BURIED FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS IN A FORGOTTEN EGYPTIAN TOMB, AN UNDYING PASSION WALKS THE EARTH AGAIN.

John L. Balderston, the playwright responsible for the Dracula stage adaptation that was a major hit in New York, wasn’t entirely happy with Universal’s film. The last third “dropped badly,” he wrote. When Universal hired him to script the film ultimately to be known as The Mummy, he had the chance to incorporate and improve elements from the earlier film, and he drew also on his extensive knowledge of the opening of King Tutankhamen’s tomb, which he had covered firsthand a decade earlier for the New York World.

Balderston was given an existing screenplay called Cagliostro, by Nina Wilcox Putnam, which had already been announced, with some trade-magazine fanfare, as Boris Karloff’s next assignment. Cagliostro was a historical character, a seventeenth-century Parisian mountebank who convinced the rich and powerful that he had, somehow, lived for centuries. Universal liked the theme but not the script. It was Balderston’s idea to shift the focus to Egyptology, which had become a fashionable interest ever since Tut’s treasures were unearthed. The morbid details of Egyptian burial rites, as well as the public’s fascination with the curse of King Tut (completely contrived), were natural associations that upped the horror ante for an eagerly anticipated Karloff vehicle. Balderston’s most significant contribution was the reincarnation-of-a-lost-love motif, which has become a sturdy trope of supernatural horror movies, including most newer versions of Dracula.

An archeologist (Bramwell Fletcher) inadvertently brings the mummy to life.

