A LEGENDARY TALE OF TERROR HAS ENJOYED THREE MAJOR HOLLYWOOD INCARNATIONS.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s hair-raising novella about dual identity, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, was first published in 1886, and after the great Victorian actor-manager Henry Irving declined to acquire the rights—some say foolishly—the story was successfully adapted for the stage by Richard Mansfield, an acclaimed American actor. Mansfield’s version, written in collaboration with Thomas Russell Sullivan, added two elements that would be crucial to film adaptations: female characters (Stevenson’s story was somewhat like a stuffy men’s club, told with male characters only) and special visual effects to aid Jekyll’s potion-fueled transformation into Hyde. Mansfield morphed himself into a monster in full view of the audience, using physical contortions and colored lights that could reveal and conceal correspondingly tinted makeup. Mansfield continued producing and starring in the play until 1904.

Several silent film versions were released in America and Europe beginning in 1908, the most notable being the 1920 Paramount production starring the legendary actor John Barrymore and directed by John S. Robertson. Barrymore achieved the transformation in a tour de force of contortions, covering his face with his hands in order to surreptitiously apply makeup, and adding claw-like extensions to his fingers. (It is entirely possible this last detail was noticed by Nosferatu’s art director, Albin Grau, who two years later would affix talons to the hands of actor Max Schreck for a similarly predatory look.) The Paramount film was an international sensation, exhibited widely in Germany and other European countries.

The beginning of Fredric March’s transformation sequence.

With the advent of sound, Paramount was eager to take advantage of the lucrative horror market being staked out by Universal, and in 1931 the studio asked Barrymore if he would repeat his acclaimed performance in a talkie. Barrymore, now a mature character actor and no longer the matinee idol that had made his Jekyll/Hyde transformation all the more startling, was perhaps no longer ideal, but he was unavailable in any event, having contracted with MGM. Paramount hired the Armenian-American film and theater director Rouben Mamoulian, who personally selected Fredric March to star. The previous year, March had received an Academy Award nomination for a role based directly on John Barrymore in The Royal Family of Broadway.

Fredric March, Rouben Mamoulian, and Miriam Hopkins take a tea break on the set.

