After a long but successful stay in Nagaland, our battalion moved to Hyderabad for a well-deserved peace tenure. The unit lines were near the Golconda Fort. I had been appointed as the adjutant, which is a key assignment in a unit. Training and sports are the core activities during peace-time soldiering and these kept us busy.

As it happened, I couldn’t stay long with the battalion at Hyderabad and was posted to the Intelligence School, Poona in 1970. I stayed there as an instructor for three years. This assignment played an extraordinarily important role in shaping my military career, and in honing my professional skills and enhancing my knowledge base. In those days we did the General Intelligence Course for a duration of three months. It was called the mini-staff course. The most important thing we learnt was how to do an intelligence appreciation, that is, analyse the various options available to the enemy or adversary and deduce his most likely course of action. Our own plans should only be evolved thereafter. Later, as an instructor, this approach to problem-solving became second nature to me.

The biggest weakness in many of us in the defence forces is that we seldom give adequate consideration to the enemy’s plans; we tend to make excellent plans in which the enemy’s actions are made to ‘fit’ into our scheme of things. Therefore, such plans are likely to go awry when the enemy adopts a course of action that we have not anticipated. In any case, we need to remember that the best of plans hardly survive the first engagement. There must be inbuilt flexibility to modify, change or adopt Plan B to exploit any unexpected opportunity. At the Intelligence School, we also learnt to articulate ourselves with precision and logic, both orally and in writing.

It was also a great posting for me personally, as I met a very charming and talented young lady, Anupama, who was doing her graduation from Wadia College, Poona. We met at the New Year’s dance, fell in love, and got married in May 1971. The circumstances under which we met were quite interesting, and made news when I became army chief. One media account went like this:

The scene was straight out of a movie. Across a crowded room, a young officer saw a beautiful girl escorted by her parents at a New Year’s party at an army club. Most faces looked familiar as only members frequented the club. Only the girl stood out. The curiosity built and the brash captain entered a bet with his friend (Captain Ramesh Bhatia) that he would have a dance with her. The girl refused; and to drive home the message that she was not interested, she went and sat next to her mother to deter the young man. This is what they call an obstacle in military training. Being deft in negotiating obstacle courses, he walked up to the mother and asked her politely if he could have a dance with her pretty daughter. Faced with this impudence what could the poor mother do. And Captain Joginder Jaswant Singh had his first dance with petite Anupama, who became his wife in just a few months.1

Anupama (whom I call Rohini), is also from an army family. Her father, Colonel Narenderpal Singh, was commanding the ordnance depot at Dehu Road, near Poona, at that time. Both her parents are also literary figures. Her mother, Prabhjot Kaur, is a famous poet who has been honoured with a Padma Shri. Her parents are also recipients of the Sahitya Akademi award for Punjabi literature, a rare achievement for a couple. Colonel Narenderpal Singh was commissioned in the Sikh Light Infantry during the Second World War, and served in the Middle East. Later, during the 1950s, he was transferred to the ordnance corps. Rohini soon realized that she had married a professional whose first love was the army. She once asked me what role she had as an army wife. My reply was, ‘the soldiers will give their life for the nation on my orders so you must take care of their families first, and then look after our children and our home’.

