After a brief holiday, I left home in August 1964 to report to the Maratha Light Infantry Regiment Centre (MLIRC) at Belgaum. As the train steamed into the Belgaum railway station, I got into my summer uniform and packed my valise and the black steel trunk. Those contained my only worldly possessions at that point of time. I was received by the duty officer and directed to proceed to the MLIRC officers’ mess. Outside the station, there was no transport waiting for me. So the coolie carrying my luggage suggested that I take a tonga instead. The mess was on a small hill and the poor scrawny little horse found the going quite tough! The driver had to dismount and put his shoulder to the wheel and push. I paid him one rupee, a princely sum those days, and he left giving me a salaam. Finally, on reaching the mess, the havaldar (sergeant) offered me a welcome cup of tea. When I asked him to show me my room, he smiled wryly and said, ‘No rooms are available and Sir, you will have to make do with a tent!’

One of the mess waiters took my baggage and put it in the tent. It had already begun to drizzle. This drizzle continued for the next three days. I knew of the monsoons but had never experienced anything like this. The low clouds passing around the hills made my abode damp and cold. I sat on my trunk and looked around. The tent was no bigger than a hundred square feet and its interiors were bare; besides a cot and an easy chair, there was a folding table and a camp stool. The only light in the tent was from a single 40-watt bulb hanging by a cable on the centre pole. The uneven floor was covered by light brown coir matting. The attached bathroom was even more luxurious! It was a dingy little tent lit by a ‘hurricane lantern’ (a kerosene oil lamp). The space inside it was barely enough for a commode and a towel stand. For the bath there were two buckets placed in a corner, which was raised from the soil with the aid of a few bricks joined together. It was dry sanitation at its simplest. The commode, humourously also called the ‘throne’ or ‘thunder box’, would be cleaned every morning by a sweeper, and the bath water would drain out into a temporary underground septic tank nearby. The only consolation was that I was not alone; there were a few more unfortunate souls like me living in that tented colony.

I was attached by the Army Headquarters (HQ) to the Regimental Centre till the commencement of the raising of the 9th Battalion, the Maratha Light Infantry (LI), on 1 October 1964. There were many more young officers posted to the centre at that time. A majority of them were emergency commissioned officers. I was the only NDA graduate amongst all of them, and I held a regular commission. In every combat unit, besides the commanding officer, there were two or three field rank officers, a captain and the rest were subalterns. The joke was that if one threw a stone in the air, it would most probably land on the head of a young officer!

Even though our habitat was frugal, more like the rear area of a war zone rather than a peacetime cantonment in the south of India, we enjoyed all the free time we got. We followed a strict regimen and work schedule at the centre – PT with the recruits at 6.30 a.m., followed by breakfast, supervision of the training of budding soldiers, lunch, and then games with the troops, followed by dinner in the officers’ mess. Thrice a week we would have a dinner night – a formal affair for which we had to wear the summer mess kit or the blue patrols in the winter. The menu would generally be a three-course Western meal. The helpings were so small that often we would go to our tents and sleep on a hungry stomach! On all other days, we would cycle down to the club or the town and have a good time. I had bought myself a new cycle, which was the only transport most of us could afford, and that too on monthly instalments. One’s salary as second lieutenant was around four hundred rupees and barely sufficed to keep one’s head above water. Yet we managed to behave like ‘sahibs’ of the Raj period, wearing white sharkskin jackets and black bow-ties with Wellington shoes and spurs for informal mess functions. We used to go to the gymkhana at the cantonment, and made a few Anglo-Indian and Goan friends. We would organize dance parties once in a while, mostly on Saturdays. Everyone pooled in for the food. We were most sought after as we took care of the drinks, and rum was the favourite, particularly the XXX Hercules rum from the army canteen! At one of these ‘dos’ I met an attractive Bengali girl. We became friends. We enjoyed dancing together, particularly the foxtrot, the quickstep or the cha-cha-cha. I had become proficient in ballroom dancing at the NDA. She wanted to learn from me and I agreed to teach her. However, this was when I learnt that she was married, and she became off-limits as far as I was concerned. Shortly thereafter we moved to Naga Hills.