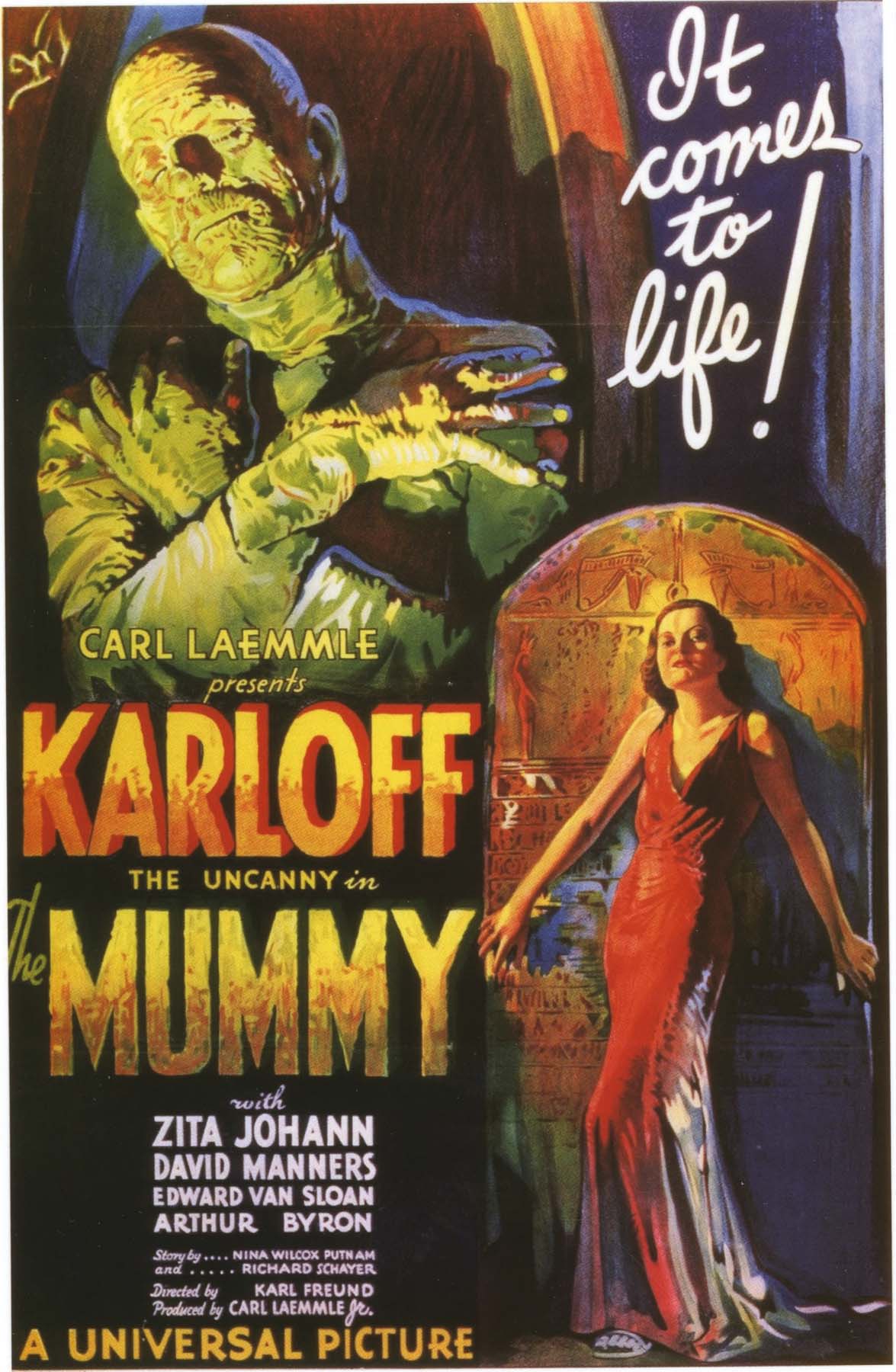

During preproduction, the project was alternately called Imhotep (after the actual Egyptian architect who built the pyramids but had no relation to the story) and King of the Dead. The studio had enough faith in Karloff’s rapidly ascending celebrity that it made the bold marketing decision to bill him solely by his last name—the sort of star treatment hitherto reserved for Garbo or Chaplin. The first actress considered for his leading lady was Katharine Hepburn, but when she proved unavailable the part went to the highly regarded New York stage actress Zita Johann. Making his directorial debut was cinematographer Karl Freund, reunited with two actors he had worked with on Dracula, Edward Van Sloan and David Manners, who essentially reprised their roles as the Wise Doctor and Worried Lover, respectively.

As it does in the previous film, the plot concerns an ancient, undead menace who returns from the dead to claim a modern bride. In an opening vignette, we witness the inadvertent midnight resurrection of Imhotep at an archeological dig. Ten years later, in Cairo, he is without bandages and partially rejuvenated, using the name Ardath Bey. He ingratiates himself into the good favor of the unsuspecting archeologists who reanimated him, leading them to the tomb of an Egyptian princess, Anck-es-en-Amon. They excavate the tomb for its treasures, which Bey donates to the Cairo Museum. He doesn’t tell them that the princess is his mummified lover, and that he has waited three thousand years to bring her back from the dead. His first attempt, in ancient Egypt, was a sacrilegious transgression that resulted in his being buried alive with the Scroll of Thoth, which has power over life and death. Bey meets a half-English, half-Egyptian woman, Helen Grosvenor, whom he immediately recognizes as the princess’s modern reincarnation. He intends to sacrifice her, rejoining her soul with the princess’s mummy, but his second attempted sacrilege is foiled by the goddess Isis, who incinerates the cursed scroll. Without it, Imhotep crumbles into bones and dust.

The scene that impresses most is the awakening of Imhotep, a brilliantly minimalist sequence that succeeds by showing almost nothing, especially when compared to the histrionic razzle-dazzle of the creation scene in Frankenstein. A young archeologist opens an ancient scroll and begins to read, not suspecting the forces he is about to unleash. The mummy’s eye cracks open, its arm moves slightly, and then, instead of a full reveal, we see only the bandaged hand reaching into the frame to claim the reanimating scroll. The archeologist goes mad, wildly laughing—“He went for a little walk… you should have seen his face!”—and the last signs we see of born-again Imhotep are a pair of trailing bandages as the undead thing shuffles out the door.

Edward Van Sloan, David Manners, Zita Johann, and Karl Freund on set

The preparation for ritual embalming

Zita Johann and Boris Karloff

Universal’s makeup wizard, Jack Pierce, once more subjected Karloff to a grueling ordeal, even more arduous than what the actor had endured for Frankenstein. Fortunately, he needed only wear the head-to-toe wrappings for a single day of shooting. For the rest of the filming days, Pierce wrinkled Karloff’s face far more subtly, using thin applications of spirit gum and tissue that furrowed his actual skin. Nonetheless, it all had to be removed each night with toxic solvents, an exceedingly unpleasant process.

In 1940, Universal embarked on a series of loosely connected sequels with The Mummy’s Hand. Tim Tyler played the mummy, now known as Kharis, but in the next film, The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), Lon Chaney Jr. took over the role—as well as the reputation of being Universal’s go-to monster man. During the war years he not only played the Mummy but additionally took on the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein monster, and Dracula’s son. He returned as Kharis in The Mummy’s Ghost and The Mummy’s Curse (both 1944). In 1955, for no discernible reason, the Mummy’s name was changed to “Klaris” for the comedy Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy. In 1959 Universal distributed the Hammer Films remake, starring Christopher Lee, and in 1999 restored the name “Imhotep” for Stephen Sommers’s The Mummy, which became a successful mini franchise that included The Mummy Returns (2001) and The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008). Brendan Fraser starred in all three films. In 2017, Universal resurrected The Mummy yet again, turning the tables by serving up a female mummy with malignant designs on Tom Cruise. The film was intended to be the inaugural component of a branding initiative called Dark Universe that would reboot and recombine the Universal monsters in a superhero-like franchise. No second film has yet materialized.

Karloff as the semirejuvenated Ardath Bey

If you enjoyed The Mummy (1932), you might also like:

THE AWAKENING

ORION PICTURES, 1980