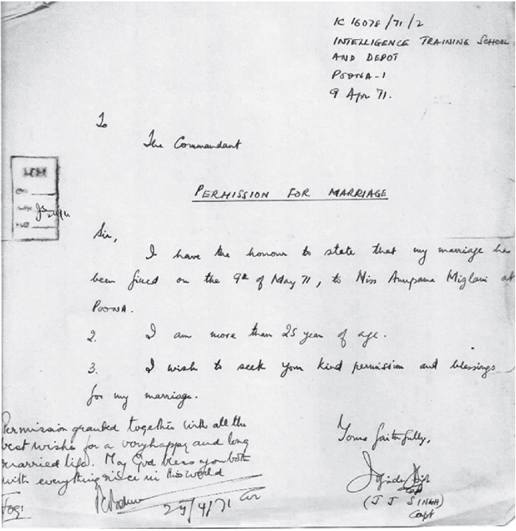

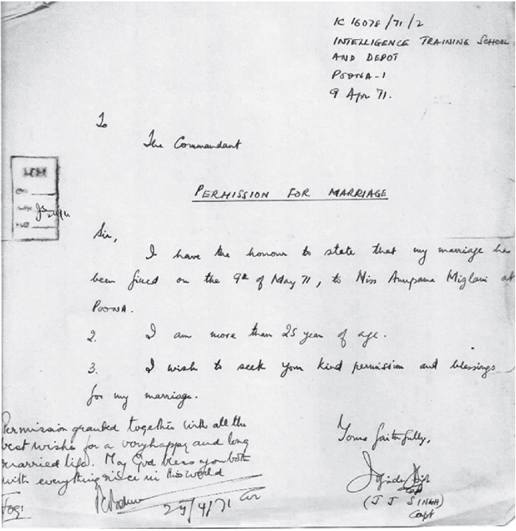

As per army customs, we are required to take permission from the CO for getting married. This was perhaps done to ensure that officers did not tie the knot with the wrong girls. I followed the rules and sought approval (the letter is reproduced below).

My letter to my CO asking for permission to get married.

We settled down in a small house within the precincts of the Intelligence School, and made it our home for two wonderful years in Poona. We had no worldly possessions to do up the house, except the bare essentials. We used ‘matkas’ (earthen pots) to store drinking water and an ice box to cool the fruit and vegetables. Basic necessities like a refrigerator or air conditioner weren’t affordable. Yet Rohini made our home comfortable, and gave it an artistic touch with a minimalistic look. Till she put up her paintings and sketches, I never knew that she was a good artist. She had held her painting exhibition at Bal Gandharva Rang Mandir in Poona a few months before our wedding. Later she told me that she had studied art at Academie Julian in Paris, when her father was posted there as the military attaché in our embassy from 1966 to 1969. As a teenager, she had travelled all over Europe during their three-year stay in Paris. Earlier, as a child, she had lived in Kabul, when her father did a stint as the defence attaché in our mission in Afghanistan. With all her foreign travels and exposure to the advanced countries, I sometimes wondered how she would take to living with an infantry man. To our credit, we made it work, though it was tough.

We are both fond of the outdoors and sports. When we were about to be married, she asked me very innocently, ‘I hope you don’t play bridge or golf.’

‘I do,’ was my frank response. When she asked me to give up these games, we made a deal. I would not play bridge provided she joined me in golf. We have kept our word. We are avid golfers and surprisingly, enjoy playing together. I find golf a great stress-buster.

It was during this period that I received a communication from the Army HQ asking me to report for the pre-Everest expedition trials at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, Darjeeling. Having done well in the basic and advanced courses, I felt I could make it to the Everest expedition if I volunteered. But in that case, my life thereafter might have been that of a mountaineer. When I asked Rohini for her advice, her response was that I should carefully analyse the pros and cons and then decide. Further, she conveyed that she would respect my decision. As it happened, I decided to continue soldiering. Importantly, I also continued to enjoy the mountains while serving at the northern borders along the great Himalayas.

In 1971 Pakistan was going through a political crisis. In the elections to the national assembly, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman, had won a majority by making a clean sweep in East Pakistan, winning 160 seats, whereas Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party won about half that number. Taking a rational view, there appeared no option other than to make Sheikh Mujib the prime minister of Pakistan. As this did not happen, the internal situation in East Pakistan worsened. Eventually, the Bengali people of East Pakistan revolted and on 23 March 1971, independence was declared and Bangladeshi flags were unfurled all over. On the evening of 25 March, Sheikh Mujib declared the creation of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. In a broadcast, he stated, ‘From today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh to resist the army of occupation to the last….’

In an act of vengeance, the same night, the Pakistan Army unleashed Operation Search Light, a ruthless and repressive campaign to subdue the alienated population. Sheikh Mujib was arrested and whisked away to jail in West Pakistan. Hundreds were killed or arrested and many other atrocities like rape and pillage took place. Streams of Bengali refugees, both Muslims and Hindus, started pouring in from strife-torn East Pakistan, which was witnessing a civil war between the ‘Mukti Bahini’ freedom fighters and the Pakistan Army.

As a great diplomatic move, India signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union on 9 August 1971. ‘Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet foreign minister, visited New Delhi and signed this treaty. It was one of the best-kept secrets in Indo-Soviet relations.’2 The most vital and crucially important aspects of the treaty were contained in Articles VIII to XI, ‘which provided for an all-encompassing commitment of defence cooperation and mutual defence assistance in case of either party being subjected to threats to their territorial integrity and security,’ wrote J.N. Dixit. This treaty reshaped the politics and geography of our region.

