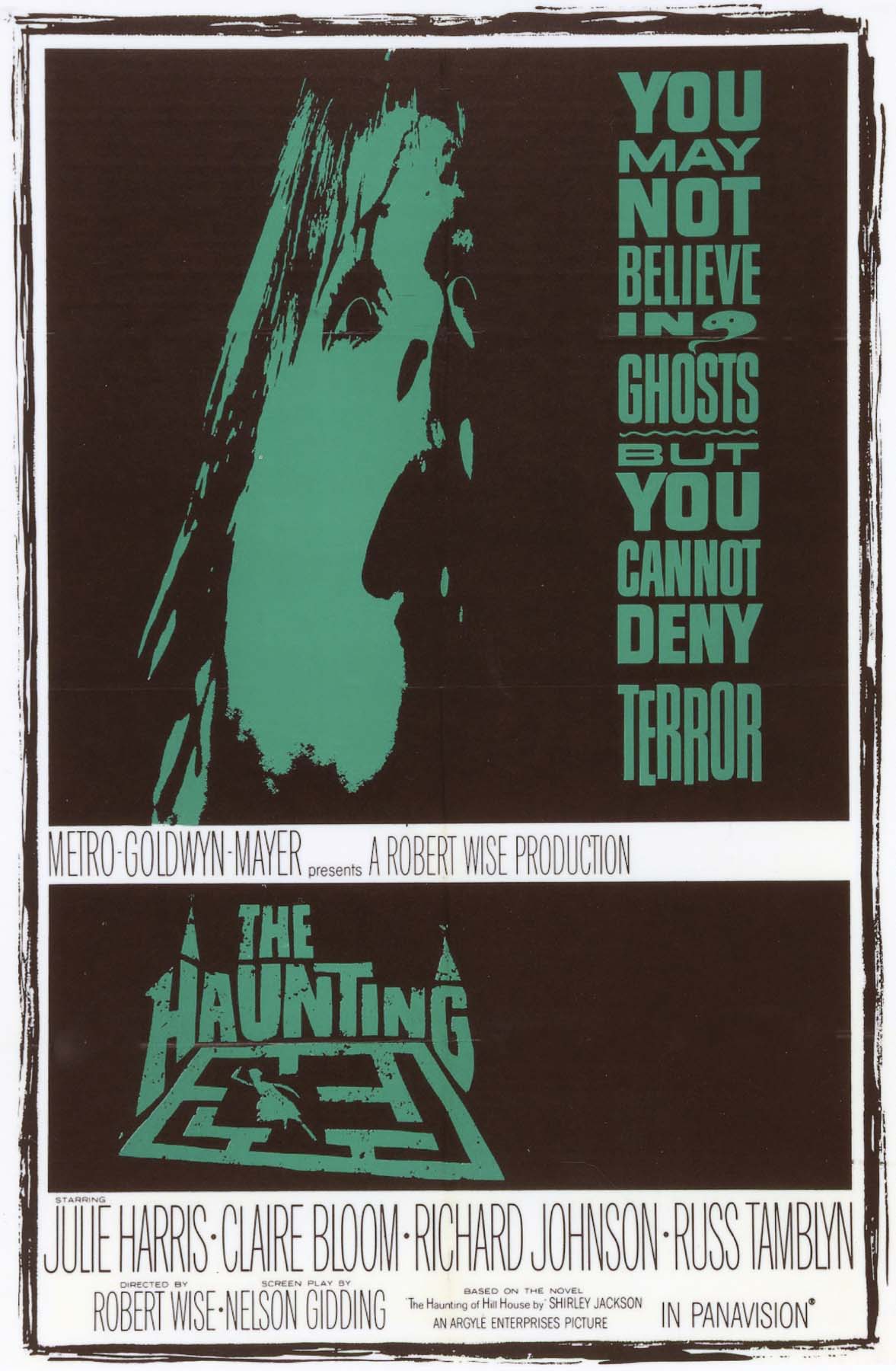

CAN A HOUSE BE EVIL FROM THE BEGINNING? CAN A HOUSE BE BORN BAD?

Dr. John Markway, a New England paranormal investigator, leases the forbidding edifice known as Hill House, a purportedly haunted mansion constructed in Massachusetts in the late nineteenth century, and cursed by tragedy from the beginning. The original owner built it for his wife, but she died in a carriage accident while arriving at the house for her first visit. The owner’s second wife was killed falling down the stairs, and his daughter became a lifelong recluse whose caretaker/nurse inherited the property, only to hang herself from a towering spiral staircase in the library. Hill House has now stood empty for many years.

In addition to the owner’s son, Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn), present as a condition of the lease, and not for any interest in the supernatural, Markway is joined by an experienced psychic, Theodora (Claire Bloom), also called Theo; and by Eleanor Lance (Julie Harris), a meek, quirky, and possibly unstable woman who nonetheless is on record for having experienced credible poltergeist phenomena as a child. Eleanor, we learn, always sleeps on her left side because “I read somewhere that it wears your heart out quicker.” She is currently wrestling with guilt over the death of her invalid mother, to whose care her adult life has been largely dedicated. Now she lives as a barely tolerated spinster with her sister and brother-in-law, sleeping on their sofa. They blame her for her mother’s death.

