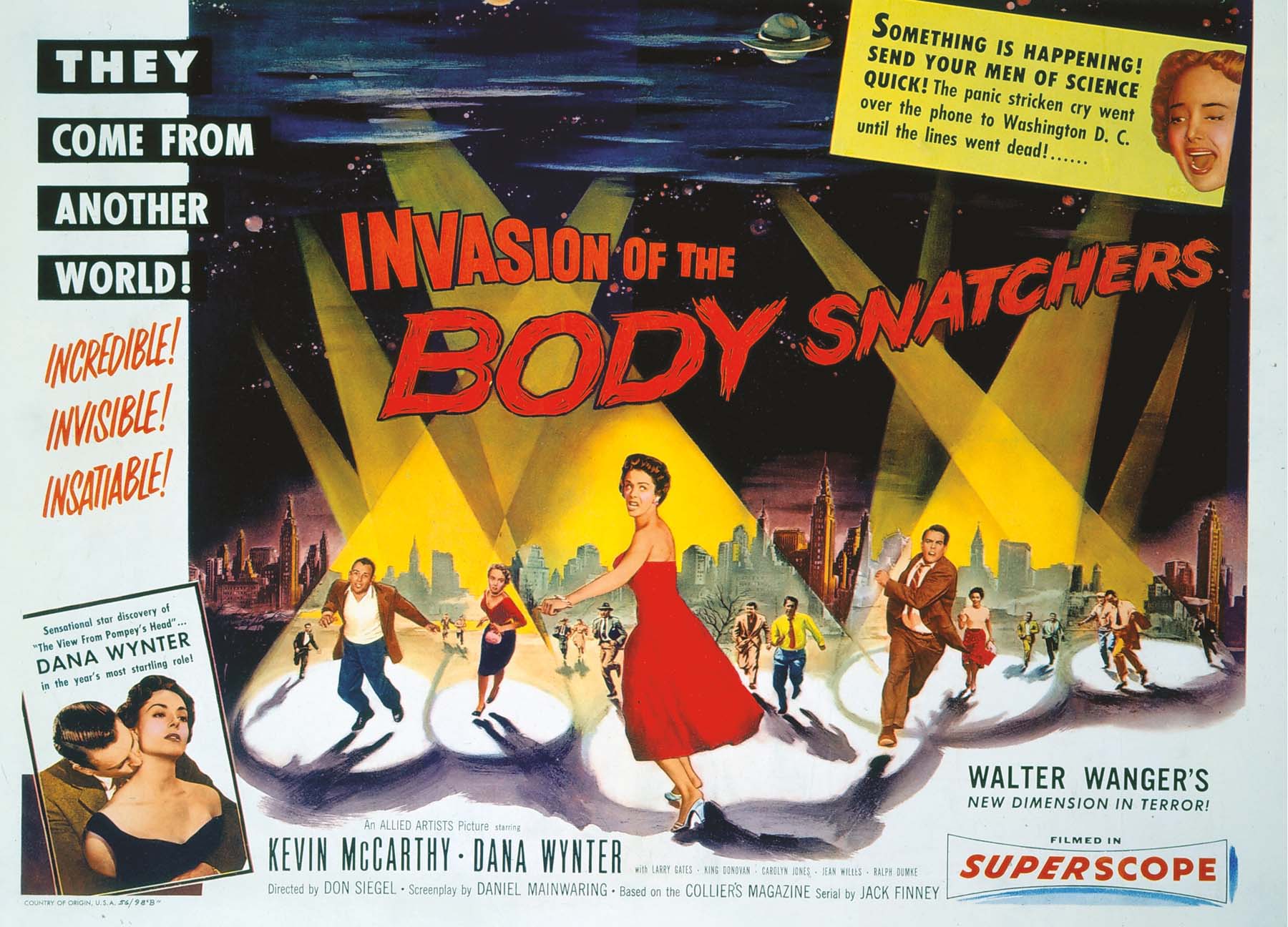

THE SCI-FI CLASSIC THAT BROUGHT TOGETHER PODS AND MONSTERS.