The intensity of the skirmishes between the ‘Mukti Bahini’ and the Pakistan Army along the Indo-East Pakistan border increased in the later part of 1971, leading to a conflict situation. Open hostilities in the eastern theatre commenced on 29–30 November, and the Indo-Pak war broke out on the evening of 3 December 1971, when the Pakistan Air Force carried out a pre-emptive attack on our airfields, military and civilian targets. The retaliation by the Indian armed forces was swift and massive. All our service training institutions were temporarily shut down, except the training facilities for recruits and officer cadets. I was posted to Western Command and told to report at Jalandhar Cantonment, where the operational headquarters of Western Command had been established. I worked in the intelligence branch, which, as usual, was one of the most hard-pressed. Everyone wanted to have the latest information. It was a thankless yet challenging task to meet the demands of the Corps and Division HQs. In a short-duration war, real-time, hard and actionable intelligence is difficult to come by. But we tried our best.

Eventually, in the eastern theatre, the Pakistan armed forces were inflicted a crushing defeat. In a brilliant campaign, the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force, ably supported by the Mukti Bahini, the paramilitary forces, the BSF in particular, and people on both sides of the border, liberated Bangladesh. On 16 December 1971, the Pakistani forces formally and unconditionally surrendered and a new nation emerged. Bangladesh became a reality. For this brilliant land campaign, the credit rightly went to the armed forces leadership, in particular the army chief, General Sam Manekshaw; the GOC-in-C Eastern Command, Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora, his corps and division commanders and all other subordinate commanders and staff officers. I do not subscribe to the exaggerated claims for a larger-than-life role played by some other senior staff officers. We must not forget that in the defeat of 1962, the heads that rolled were of the army chief, the corps commander and other leaders, and not of their chiefs of staff or other advisers. The ultimate responsibility and accountability of achieving the mission rests on the shoulders of the commander concerned. On the western front, on 17 December 1971, a ceasefire was unilaterally declared by India and accepted by Pakistan. India had won a decisive victory, and we took 93,000 prisoners of war. It was one of our best-fought wars. The nation celebrates 16 December every year as Vijay Diwas.

After the war was over, I returned to Poona and resumed my duties. Soon I was ordered to proceed to Dhana, a small military station in central India, where we had set up a camp for Pakistani POWs. I was assigned to interrogate the important POWs. There were almost a thousand prisoners in that camp. It was very interesting to hear their account of the war. There were some who did not reveal anything more than their name, rank and unit, and kept shut. There were many others who, when engaged in a conversation, revealed everything they knew. There was a third category of POWs who were angry with their leadership and their generals who had put them in this mess and brought humiliation to Pakistan. They were the most forthcoming. I remember one of them telling me that we Indians didn’t even know ‘how to kill’ someone properly! I did not realize the import of his statement at that time. (Three decades later, when a few of our soldiers’ badly mutilated bodies were returned after the Kargil War, these words flashed back in my memory.)

All 93,000 Pakistani POWs were treated fairly by us as laid down in the Geneva conventions. No third-degree methods were employed, as there were strict orders to that effect. There were many families in the station, particularly the ladies, who wanted to see the Pakistanis. I remember one middle-aged major who was the second-in-command of 31 Baluch, an infantry battalion that was defending Jamalpur. In his diary he had recorded a graphic description of the battle of Jamalpur, of how brilliantly the Indian Army engaged them frontally, while they cut off the rear by placing an effective road block. Thereafter, the Baluchis were attacked from the exposed flanks and the rear where their defences were weak and uncoordinated. I asked him, ‘How is it that you lost so badly?’ He replied that it was because the ‘awaam’ (the public) was against them and that this was also due to good leadership displayed by the Indians. This gallant action was undertaken by 1 Maratha LI (Jangi Paltan), led by Lieutenant Colonel K.S. Brar, who was decorated with a Vir Chakra for this operation. The battalion got a large number of gallantry awards for this action and most importantly, the ‘battle honour’ of Jamalpur. I gave a brief of this historical account to Lieutenant Colonel K.S. Brar, VrC, while doing the staff college course in 1976, as he was my instructor at Wellington.

