THE FILM THAT RAISED A NEGLECTED GENRE FROM THE DEAD.

In Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994), an out-of-work Bela Lugosi (Martin Landau, in an Academy Award–winning performance) bemoans the decline of classic horror in the postwar era. “Nobody wants vampires anymore. Now all they want is giant bugs!” This was indeed the case at the time, and Lugosi didn’t live to see the international revival of gothic cinema that would begin only three months after his death. Hammer Films in England began production in November 1956 on The Curse of Frankenstein, the first straightforward screen adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel since 1931.

Using visceral, instead of electrical, shocks, The Curse of Frankenstein jolted a dormant genre back to unstoppable life. Nineteen fifty-seven was a highly consequential year for scary movies. The “big bug” formula was reaching a saturation point on American screens, and Universal was simultaneously releasing its classic chillers to television for the first time. An exponentially larger audience than had ever seen the original films in theaters was having its first exposure to an older form of frightening entertainment, and was highly receptive to it.

Hammer, a long-established British studio known for its low-budget thrillers, received stern admonishments from lawyers at Universal that it could not copy Universal’s classic film in any way, especially Boris Karloff’s iconic portrayal and his distinctive makeup. Since Shelley’s novel had been published in 1818, the story was safely in the public domain; anyone was free to adapt it to the screen. In deference to Universal, whose original Frankenstein was a key attraction of its Shock Theatre television package, Hammer augmented its title to avoid any confusion.

Victor watches the Creature taking its first steps.

The Curse of Frankenstein was writer Jimmy Sangster’s third produced screenplay, but his background in production management prepared him well to transform a sprawling novel into a cost-effective chamber piece. To achieve a lush period look, the production department pushed its ingenuity and resourcefulness and took full advantage of the access it had to Bray Studio’s huge store of nineteenth-century costumes, antiques, props, and recycled set pieces. More often than not, a thrown-together assemblage of furniture looked true to life and historical.

Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing), a child prodigy born into a wealthy Swiss family, grows into more than the equal of his tutor, Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), and the two men become research partners, delving deeply into the mysteries of life and death. After one of their experiments succeeds in reviving a dead puppy, Victor becomes obsessed with bringing to life an ideal human being assembled from the choicest parts of corpses—the hands of a great pianist, perhaps, or possibly the brain of a genius. Unknown to Paul, he invites a distinguished old professor as a houseguest, then kills him for his superior brain. Paul is horrified when he learns the truth about the professor’s “accident,” and in an ensuing struggle in Victor’s laboratory, the brain is damaged, but Victor persists in his quest to play God. They bring the patchwork body to life, but far from being a perfect specimen, the creation is a shambling travesty of a human being, clearly brain damaged, its face a mass of scar tissue. The monster (Christopher Lee) escapes into the woods, killing a blind man and his grandson. Paul and Victor give chase, Paul shoots the creature in the head, and they bury the thing in the forest.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth (Hazel Court), Victor’s fiancée by family arrangement since childhood, comes to live with him after her guardian dies. She is eager to plan their wedding. But Victor is distracted by a tawdry affair he is pursuing with his maid, Justine (Valerie Gaunt), and in any case is too self-preoccupied to comprehend the concerns and feelings of others. Victor has surreptitiously dug up the monster and restored it to life. When Justine poses a threat to the marriage by claiming she is pregnant, it is a simple matter to silence her with the monster, but Victor’s transgressions against God and nature are not so easily resolved.

With The Curse of Frankenstein, Hammer introduced the formula that would serve it well through the next two decades: in addition to the trademark presences of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, there were gothic horror, explicit gore, and generous helpings of sex. Skirmishes with the British Board of Film Censors became a cat-and-mouse ritual as the studio reveled in its transgressions against propriety and taste. The critics were uniformly aghast. Among the many images in The Curse of Frankenstein that raised objections were a close-up of severed hands, a freshly disembodied eyeball seen through a magnifying glass, blood welling up from a shotgun wound to a head, and other pleasantries. Compared to today’s gorefest standards, these effects are actually quite restrained, but at the time they were radical departures from accepted screen decorum.

