EDGAR ALLAN POE, SWINGING WITH THE SIXTIES.

Film studios have long understood that the name Edgar Allan Poe has considerable marquee potential, but finding a way to adapt Poe’s singular sensibility to the screen has always been problematic. Although he could plot a good detective story (and is often credited with having invented the genre), Poe’s most famous tales tend to be claustrophobic mood pieces. In 1960, Roger Corman enlisted Richard Matheson to script House of Usher, the first in a series of highly successful Poe adaptations starring Vincent Price. Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” had a conventional story arc that didn’t need much padding to work as a screenplay. “The Pit and the Pendulum,” however, centered on a single, nameless character trapped in a harrowing but essentially static situation. Price’s daughter and biographer Victoria Price quoted Matheson at first calling the challenge “ridiculous… we took a little short story about a guy lying on a table with this huge razor-sharp blade swinging over him, and had to make a whole story out of it.” A viable script would need to build an outside world, and its inhabitants as well. Fortunately, Richard Matheson was a writer thoroughly up to the task.

Francis Barnard (John Kerr) is an English gentleman of the sixteenth century visiting Spain to clarify the details of the unexpected and unexplained death of his sister Elizabeth (Barbara Steele), who was briefly married to Don Nicholas Medina (Vincent Price). The don’s father, Sebastian, was a notorious participant in the Spanish Inquisition, and the family’s castle retains all the infamous instruments of torture. Nicholas offers evasive and unconvincing reasons for his wife’s demise, angering Francis. The Medina family physician, Dr. Leon (Antony Carbone), finally tells Francis that his sister died of fright after becoming morbidly obsessed with the torture chamber, then growing mentally unbalanced, and ultimately falling victim to heart failure.

Vincent Price and Barbara Steele

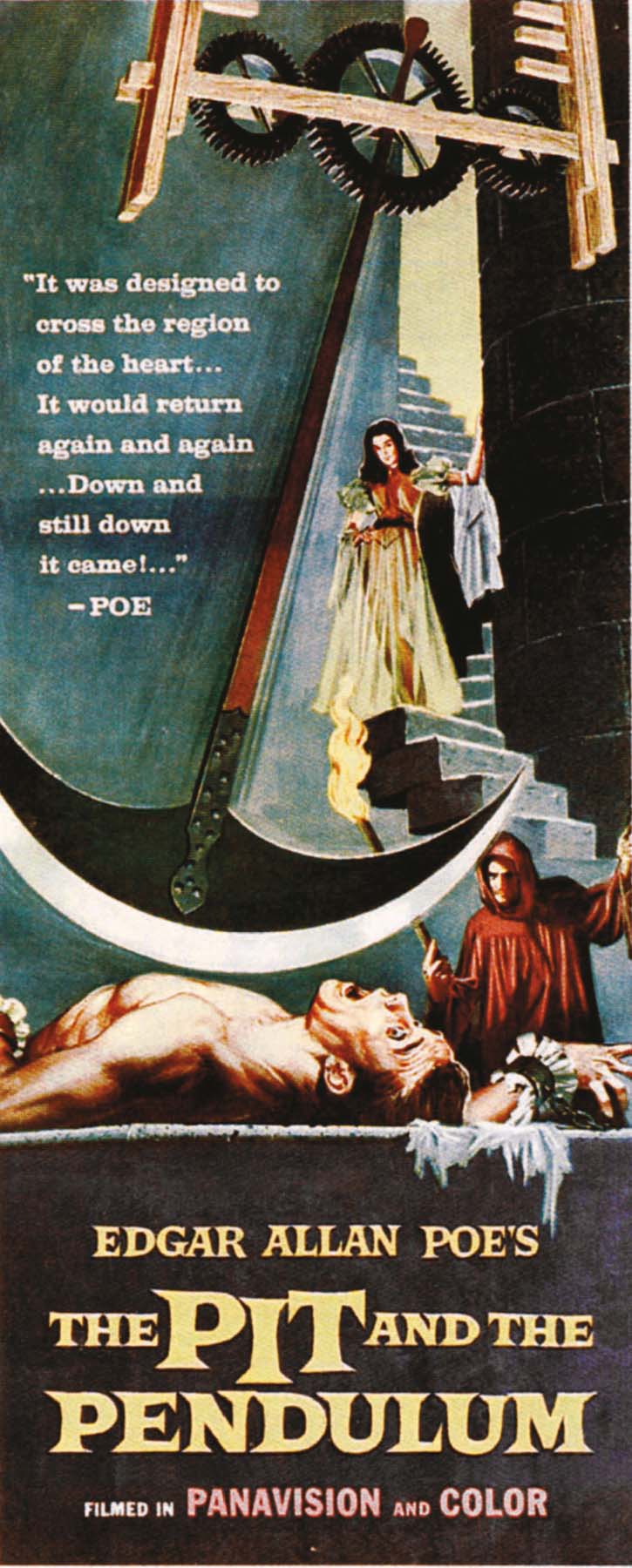

Insert card for The Pit and the Pendulum

Francis remains skeptical, and Nicholas’s sister, Catherine (Luana Anders), tells him about Nicholas’s traumatic childhood, and how he watched his father murder his unfaithful wife, Isabella, by entombing her behind a brick wall while she was still living. Nicholas is fixated on the idea that Elizabeth also may have been interred alive and is now haunting him. He insists that her tomb be opened. The withered, painfully contorted corpse clearly indicates that she was indeed the victim of premature burial and died trying to claw her way out.

The fear of being buried alive was a real, if largely unjustified, anxiety in the early nineteenth century, when Poe was drawn to the theme. Well-to-do families were known to equip their burial sites with elaborate emergency systems and escape hatches. Since the odds of being interred prematurely were vanishingly small, it seems clear that people who fell victim to the obsession were baroquely bargaining with the idea of death itself. Poe’s stories “The Premature Burial” and “The Fall of the House of Usher” feature characters who worry about being buried alive or actually suffer the fate, like Roderick Usher’s unfortunate sister Madeline. An obsession with dying and dead women informs Poe’s imagination generally, as it does Matheson’s script for The Pit and the Pendulum.

John Kerr and Vincent Price, getting into the swing of things

Vincent Price, John Kerr, and Luana Anders

Matheson reveals Elizabeth not to be dead at all, but plotting with her lover, Dr. Leon, to drive Nicholas mad and gain control of his estate. They succeed in pushing him over the edge, but controlling any aspect of him is another matter entirely. In his mind he becomes his own sadistic father, eager to resurrect the ne plus ultra of diabolical torture: slow death beneath a huge, swinging pendulum blade, lowered degree by degree via merciless clockwork.

Like House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum benefits from sumptuous art direction, making use of antique-filled rooms decorated with paintings and murals rendered in the distinctly midcentury-modern style of the 1960s—an unconventionally theatrical conceit that adds considerably to the dreamlike atmosphere. The neo-impressionistic, hooded Inquisition figures painted on the torture chamber’s walls effectively blur distinctions between the familiar present and an unfamiliar and very dangerous past.

Victoria Price recalled Roger Corman as “an expert at creating masterful films on limited budgets and very short shooting schedules,” but “somewhat less adept at directing his actors, and Vincent’s performance in The Pit and the Pendulum was regarded as being somewhat more over the top than his restrained turn in House of Usher.” The Hollywood Reporter called Price’s acting “characteristically rococo” in the film, and it was true that his screen persona was steadily drifting toward the unabashed hamminess his fans adored and that eventually became his career trademark.