A CLASSIC TALE OF IMPOSSIBLE LOVE HAD ITS OWN STAR-CROSSED JOURNEY TO THE SCREEN.

Broken bodies and ruined faces were common sights on the streets of America in the 1920s, as untold numbers of maimed and disabled World War I veterans tried, often unsuccessfully, to merge back into society. Broken bodies and ruined faces were also a curiously persistent feature of Hollywood movies in the Jazz Age, particularly those starring the protean Lon Chaney—“The Man of a Thousand Faces”—and directed by Tod Browning. Chaney never actually played a wounded soldier, but the public’s need to confront the veterans’ plight, however indirectly, may go far to explain the popularity of Chaney’s trademark portrayals of disfigurement and disability.

In 1923, Universal Pictures released its sumptuous production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, featuring Chaney as the deformed Parisian bell ringer, Quasimodo. The actor’s established facility with greasepaint, putty, and prosthetics was given its biggest challenge to date, and he rose to the task by creating one of the most iconic characterizations of the silent era. During a trip to Paris, Universal’s president, Carl Laemmle, had made the acquaintance of the French mystery writer Gaston Leroux, who gave him a copy of his 1910 novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra. Immediately intrigued, Laemmle heeded his showman’s instincts and purchased the screen rights for Chaney.

Leroux’s story was, at its center, a modernized version of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s Beauty and the Beast. The title character is Erik, whose face is hideously deformed since birth. A musical genius in his own right, the “Opera Ghost” haunts the cellars and boxes of the Paris Opera and becomes romantically obsessed with a rising young singer, Christine Daaé (Mary Philbin in the film). When the opera management fails to promote Christine as he demands, Erik drops the opera house’s massive crystal chandelier on an unsuspecting audience. Amid the ensuing horror and confusion, Erik abducts Christine to his subterranean lair. Provoked by the face covering he wears, she rips away the mask, revealing the living death’s head he has kept hidden from the world. The rest of the story involves the efforts of Christine’s real-world lover, Raoul de Chagny (played by Norman Kerry), to rescue her, Christine’s pity for her kidnapper, his threat to dynamite the opera house, and the Phantom’s eventual death from the heartbreak of unrequited love.

The Phantom leads Christine (Mary Philbin), his “angel of music,” deep into the shadows of the opera house.