As young officers, after clearing our monthly mess bills and other dues, we were left with very little out of our meagre salary; and by the twentieth day we would be almost bankrupt! What would we have done without our regimental banias? They readily helped to bail out the ‘rank and file’ financially whenever we were broke. Of course, they would take their pound of flesh and never forgot to charge us a hefty interest. But loans were not a problem, and unlike banks the bania never took a holiday or stuck to fixed working hours. It was 24x7 the year round for this tribe.

This petty trader, contractor and private banker all rolled into one has existed as an institution in the Indian Army since ages. We must give credit to the British for this unique invention. We have known of two or even three generations that have served with certain battalions and regiments. The battalion in which I was commissioned forty-seven years ago, has seen three generations of the first unit bania, Har Narayan Aggrawal, who began his trade along with the raising of our battalion. Now his son and grandson run the show. A century or two ago, this breed was among the important camp followers moving behind the conquering armies. Their loyalty, dedication and commitment and the readiness to bear privations along with the soldiers whom they served was indeed commendable, and this tradition continues till date. Of course, the fact that there have been some real sharks also amongst them cannot be denied!

The 9 Maratha LI was raised on 1 October 1964 at Belgaum. The battalion was created from scratch. The first day of our existence was historic for all of us who were present. I had to merely step across from the Regimental Centre at Belgaum to the new unit, and happened to be among the first few officers to join the battalion. First of all, there was a prayer ceremony attended by us, the pioneers. This was followed by a ‘Sainik Sammelan’ (a formal interaction with all ranks) by Major K.L. Awasthi, the second-in-command. The gathering on that occasion comprised a few officers, including myself, some JCOs and about 300 soldiers. It was an unforgettable experience for all of us. Major K.L. Awasthi officiated as the commanding officer (CO) till Lieutenant Colonel M.B. Wadke arrived and took charge of the battalion.

We received orders to move to Nagaland in mid-1965. The battalion moved by a special military train from Belgaum to Dimapur. Though the journey was a great experience, it took us forever to reach our destination. Being a peacetime move, our train was given the lowest priority, even lower than goods trains. The rolling stock or the bogies that formed the train were the worst available and in a poor state of maintainance too. The batteries which ran the lights and fans in the compartments required to be charged very frequently. We would spend hours sweating it out in the oppressive heat and unbearable humidity. Nights were comparatively cooler but often without any lights.

For a youngster like me, it was the strangest train journey. The train was the mobile home for 800 troops for over ten days. The officers had a first-class compartment, the junior commissioned officers were given a second-class one, and the rest of the train comprised third-class bogies. Ordinary covered wagons meant for goods were converted into kitchens. The conditions inside these metal boxes were hot as hell, perhaps a shade worse than the boiler room in a steam ship. We really marvelled at the capacity of the cooks to be able to make food in such horrible conditions. We had meal halts and also technical halts for the engines to be changed or refuelled. Sometimes, we had unscheduled halts to allow higher priority trains to pass. At major stations we would get fresh rations and huge blocks of ice for cooling our compartments. Air conditioners were unknown in those days.

We had installed a 20-line field telephone exchange and telephones for key officers and the engine and the guard at the end of the train. Wherever we got an opportunity, we would go for a jog on the platform or the railway siding. The officer commanding of the train had entrusted me with the most thankless and enervating task of keeping a detailed record of all halts on this long journey. Therefore, I had to be on my toes 24x7 throughout the journey to maintain this log. I couldn’t sleep peacefully either during the day or night. I had a few additional hands to help me in this task. Eventually, after many days, we reached Guwahati after crossing the mighty Brahmaputra over a very long bridge. This dual-purpose bridge had two decks, the lower one for the railway and the upper deck for the highway. The bridge was an engineering marvel and was reportedly constructed by Indian engineers. Though work on it started in 1958, the foundation stone was laid by Jawaharlal Nehru in January 1960 and it was commissioned in June 1963. Prior to that, the trains terminated at Amingaon on the north bank of the river. From there, the passengers and baggage were transferred into huge steam ferries and taken to the south bank, where there was a railway terminal at a place called Pandu, near Guwahati.

