly where the word “Nosferatu” originated. Bram Stoker assumed it was the Romanian/Transylvanian word for “vampire” (based on a claim made by a Scottish folklorist), but it cannot in fact be definitively traced to any language. Nonetheless, it sounds authentically ancient and convincingly creepy, and it is now generally accepted as a synonym for “undead.”

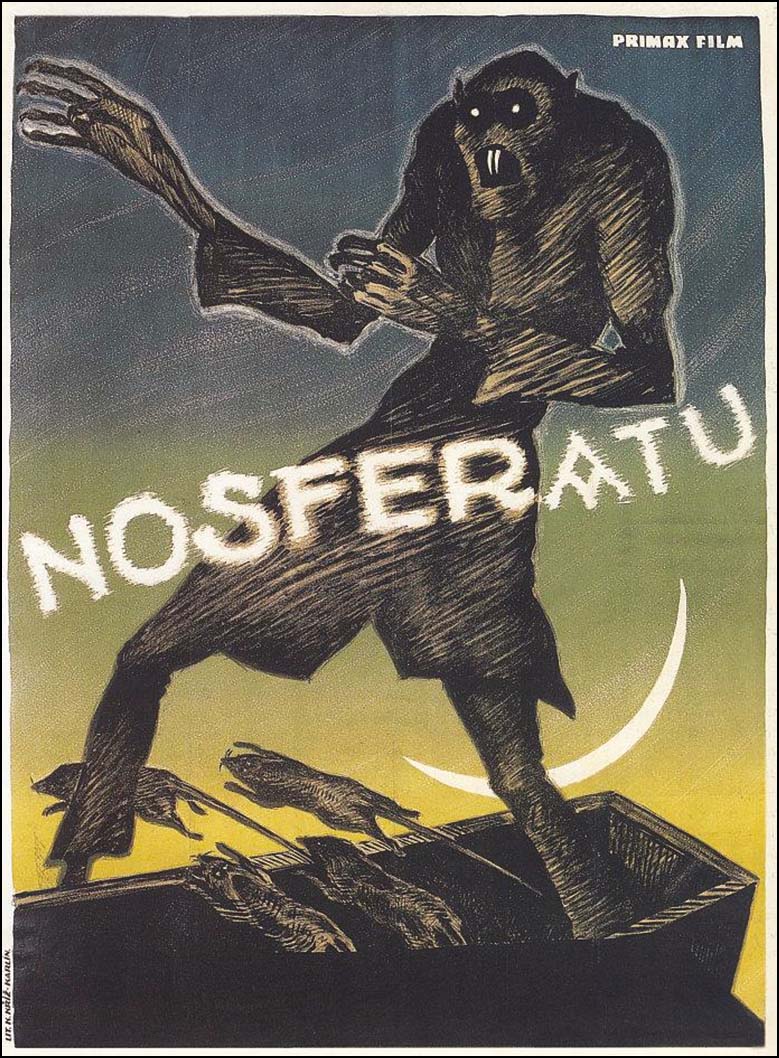

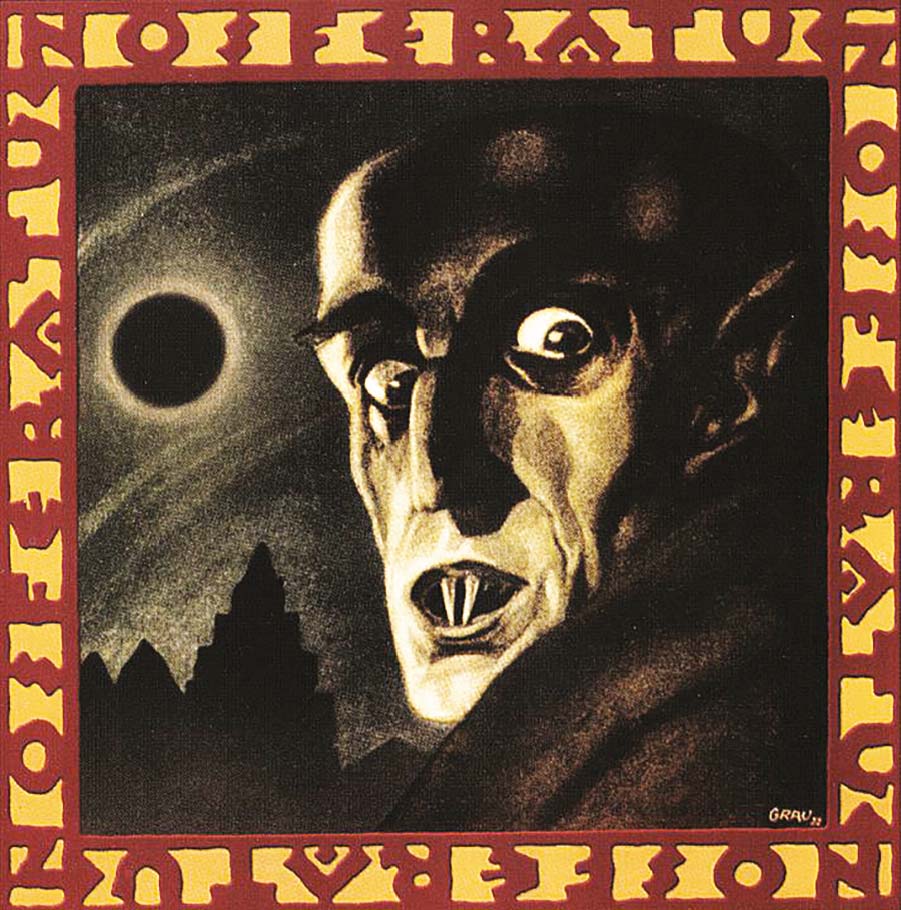

Original promotional art by Albin Grau ABOVE Czech poster BELOW Russian herald

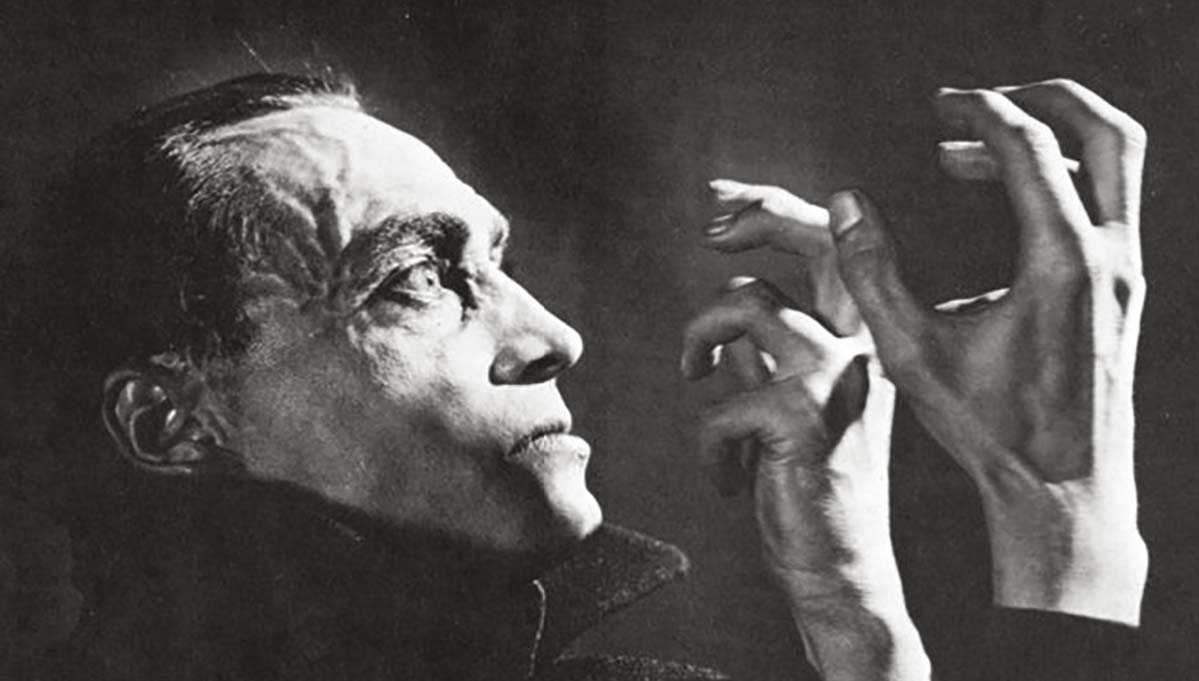

Whereas Dracula is set contemporaneously in Stoker’s Victorian age, Nosferatu takes place much earlier in the nineteenth century, during the age of the Brothers Grimm, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and the full flowering of literary Romanticism. The characters are archetypal and simply delineated, like figures in a fairy tale. The actors all came from the German stage, which had already been advancing the acting and design conventions that greatly influenced expressionist film. The most memorable performance is that of Max Schreck as Orlok/Dracula, an indelibly disturbing amalgam of human and rat. Stoker’s Dracula was also repulsive—a fact usually overlooked by filmmakers—but Grau’s conception exceeded even Stoker’s vision.

While Nosferatu changed many aspects of Stoker’s book, it retained others. Dracula is an epistolary novel—an assemblage of letters, diaries, newspaper clippings, and other documents—and Nosferatu parallels the technique through an extensive use of calligraphic title cards that provide an omniscient narrative framework. A direct borrowing from Dracula is the use of a ship captain’s harrowing log, recounting the stowaway vampire’s commandeering of the doomed vessel.

One of the most famous and chilling images in film history occurs after the heroine Ellen (Greta Schroeder) learns that the vampire can be destroyed by a virtuous woman willingly inviting the monster to her bed and keeping him there until sunrise. Ellen makes the invitation by flinging open her window, and then, in what amounts to the most iconic pair of shots in German expressionist film, Count Orlok’s shadow is seen stealing up the stairs to her bedroom, followed by the dark shape of his claw-like hand stretching out to her door.

