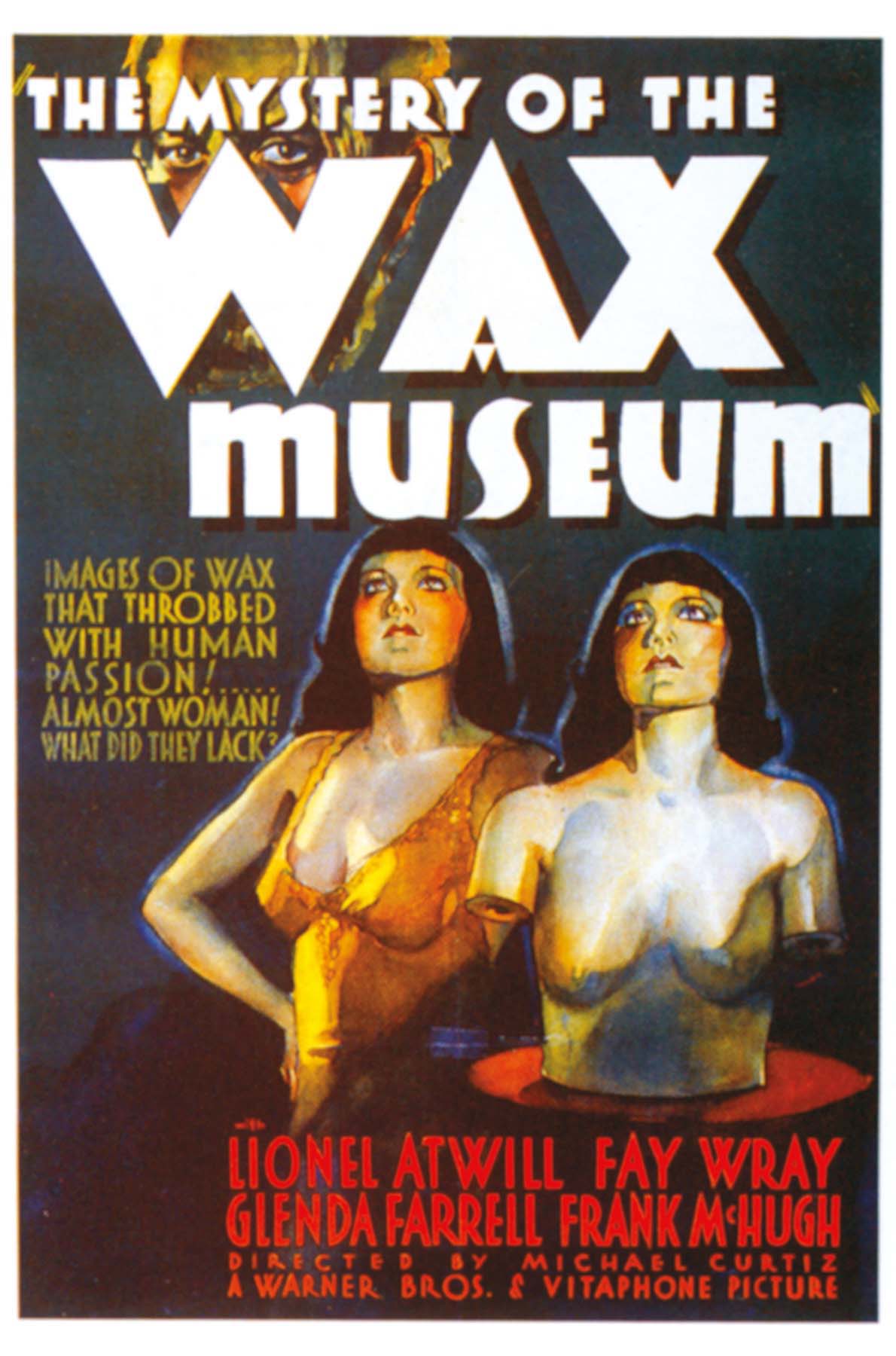

HIS VICTIMS DIED… BUT HE PRESERVED THEIR BEAUTY FOREVER IN WAX.

There is a good reason that doubles, dolls, and effigies of all kinds figure prominently in horror stories. According to psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud and Otto Rank, perfect human simulacra, or doppelgängers, arise spontaneously in the primal imagination as defense mechanisms against danger and death. If one self is killed, the other will survive. Motion pictures are another way to create duplicate people that originally had a palpably creepy edge. Some early commentators on the medium worried that film might be nothing less than the arrival of living death. It is in horror movies that this pervading sense of the uncanny still speaks to us.

Before movies, people went to wax museums to experience a pleasurable shudder in the presence of human replicas. The main attraction was often a Chamber of Horrors that re-created historical atrocities as well as tabloid tableaux of gruesome modern crimes. The world’s most famous wax museum was Madame Tussaud’s in London, which made headlines in 1925 when it was spectacularly destroyed by fire. The incident stuck in the mind of one playwright, Charles S. Belden, author of an unproduced play called The Wax Museum, in which he imagined a sculptor named Ivan Igor who survives a similar conflagration hideously disfigured and mentally unhinged. He rebuilds his exhibit with embalmed corpses coated in wax.

Warner Bros. acquired the rights to the play at the height of Hollywood’s 1931–1932 lucrative “monsterfication,” led by Universal. Paramount had already scored considerable success with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Island of Lost Souls, while MGM had failed to capitalize on the horror craze with Tod Browning’s gamble, Freaks, which backfired badly, repelling audiences and critics with its display of real human deformity. But on the whole, horror still seemed a good bet. Warners produced Doctor X, based on a hit Broadway horror play, casting Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray, and Arthur Edmund Carewe. The formula performed well enough at the box office that the same actors were immediately assigned to Mystery of the Wax Museum.

Lionel Atwill as Ivan Igor

Both films were shot in two-strip Technicolor, a film process that effectively suggested a full-color image without actually requiring that one be entirely created (a similar, cost-saving process was already well-established in magazine illustration and printing). The heightened realism worked the same magic on audiences as did wax figures—the more lifelike the illusion, the more riveting it became.

The film opens in 1921 London. Ivan Igor (Atwill) is a talented waxworks artist committed to elevating his craft into a respected art form, but his museum is failing badly because he refuses to pander to public taste by installing the obligatory horror exhibits. His business partner sets fire to the premises to collect insurance money, leaving the sculptor to die in the flames. But Igor somehow survives, now in a wheelchair, and twelve years later he reappears in New York City with a new exhibit, this one calibrated to appeal to morbid popular taste with scenes of murder, torture, and execution. When he meets Charlotte Duncan (Wray), the girlfriend of his studio assistant, he immediately sees the image of his most beloved lost creation, a statue of Marie Antoinette, and becomes obsessed with her. Charlotte’s roommate, Florence Dempsey (Glenda Farrell), a wisecracking reporter, notices that Igor’s sculpture of Joan of Arc bears a startling resemblance to another woman named Joan—a recent suicide whose body was stolen from the morgue—and starts to smell a story.