From Guwahati to Dimapur in Nagaland, the railroad passed through thick tropical forests. We had heard of trains being stopped by the insurgents by felling trees across the track and by firing at the coaches. Therefore, we were ordered to be in combat gear with weapons at the ready, prepared for any eventuality! At times, when the train stopped dead in the middle of a forest, we were told that there was a herd of wild elephants on the track; hence we could only restart our journey once they moved back into the jungle. Finally, we reached our destination – Dimapur – and the battalion detrained on a railway siding. We were piped in by pipes and drums of a sister battalion, and warmly welcomed by a reception committee from 81 Mountain Brigade. It was a huge effort to unload everything, specially the arms and ammunition and other controlled stores. After a thorough check, an ‘OK report’ was rendered by all the company commanders to the CO. Over the next few days, we were inducted by road into our area of responsibility in Phek, ahead of Kohima.

As the monsoon had already set in, the roads were in a big mess. There was only one major artery connecting Dimapur to Kohima and Imphal. Besides this highway, there were hardly any other black-topped roads in those days! Beyond Kohima it was a dirt track fit for vehicular traffic only in fair weather. In the event it had turned into a quagmire of slush. The wheels of the trucks had made ruts that were two feet deep at places. We had a few cases where the vehicles skidded off the road and fell down the hill. Fortunately, we had no casualties and were able to recover the vehicles as they were saved from going too far down the slope because of the dense forests. The battalion took over a week to settle down and the companies moved forward to their posts over the next ten days or so.

Since there was a ceasefire between Naga rebels and the government in force during that period, we had no armed encounters with the hostiles. There was an uneasy peace prevailing at that time, and seven rounds of talks had taken place between the Government of India and the underground ‘Naga Federal Government’. Besides that, there was a peace mission established that was playing the role of a mediator. It had a peace centre and an observer team in Kohima. Dr Aram, a Sarvodaya worker, was one of its prominent members. Taking advantage of the ceasefire, we used to carry out a lot of patrolling to familiarize ourselves with the area of our operational responsibility. I was the intelligence officer (IO) and therefore my work station was at Phek. Whenever the CO moved out for operations or reconnaissance missions it was my task to accompany him, and look into the coordination aspects. Besides, the IO generally functioned as an understudy to the adjutant of the battalion, and as per the normal practice, took over that appointment in due course.

It was on one of these reconnaissance missions that I accompanied Lieutenant Colonel Wadke to the Indo-Burmese border area, about ten kilometres ahead of one of our company posts at Khanjangkuki. The trek to the top of the mountain was one of the most fascinating climbs of my life. We walked along a foot track from Khanjangkuki to the border along the Patkai mountain range. This area was known as the Somra Tract and had a very dense rainforest cover. I had never seen forests like that before. There were tall trees with a canopy branching out on the top and with very little undergrowth. One could not see the soil as the ground was covered by a soft and moist carpet of dead leaves and decaying branches of fallen trees which had lichen and fungi all over. All of a sudden my eyes fell on a ground orchid in full bloom.

This was the first time I had ever seen orchids in the wild. It was a stunningly beautiful sight. We bivouacked for the night in this area and returned the next day to Jessami, the road head. From there we drove back to the Battalion HQ at Phek. The CO did not share with me the reason for this reconnaissance trip. The track we followed had witnessed the Japanese cross the Chindwin river and advance to Kohima during the Second World War. After their defeat in the Battle of Kohima, the British Indian Army under General (later Field Marshal) W.J. (Bill) Slim chased the Japanese back over the Patkai range into Burma.

