THE SHAPE OF SCREAMS TO COME.

The fear of being “taken over” by an outside entity, be it supernatural or extraterrestrial, is a theme that frequently drives both horror and science fiction films, and is often the element that blurs the lines between the genres. For instance, is Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) horror or sci-fi? It’s difficult to tell. Many critics would say it’s both, and audiences are likely not to worry about the distinction so long as the story delivers an entertaining thrill. John Carpenter’s The Thing is an excellent example of a film that serves both genres exceedingly well—even though, on its first release, its unprecedented level of grotesque special effects repelled reviewers and audiences alike. Today, however, the film is widely hailed as a visual-effects milestone in imaginative cinema of the predigital era.

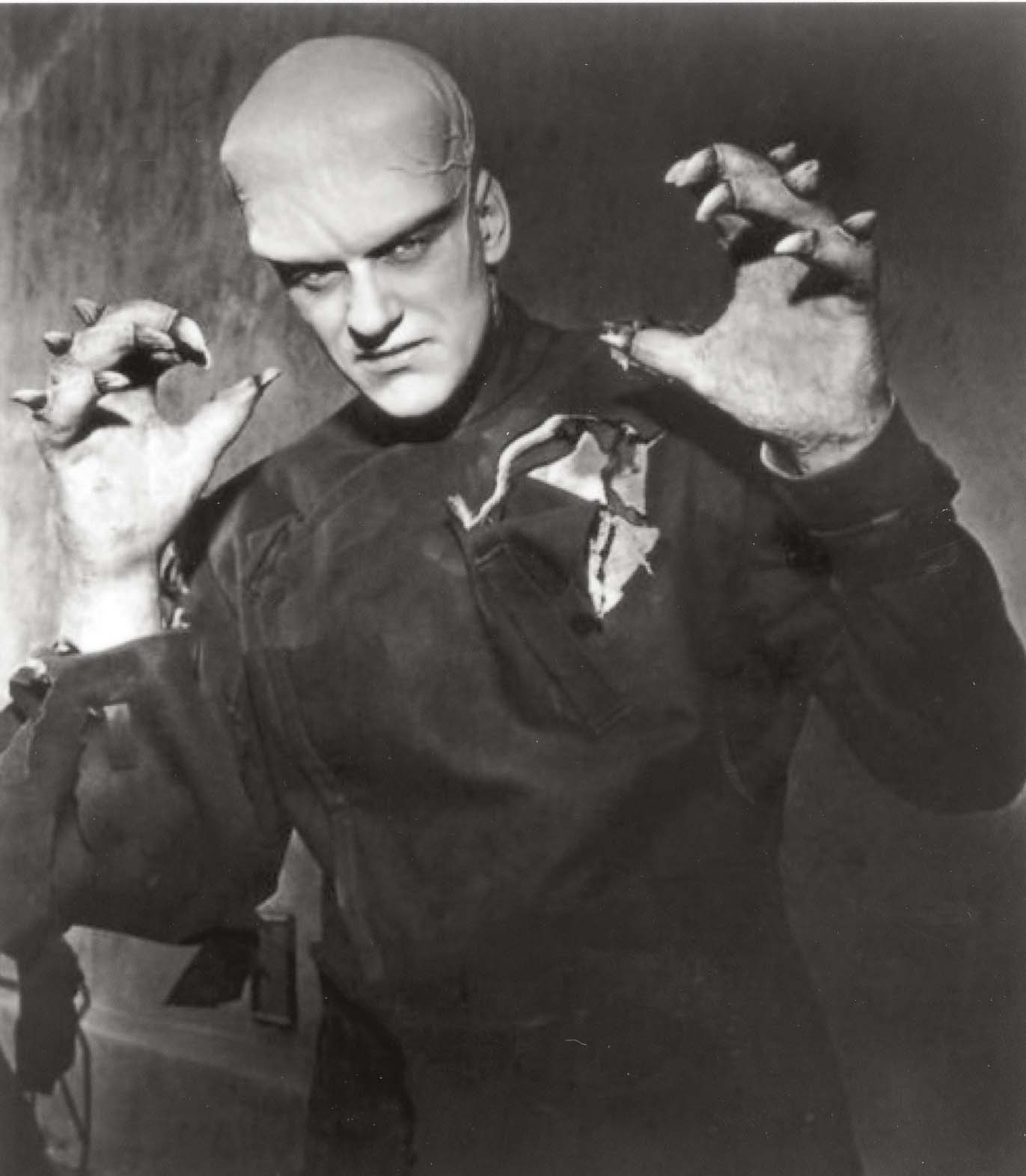

The Thing is based on John W. Campbell Jr.’s 1938 novella Who Goes There? which was originally very loosely adapted to the screen in 1951 as The Thing from Another World, directed by Christian Nyby and produced by Howard Hawks. Campbell’s story is regarded as one of the most influential works of pre–World War II literary science fiction, a claustrophobic tale of an Antarctic research team stalked by an alien life form that can convincingly counterfeit the appearance and behavior of any terrestrial organism, including members of the research crew themselves. A tense guessing game of who’s human and who’s not grips the reader to the climax. Campbell’s influence can be readily detected in paranoia-inflected 1950s