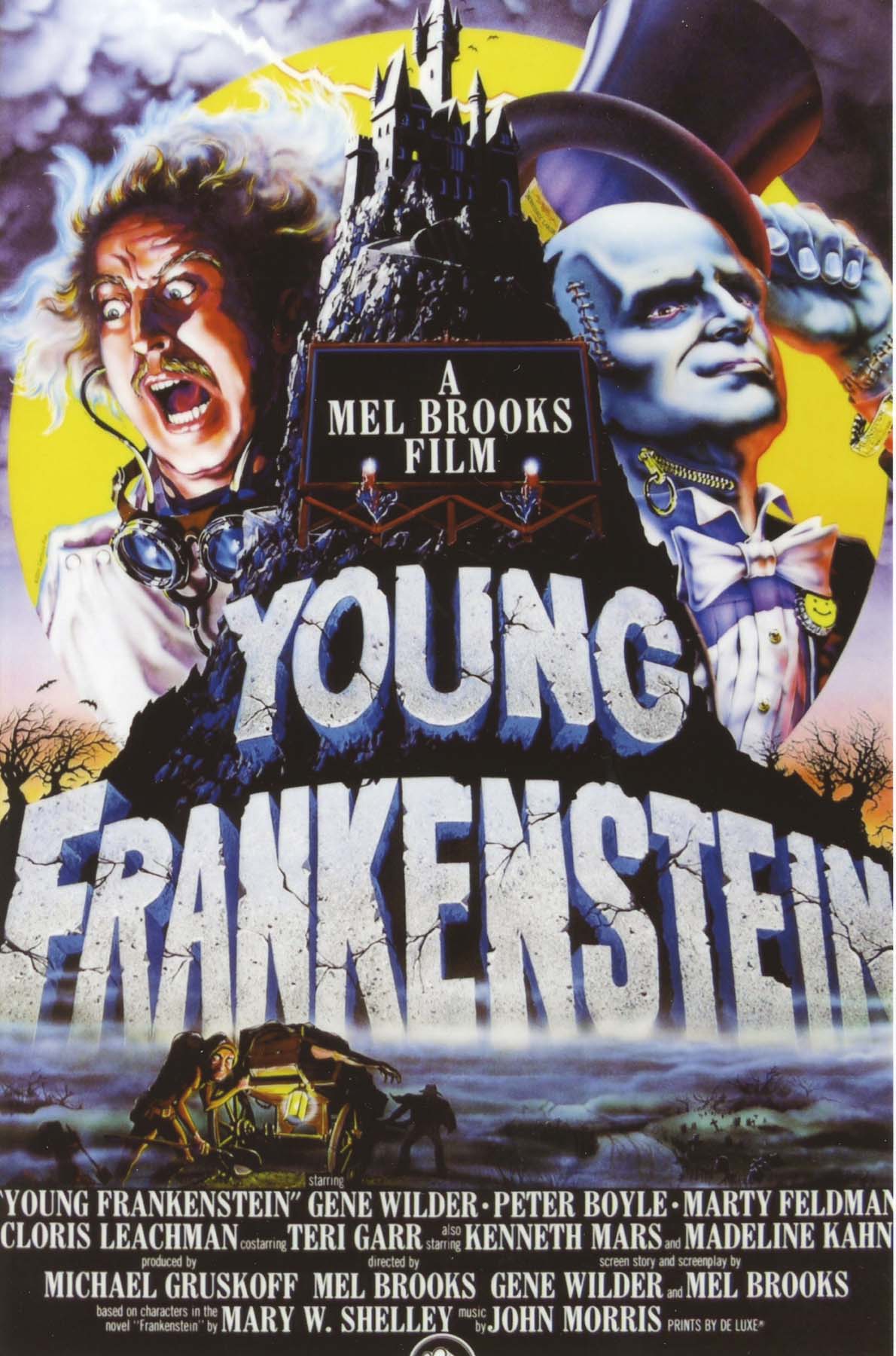

THE WORLD’S MOST LEGENDARY MONSTER, BUT NOT THE SAME OLD SONG AND DANCE.