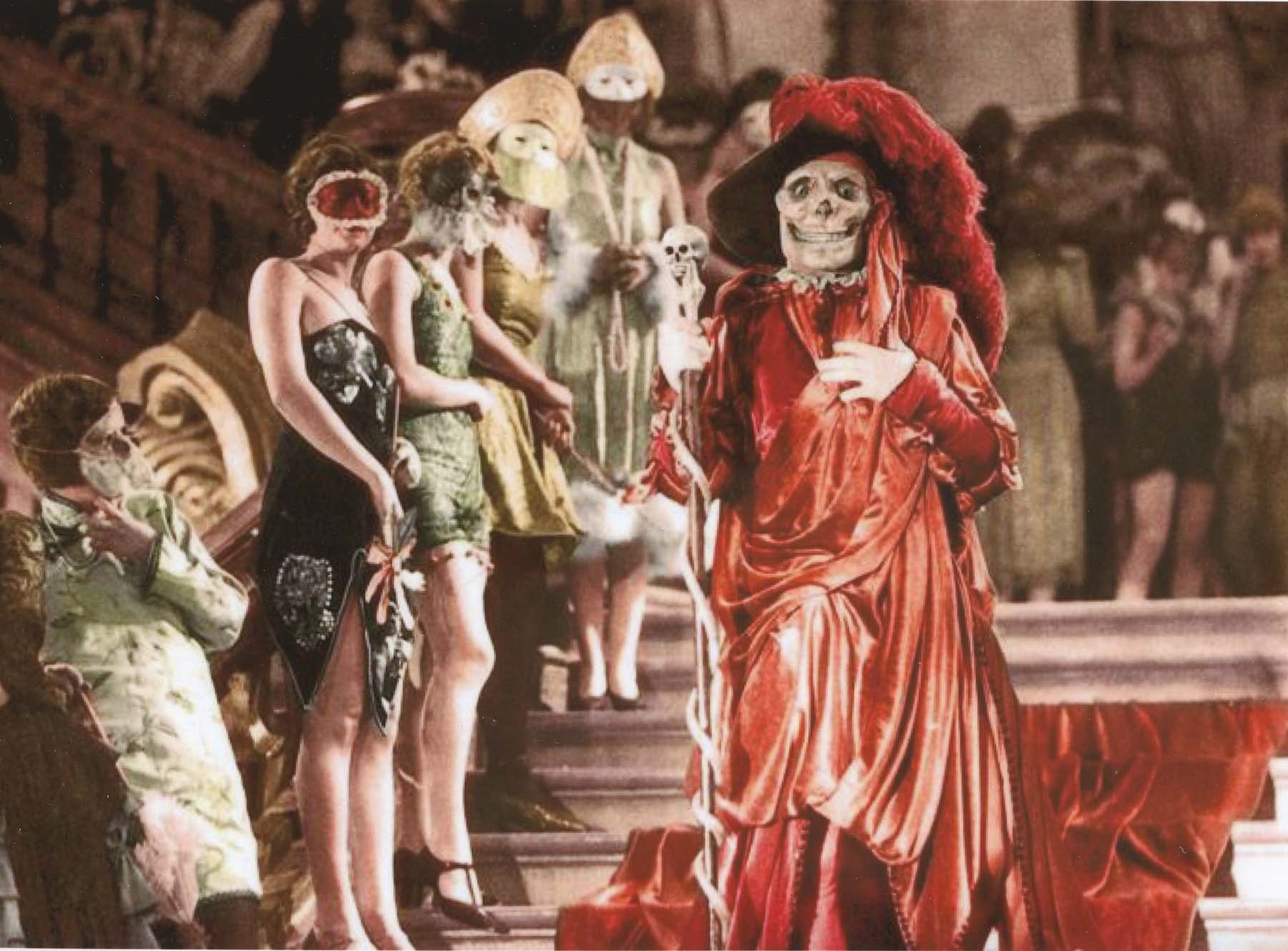

In the guise of the Red Death, the Phantom makes a daring public appearance at a masked ball.

Chaney’s makeup, withheld from the public in all advance publicity, re-created the look of a skull by enlarging the actor’s nostrils with dark paint and pulling up the tip of his nose with small hooks and fine wires hidden by makeup and putty. There are few cinema faces more indelible and iconic than Chaney’s Phantom, a single photo of which still has the power to immediately conjure the world of silent film.

Lon Chaney as Erik, the unforgettable Opera Ghost

To re-create the interior of the Paris Opera, Universal erected a new, steel-reinforced, state-of-the-art building—Stage 28—that could support the weight of massive sets and hundreds of extras. These extras played the audience members who witness the crashing of a full-scale crystal chandelier onto the stalls, and the revelers at a lavish masked ball that takes place on an exact replica of the Paris Opera’s grand staircase. Stage 28 achieved the distinction of being the world’s oldest working soundstage before its demolition in 2014, and the venerable opera boxes appeared in many other Universal films over the decades, the last being The Sting in 1973. The preserved sets were afterward occasionally undraped for photo shoots and documentaries.

The film had a Hollywood preview in January 1925 and was poorly received. The production had been compromised by director Rupert Julian, who clashed repeatedly with the cast, especially Chaney, who ultimately directed himself in most scenes. To protect its investment, the studio took the drastic step of reshooting the majority of the footage, adding subplots and comic relief that radically changed the film. In the process, Julian quit and was replaced by Edward Sedgwick. One of Sedgwick’s major contributions was replacing Erik’s mawkish, lovesick demise with an exciting chase as a mob storms the Phantom’s lair and then drowns him in the Seine. Nonetheless, an April preview in San Francisco proved a complete disaster; the audience actually jeered and booed. Film editor Maurice Pivar and Universal’s prolific (and at one point highest-paid) director Lois Weber were given the task of creating a third and final edit of the film. Weber had Carl Laemmle’s complete trust, and her extensive and trailblazing work as an actress, screenwriter, producer, and director made her unusually qualified to impose a workable dramatic shape on the troubled production.

In this original version of the film, the Phantom dies of a broken heart.

When the picture finally premiered in September 1925, with a general release in November, it clicked with audiences and reviewers alike. Its worldwide gross was $2 million, less than the $3.5 million earned by The Hunchback of Notre Dame but still enough to make it a major success. Chaney’s performance was widely praised, but Philbin’s doll-like demeanor failed to endear the actress to critics. Universal released a reworked, part-talking version in 1929, with music and new dialogue sequences featuring Philbin and Kerry.