Claire Bloom, Russ Tamblyn, Julie Harris, and Richard Johnson

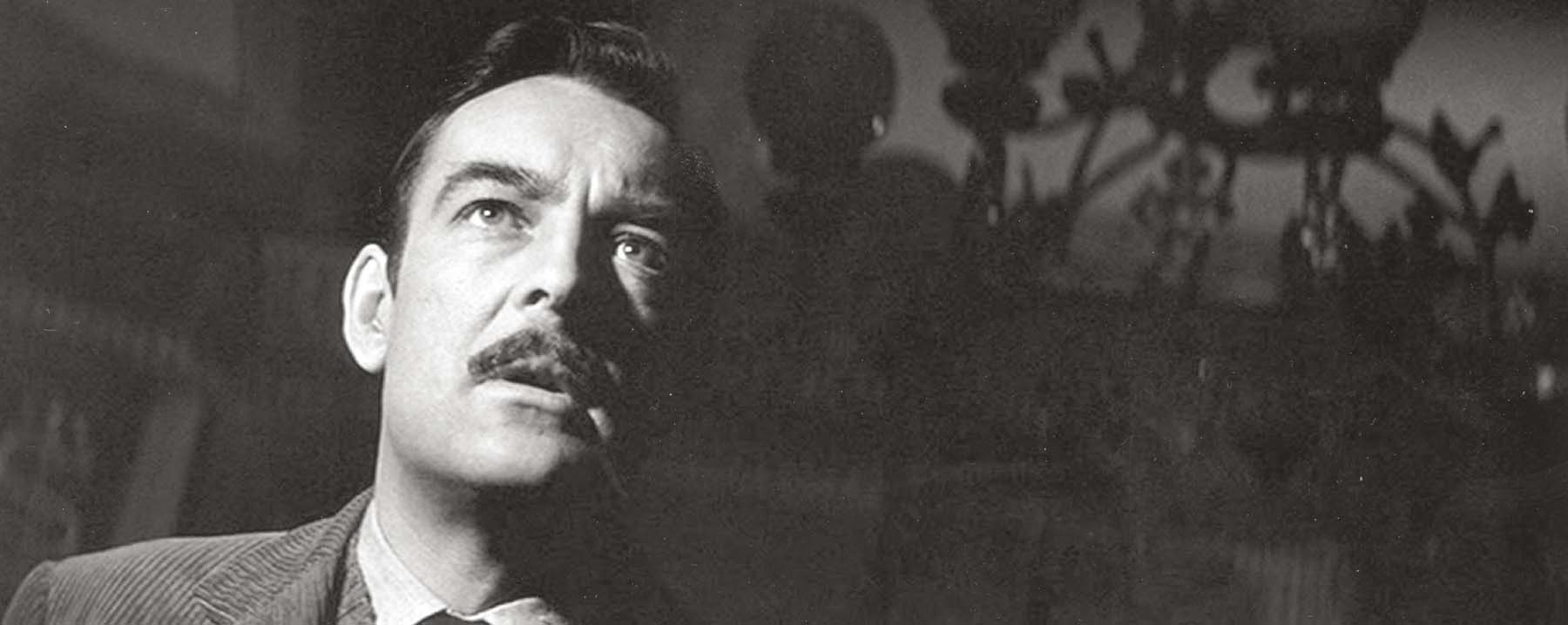

Richard Johnson

Lois Maxwell

Russ Tamblyn

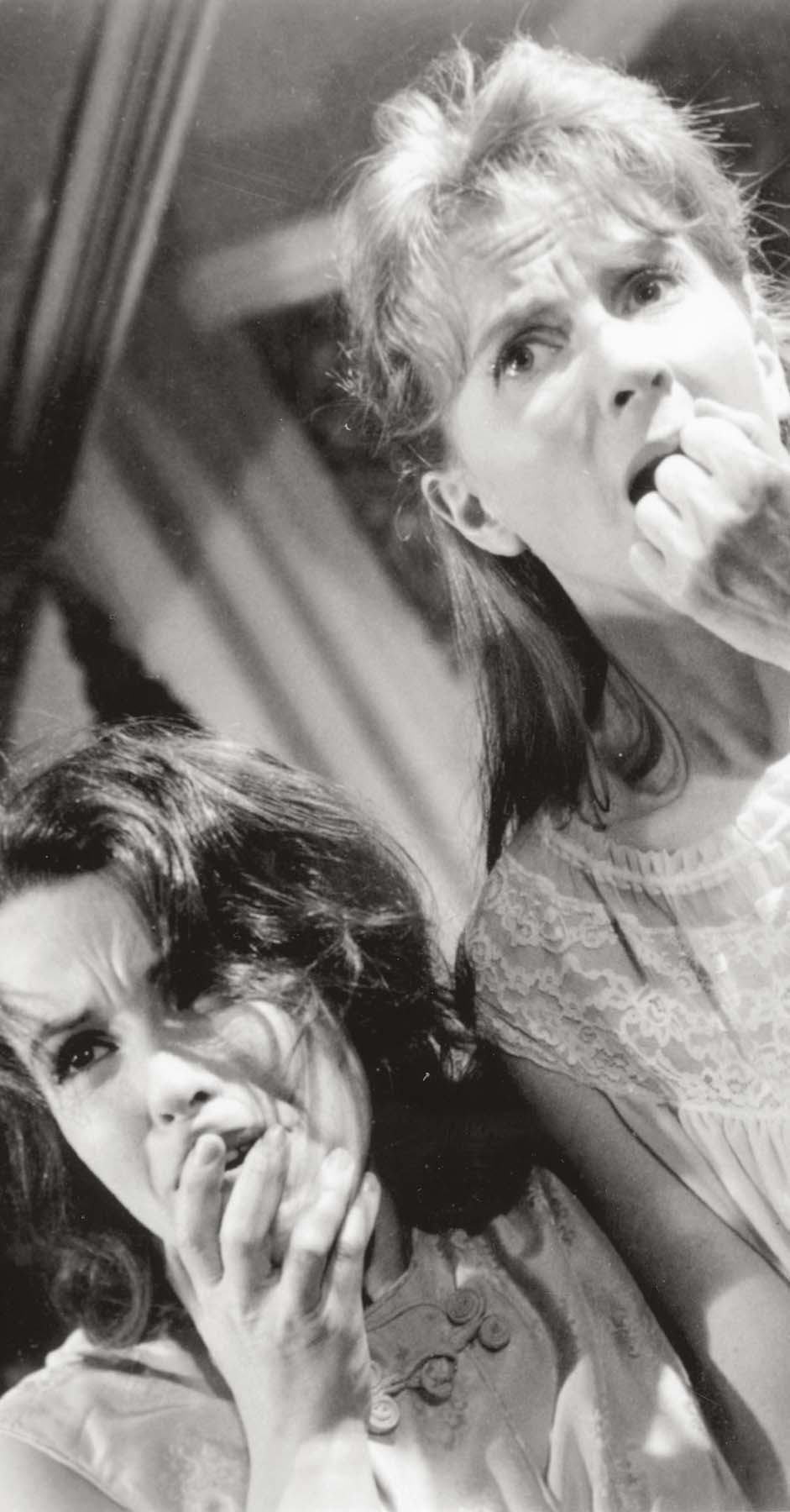

On the very first night at Hill House, the women are terrified by sounds outside Theo’s room—a thunderous banging and the reverberating laughter of a young girl. The next day, the team locates a mysterious cold spot outside the nursery, and another night of unexplained noises follows. Most disturbing to Eleanor is a menacing graffito scrawled across a wall: “HELP ELEANOR COME HOME.” Theo moves into Eleanor’s room, where they share the same bed. In the middle of the night, voices are heard again: the muffled, indistinct sound of a man, the laughter of a woman, and the crying of a young girl. Eleanor asks Theo to hold her hand and feels a powerful grip in return. Eleanor shouts at whatever entity is causing the girl such terrible pain to stop. When Theo turns on the light, we see that Eleanor has been sleeping on a couch across the room from Theo. Eleanor stares at her hand in terror. Whose hand has she been holding?

When Robert Wise agreed to direct The Haunting, he wondered if the story might be told as an expression of Eleanor’s deteriorating mental state rather than as a supernatural occurrence. He consulted with novelist Shirley Jackson herself, who told him she intended the events in the book to be entirely supernatural, but she made no objection to Wise’s idea. The finished film seems to be a deft compromise. Could it be that malignant spirits and mental illness coexist, and that some entity is feeding on—and simultaneously fueling—Eleanor’s psychological problems?