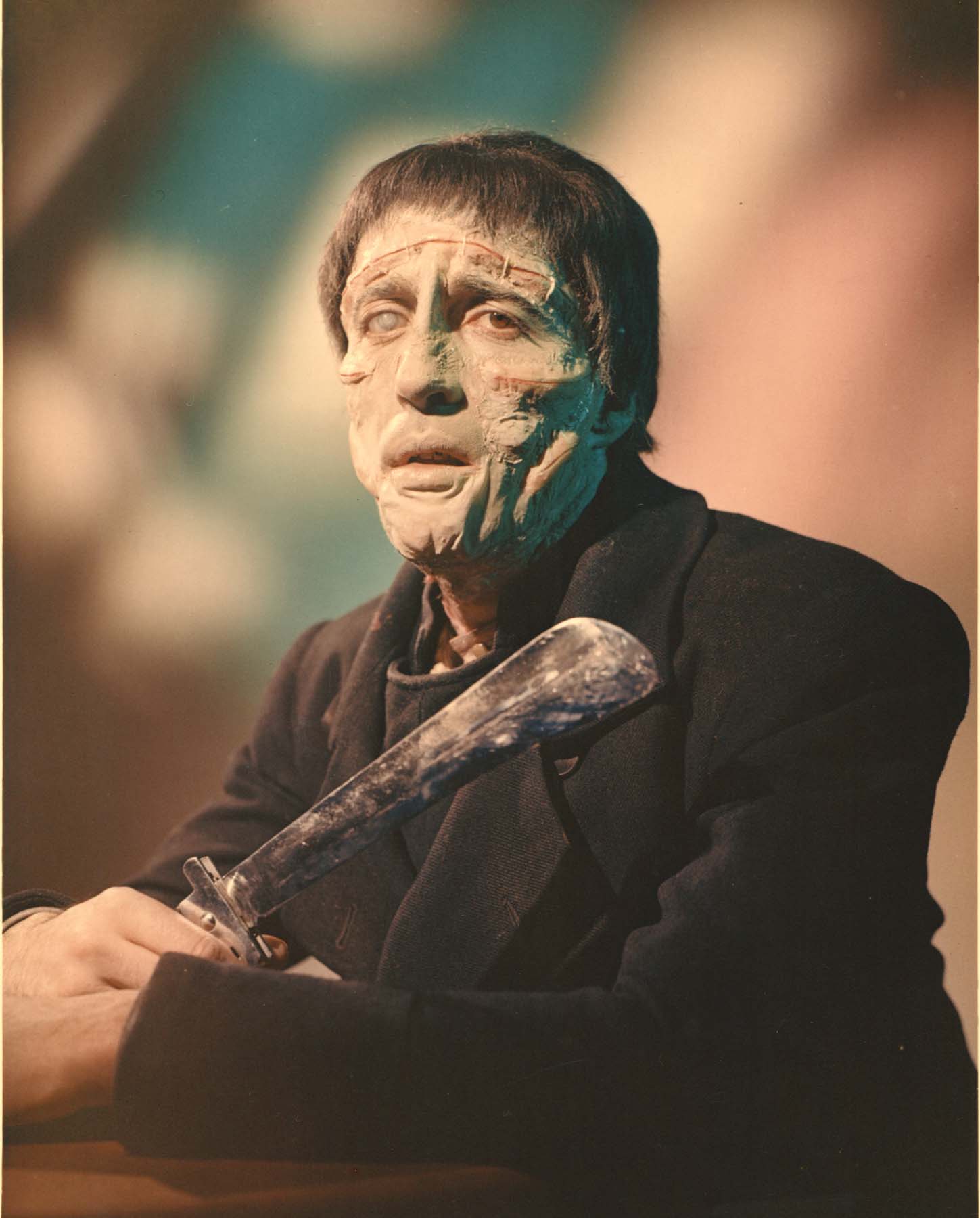

Christopher Lee as the Creature

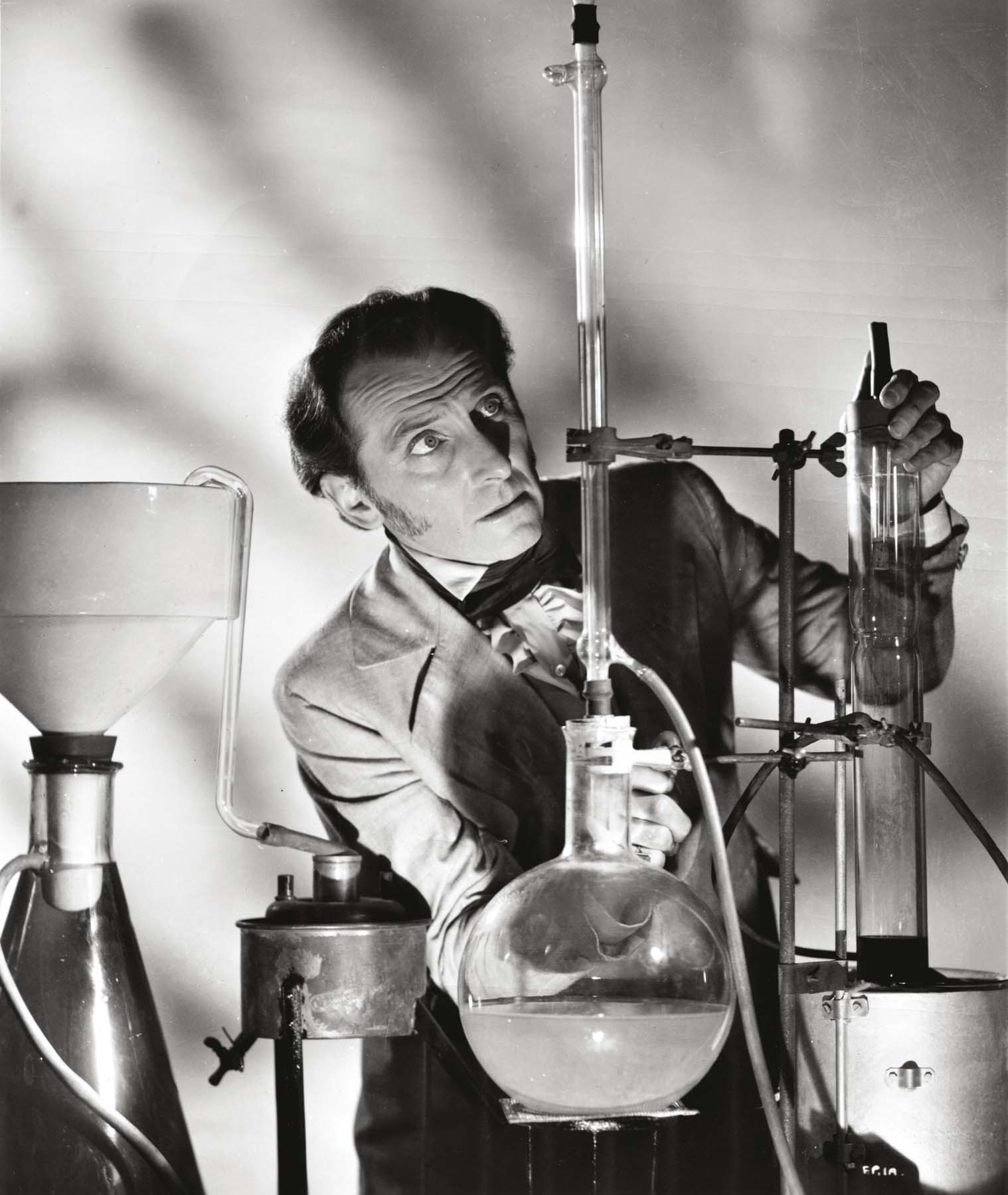

Peter Cushing as Victor Frankenstein

Hammer produced six sequels starring Peter Cushing, including The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974). Another film in the series, The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), featuring Ralph Bates as Victor, is generally considered to be an undistinguished misfire and a completely unnecessary attempt to remake the original film.

Paul (Robert Urquhart) warns Elizabeth (Hazel Court) of Victor’s madness.

Elizabeth recklessly enters Victor’s secret domain.

If you enjoyed The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), you might also like:

MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN

TRISTAR PICTURES, 1994