While we were camping in the forest, we received a wireless message that a vacancy for the intelligence course had been allotted to the unit, and the name of the officer detailed to undergo the course had to be communicated to the Brigade HQ without delay. I was able to prevail upon the CO and get a decision in my favour. As I was functioning as the IO of the battalion, I felt it would be appropriate if I was nominated for it. This decision of Lieutenant Colonel Wadke had far-reaching consequences in my life. Yet it might also have caused some heartburn among others who wanted to do the same course. I attended the course and topped it despite being the juniormost, and later on was posted as an instructor at the Intelligence School at Poona in 1970.

As young officers we were unaware of the political developments in Nagaland, and confined ourselves to the limited realm of doing our assigned duties in the battalion. We had to carry out a number of long-range patrols in order to get to know the area, just in case the ‘ceasefire’ with the Naga underground got abrogated. As good regimental officers we shared the hardships with the men and did our best to be their role models. Sometime during 1966 the battalion got orders to be deployed closer to the border with Burma, with company and platoon posts being established all over in the Tuensang district. We became experts in creating infrastructure and rudimentary habitat with bamboo and grass. Most of these new posts were maintained by air. We became adept at using the cotton parachutes to line the interiors of our thatched shacks, so as to protect us from the rain and cold breeze. We learnt that a large group of Naga rebels, including many young recruits, had crossed over to Burma under self-styled General Thinoselie and other leaders of the Naga underground. They were reportedly headed for Yunan province of China to receive training and arms. It was very interesting to know that this group had crossed over from the area where we were now deployed and that they were given traditional feasts with mithuns (semi-domesticated animal of the ox family) being slaughtered, and local drinks like madhu, a variety of rice beer, flowing liberally.

The year 1967–68 was momentous for all of us serving in 8 Mountain Division in Nagaland. Intelligence reports had confirmed that in December 1967, another large gang of Naga underground rebels, led by self-styled generals Mowu Angami and Zuheto Sema and stalwarts like Isaac Swu and T. Muivah, had gone across from the Tuensang area of Nagaland to China, for training and procuring arms. This was a blatant violation of the ceasefire policy. Over 300 young men had been recruited from the Angami, Sema, Ao and Tangkhul tribes for this mission. ‘Thinoselie, who had gone to China in November 1966, began his return journey in mid-January 1968. He brought with him more than 400 Chinese weapons, including a few mortars, machine guns, rocket launchers and wireless sets, mines and ammunition. Naga tribes living on the Burmese side of the border helped Thinoselie enter Nagaland.’1

The government and the Army HQ were livid with Eastern Command and 8 Mountain Division, in particular, for not being able to intercept and prevent this huge group of rebels from exfiltrating across the border into Burma, and thence to China. Neither were they able to catch Thinoselie’s gang on its return. ‘By April 1968 it had become clear that Mowu Angami and his gang were planning to return to Nagaland in the near future.’2 Hence, 9 Maratha LI was moved from Phek to Kiphire near Tuensang. We reinforced the thin deployment of 8 Assam Rifles along the border, and were placed under the command of 162 Mountain Brigade commanded by Brigadier A.S. Vaidya, MVC. Some other battalions were also moved to plug the gaps in this border area.

The general officer commanding-in-chief (GOC-in-C) of the command was Lieutenant General Sam Manekshaw, and Major General N.C. Rawlley was our divisional commander. A warning was sent out down to the battalion level that the heads of the COs and the company commanders would roll in case the Chinese-trained gang managed to slip into Nagaland undetected this time. With the guillotine facing us there was tremendous tension in the air. Lieutenant General Manekshaw was looking at becoming the army chief and similarly, Major General Rawlley knew his future depended on the level of success that would be achieved by his division in neutralizing the infiltrating gang. Lieutenant Colonel K.L. Awasthy, our CO, also had a nagging suspicion that he might face the axe if we did not perform as expected or if the commanding general had his way, since he didn’t appear to like his face! But we had a great team of youngsters like Baban Shinde, M.N.S. Thampi and D.B. Shekatkar, and we strove to ensure that the battalion or our CO was never let down. We built up strong bonds with the tribes of the border areas, like the Yimchungers, Noktes and Wanchoos. That rapport was one of the primary reasons for our success subsequently.