In the emergency room of a hospital in the town of Santa Mira, California, a man seemingly driven mad by a traumatic experience he can barely describe finally calms down sufficiently to tell his story to an attending psychiatrist. The man identifies himself as Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy), a family practitioner who recently began seeing patients suffering from the same delusion—that their loved ones are being mysteriously replaced by identical, living replicas. He meets a former girlfriend, Becky Driscoll (Dana Wynter). Both are recently divorced, and a rekindled relationship seems likely. But the epidemic of supposed imposters creates a distraction.

Miles’s friend Jack Belicec (King Donovan) and his wife, Teddy (Carolyn Jones), are disturbed by the mysterious appearance on their rec-room pool table of a not exactly dead, yet not exactly living, humanoid form. It seems to be a precise replica of Jack, though incompletely developed. A similar body that looks like Becky is found in her basement, and soon all four characters find more duplicates of themselves emerging from giant seedpods that have been placed in Miles’s greenhouse. They realize that the pods are the source of the townsfolk’s obsession with “replacement” friends and family members. The population is indeed being rapidly duplicated by emotionless alien doppelgängers who plan to impose a universal, tranquilized conformity on the human race. As one of the pod people explains, “Your new bodies are growing in there. They’re taking you over, cell for cell, atom for atom. There’s no pain. Suddenly, while you’re asleep, they’ll absorb your mind, your memories… and you’re reborn into an untroubled world.”

King Donovan (with pitchfork), Dana Wynter, Carolyn Jones, and Kevin McCarthy search for alien pods hidden in a greenhouse.

Based on a magazine serial by Jack Finney (later published as a novel), Invasion of the Body Snatchers is often described as a Red Scare allegory, but in truth it is a much more subtle exploration of the pervasive feeling in 1950s America that the world after the war had fundamentally changed, making everyone question common assumptions about American identity. Communism, of course, had long been painted as a soulless juggernaut that threatened to crush individualism. But many features of midcentury American life were also deemed as dehumanizing. The mass exodus to the suburbs and their assembly-line housing developments left many people alienated and adrift in a strange new land that valued blind materialism and social conformity over all else. More and more, Americans didn’t know their neighbors. Who knew what they might really be? During the Korean War, frightening stories of American prisoners being brainwashed were widely reported in the media, driving home the idea that selfhood and identity were unstable and malleable. In the 1950s, prescription tranquilizers were the fastest-growing category of pharmaceuticals, a ready gateway to the “untroubled world” described by the body snatchers.

Don Siegel himself once told an interviewer that he was not presenting a political allegory, but rather expressing his own jaded, if not downright bleak, assessment of society—namely, that “the majority of people unfortunately are pods, existing without any intellectual pretensions and incapable of love.” And it is just such a downbeat worldview that colors the film’s chilling climax, when Miles kisses the sleep-deprived Becky, and she looks upon him with eyes that are, suddenly, not of this Earth.

Siegel was known for films with naturalistic performances shot on location, a far cry from the typical studio-bound sci-fi of the period. Both Siegel and producer Walter Wanger were eager to create something more ambitious than just another alien invader film, and they succeeded. In Daniel Mainwaring’s intelligent, well-crafted script, Miles and Becky are believable and appealing characters with interesting backstories; we become invested in their lives immediately. Although almost the entire film was shot on location, as the story progresses the vérité aspects give way to more controlled, stylized compositions with an almost expressionistic use of light and shadow. No attempt is made to render the fantastic invasion rationally comprehensible. For example, the exact physical process of alien body replacement is never really clarified, making it all the more distressing and disorienting when it happens. Does the new body come to life and physically dispose of the old one? Is the victim possessed by a kind of mental projection? Or do both bodies somehow merge into a single organism? None of these questions are answered, or even addressed. As a result, the film is all the more frightening.