Although both films are recognized as comedy classics, Mel Brooks’s Young Frankenstein did more for horror movies than Blazing Saddles did for Westerns. Blazing Saddles is an inspired but eclectic assemblage and send-up of genre conventions, but Young Frankenstein is more carefully constructed around a single, time-honored storyline.

Dr. Frederick Frankenstein (Gene Wilder), who teaches at an American medical college, resents any reference to or publicity about his notorious grandfather, Victor Frankenstein, the man who made a monster, and who really paid for it. In order to put further distance between himself and his forebear, Frederick pronounces the family name “Fronkenschteen,” though few people honor his preference (everyone, after all, knows who, or what, Frankenstein is). When Frederick’s great-grandfather dies in Transylvania, he learns that he has inherited his family’s castle, and he immediately sets out to see the estate.

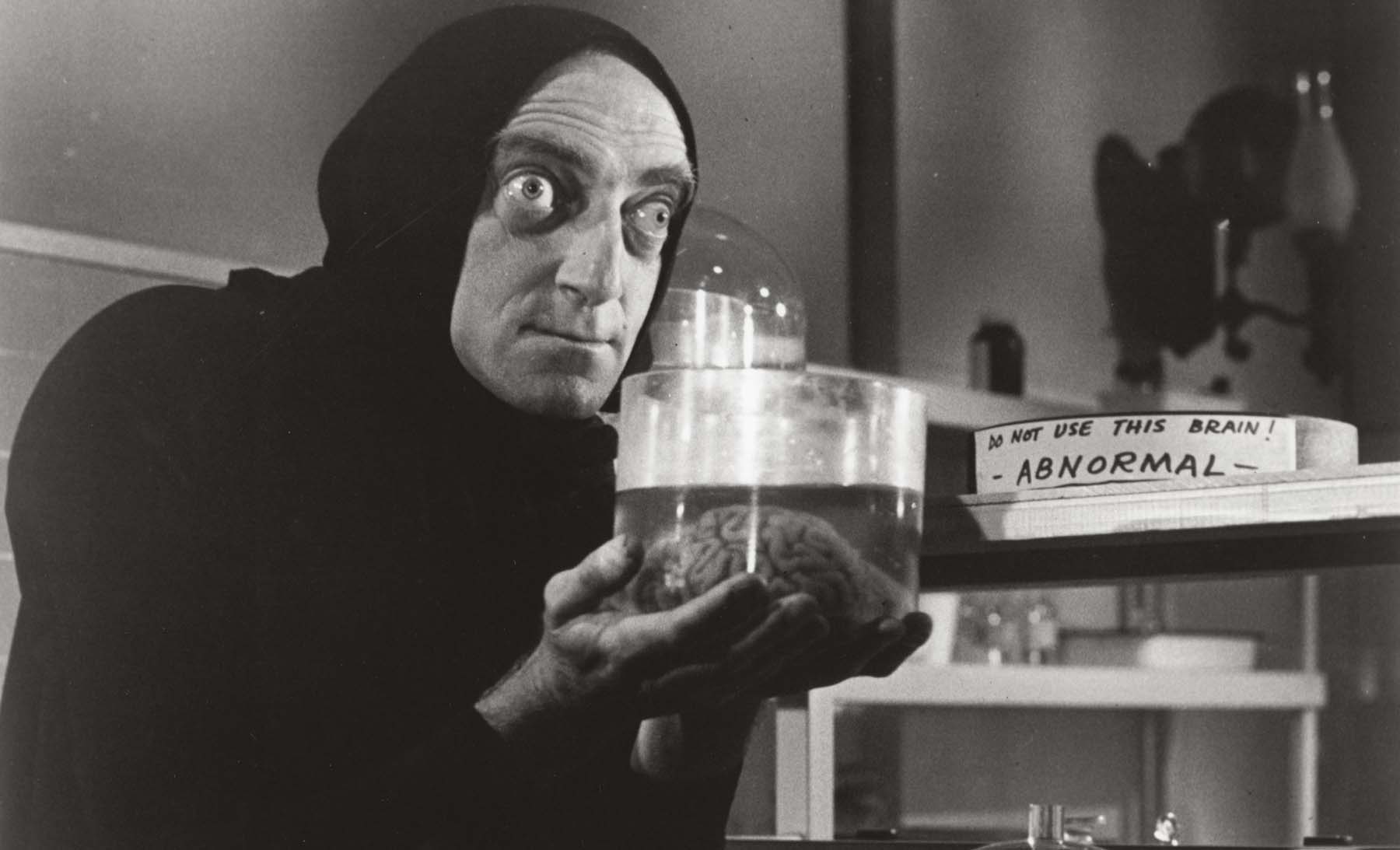