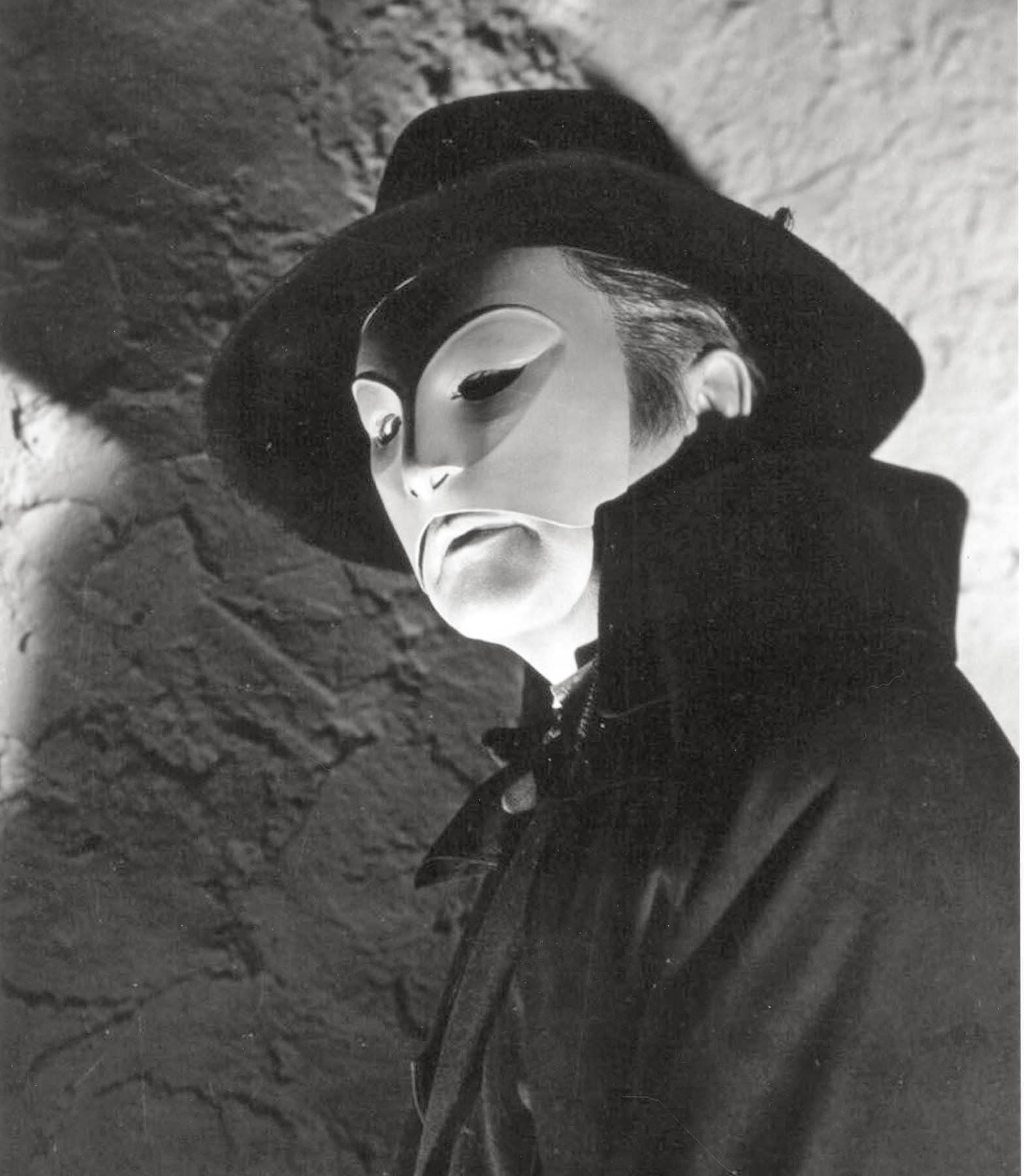

In the 1943 remake, Claude Rains wore a stylized mask patterned after his own face.

Notably, later screen versions of The Phantom of the Opera didn’t even try to replicate Chaney’s singular makeup achievement, although the 1957 Universal biopic Man of a Thousand Faces featured James Cagney in freely stylized interpretations of Chaney’s most famous portrayals. That film’s faces were created by Universal’s makeup chief, Bud Westmore, in molded latex. The studio’s elaborate 1943 remake starring Claude Rains had a long development period in which the Phantom’s backstory of congenital deformity was jettisoned in favor of acid mutilation as a plot point. The conceit was carried over to the second remake by Hammer Films in 1962, with Herbert Lom in the title role. Interestingly enough, in preparation for the Rains version, Universal considered making Erik a shell-shocked war veteran whose unmasking reveals a normal face, since his true disfigurement is from psychological trauma.

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 musical adaptation became the longest-running show in Broadway history, with total world receipts of $5.6 billion. A film version was released in 2004, with Gerard Butler in the title role. Universal never acquired stage rights of any kind to the Leroux book, and when it failed to renew the film’s copyright, which expired in 1953, the novel entered the public domain, where it continues to keep the Phantom’s legend alive.

If you enjoyed The Phantom of the Opera (1925), you might also like:

THE MAN WHO LAUGHS

UNIVERSAL PICTURES, 1928