After two months or so at Dhana, I returned to Poona and it was once again back to the normal grind. Like me, most of my colleagues had served for eight to ten years, and we all aspired to do the Staff College Course. The entrance examination was in February 1973, and as is the norm, all of us were hopeful of doing the pre-staff course and taking leave to study for the exam. However, the commandant of the Intelligence School, Colonel Balakrishnan, was faced with a dilemma. How could he run the institution with five of his instructors being away? Therefore, he gave a ruling that none of us would be given leave or a chance to do the pre-staff course. Now it was up to us to decide whether to sit for the exam or not. Practically all of us accepted the terms of reference and took the exam from the ‘line of march’, so to say. I appeared for the Part ‘D’ promotion exam in November 1972, and two months later sat for the Staff College entrance exam along with the others. In between both these exams, our son, Vivek, was born on Christmas day, a little after midnight. When the results came out in May or June 1973, out of five of us, three had qualified in the examination, including me (the other two were Captains S.S. Mehta and Satpal Sandhu). I proved to be the dark horse, the only one to get a competitive vacancy (amongst the top twenty in the order of merit). This tenure was professionally and socially very stimulating and active. We were a young and energetic team of instructors in the process of enhancing our professional knowledge, and had a good circle of friends.

On completion of my tenure, I was posted back to 9 Maratha LI. The battalion was stationed in Malari, a high-altitude area on the Indo-Tibet border, beyond Joshimath. My stay in the ‘paltan’ was shortlived as I was required to join the Staff College at Wellington in January 1974. My daughter, Urvashi (also called Sonia), was born in Delhi just before we moved to Wellington.

The Defence Services Staff Course was an enriching experience as for the first time, I had an exposure to a tri-service and an all arms and services environment. Besides, one got to meet and interact with some of the brightest brains of our armed forces as also those from friendly foreign countries. We were taught how to analyse a problem in a logical and pragmatic manner and to express it succinctly in writing or orally. The art of problem-solving in a focused way and in a compressed time frame was something that has remained with me ever since. Being one of the juniormost and among the first few in my batch on the course, I was fairly disadvantaged as I had no ‘previous course knowledge’, famously known as PCK. Many senior guys on the course were well-armed in this regard. They played golf or partied after submitting their solutions in good time, whereas I would be tearing my hair and struggling to finish my work till the last minute, with the directing staff breathing down my neck. There was a lot of sporting activity as well as a hectic social life at Wellington. It was one of the best periods of my life. We actually practised the maxim ‘work hard and play hard’. We made some lifelong friends and this association has stood me in good stead all my life.

The year in the Staff College passed very quickly. Before we knew it we were packing our bags. Rohini and the kids moved to Delhi and I to New Mal, a godforsaken little non-family station in the Dooars of North Bengal, as the brigade major (BM) of 123 Mountain Brigade. Our formation had the task to defend our border in the eastern theatre. When the postings were out, a lot of my friends pulled my leg saying, ‘JJ, it’s good you are going as BM to “Stiffy” Vadehra. He will sort you out, nice and proper.’ Brigadier P.S. Vadehra had a reputation of being a hard taskmaster, a thorough professional and a fitness freak. He was a soldier who had a vice-like handshake.

When I reported to him, he sized me up and his first remark was, ‘Where did you get these fancy shoes from?’

I was taken aback, but not unnerved, and replied, ‘These are authorized pattern brogue shoes, Sir.’

‘But don’t you know that we are a mountain brigade?’

‘Yes sir, I do,’ I said, looking at the big boots that he was wearing. I got the message. Thereafter, not only did I procure the boots but also the ordnance pattern socks that our soldiers wore!

We had an important brigade-level exercise in a high-altitude area in Sikkim. During the exercise we were rehearsing our operational role. At a critical juncture, the brigade commander’s wireless operator collapsed and there was no one to carry the radio set. It was raining and freezing cold. I remained cool and just picked up the set and strapped it on my shoulders. I told the COs I was manning the radio set, and that it would help if they responded when I called. The command and control was more effective this way. The exercise went off well, and Brigadier Vadehra was more than happy. Thereafter, I couldn’t do any wrong. After a few months, we were permitted to bring our families to the station. So I asked Rohini and the children to join me. We lived in a bamboo-walled structure with a roof made of CGI (corrugated galvanized iron) sheets. Wherever we have lived in the last four decades since our marriage, Rohini has made the house into a home. One night the whole thing was shaking and we felt as if there was an earthquake, only to be told that there was a herd of elephants around and that we should switch on our lights and not venture outside. We were also told that our Brigade HQ was located in the middle of an elephant trail, so they had the right of way.