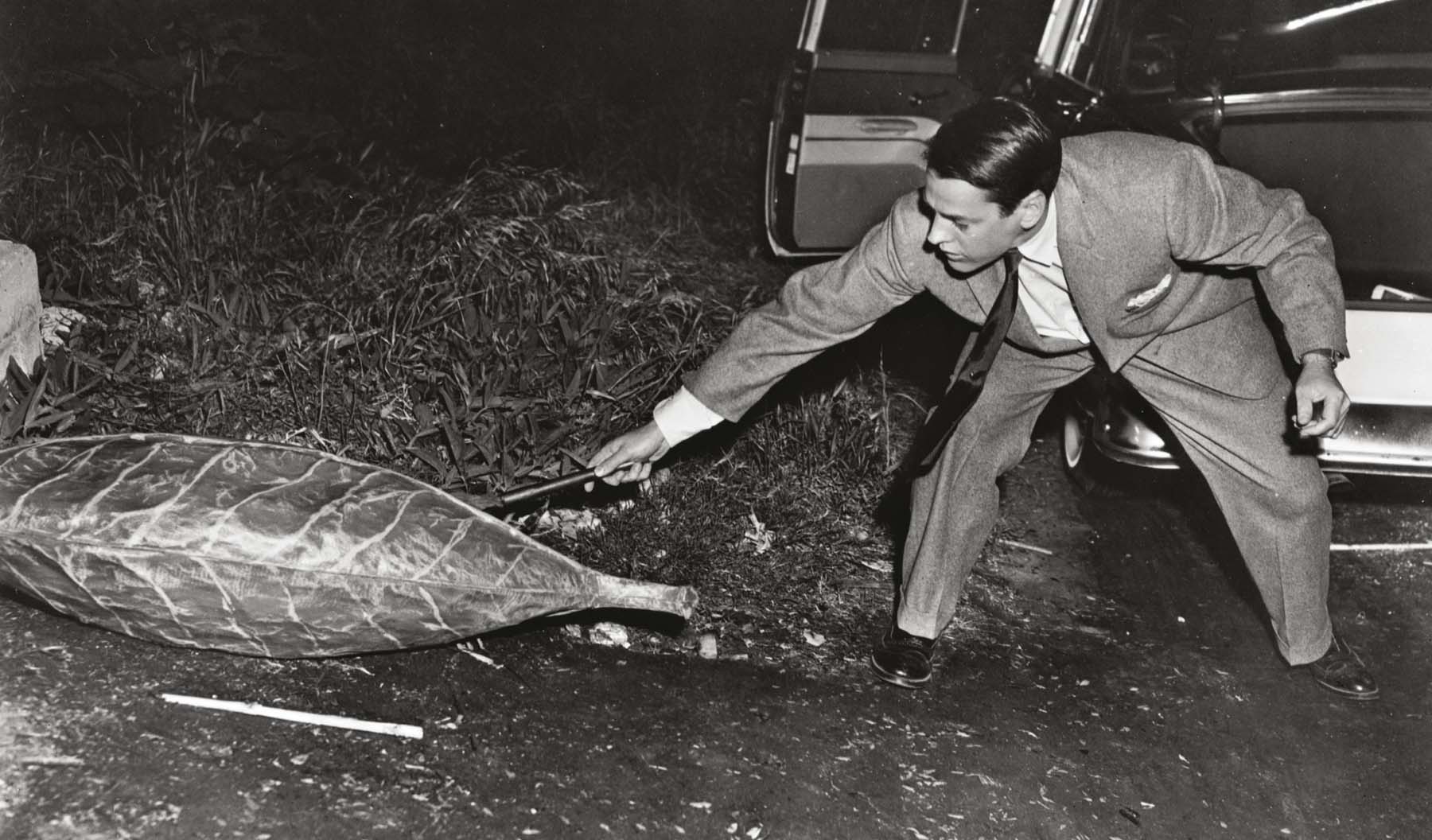

Miles sets fire to one of the pods.

