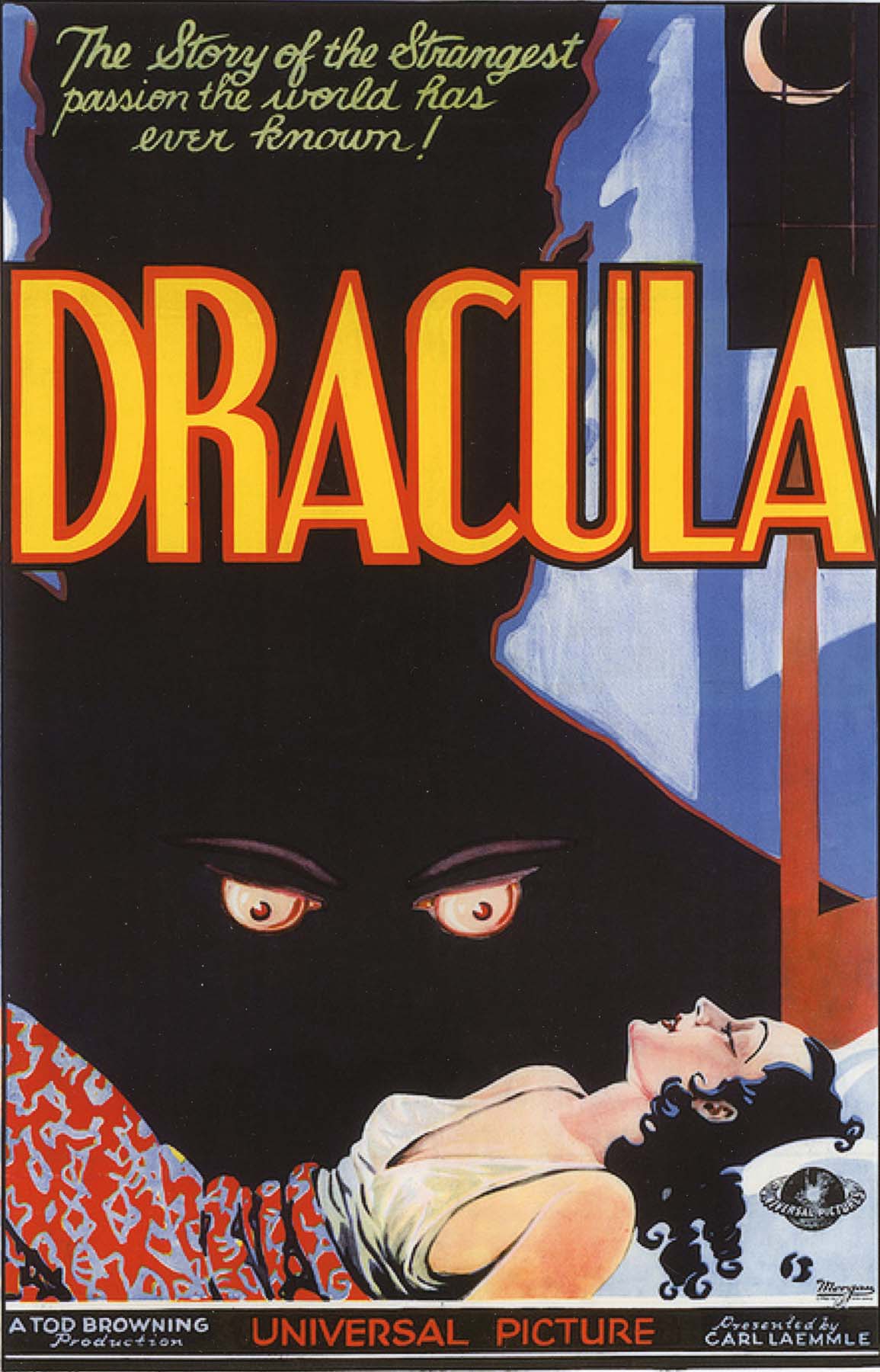

UNIVERSAL’S FIRST TALKING HORROR PICTURE, ABOUT A TRANSYLVANIAN SHAPE-SHIFTER, WAS ALSO A HOLLYWOOD GAME-CHANGER.

On February 12, 1931, a profound change occurred in American entertainment. All throughout the silent era, monstrous and frightening characters had been standard fixtures of the movies, but without exception they were presented as flesh-and-blood people, and any apparent manifestation of the supernatural always had a rational explanation, usually revolving around an elaborate criminal conspiracy. But as the lights came up at New York’s Roxy Theatre, the packed house must have been a bit dumbfounded at what they had just seen. In a short epilogue to the strange film, one of the actors stepped forth in front of a motion picture screen and attempted to reassure the audience. “When you get home tonight and you are afraid to look behind the curtains and you dread to see a face at the window… why, just pull yourself together and remember, after all—there are such things!”

Never before had American audiences been asked to accept a purely supernatural premise, and there was no guarantee of a positive response. Universal Pictures took quite a risk when it released Dracula on an unsuspecting public during the worst year of the Great Depression. Surely Depression audiences were interested in escapism, but did Dracula go too far?