Once we narrowly escaped being trampled by a rogue elephant. This incident took place when we were travelling in a jeep to Siliguri. Seeing many vehicles crowded at a point, the driver slowed down. I presumed that there had been an accident and told the driver to press on. As he did so, the jeep came to a halt after about a hundred yards. As the driver got down and lifted the bonnet, we noticed a wild elephant advancing towards us from the forest. We just froze, me on the front left seat and Rohini, the kids and a maid at the back. The elephant had come so close that we could smell his body odour. Suddenly the driver began to chant ‘Jai Ganesh, Jai Ganesh’ quite loudly. When I thought that we had just about had it, the rogue elephant turned around and retreated into the thicket. I looked back and saw people watching the drama. Somehow the jeep started and we quickly drove off, thanking our stars.

Our relationship with Brigadier (later Lieutenant General) Vadehra and Taran Vadehra, his very warm and affectionate wife, remains very close even today. He made me into a tougher soldier. After a year or so, there was a change of commanders, and Brigadier N.K. Talwar took over. His was a different leadership style – softer and yet fairly effective. I noticed that several people tried to cosy upto Brigadier Talwar and said a lot of things to please him. I didn’t change my colours and my loyalty to the previous brigade commander, while being equally loyal to the successor. Brigadier Talwar, an exceptional professional, was mature enough to see through it all. He was very happy with my work and I continued to contribute towards the operational effectiveness of the formation, with his guidance. We also have a wonderful relationship with Nikki and Kusum Talwar, and we have kept in touch ever since. I learnt a lot from both of my brigade commanders.

On completion of my stipulated tenure of two years as a brigade major at New Mal, I was posted back in February 1977 to my battalion 9 Maratha LI, which was located at Jalandhar Cantonment. It was nice to be back home – back to regimental soldiering. I was appointed as ‘A’ Company Commander. In no other command assignment is an officer closer to his men than in this post. Our focus was on training, administration and sports. The aim of every company commander was to win the inter-company championship trophy. Every tournament we played was like a battle. Even the ladies and children joined in to cheer up the teams. Vivek and Sonia, my son and daughter, would always take on the mantle of the ‘screaming brigade’, and be the cheerleaders. The battlefield was the Katoch Stadium. Nearly twenty-eight years later, on the same sports field, I would address a ‘Sainik Sammelan’ of 11,000 officers and men of 11 Corps, led by Lieutenant General P.K. Singh, an outstanding leader. Such a large gathering was some sort of a record. I was the army commander of Western Command and the chief of army staff-designate at that time. It was a very moving event for me.

We did well in many of these sports and professional competitions. I was able to train and motivate my company to a high pitch. Our focus was to be the best company of the battalion and we worked very hard to achieve our objective. Consequently, ‘A’ Company won the championship trophy for the year 1977. My sole aim was to earn the respect of my men and be remembered as one of the best company commanders. ‘B’ Company under Major M.N.S. Thampi was the one that gave us the toughest competition. Six years later, he succeeded me as the commanding officer of the battalion. One interesting aside during this tenure was that I nearly got assigned on the five-month-long battalion support weapons course. There was a vacancy on the course allotted to our brigade, and there was no junior officer available to go for it. Since surrendering of a course vacancy was not acceptable to the higher HQ, my name was forwarded. It was really a joke for someone who had done the Staff College and been a brigade major for two years, to be sent for this course meant for captains and lieutenants. All because I was below thirty-two years of age! Somehow, wisdom prevailed at the Division HQ and I was taken out of this assignment, although for me it would have been like a paid holiday.

Unexpectedly, the next summer I got a posting to a remote field area in Jammu and Kashmir, in the Tangdhar sector. It was graded as a ‘high-altitude and uncongenial climate’ area. I did not think it fair to be sent to an operational area once again, but I was told that 7 Maratha LI needed officers of my seniority to command companies deployed along the line of control (LoC), as the posted strength of officers in the unit had become very low. Some had been declared medically unfit and had to be moved out of the battalion. Therefore, during mid-1978, after the usual farewell dinner, I moved to join 7 Maratha LI. My wife and kids stayed behind at Jalandhar. This was my first posting to the LoC in J&K.

