THE HUNGRY DEAD RETURN AND THE MODERN ZOMBIE MOVIE IS BORN.

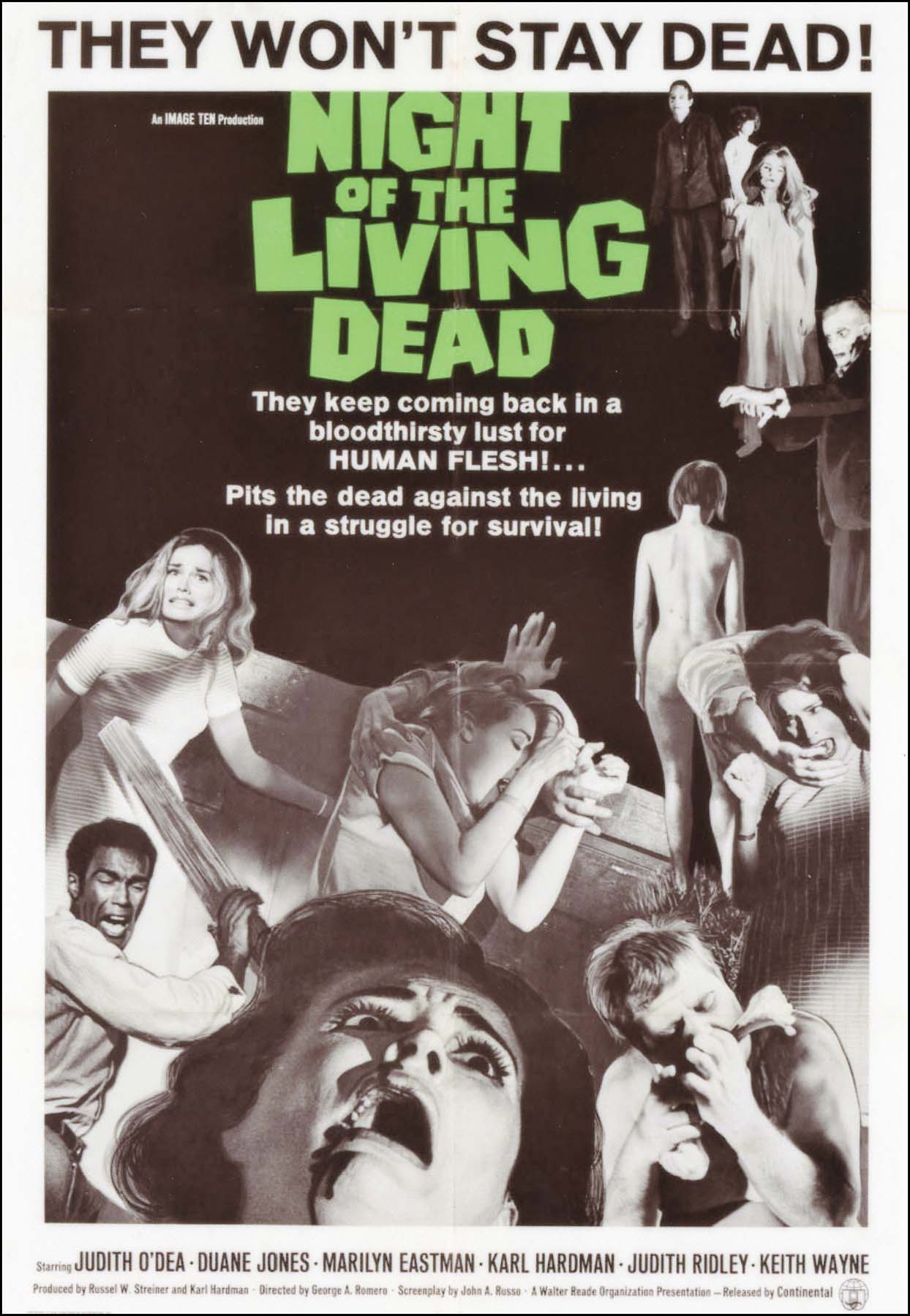

George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead is the most famous and influential zombie movie, even though the word “zombie” isn’t uttered even once in the course of the film. One of the most legendary independent films ever made, it was shot on a shoestring around Pittsburgh, using as its primary set a house already scheduled to be torn down. The living dead would get the first crack at real demolition.