films like It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Oddly, the central elements of shape-shifting and paranoia were completely dropped from The Thing from Another World, its alien unimaginatively recast as James Arness in a padded Frankenstein’s-monster costume with lobster-like claws. A proper telling of Campbell’s story hadn’t even been attempted.

A shape-shifting alien entity invades the American base, spreading paranoia among the team. Who is real and who is not? From left, T. K. Carter, Richard Masur, Donald Moffat, and Kurt Russell.

The Thing from Another World (1951) was the first screen adaptation of John W. Campbell Jr.’s novella Who Goes There? James Arness played the alien as a standard movie monster, not a shape-shifter.

Therefore, when Universal acquired the remake rights in 1976, it essentially gained the opportunity to adapt the original story for the first time. The project was first assigned to Tobe Hooper, director of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), but no viable script emerged. John Carpenter wasn’t seriously approached until the huge success of Halloween in 1978 made him a bankable contender. Another box-office hit, Ridley Scott’s viscerally grisly Alien (1979), made it clear that mixing over-the-top physical horror and science fiction might be a winning combination. But Campbell’s story was highly interiorized, with little physical action at all, and Bill Lancaster’s original script kept the monster largely unseen, as in Alien.

Antarctic researcher R. J. MacReady (Kurt Russell) discovers an abandoned Norwegian outpost, destroyed by an unknown force.