The overnight train journey to Jammu was uncomfortable because of the hot and muggy weather. From there it was a gruelling three days’ journey by road to Tangdhar, a distance of about 250 kilometres. The movement beyond Jammu was in a controlled convoy system, with scheduled halts at the transit camps en route. After a night halt in a beautiful transit camp by the side of the turbulent Chenab river at Ramban, I reached Srinagar the following day.

The rundown transit camp at Srinagar could be made out even at a distance of half a kilometre, by the bluish grey smoke emanating from the coal-fired ‘bukharies’ being lit in the evenings, particularly during the winter. The fine soot of these heating devices had, over the years, coated everything in sight black. The faces and hands of the bearers and other workers in the camp had been darkened by the smoke. It reminded me of the poor chimney sweeps I had read about, while in school. Pollution and degradation of the environment at its best, I mused.

The next day, after a tedious and tiring journey on an even more potholed road, the convoy halted at the logistics base for the troops serving on the LoC. During the winter the journey beyond had to be on foot or by helicopter due to the enormous amount of snow on the Shamsabari range. Because of the danger of avalanches, the next stage of the journey, to the Nastachun Pass and beyond into the valley of Tangdhar, had to be undertaken at night. The steep snowy slopes were comparatively stable during that period.

After a refreshing mug of tea at the pass, we proceeded ahead and reached the Battalion HQ in the evening. I was welcomed by the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel J.S. Dhillon. The next day, I was formally interviewed by him and ‘dined in’. From the Battalion HQ to my company piquet it was a strenuous uphill trek of about two hours. My post was at an altitude of about 8000 feet. I was received there by the subedar sahib and shown around. The barbed-wire fence and the skull-and-bones warning boards inside the minefield indicated the LoC. The proximity of the adversary could not be taken lightly.

After the formal briefing, I entered my bunker and had a hot bath. The water was stored in an improvised bucket made from an empty oil tin with a wire handle. It relaxed me as much as a tub bath or a shower in a five-star hotel! The bunker was heated by a bukhari. The warmth exuded by the burning wood was very comforting. I knocked down two quick shots of rum and some appetisers comprising fried liver, pakoras and namkeen. For me, in that wilderness, it was the equivalent of champagne and caviar!

The company commander’s bunker was a huge dugout of about 200 square feet with a small bathroom adjacent to it; it had a ceiling made of wooden logs with about twelve inches of sand bags and earth placed above to give it protection from shelling. It had walls made out of planks of the deodar (pine) trees, which were plentiful in that area. It had an agreeable fragrance of old wood, quite like some high-end perfumes. I wondered if it could withstand a direct hit of an artillery shell. But then I wouldn’t be in it, as during a hot war I would be directing the battle from the command post – a fortified fighting bunker.

The next morning was bright and clear. Coming out of my bunker, I was stunned by the landscape. What a glorious welcome. As the sun rose over the Shamsabari range, the ultraviolet rays reflected off the snow-covered higher reaches, and directly hit the retina. I shouted for my snow goggles, and wore them over the balaclava. I loved the feel of the goggles and the soothing effect they had on the eyes.

At places the LoC went along the Kishanganga river, with villages on both sides of the river divided by an artificial line. Entire families had been split into two. Elsewhere, the boundary followed the ridgeline or went midway between the top and the valley, cutting across the mountainside. This created complications of its own. The countryside was peaceful and tranquil and the people were mostly poor farmers. They looked for jobs with the army so that they could have a steady income. Though the area was incredibly beautiful, because of its remoteness, there were hardly any visitors or tourists. It was famous for its walnuts, whose outer cover could be crushed by hand. They are commonly called as the kagazi, a paper-thin variety.

