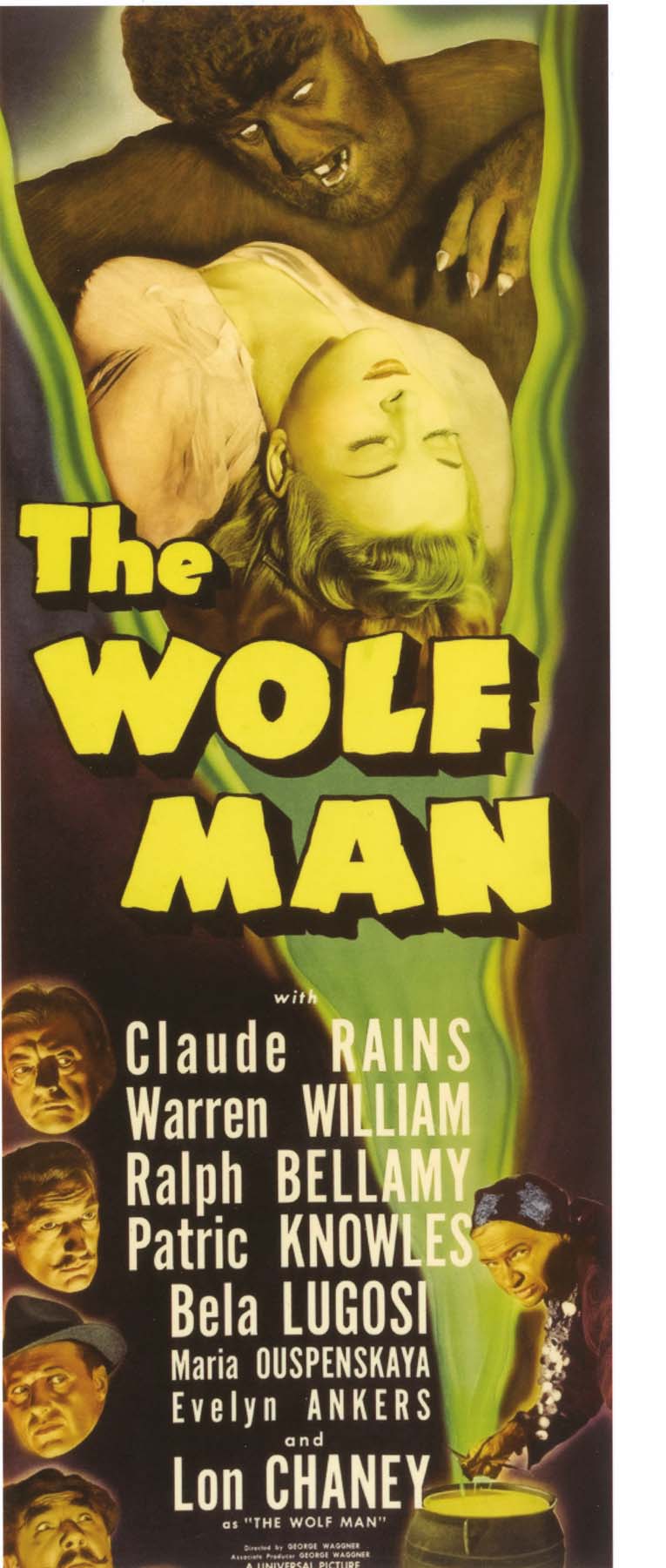

HOLLYWOOD DISCOVERS ITS MOST FAMOUS BEAST WITHIN.

Universal’s The Wolf Man, ten years in the planning, was originally intended as a vehicle for Boris Karloff, to follow the enormous success of Frankenstein. Filmmaker Robert Florey, who had first been slated to direct Frankenstein from his own script, would next direct Murders in the Rue Morgue while simultaneously developing a story treatment called The Wolf Man. The story had strong expressionist flourishes and was certainly screen worthy, but the studio feared religious objections, especially to a scene depicting a werewolf transformation that took place not merely in a church, but inside a confessional. The Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles had given Universal considerable grief over Frankenstein, prompting the studio to add a prologue underscoring the point that the film was cautionary and in no way encouraged acts of divine presumption.

