THE MOVIE THAT MADE OCTOBER 31 GOOSEBUMPY AGAIN.

We don’t know exactly who we are, or where we are, but as seen from the camera’s point of view, we’re somebody prowling around a generic suburban house where a teenaged girl, Judith Myers, is in her bedroom having a tryst with her boyfriend. While the couple finishes their business, we go downstairs to the kitchen, find a drawer, and quietly withdraw a butcher knife. As the boyfriend leaves, our unseen alter ego picks up a plastic Halloween clown mask and puts it on. Our vision is now reduced to what can be observed through a pair of peepholes, but we can see well enough to find our way quickly back to the bedroom, where Judith sits partially nude at a dressing table, combing her hair.

“Michael?” she asks. Her initial annoyance turns to screaming bloody horror as the knife flashes down again and again in front of the eye holes, only partially concealing the killing. The slaughter complete, the mask leads us downstairs and out the front door, where adults are just arriving. This time, when a man’s voice asks “Michael?” and the mask is removed, we move to an objective point of view and realize that we have been seeing the world through the eyes of a six-year-old boy, frozen and vacant-faced in a festive clown costume, still holding the bloodstained knife.

It turns out that the little boy is Michael Myers, a first-grader in Haddonfield, Illinois, who has murdered his older sister for no discernible reason on Halloween night, 1963. He will remain in a semicatatonic state for fifteen years, becoming an enigma and an obsession for his custodial psychiatrist, Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasence). On Halloween 1978, the year he reaches adulthood, Michael escapes while being conveyed to another facility and returns to Haddonfield wearing a cadaverous mask. He begins stalking a chaste and studious babysitter named Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) and savagely kills her more sexually adventurous friends. It’s not long, however, before he zeroes in on Laurie.

The unmasked face of Michael Myers (Will Sandin), a Halloween killer at the age of six

Michael Myers (Tony Moran), all grown up

Beyond its title, Halloween has an especially dynamic relationship with the actual holiday: its launching of the longest-running series of sequels and reboots in Hollywood history coincided with and contributed to the explosive growth of Halloween as the second-biggest retail holiday in America after Christmas. For many years, Halloween held the record as the highest-grossing independent feature ever made. The film made over $70 million on an investment of $300,000, instantly propelling John Carpenter to the front of the line as a bankable purveyor of cinematic fright.

Halloween also helped fuel the ever-expanding urban mythology of Halloween, especially the belief that young people were in mortal peril on October 31 from candy poisoners, kidnappers, and serial killers. In reality, there is no more crime directed at children and young adults on Halloween than on any other day of the year, but the Halloween series continued to draw energy from the cynicism and suspicion taking social root in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, as well as following the Tylenol-tampering deaths and the Atlanta child murders of the early 1980s, both of which were prominently in the news during the weeks running up to Halloween.

The Halloween phenomenon reconnected the holiday to its primary, if forgotten, cultural purpose: a ceremonial acknowledgment of mortality and the never-ending cycles of life, death, and the mysteries that follow. Before John Carpenter reinvigorated the holiday with ritual human sacrifice, did anyone still make a conscious connection between a jack-o’-lantern and a grinning skull? Participants in the harvest celebrations of the ancient Celts understood that life was literally in the balance if the crops failed. But today, even with memento mori overwhelming the mediasphere, most people are still more likely to worry about the availability of pumpkin-spiced lattes than about having enough food for the winter. Modern Halloween is just as much about denying death its power as it is a surrender to it—a grim game of hide-and-seek with a relentlessly determined reaper.