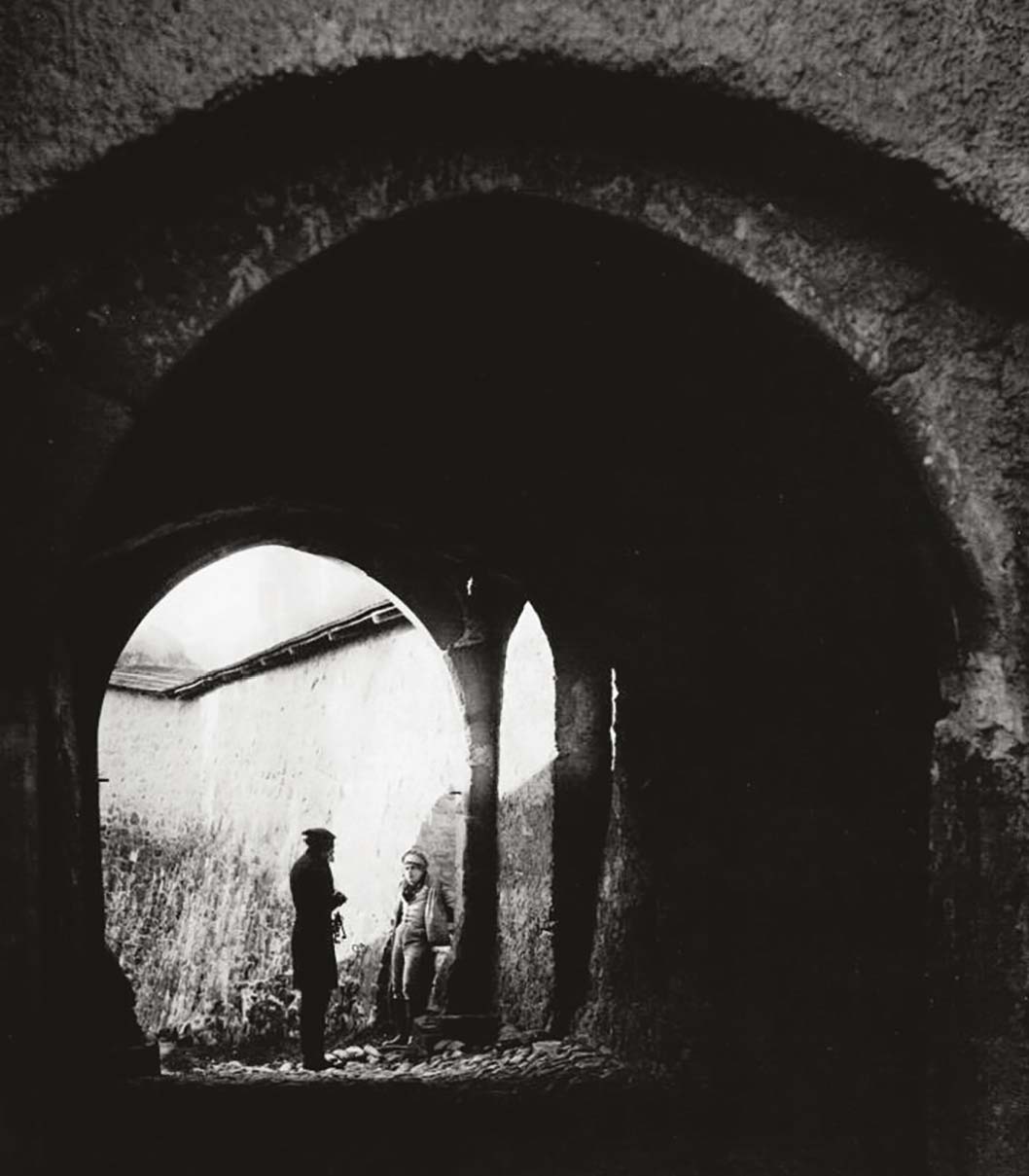

Hutter discovers his host’s resting place and understands his true nature.

A gala Berlin premiere, including a costume ball, was held in early 1922. Grau’s publicity efforts were ambitious and extensive, reportedly costing more than the film’s entire production budget, and word of the film’s existence soon reached the widow of Bram Stoker, who had died ten years earlier. Florence Stoker struggled to maintain a stable income from Dracula’s royalties and was eager to exploit potential stage and film adaptations. Universal Pictures had considered a film version as early as 1915, but passed because of irregularities with the book’s American copyright registration. Nevertheless, in 1920 Universal made a press announcement that it was considering Dracula as the next vehicle for its up-and-coming “mystery man” director Tod Browning—who, of course, would ultimately helm the famous 1931 version.

When Nosferatu appeared, the filmmakers naively made no attempt to hide the fact that it was “freely adapted” from Dracula. Florence Stoker was outraged at the brazen infringement of her copyright and immediately enlisted the assistance of the British Society of Authors to help press a legal case. A three-year legal war ensued, which bankrupted Prana Film. The widow never collected money, but in 1925 she did win a ruling by the German courts, which officially declared Nosferatu an infringement of her copyright and ordered all prints of the film and its negative to be destroyed. But even without copyright protection, pirated copies of Nosferatu were soon surreptitiously escaping Germany, seeking refuge in foreign lands in much the same way that Dracula had fled his native Transylvania.