This was achieved by our exemplary conduct and people-friendly activities. While the insurgents were away from Nagaland for about a year, the security environment of the remote Indo-Burmese region in Tuensang district changed drastically. There was much greater presence of the army along the border and more effective surveillance. Besides, we had won over the hearts and minds of the people. A mistake made by the leaders of the insurgents was that they had included very few men from the border tribes, whom they considered inferior to their own tribes from the heartland. That attitude hurt the pride of these border tribes. As a result they willingly cooperated with us and provided very valuable information and logistical help where required. News kept trickling in of the return of the gang led by Mowu Angami, Issac Swu and T. Muivah. But the question on everyone’s mind was when, and from where, will they re-enter Nagaland? We were palpably nervous and anxious.

On 2 or 3 March 1969, I was asked by the CO to take out a patrol and go right upto the border on the top of the Patkai range, carry out surveillance, and try and get some specific information on the gang. I left for my mission by the afternoon with a mixed group of soldiers from my battalion and 8 Assam Rifles. Very early the next morning, we reached the highest point of the mountain. There the track meandered on a plateau covered with a thick forest. It was a kind of a ‘no-man’s-land’. As we crept forward, the track began to descend sharply. I wasn’t sure of our position, and besides, in those days, we had no GPS to help us out either. Going down the steep slope in the jungle as silently as we could, we suddenly heard noises. We froze at once. I went up to the leading scout and, from the cover of a large tree trunk, saw an incredible sight. There were about fifteen to twenty armed men. It was difficult to make out whether they were Burmese Army soldiers or members of the insurgent gang! I had about ten soldiers and most of them were from Assam Rifles. There was no possibility of ascertaining the identity of these aliens. Further, if they noticed us they wouldn’t let us get away unscathed. In such a situation the one who spotted the adversary first, had all the advantage. In this case not only were they unaware of us but we were also on higher ground and thus dominating the area. I had to make up my mind quickly. Ultimately, it was us or them! I took a calculated risk and decided that if the group moved up the hill towards us, we would open fire, and if not, we would wait and watch. There appeared to be no other option in that fog-covered and densely forested environment of the Patkai range.

Fortunately, they fell in and after checking their weapons and equipment in an orderly manner, started moving back. This was an indication that they were from the Burmese Army, and I heaved a sigh of relief. Had they moved towards us, it could have resulted in an unsavoury incident, a firefight with international ramifications, and probably the end of my military career! That incident would also have spelt doom for our CO as the buck would have stopped at his level, and consequently, a serious setback for our unit.

Even to this day I get the shivers when I recall the events of that dawn. I had a local guide whom I then despatched, with some rum and cigarettes, as my emissary to get some news of the gang. In fact, he actually followed the Burmese patrol till they reached their post. Waving a white handkerchief he approached them and handed over the gifts. He was then told by the Burmese that a large Naga gang had been chased across to our side the previous night. He thanked the Burmese post commander and returned posthaste to the place on the border where I was waiting for the news. Having got the vital information, we literally ran back to the Battalion HQ, believing we had ‘breaking news’. On reaching Anutangre, I briefed Lieutenant Colonel Awasthi on the map, and gave the news obtained from the Burmese Army. He appeared preoccupied and was not greatly enthused with the inputs I had brought. In fact, our troops had been informed by the villagers of the presence of jungle ‘manus’, a local terminology for the insurgents, and were already in contact with them at a few places. He told me to coordinate the ongoing operations and function as the adjutant.

There had been a few encounters in the past twelve hours. As a result of that the gang broke up into smaller groups and tried to get away through the dense foliage. As we were more familiar with the area, our battalion was given the task of combing the dense jungles. Therefore most of our officers and men were tasked to search the jungles as subunits or special mission patrols. Additional units were moved into this sector and deployed on the ridgelines. They became the anvil and we acted as the hammer. This was to ensure that we captured the whole gang. We did our best to ensure that none of them was able to escape from the dragnet. Since the insurgents were not giving a fight, while fleeing they ran into the ambushes along the ridgelines, and the troops deployed there captured them and took the credit. But the real slogging was being done by us.