One cloudy Pennsylvania afternoon, sister and brother Barbra and Johnny (Judith O’Dea and Russell Streiner) visit their father’s grave in a rural cemetery. A strange, lurching man appears, unnerving Barbra but prompting Johnny to mockingly imitate Boris Karloff, intoning “They’re coming to get you, Barbra.…” The man becomes violent, striking Johnny’s head on a grave marker and instantly killing him. The nightmarish figure chases Barbra to her car and tries to break in. Hysterical, Barbra wrecks the car and flees on foot, eventually coming to a farmhouse, where she discovers a woman’s rotting corpse at the top of a staircase. Strange, menacing figures, including the cemetery walker, begin to surround the house. A man named Ben (Duane Jones) appears, behaving normally and rationally. He prevents Barbra from fleeing and barricades the doors and windows.

Barbra exhibits all the symptoms of profound mental shock. Ben finds a radio and a rifle, then discovers a family, Harry and Helen Cooper (Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman) and their injured daughter, Karen (Kyra Schon), hiding in the cellar. A teenage couple, Tom (Keith Wayne) and Judy (Judith Ridley), have also taken refuge after hearing radio reports of mass murder.

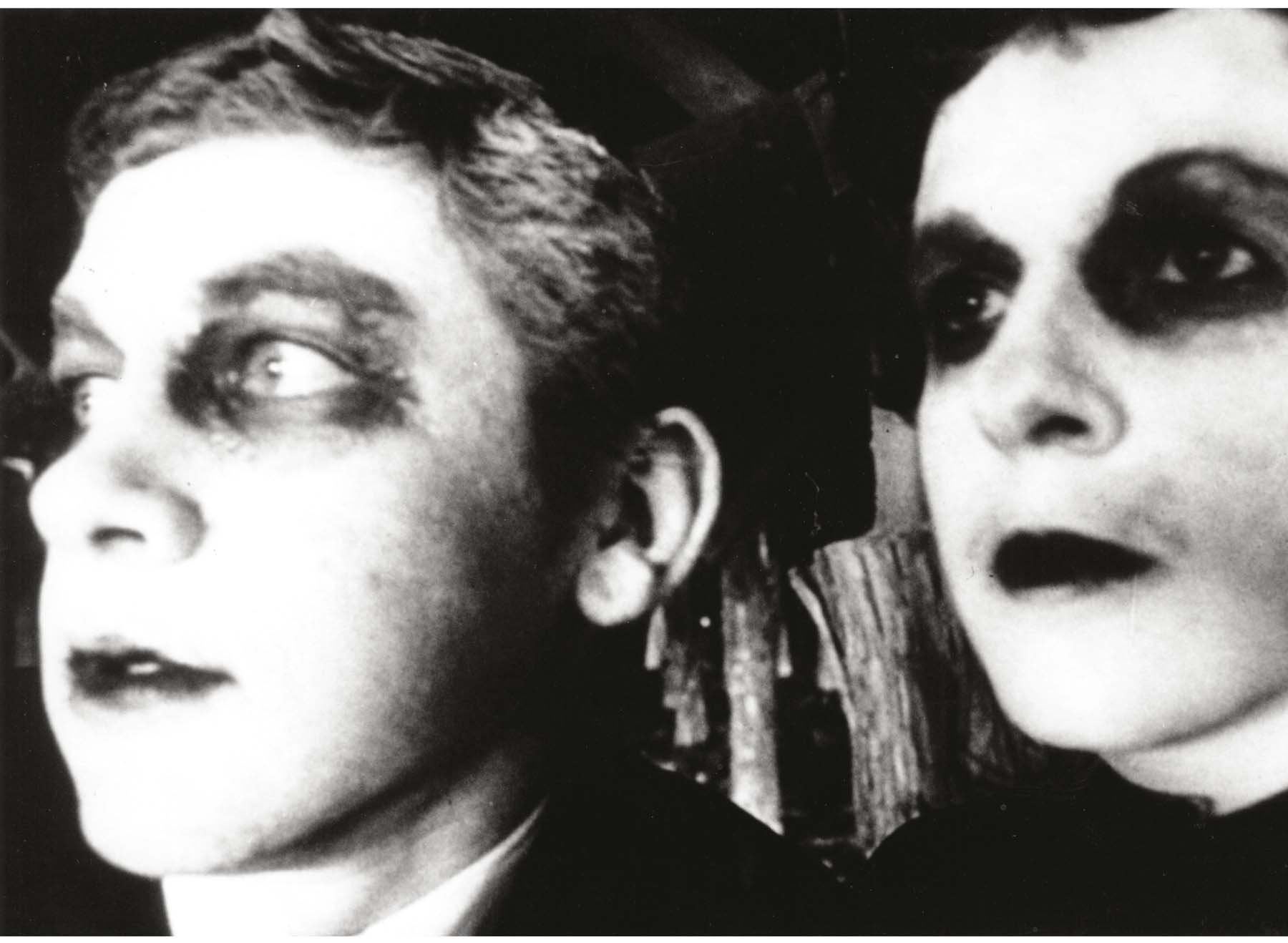

Romero’s zombies, played by nonactors, were unnervingly normal looking.