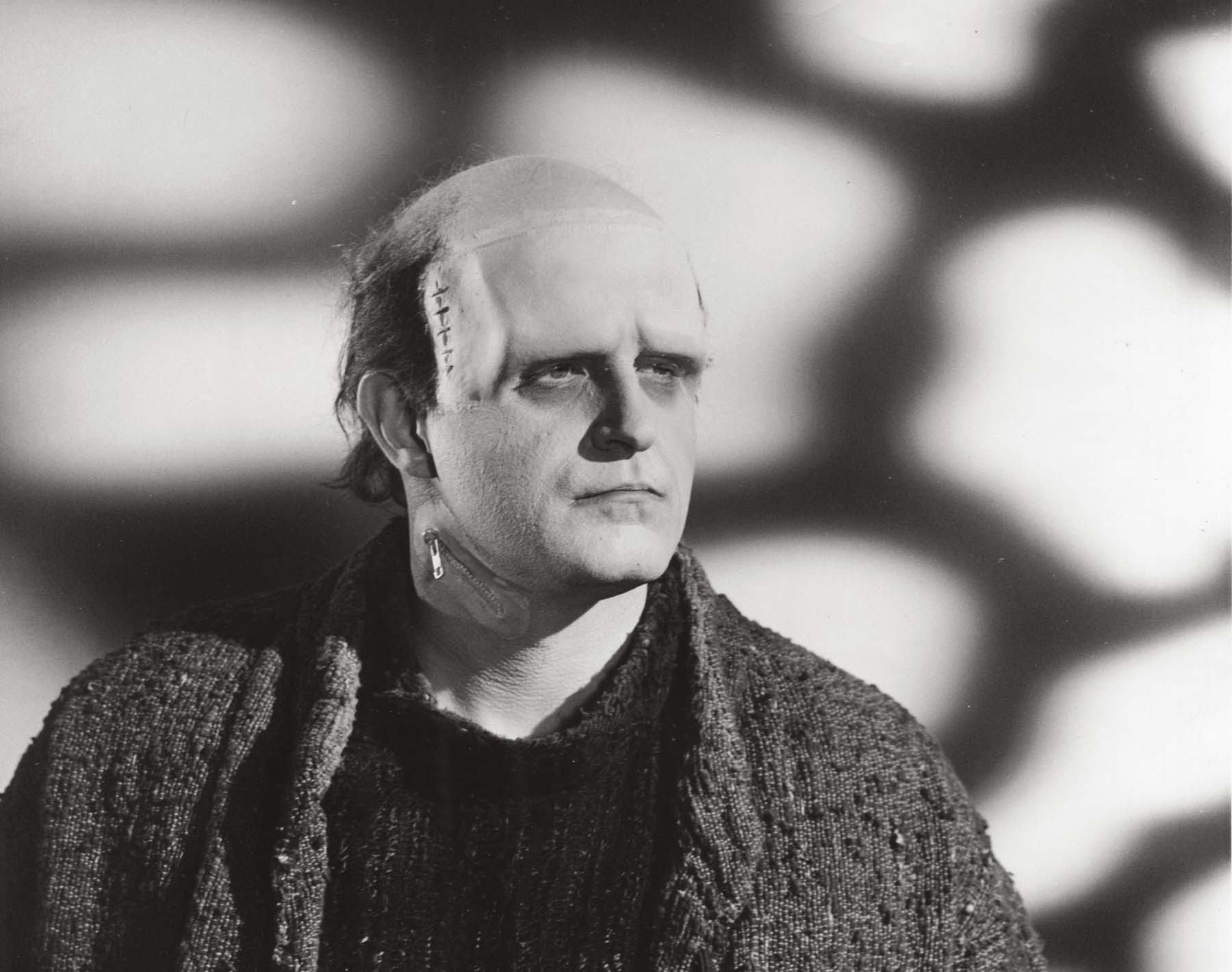

Arriving at the Transylvania train station, Frederick meets a hunchbacked, pop-eyed servant from the castle named Igor (Marty Feldman), who pronounces his name “Eye-gore.” The estate is looked after by a formidable housekeeper, Frau Blücher (Cloris Leachman), the very utterance of whose name sends horses rearing and whinnying in terror. Frederick discovers his grandfather’s secret laboratory and personal journal—self-effacingly titled “How I Did It”—which reveals the ultimate secrets of life. Thunderstruck, Frederick decides he must continue the experiments, and soon, with the help of Igor and a curvaceous laboratory assistant named Inga (Teri Garr), he is piecing together parts of corpses he intends to reanimate with the brain of a brilliant, recently deceased professor. Igor, however, botches the brain theft and substitutes another cerebral specimen clearly labeled “ABNORMAL.” The result is a confused but nonetheless endearing monster (Peter Boyle). Boyle’s makeup manages to strongly evoke the indelible look of Boris Karloff without really copying it. Among the differences is a zipper on the neck, an interesting (and very funny) update on the sutures and clamps usually employed to keep the head in place.

Frederick Frankenstein (Gene Wilder) exults in his recently acquired mastery of the secrets of life.

Left to right: Mel Brooks, Peter Boyle, Marty Feldman, Gene Wilder, and Teri Garr

Marty Feldman as Igor, who can be a tad butterfingered around brain jars

Frederick’s betrothed, Elizabeth (Madeline Kahn), arrives, putting a bit of a strain on Frederick’s ongoing affair with Inga, though not too much, since Elizabeth is a glamorous but fairly refrigerated fiancée. She does eventually warm up to the monster—letting down her hair and electrifying it with permanent-wave lightning bolts—amid multiple, hammered-home references to the creature’s enviously enormous endowment.