Michael’s alternate Halloween disguise

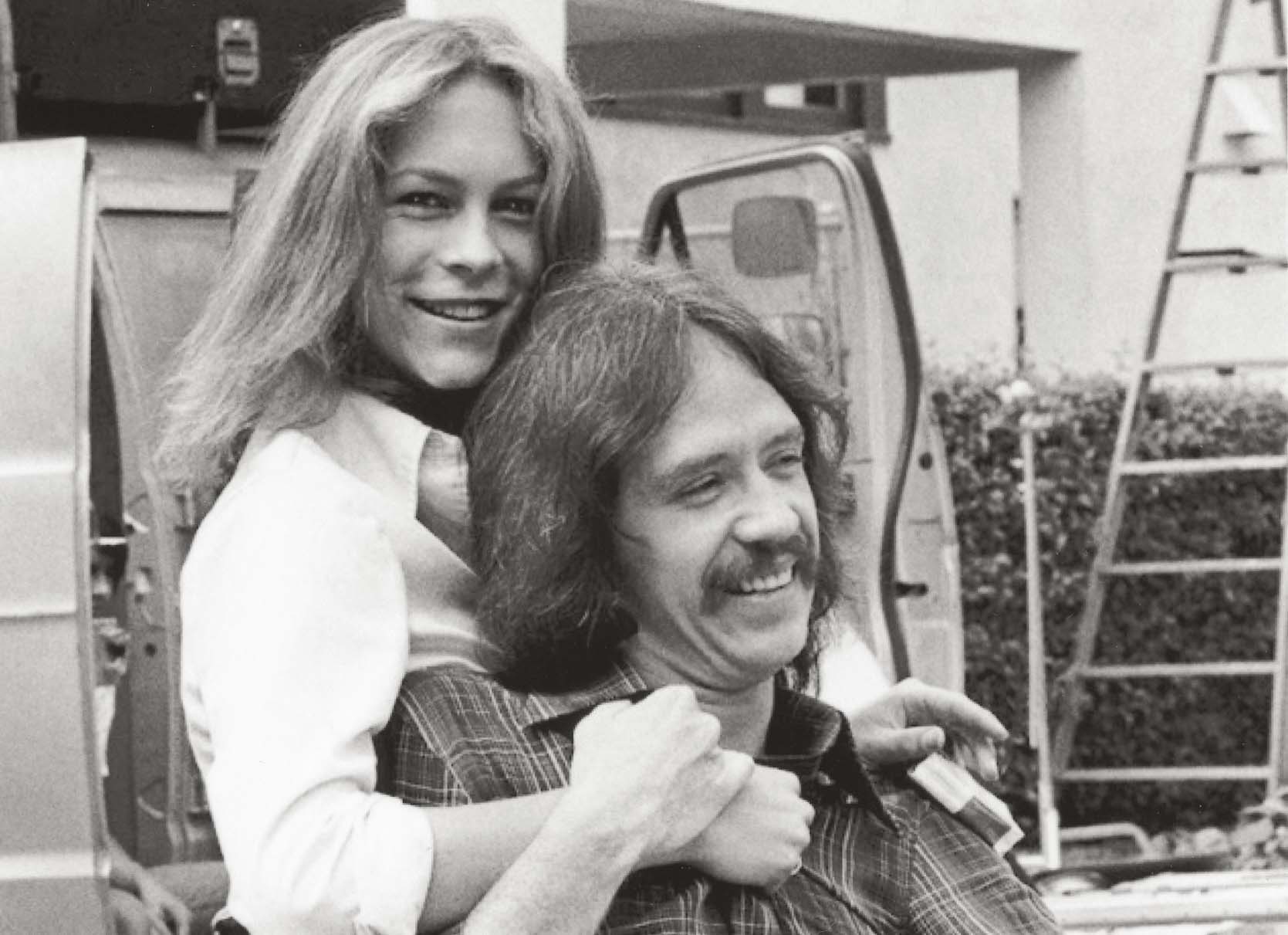

Jamie Lee Curtis and John Carpenter on set

Curtis and Michael in the 2018 reboot

It is often claimed that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was the seminal slasher film, but most recognize Halloween for the distinction. Carpenter’s film is, of course, inextricably linked to Psycho through the presence of Janet Leigh’s daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis. The scene of her being attacked with a butcher knife in a closed space about the size of a shower stall had only one pop-culture antecedent but a seemingly unending stream of its own imitations. The 1978 Halloween has been followed by seven sequels to date: Halloween II (1981), Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982, the only film in the franchise not involving the Michael Myers storyline), Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers (1988), Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers (1989), Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995), Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998), and Halloween Resurrection (2002). Two remakes using the original titles, Halloween (2007) and Halloween II (2009), were directed by Rob Zombie. A three-part reboot began in 2018 with yet another film called Halloween starring Jamie Lee Curtis, with plans for two additional sequels starring Curtis, Halloween Kills (2020) and Halloween Ends (2021).

Baby boomers are famous for refusing to let go of the sixties and seventies. Laurie Strode, like her original movie audiences, has reached her retirement decade still clinging to her teen years, but with a crucial difference. Hers is a nightmare nostalgia of long-ago traumatic memories that won’t loosen their grip. It’s too bad she can’t just enjoy her films the way we did.

If you enjoyed Halloween (1978), you might also like:

FRIDAY THE 13TH

PARAMOUNT, 1980