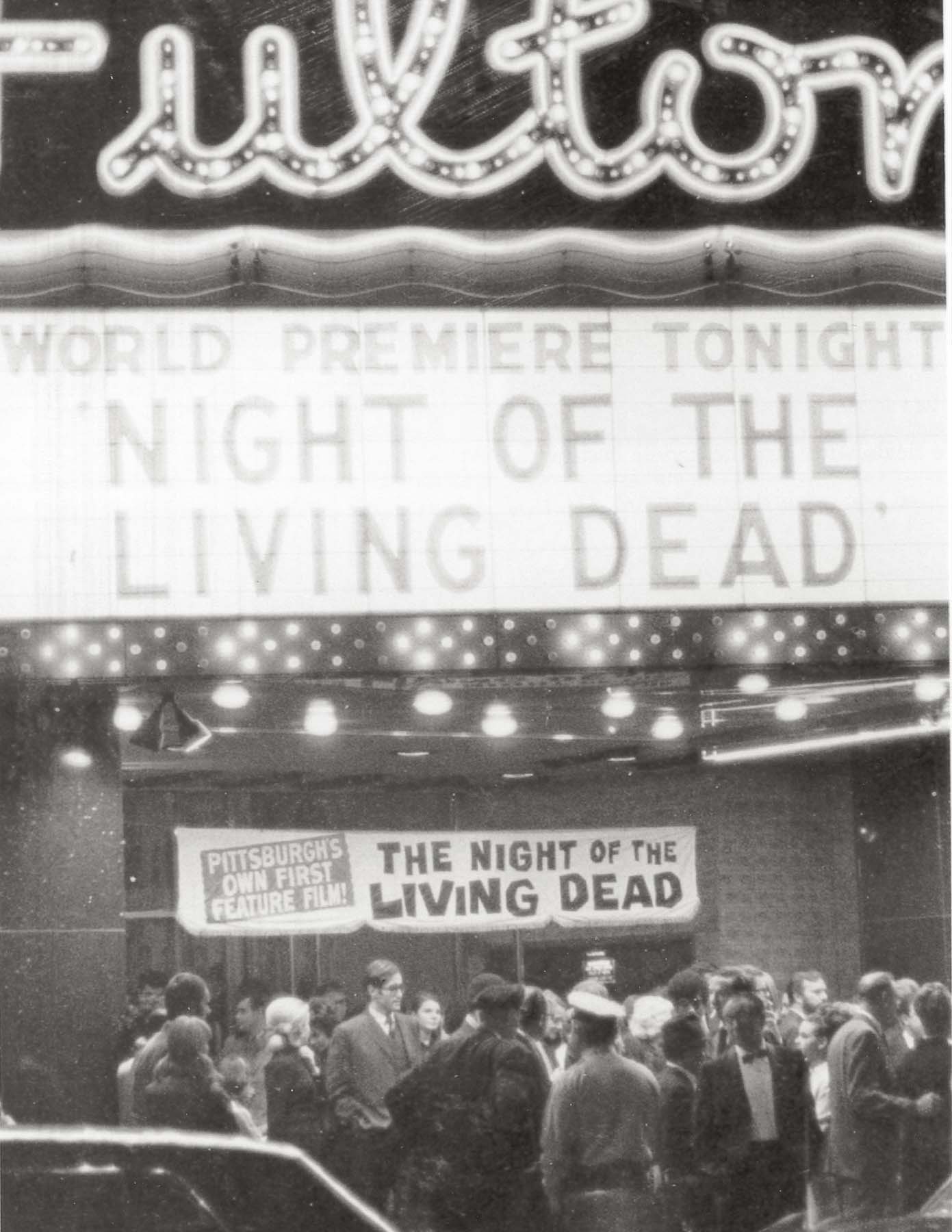

The Pittsburgh world premiere of Night of the Living Dead.

As more barricades are erected throughout the house, a broadcast report finally offers an explanation for all the bizarre violence. The recently dead have returned to life and are eating the flesh of the living. There is speculation that radioactive fallout from a returning space probe may be to blame, but nothing is known with certainty. The “ghouls” can be killed by a bullet to the head or by being burned. Karen needs immediate medical care, and a plan is made for Tom and Judy to drive her to an emergency facility announced on the radio. While they attempt to refuel at the farm’s gas pump, Ben and Harry keep the walking dead at bay with Molotov cocktails, but a mishap occurs and the vehicle’s fuel tank explodes, killing the teens and attracting the animated corpses, who make a grisly feast of the freshly charred meat.

It’s no spoiler to say this is a film that ends badly for every character. Since Ben was played by a black actor, his downbeat fate in the last scene drew outraged comment in 1968, a critical year in the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr., after all, had been killed just six months before the film was released, and the mood of the country was still very raw. A daily backdrop of senseless death was provided by the Vietnam War, a never-ending conflict that, for millions of people, was as incomprehensible as a zombie apocalypse. Protests and riots, like the one that occurred at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that year, gave further credence to the idea that the social structure might be breaking down. The real world may not have been far removed from George Romero’s horror fantasy after all. As Village Voice film critic J. Hoberman noted, the film “was made in the most violent year in American history since the Civil War. It’s shot like cinema vérité, as though it were the evening news. It never wavered from its desire to terrorize the audience and offer no hope at the end.”

Romero intended no social commentary at all; he had, for instance, cast Duane Jones for his acting talent and not to send any message about race. But because the sociopolitical climate of 1968 was so unstable, many audiences regarded simply viewing the film as a kind of protest, a transgressive gesture against the stubborn status quo represented by the parents, film critics, and even editorial writers who railed against the film. Variety’s reviewer wrote that “the film casts serious aspersions on the integrity of its makers, distrib[utor] Walter Reade, the film industry as a whole, and exhibitors who book the pic, as well as raising doubts about the future of the regional theatre movement and the moral health of filmgoers who cheerfully opt for unrelieved sadism.” The movie would have the last laugh, however. Far from establishing a new low in cinema, as was charged, it instead became one of the most imitated films in movie history, partially because it entered the public domain when the Walter Reade Organization failed to properly register its copyright. Night of the Living Dead was chosen for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art and added by the Library of Congress to its National Film Registry for motion pictures deemed “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