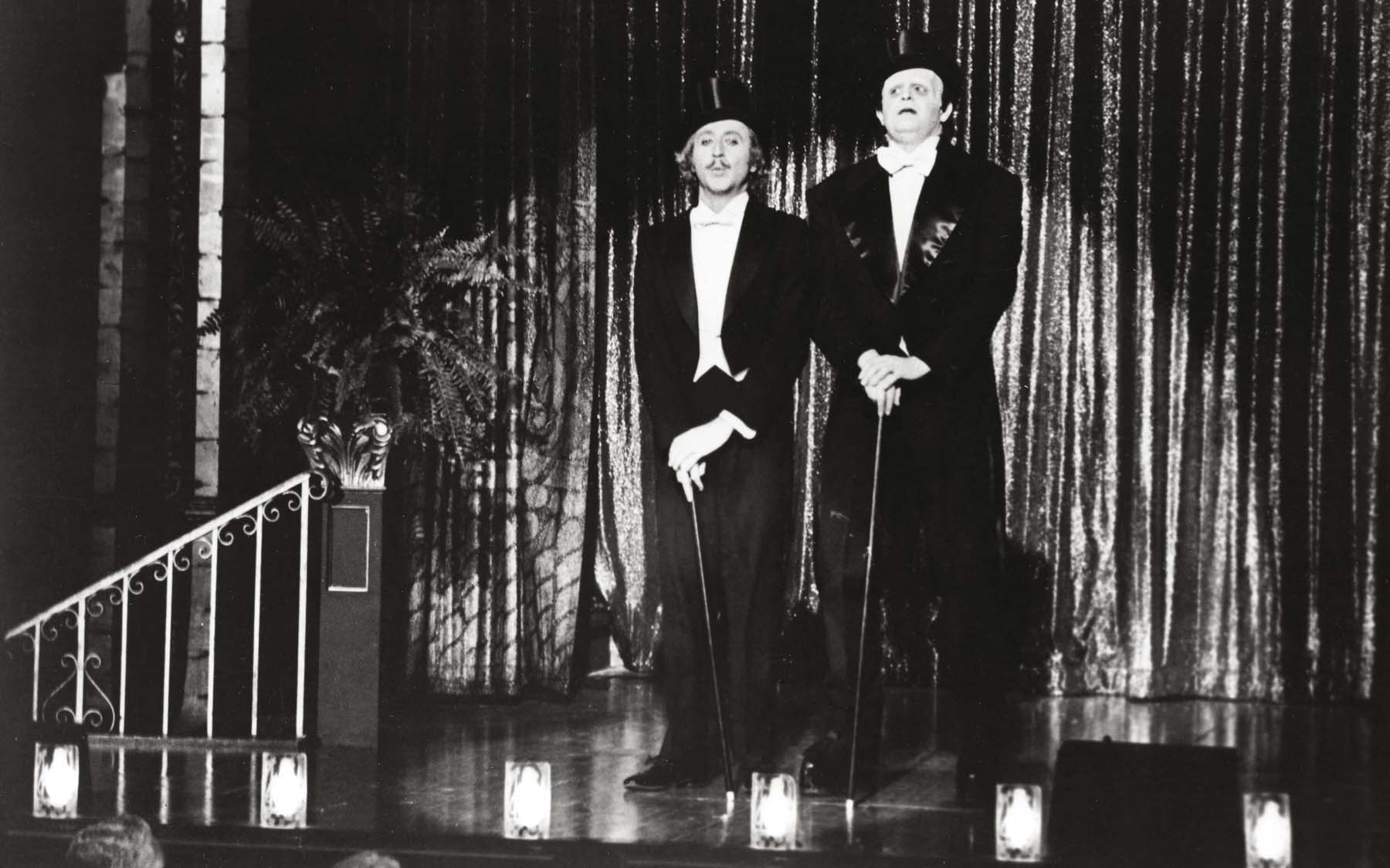

Simultaneously a loving homage and an irreverent spoof, Young Frankenstein follows the sturdy template of the Universal films that starred Boris Karloff (Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and Son of Frankenstein). Wilder and Brooks’s script revisits and hilariously upends one classic scene after another, including the “It’s alive!” creation sequence, the monster’s encounters with a blind hermit (Gene Hackman), and its meeting with a little girl, which ends on a note of slapstick instead of tragedy. Some of the gags are enjoyable groaners exhumed from the catacombs of vaudeville; others are off-color winks to a modern audience; and some—like the top-hat-and-tails rendition of “Puttin’ on the Ritz” performed by Wilder and Boyle for a medical conference—are hilariously original and, once seen, unforgettable. The film has consistently and understandably been included on numerous lists of the best motion picture comedies ever made. Produced on a budget of $2.78 million, it grossed $86.2 million in first-release rentals.

20th Century Fox pressed Brooks to shoot the film in color, but he wisely resisted. The evocative, velvety black-and-white art direction and cinematography by Dale Hennesy and Gerald Hirschfeld result in one of the most meticulously re-created visions of a bygone Hollywood style ever attempted, if not the most successfully realized. A cartoonier visual approach might well have been adopted, but it’s doubtful it would have pressed the nostalgia buttons as effectively. The air of hyperrealistic fun and fantasy is further enhanced by the presence of some of Kenneth Strickfaden’s original, crackling electrical equipment used at Universal in the 1930s, which was still available and operating in 1974.

Brooks retooled the film as a popular Broadway musical in 2007. While it didn’t achieve the success of Brooks’s previous movie-into-musical hit, The Producers, Young Frankenstein ran for two years in New York, had two successful American tours, and was revised and revived in 2017 for a well-received eleven-month run in London.

Peter Boyle as the monster

The film’s pièce de résistance, “Puttin’ on the Ritz”

Cloris Leachman as the terrifying Frau Blücher

If you enjoyed Young Frankenstein (1974), you might also like:

ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN

UNIVERSAL-INTERNATIONAL, 1948