In one encounter, we had killed some of them but we lost one soldier. The first insurgent we caught was quickly brought to the Battalion HQ. As the officiating adjutant, I was the one who did the preliminary interrogation. The insurgent, a Sema lad who looked barely in his teens, was carrying a sack that weighed no less than 30 kilograms, and had been walking for days on end. When I saw the arms and munitions he was carrying, I was shocked. It could have been a metal pack. Surprisingly, there was a small red-coloured pocketbook dedicated to Mao Tse-tung in the pack. There were no rations, only some brown gooey stuff which I was told was opium. No wonder he was famished and fatigued. So the first thing I ordered was a mug of tea and some food for this poor boy, which he devoured as fast as he could. He recounted his story of how he left his village in December 1967 and walked all the way to Myitkyina in Burma, with the rest of the gang. From there they went by road to a place near Kunming in Yunan province of China. There was a training camp where they were given training for a few months. When they first reached there, as recalled by this insurgent, they were asked to pray to their God for providing them with food. So they remained hungry. Only when they praised Mao Tse-tung was food served to them.

My parents after their wedding, in wartime Karachi, 1944.

A content child, 1945.

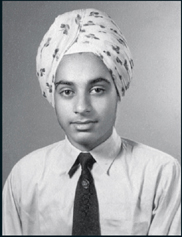

High school graduate, May 1960.

Second term at the NDA, July 1961.

The graduating class with the principal of Model Academy, Jammu, 1960 (I am in the top row, sixth from right).

Sixth term at the NDA, November 1963. Kneeling: Virender Kochhar, Satish Kapur and I; Standing: P. Vig, R.B. Menon, G.R. Sud, CM. Mehta, Captain Surjit Kumar, M.M. Toteja, R.K. Singh and Subhash Kumar.

Raising of 9 Maratha LI, 1 October 1964.

Enjoying a refreshing drink after a gruelling camp, NDA, 1962. First row: Hari Pal Singh, V. Kochhar, Subhash Kumar, K.B. Menon, Y. Malhotra, R.B. Menon, M.M. Toteja, CM. Menta, S. Kapur; Second row: I, P.R. Potnis, K.K. Sainani, S.K. Malik, P. Vig, G.R. Sud, Laxman Singh, T.R. Mullick, A. V. Bhat; Third row: S. Satpute, R.K Singh, N. Menon and G.S. Kahlon (holding the flag).

Adjutant of the battalion, Hyderabad, 1969.

Receiving the Colours for 9 Maratha LI from President Zakir Hussain at Maratha LI Centre, Belgaum, 1968.

Learning to be mountaineers, HMI Darjeeling, 1966.

Delhi Cantonment, 1966. Sitting: I, Veena, dad, mom, Satti; Standing: Bhupi, Inderjeet and Deepak.

Lt Col J.S. Dhillon, the CO 7 Maratha LI, flanked by (left to right) Capt S.L.A. Khan, Maj N.K. Balakrishnan, the RMO, Capt M.S. Shekhawat and I, Tangdhar, Kashmir, 1978.

Tenzing Norgay and I at base camp, 1966 (Mountaineering Course at HMI Darjeeling).

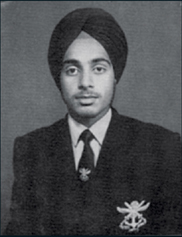

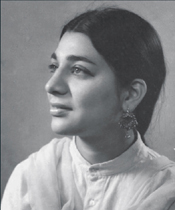

Looking at the future, Anupama (Rohini), 1971.

Elder brother Flying Officer S.J.S. Marwah and his ‘Gnat’ fighter, 1965–66.

Tying the knot with Rohini, 9 May 1971.

Rohini’s parents, Poona, 1948.

Younger brother Lt Col B.J. Singh, a medical specialist in Army Medical Corps, 1993.