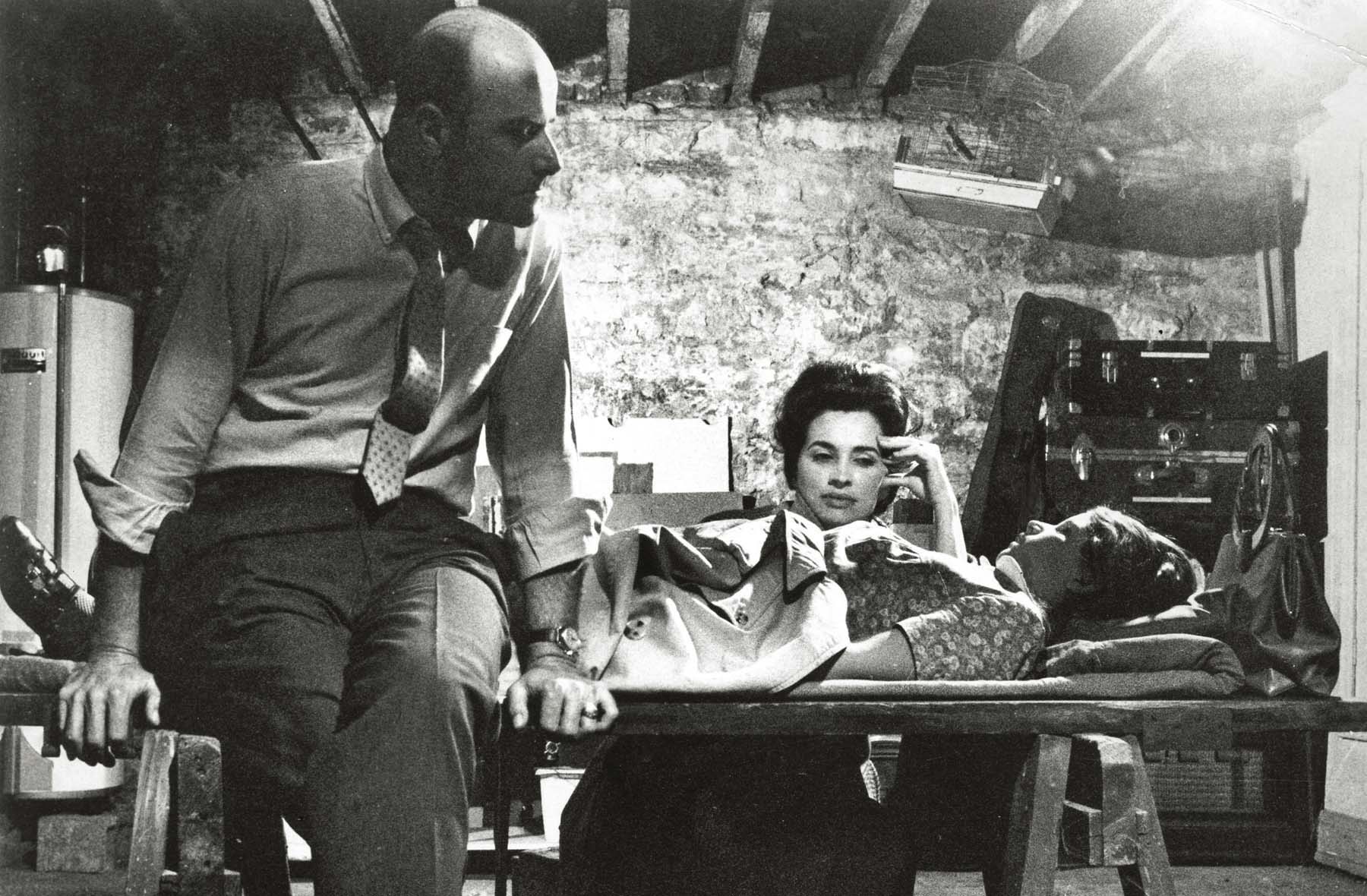

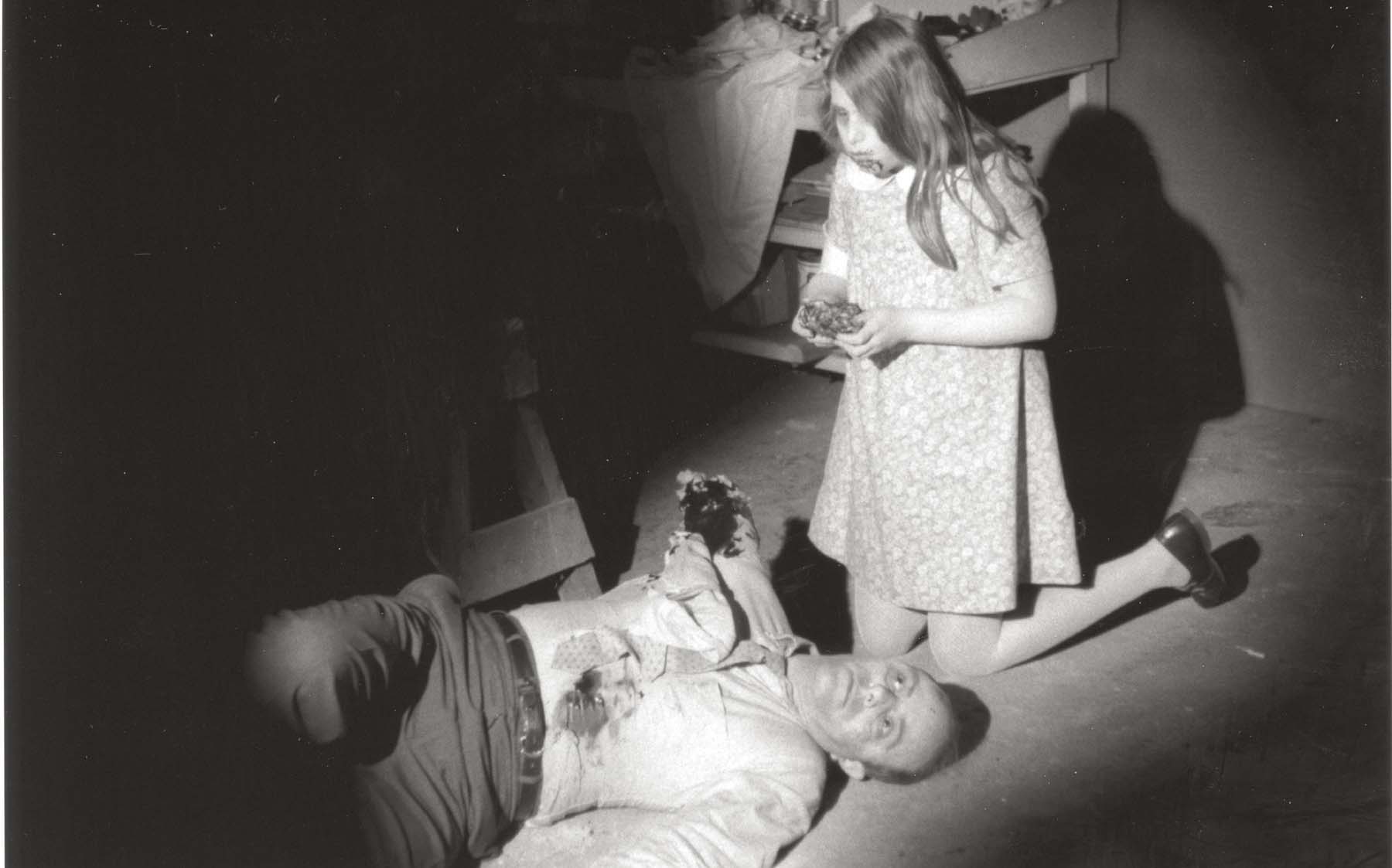

Harry and Helen Cooper (Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman) and their injured daughter Karen (Kyra Schon) hole up in the farmhouse basement.

“They’re coming to get you, Barbra.…” Russell Streiner and Judith O’Dea have their first experience with the walking dead in a cemetery.

Romero went on to trailblaze the zombie genre with increasingly gruesome and sharply satirical films like Dawn of the Dead (1978), which introduced the shopping mall zombie, and the ultra gorefest Day of the Dead (1985). He died in 2017, after having an almost incalculable impact on fantastic filmmaking around the world. If imitation is indeed the sincerest form of flattery, then George Romero must be one of the most lionized directors in the history of cinema.

Duane Jones and Judith O’Dea

The clawing, hungry dead batter every barricade.

Karen turns carnivorous, killing and eating her father.

If you enjoyed Night of the Living Dead (1968), you might also like:

CARNIVAL OF SOULS

HERTS-LION INTERNATIONAL, 1962