The studio finally tangled with lycanthropy in Werewolf of London (1935), and once more, censorship considerations forced changes in the film. Jack Pierce created the now familiar Lon Chaney makeup for Werewolf star Henry Hull, but Joseph Breen of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, the new chief enforcer of the Production Code, warned Universal not to use “repulsive or horrifying physical details” or “the actual transvection from man to wolf.” In the end, Hull wore a minimally disguising, almost feline makeup. The film disappointed at the box office.

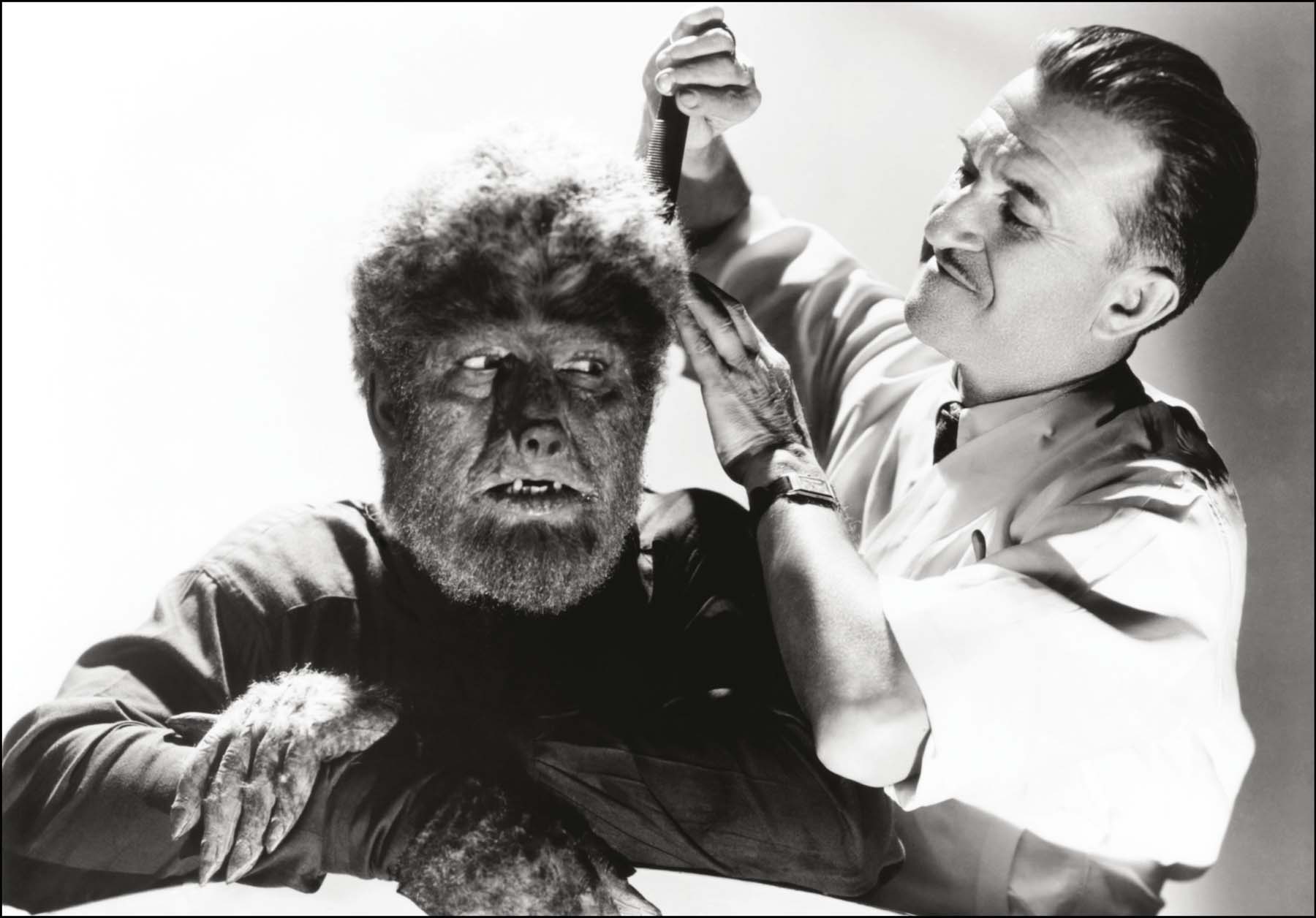

Makeup artist Jack Pierce puts the final touches on Lon Chaney Jr.