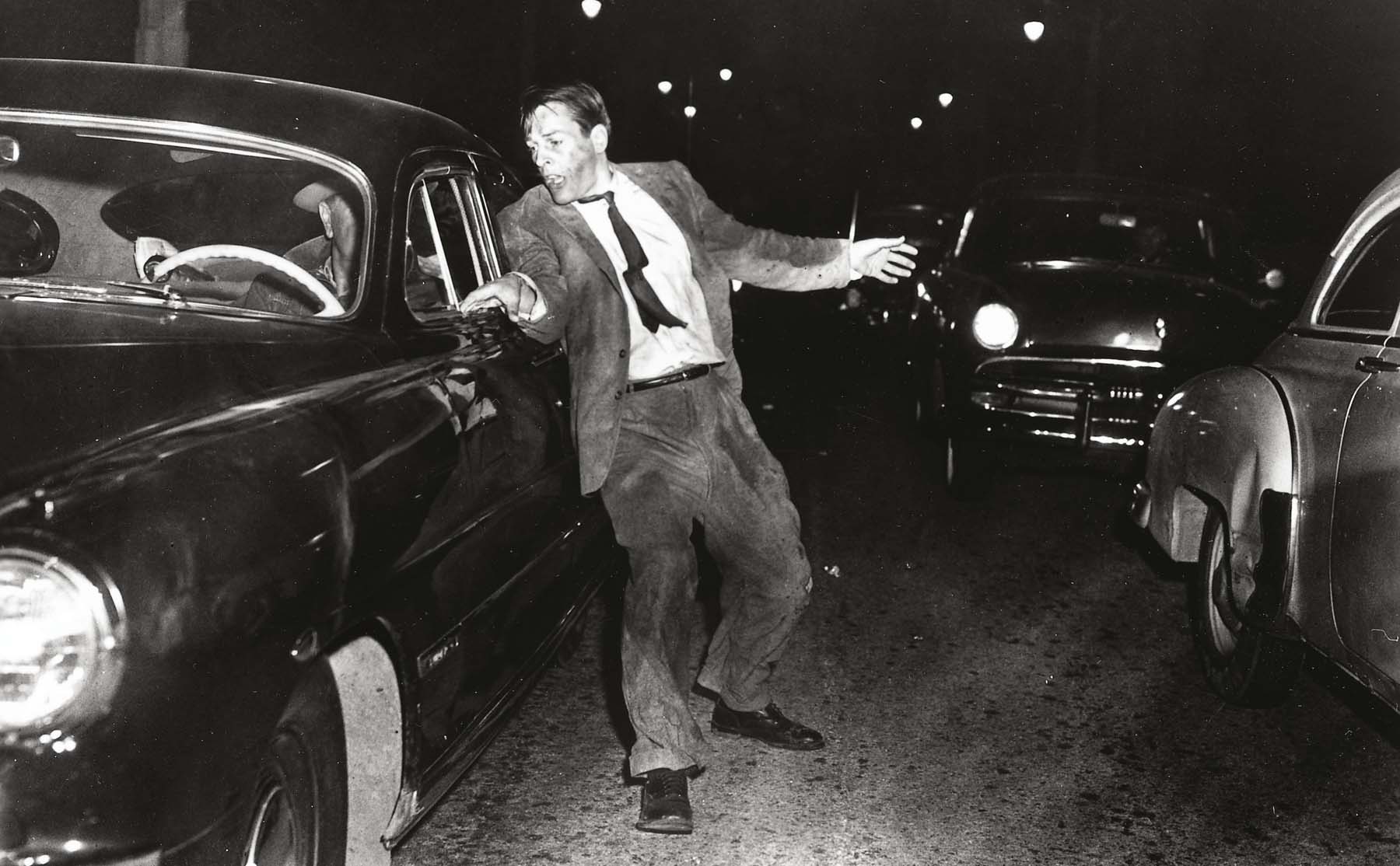

The hospital prologue and a bookend epilogue were added at the studio’s insistence, six months after principal photography had wrapped. A preview audience’s reaction reinforced the studio’s opinion that the film was just too much of a nightmare with its dizzying final scene of Miles stopping cars in the Cahuenga Pass, warning, “They’re here! You’re next!” Neither Wanger nor Siegel was pleased with the device, in which the car-stopping scene dissolves back to the emergency room, where another patient arrives, confirming Miles’s wild tale, and someone finally calls the FBI.

No one originally involved with the film liked the title—the only decent alternate suggested was Sleep No More—but the picture is now so deeply embedded as an artifact of popular culture that it’s hard to imagine it being called anything but Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Even people who have never seen the film have a pretty good idea of what a “pod person” is.

Miles examines a strange simulacrum of his friend Jack that has materialized on his pool table.

Miles makes an unnerving discovery in Becky’s basement.

Miles stops traffic, trying to warn the world.

If you enjoyed Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), you might also like:

INVADERS FROM MARS

20TH CENTURY FOX, 1953