Count Orlok (Max Schreck) welcomes Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) to Transylvania.

Nosferatu, however, was not finished disturbing Florence Stoker’s dreams.

Because Nosferatu never had a proper American distribution, when Murnau, by then acclaimed for the Ufa production of Faust, relocated to Hollywood, interviewers and publicists didn’t know of the earlier film’s existence and never asked him about it. Murnau died tragically in a car crash in 1931, having never given an interview or other account of the film’s production. Nosferatu essentially vanished until the 1960s, when prints began to resurface and the full importance of its achievement was recognized. It has since been regularly revived, often accompanied by highly creative new orchestral scores performed live. A definitive restoration utilizing the best available elements was finally completed in 2013.

In 1979 Werner Herzog’s remake/homage, Nosferatu the Vampyre, starred Klaus Kinski closely resembling Schreck but playing Dracula as a tragic, lonely figure. In E. Elias Merhige’s Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a fictionalized account of the making of Murnau’s film, Willem Dafoe played Nosferatu/Schreck (the actor presented, cheekily enough, as an actual vampire), with John Malkovich as Murnau and Udo Kier as Albin Grau.

If you enjoyed Nosferatu (1922), you might also like:

THE HANDS OF ORLAC

PAN FILMS, 1924 (AUSTRIA/GERMANY)

Conrad Veidt recoils from the transplanted hands that have taken on a life of their own in The Hands of Orlac.