The same year, Lon Chaney Jr. became the professional pseudonym (very reluctantly adopted) by the elder Chaney’s actor son, Creighton, under pressure from agents and producers to capitalize on a stellar Hollywood name. Afterward, his casting fortunes decidedly improved, and in 1939 he received a well-deserved supporting-actor Academy Award nomination for the role of Lenny, a mentally challenged ranch hand who is unaware of his own strength, for United Artists in Of Mice and Men. Lenny unintentionally kills a young woman, sealing his own fate, a plot element that echoed one of the most famous and pathos-filled scenes in Frankenstein. Studios hadn’t previously imagined the younger Chaney in monster parts, but the character of Lenny, with his frightening brute strength, shared a decidedly similar casting category. Chaney Jr. tested for RKO’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, another prestige film, and was provisionally offered the part when it seemed that Charles Laughton, a British citizen, might be unavailable because of foreign tax problems with the IRS. But the issue was settled, and Laughton played the part.

Universal didn’t have prestige roles for Chaney Jr., but it could offer him steady work in its horror programmers. He played the robotic title role in Man Made Monster (1941), still billed as “Jr.,” but was finally able to shed the qualifying suffix later the same year for The Wolf Man.

The only thing left from the 1931 Florey treatment was the title; German expatriate screenwriter Curt Siodmak was entrusted with concocting a believable European werewolf mythology. He was so successful that people often mistake the “gypsy poem” he wrote as a relic of actual folklore:

EVEN A MAN WHO IS PURE IN HEART

AND SAYS HIS PRAYERS BY NIGHT

MAY BECOME A WOLF WHEN THE WOLFBANE BLOOMS

AND THE AUTUMN MOON IS BRIGHT.

Lon Chaney Jr. and Maria Ouspenskaya

Surprisingly, the full moon is never mentioned, or even shown, anywhere in The Wolf Man. The gypsy’s verse refers only to a bright autumn moon, and nothing of its phases. Werewolf legends date to antiquity, and only in some traditions is a full moon required; many werewolves have the power to transform at will in much of the mythology.

In the story, Lawrence “Larry” Talbot (Chaney Jr.), Welsh born but American raised, returns to his family’s ancestral estate to reconcile with his estranged father, Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains). He becomes romantically attracted to a local shopkeeper, Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers), and accompanies her and a friend, Jenny, to a Romany fair, where Jenny has her palm read by a gypsy named Bela (Bela Lugosi). Bela sees the shape of a pentagram in Jenny’s hand and immediately warns her to leave. She flees, but not before Bela turns into a wolf and pursues her to a grisly end. Larry struggles with the wolf, killing it with a walking stick bearing a silver wolf’s-head handle. But the animal wounds Larry in the chest, upon which a foreboding star appears. Bela’s mother, Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya), explains to Larry that he is now cursed, just as her son was cursed. The story moves with the relentless momentum of a Greek tragedy as Larry, gripped by his fate, is transformed into a half man/half wolf and commits a series of murders. In the end he attacks Gwen, but he is killed by his father with the same silver-headed cane he used to kill the gypsy woman’s son.

Lon Chaney Jr. and Evelyn Ankers

Curt Siodmak was himself a Dresden-born Jew who had fled the rise of Hitler and knew full well the portent of the pentagram and how the sign of a star could brand one for death. Additionally, the wolf was an ancient Teutonic symbol of war, fully embraced by the Nazis, many of whom also embraced occultism. Under George Waggner’s direction, and the moody cinematography by Joseph Valentine, war metaphors took a backseat to top-notch turns by an impressive roster of stars, especially Chaney Jr., whose convincingly tormented performance has often been attributed to his own private demons.