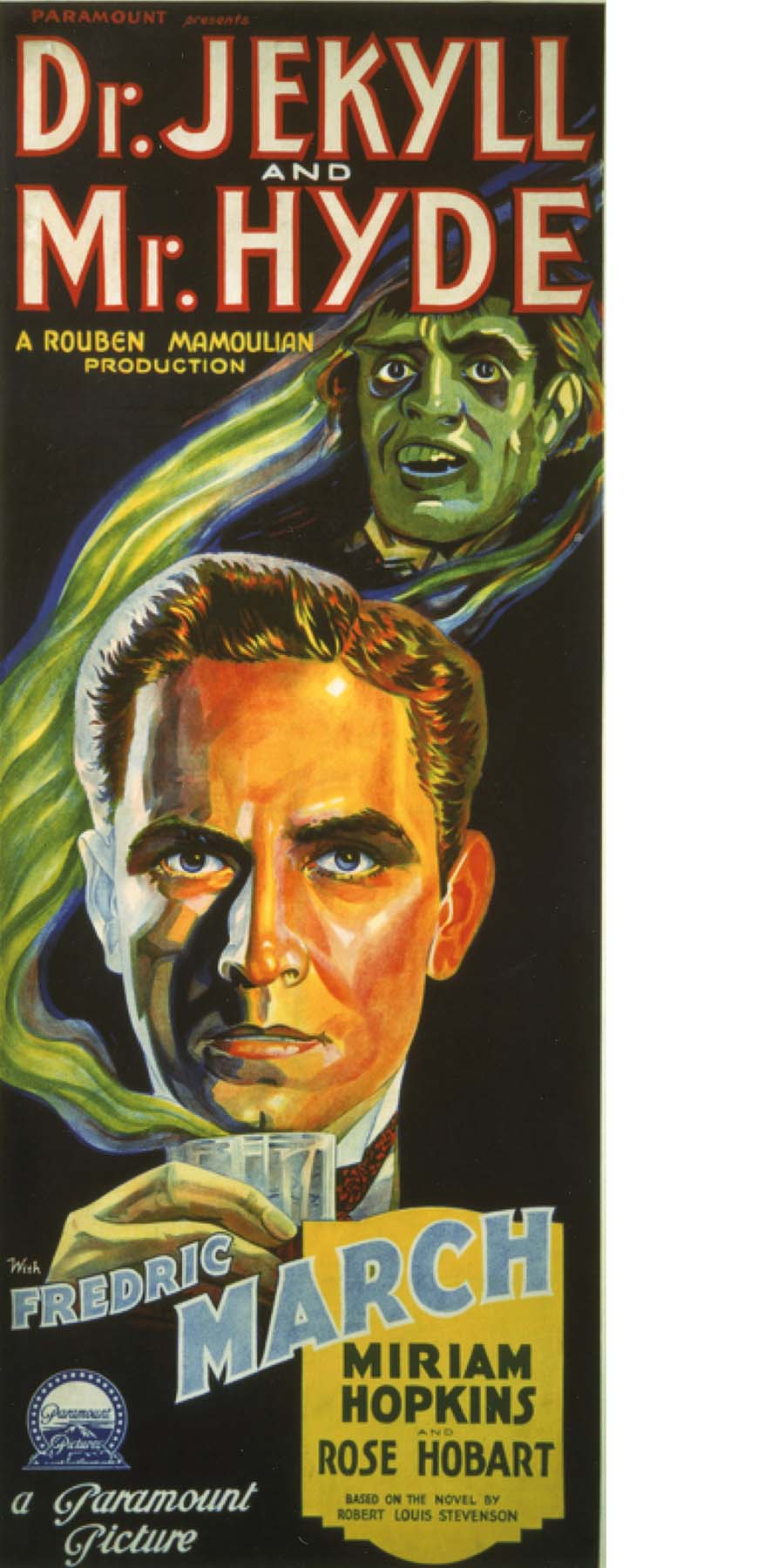

1931 poster for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Makeup artist Wally Westmore’s first tests seemed to draw inspiration from both Werner Krauss in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Lon Chaney’s costume and makeup from London After Midnight (1927). Previous dramatic interpretations of Hyde had been ugly, cruel, wicked, and thuggish—but still human. Mamoulian wanted his Hyde to be an animal. Ultimately, Westmore’s makeup devolved in stages, giving March a simian look that grew increasingly hideous with each transformation.

Mamoulian and cinematographer Karl Struss brilliantly adapted Richard Mansfield’s colored-light stage trickery for black-and-white film. Since the color filtering would be invisible on monochromatic film, the lines and contours of the “hidden” makeup seemed to emerge inexplicably from the actor’s skin. The ape-like facial appliances were even more unpleasant for March than Karloff’s headpiece and scars had been in Frankenstein. Glued directly to his skin, each progressive version became more and more difficult to remove, until, as March’s costar Rose Hobart remembered, his skin began to pull away along with the prosthetic, and the actor was hospitalized with facial abrasions.

Martha Mansfield and John Barrymore

Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins

In the 1920 film, Jekyll had a proper fiancée, and Hyde had a lower-class girl on the side, but he soon breaks off the dalliance. The 1931 screenplay, by Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath, brilliantly mirrors the Jekyll/Hyde duality with its female equivalents: Jekyll’s straitlaced fiancée (Hobart) and Hyde’s transgressive bar singer, Ivy Pearson, played by Miriam Hopkins as the quintessence of a pre-Code bad girl. Ivy’s increasingly violent and ultimately fatal entanglement with Jekyll’s alter ego is as raw and disturbing as the most harrowing accounts of domestic abuse. Especially chilling is the scene where she brazenly flirts with the good Dr. Jekyll, unaware she is inviting Mr. Hyde to come out to play. Eight minutes of cuts were demanded by the censors, even in a time of lax Code enforcement.

In 1941, MGM acquired all the rights to the Paramount film in order to produce a remake starring Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman as Ivy, and Lana Turner as the fiancée. The Mamoulian version was consigned to the MGM vaults for an exhibition embargo that would last for decades, much to the dismay of film historians. Tracy was eager to play Hyde as a man in the grip of alcohol or drugs, which made Jekyll’s transformation more psychological than physical. Tracy may well have been drawing on his own well-documented struggles with alcohol, just as many commentators have attributed the genesis of Stevenson’s story to the author’s periodic, uncontrollable drinking binges. The studio met Tracy halfway with the approach, retaining Stevenson’s original nonalcoholic elixir. Makeup artist Jack Dawn, who had created all the memorable characters for The Wizard of Oz, sharpened the actor’s natural features only slightly, allowing his acting to do the rest. Under Victor Fleming’s capable direction, Tracy’s performance is a truly horrifying portrait of unbridled malevolence and cruelty.

Spencer Tracy as Mr. Hyde

Because the story’s theme of the divided human spirit sounds so many universal chords, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is one of the most frequently dramatized works in the classic horror canon, the roles essayed on-screen by an endless succession of fine actors, including Louis Hayward, Christopher Lee, Jack Palance, and John Malkovich.

If you enjoyed Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), you might also like:

DR. JEKYLL AND SISTER HYDE

HAMMER/AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL, 1971