However you decide to interpret the tale, The Haunting is without question one of the finest ghost stories ever filmed. Wise once said he intended the picture to be something of an homage to Val Lewton, for whom he directed The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1945). Both films allowed audiences to complete in their own imaginations frightening things hidden in shadows. The Haunting does Lewton one better with truly extraordinary black-and-white cinematography by Davis Boulton, who uses a camera that moves, prowls, and swoops in ways you might reasonably expect from a ghost.

The female leads give exceptionally nuanced, meticulously detailed performances. Harris’s Eleanor, a totally convincing characterization of a child-woman adrift, immediately conjures her famous and poignantly similar role as Frankie in A Member of the Wedding (1952). Claire Bloom’s Theo actually has, or convincingly fakes, an ability to read minds, and she finds a number of mischievous things to do with the power (yes, exactly what all of us would do). The treatment of the character’s lesbianism is surprisingly straightforward for a 1963 movie. Bloom’s aggressively chic wardrobe was specially created by Mary Quant, an iconic designer of the 1960s.

Wise is most remembered for big, mainstream films like The Sound of Music and West Side Story, but The Haunting shows him to be as inventive, risk-taking, and forward-looking as a young Orson Welles, for whom he had edited Citizen Kane twenty-two years earlier. The Haunting contains many visual echoes of Kane, especially in the moody Xanadu prologue.

Claire Bloom and Julie Harris

If you enjoyed The Haunting (1963), you might also like:

THE UNINVITED

PARAMOUNT PICTURES, 1944