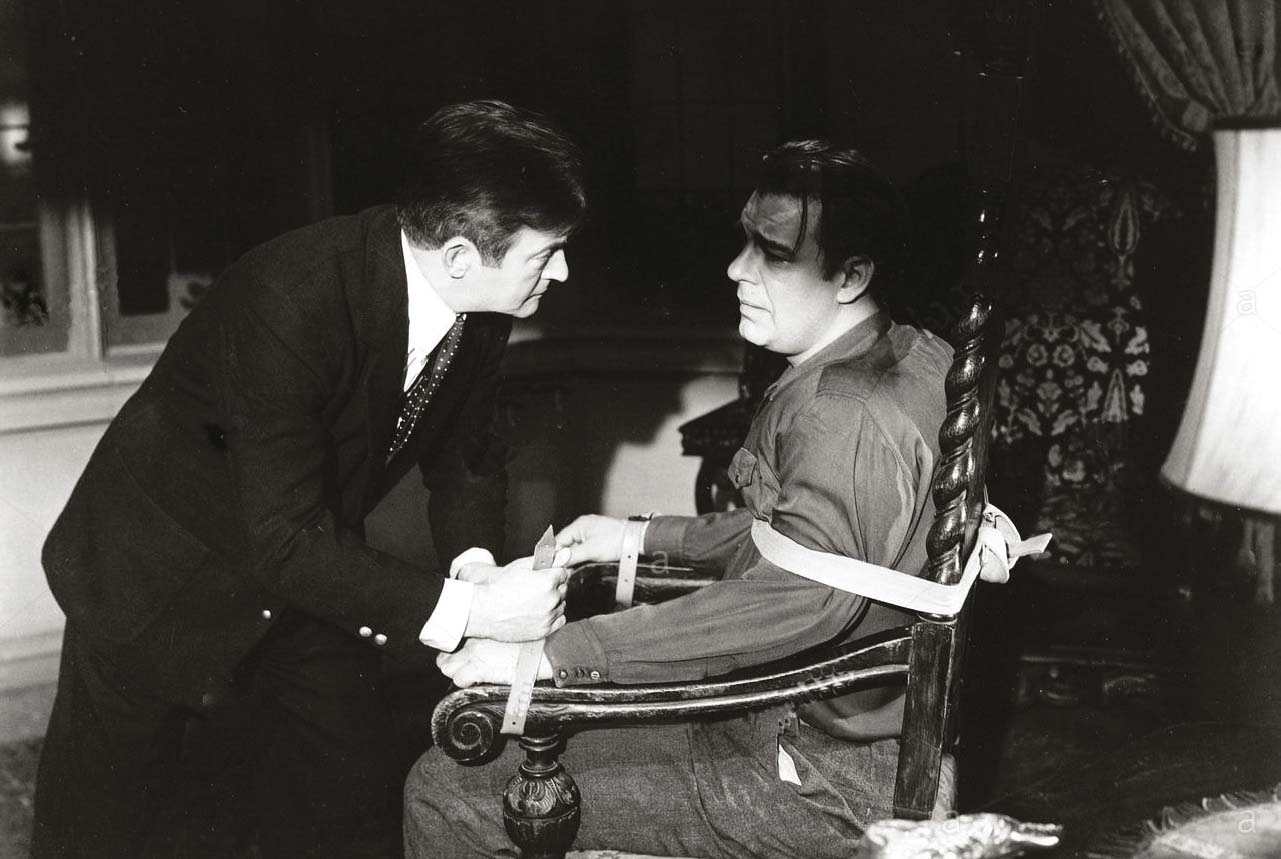

Claude Rains and Lon Chaney Jr.

The character of the Wolf Man was unique among the Universal monsters in being played by only one actor over the course of five films, with no consideration of recasting. Chaney Jr. returned to the role in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). In all these films, a full moon is essential to bring forth the beast within, and the reference to the moon in the gypsy’s poem is officially changed from “when the autumn moon is bright” to “when the moon is full and bright” whenever the lines are recited.

If you enjoyed The Wolf Man (1941), you might also like:

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON

POLYGRAM PICTURES, 1981