Receiving the Vishisht Seva Medal for distinguished service as CO 9 Maratha LI from Gen A.S. Vaidya, MVC8, chief of army staff, Army Day 1984.

With my company commanders: Pritam Bhandral, M.N.S. Thampi and J.R.F D’Souza, and warriors of Tirap, Arunachal Pradesh, November 1981.

Rohini and I with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at Army House, New Delhi, January 1984.

As company commander on the Line of Control, Tangdhar, Kashmir, 1978.

Winners of ‘skill at arms’ championship, Bison Division, Hyderabad, 1986.

Seeking the blessings of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj on taking over the command of 9 Maratha LI, Tezu, Arunachal Pradesh, February 1981.

One of the first surrenders by a militant, Baramulla, 1991.

As brigade commander, controlling operations in Kashmir, September 1991.

A display of arms and ammunition captured during Operation Mousetrap, November-December 1991.

‘For he’s a jolly good fellow, so say all of us,’ Chandi Mandir, January 2005.

Traditional farewell from Western Command – ceremonial buggy of four-in-hand, January 2005.

Rohini and I with the kids – with scary yet regal escorts, Tezu, Arunachal Pradesh, 1981.

Presenting the Colonel of the Regiment Trophy to Col M. D’Souza during the bicentenary celebrations of 5 Maratha LI (Royal).

Rohini and Sonia with a Tuareg tribesman in Sahara desert, Algeria, 1988.

Sonia, Rohini and I, Atlas mountains, Algeria, 1989.

Receiving the Ati Vishisht Seva Medal from President K.R. Narayanan, 2001.

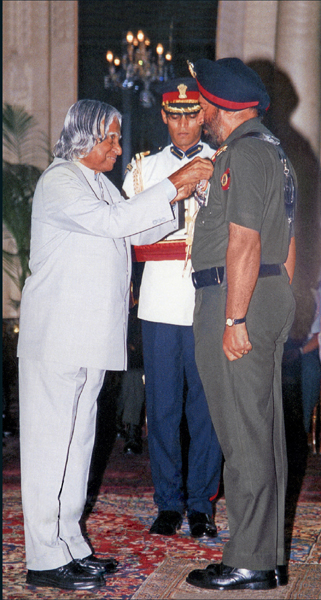

Decorated with the Param Vishisht Seva Medal by President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, 2004.

Talking of his journey back, he said that they were moved in buses upto Myitkyina and then started trekking through the forests of northern Burma towards Nagaland. En route they had a number of clashes with the Burmese Army and even suffered some casualties. They pressurized the Burmese villagers to give them food and shelter, without giving them adequate compensation. Sometimes they went without food and survived on opium. When he was caught by our troops during the first week of March 1969, he was so fatigued that he could not resist or fight, as they had been marching continuously for seventy-eight days. That was the first time we saw an AK-47 rifle, over four decades ago! As soon as we informed the Division HQ about the capture of an insurgent from the gang led by Mowu Angami and Issac Swu, Brigadier S.S. Malhotra, the deputy GOC, himself flew down to our Battalion HQ at Anutangre by helicopter to take him back for gaining as much information as possible, in order to plan further operations. Time was at a premium so he did not stay for more than half-an-hour or so. The brigadier congratulated the battalion for the good job done before he left.

A fine account of this operation has been written in the history of 8 Mountain Division, ‘…. the gang was first located on the international border by the Marathas. It was on 4 March 1969 that a commando platoon patrol of the 9 Maratha LI led by Maj. Y.S. Shinde spotted a large gang near Tinmaung on the border, due east of Zunheboto. Mowu, who could not cross in the Chakhesang country, had moved north, but was not keen to make his way in the Sema-dominated territory. It was later reported that one of his (Mowu’s) men pointed a pistol at him and insisted that he cross at Tinmaung. His men were tired of carrying heavy loads up the hills and down deep gorges in the past couple of months and were keen to get some rest in their own land. They had no footwear, and their clothes were in tatters.’3