The movie shocked audiences, but it also shocked the studio by upending box-office records everywhere it played, doing much to stabilize Universal’s shaky finances.

The studio had first considered Dracula for a silent film in 1915, the year of the studio’s founding. In 1920 an announcement was made that Dracula would be the next project for its up-and-coming director Tod Browning, a mystery specialist who had just begun collaborating with Lon Chaney. Universal’s silent Dracula was never realized, but both Browning and Chaney remained interested in the property throughout the 1920s.

Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) banishes the count with a repellent “more effective than wolfbane.”

In 1924, fresh from the copyright battle she had won over Nosferatu’s infringement of the novel, Stoker’s widow assigned dramatic rights to Hamilton Deane, an actor/manager with a large following in the English provinces. He pared down the sprawling book to the manageable dimensions of a drawing-room mystery-melodrama—and completely reworked the king of vampires from Stoker’s repulsive human leech into a far more palatable character, one who could plausibly be at home in polite company. It was Deane who gave Dracula evening clothes and an opera cape (with its trademark stand-up collar) and all the trappings that are today immediately associated with the character.

John L. Balderston, an American journalist and playwright based in London, was asked by New York producer Horace Liveright to adapt the play for Broadway, where it was a hit. Universal’s new production head, Carl Laemmle Jr., loved creepy movies, but he clashed with his father over the subject of horror films. Laemmle Sr. approved the purchase of Dracula with the proviso that the film would star the dependably bankable Lon Chaney and no one else. This proved impossible, but it was not until after the sale had been made that the Laemmles learned that Chaney was dying of lung cancer.

Tod Browning had been wooed away from Metro with the apparent understanding that Chaney would come with him. Bela Lugosi would seem to have been the next natural choice to star since the Hungarian actor had scored a considerable stage success in the part, but he was ultimately the last choice after a raft of actors, including John Wray, William Courtenay, Ian Keith, and Chester Morris, were considered. Today, of course, it is difficult to imagine anyone other than Lugosi in the film.

Browning, a self-taught master of silent direction, was not entirely comfortable with talkies, and the film’s long, soundless stretches suggest he is consciously or unconsciously shooting a silent feature. Despite his singularly distinctive voice, Lugosi’s dialogue is sparse, and he essentially gives a pantomime performance. Actor David Manners told this author that all his dialogue scenes were in fact directed by cameraman Karl Freund, whose moody, fluid cinematography is responsible for Dracula’s most distinctive sequences, especially the second reel, memorably shot on the massive, cobweb-festooned sets of Castle Dracula and including the film’s most memorable lines: “Listen to them—children of the night! What music they make!” and “I never drink… wine.”

Countess Zaleska (Gloria Holden) consigns her father’s corpse to the flames in Dracula’s Daughter.

Overall, the film roughly adhered to the outline of Stoker’s story: a five-hundred-year-old vampire leaves his desolate castle in Transylvania for the greater feeding opportunities afforded by modern London. He commandeers a ship that transports the earth boxes in which he must sleep by day, killing the crew and landing the vessel as a ghost ship on the English coast. He is assisted by a fly-eating madman, Renfield (Dwight Frye), and victimizes two women in turn: first Lucy (Frances Dade), who dies and becomes a vampire herself, and then her best friend, Mina Seward (Helen Chandler), whose father, John Seward (Herbert Bunston), operates an asylum where Renfield is a patient. When Mina begins to waste away under Dracula’s stealthy predation, a Dutch specialist in obscure diseases, Professor Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), is consulted. Van Helsing correctly identifies the vampire and pursues him to destruction. The oddest departure from Stoker is the downsizing of Mina’s fiancé and the book’s hero, Jonathan Harker (David Manners), to an ineffectual bystander. His trip to Transylvania to sell Dracula a London house is assigned to Renfield, who returns quite mad.

Bela Lugosi as Dracula, the role of his lifetime

Lupita Tovar and Carlos Villarías in the Spanish-language version of Dracula

Due to budgetary pressures, the latter portions of the movie dwindle to a filmed record of the stage play, though a simultaneously shot Spanish-language version, starring Lupita Tovar and Carlos Villarías, and directed by George Melford, was resourceful in finding ways to improve the staging and shooting of otherwise static scenes. Despite technical deficiencies, the bizarre novelty of the film led to strong box office everywhere. Universal, of course, was eager to produce a sequel, but the enforcement of the industry’s highly moralistic Production Code, beginning in 1934, almost immediately raised censorship issues and delayed the project. Aside from a quickly glimpsed wax effigy of Lugosi in a coffin and on a funeral pyre, Dracula himself didn’t appear in Dracula’s Daughter (1936).

Lugosi returned to the role at Universal in 1948 for the affectionate spoof Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Although audiences forever would associate him with the role he played in 1931, he only essayed the part twice on screen. His public identification with the role was so complete that, upon the actor’s death in 1956, his family requested that he be buried in full costume and makeup as Count Dracula.

If you enjoyed Dracula (1931), you might also like:

MARK OF THE VAMPIRE

MGM, 1935