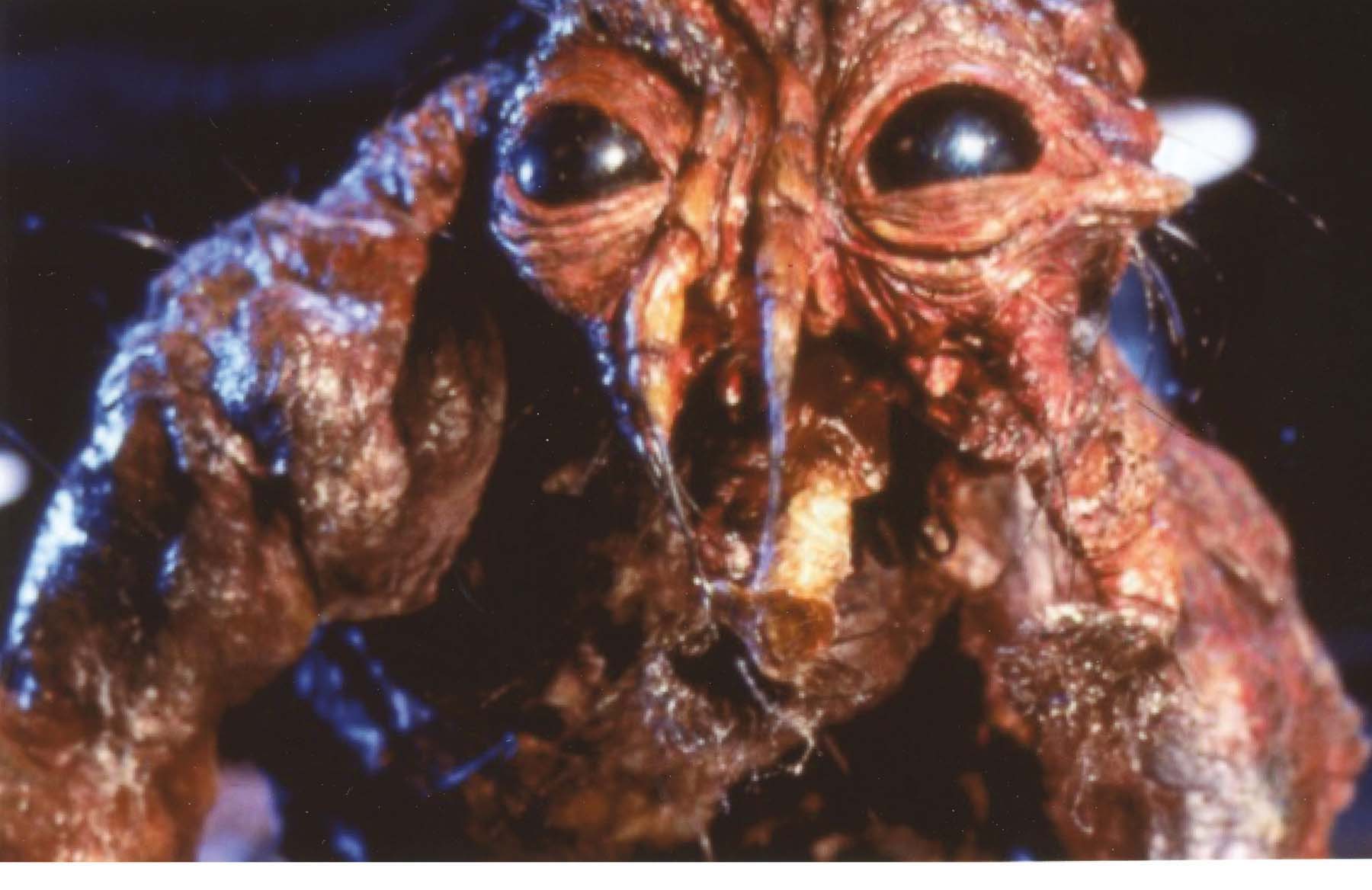

Rob Bottin, who had created special makeup for Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) as well as the werewolf transformations for Joe Dante’s The Howling (1981), urged Carpenter to bring the horror completely out of the shadows. From the time of German expressionism, the grotesque imagery of horror films owed a certain debt to the visual distortions of modern art movements, especially expressionism and surrealism. This influence came to the fore in the 1980s, when special-effects makeup innovations like latex foam made possible infinitely plastic depictions of the human form. Bottin’s morphing monstrosities in The Thing bring to mind Salvador Dali’s melting timepieces given human shape, as well as the ferocious, twisted forms of painter Francis Bacon in works like Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.

Kurt Russell was cast in the lead role of R. J. MacReady; among others considered were Christopher Walken, Jeff Bridges, Nick Nolte, Sam Shepard, Tom Atkins, and Jack Thompson. Carpenter’s completed film followed Campbell’s story with remarkable fidelity, filled out with special effects Campbell could never have imagined. In Antarctica, MacReady and his research team discover a destroyed Norwegian outpost and the charred, frozen remains of a misshapen creature with human internal organs. One of the team’s sled dogs, which had visited the Norwegian encampment, reveals itself to have been absorbed by a voracious alien organism that can take on the shape of any living thing. It may or may not have taken the shape of a team member who spent time alone with the dog, and the thawed, half-transformed humanoid poses a similar threat. It soon becomes difficult to know exactly who is alien and who is not, except when one of the spectacularly gruesome transformations is witnessed. The team is systematically decimated until only a few remain, and none are sure of the others’ true nature.

The larger cultural import of visceral Grand Guignol–esque spectacle in late twentieth-century cinema has been extensively analyzed and debated, but it is likely that at least some of the appetite for blood and guts arises not from sadism but rather from the need to reaffirm the body in all its messy biological reality against the onslaught of the cold technology that engulfs us. In movies like The Thing, nobody is a computer inside. We see the proof.

Special-makeup-effects artist Rob Bottin’s shape-shifting creations for The Thing subjected the human body to a nearly surreal level of stress and distortion.

If you enjoyed The Thing (1982), you might also like:

THE FLY

20TH CENTURY FOX/BROOKSFILMS, 1986