Finally, Mowu Angami, the C-in-C of the Naga army, and the rest of his gang were cornered at a camp near Koiboto. Many camps of the underground had already been destroyed by us as the ceasefire had been abrogated by the Nagas by getting arms from China. Mowu’s complete gang was effectively cordoned off by troops of 8 Mountain Division, and nearly a fortnight later they were forced to capitulate. Once they were warned of the serious consequences if they refused, they had no choice but to surrender, which they did. There were 169 insurgents in all, and they also handed over about 100 Chinese-made AK-47 rifles, machine guns, carbines, rocket launchers, stick grenades, pistols and a lot of ammunition that they had brought from China. Mowu Angami was taken into custody. The defence minister, Sardar Swaran Singh, informed Parliament on 1 April 1969 that the security forces had captured Mowu Angami and his gang with their weapons. The prime minister congratulated Major General Navin Rawlley and the troops under him for this signal success. This operation was a great achievement for 8 Mountain Division.

However, Isaac Swu and T. Muivah broke up their group into small parties and managed to escape. Still, many of them surrendered later on. Overall, the performance of 9 Maratha LI during the extended four-year tenure was indeed praiseworthy, and even though we were a young battalion, we made a mark. Major Y.S. Shinde and Naik Balwant Sawant were decorated with Sena medals, and a few more gallant soldiers of the battalion got the chief of army staff’s commendations. We did not have a single case of human rights violation or molestation in an area where the women of the Nocte and Wanchoo tribes, as per their traditions, did not cover their bosoms. We were very proud of our conduct as leaders, and for this we must give credit to our commanding officers who brought us up with a strict code of conduct, and impressed upon us that we were ‘officers and gentlemen’ above all. Lieutenant General Manekshaw, or ‘Sam Bahadur’, as he was fondly called by the rank and file of the Indian Army, was the epitome of ‘the officer and a gentleman’ tradition. He had inspired all of us so much as our army commander that we were ready to do anything to implement his strategy and directions relating to counter insurgency. We had outstanding successes such as the neutralization of almost the entire gang of Naga hostiles led by Mowu Angami. I realized that he was not only a great military leader, but also had many other qualities, such as being lion-hearted, particularly in adversity. He also had an uncanny sense of humour, and seldom lost his cool.

Surrender by Naga rebels, March 1969:

Top: Inspecting the first AK-47 captured by us. Above left: The first Naga rebel captured by us. Each of the rebels was carrying arms and ammunition loads weighing 30–40 kgs. Above right: Chinese weapons captured from a small group of General Mowu Angami’s gang (AK-47, pistol, rocket launcher, sniper rifle, stick grenade, ammunition and mortar bomb).

During this tenure in Nagaland, I did the basic and advanced courses in mountaineering at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI) at Darjeeling under the legendary Tenzing Norgay, Nawang Gombu and Lieutenant Colonel Narinder Kumar. I got an ‘A’ grade on both and was even recommended for a Himalayan expedition. Subsequently, I went to the HMI as an instructor for an adventure course for school children, including a few boys from Australia. I loved the mountains and discovered that I had a natural flair for climbing. Moreover, I could stand high altitudes better than most.

In 1968, our regiment, the Maratha LI, celebrated its bicentenary and was presented the colours by President Zakir Hussain. Each battalion had to select an officer to receive the colours from the president at a presentation ceremony. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have been nominated to receive the colours for 9 Maratha LI by our commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Awasthi. At a glittering ceremonial parade in our Regimental Centre at Belgaum, the colours were first consecrated by religious teachers and priests, and then they were presented to each battalion in turn by the president as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Our older battalions, whose origin dated back from 1768 to 1800, laid to rest their old colours presented by the British monarchs during this parade. In his address, the president said, ‘Your regiment has, during the last 200 years of existence, added many brilliant chapters to the glorious annals of the Indian Army.’

My parents, along with my elder brother, Flying Officer Satti Marwah, and sister Veena had come to witness this historical event. Later, when I took over the command of the same battalion in 1981, it was a rare personal achievement. Not every officer who received the colours that day was destined to command the same battalion.