The task of my company was to defend the assigned area along the LoC. For that we had to maintain an elaborate observation system to keep a watch all along the border. The daily routine on the post involved, besides the surveillance of the border, morning and evening ‘stand-to’, patrolling and the laying of ambushes to prevent intrusions, and the improvement and maintenance of our defence works. Occasionally, I would order stand-to or alert at odd times to test the readiness of my troops to get into battle positions quickly. Every morning, I would go around the company-defended locality and meet with the soldiers, and then attend to the administrative issues and some office work. Later, after lunch, I would play basketball or volleyball with the men. I got to know each of them well in a short time. Life was lonely as I was often the only officer on the piquet. There were no means of communication except the field cable and antiquated telephones for communicating within the battalion and with the units on our flanks. Letters were awaited eagerly and Rohini and I would write to each other regularly. But letters usually took longer than a week or even up to a fortnight to reach. Sometimes two or more letters would arrive at the same time, and it was fun to decide which one to open first.

Time passed and soon it was winter. In view of the heavy snowfall, troops on both sides of the LoC would keep a low profile. But I ensured that we never lowered our guard. In those days we had first-generation black-and-white televisions with the screens no bigger than today’s laptops. We unfortunately couldn’t receive the transmission of Doordarshan. Instead, we saw the Pakistani TV programmes. Their news bulletins were mere propaganda – India-bashing. But their plays were good and some English serials like Star Trek were absorbing. However, we did send a larger number of soldiers on leave during the winter. As the journey in transit from the rail head at Jammu to Tangdhar usually took over a week in the winter, the men were encouraged to avail of four months’ leave at a time, for the current year and the following year as well, and thereby save time in movement.

I vividly recall my first experience of heavy snowfall at my piquet. I had gone to visit one of my forward posts, situated deep in the gorge but on our side of the Kishenganga river. It was a classic case of eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation separated by a 100-odd metres with the river in between. Each side could watch the activities of the other. A visit by the company commander was an important event and the Pakistanis were keenly watching the happenings. I always insisted on having a ‘Sainik Sammelan’, an address to the soldiers, followed by a regimental song and battle cry, and a community lunch during such trips. This raised the morale and level of motivation of all ranks and helped me to create esprit de corps among my team. This became my leadership style. It was a gruelling one-and-a-half hour climb back to my company HQ and there was already some snow in places on the track. Besides, it started snowing as we reached the half-way point. The final ascent to the top was very steep as usual. I was quite fatigued by the time I finally reached my bunker. A hot bath and a large peg of rum along with the usual snacks relaxed me.

The next morning I was greeted by a thick carpet of three-to-four-feet of virgin snow all around. It was a complete ‘whiteout’, something I hadn’t witnessed before. The purity of the white colour of the snow is beyond comparison. The deodar branches were drooping with the weight of lumps of soft snow, many having collapsed and fallen to the ground, unable to bear the weight. With a thud, a huge white ball would suddenly fall off these trees and strike the earth, as I walked around the post. It was the most fascinating and beautiful sight I had ever seen.

In the summer of 1979, Rohini and the children came on a month’s vacation in Tangdhar. Lieutenant Colonel Dhillon told me that I could spend time with my wife and kids, but would have to be back in my piquet at night. So, it was a lot of trekking for me those days. Coming down to the Battalion HQ, I used to literally jog and reach in 45 minutes or so. Going back was tough. Rohini felt bad for me, but it was better than being far away in Jalandhar. At least we could meet and snatch some moments together. Besides, it was much cooler in Tangdhar as compared to the hot summer in the plains of Punjab. When their holidays were about to finish, I took leave for a week and we travelled to Jalandhar. On the way we spent two days at Gulmarg with 2 Maratha LI being commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Har Ranjit Kalkat. We were welcomed very warmly and our stay with the Kali Panchwin (the Black Fifth, as this battalion is traditionally known) was memorable. In those days, Kashmir was peaceful and the people were friendly.

The tenure of the battalion got over by mid-1979 and we got orders to move to Poona. I was happy because we were going to a good peace station where we could be together once again. It had good schools where our children could study. I was approved to become a lieutenant colonel in 1980 and by then had become the second-in-command of the battalion. Normally, I should have been made the commanding officer of 7 Maratha LI itself, but the colonel of the regiment, Major General Bachittar Singh, was requested by all ranks of 9 Maratha LI that I must be reverted back to be their CO. It was conveyed to him that there were some problems in the unit, and it would be in the best interests of the battalion if I took over the command from Lieutenant Colonel A.F. Fernandes. So once again I had to move to an operational area, this time to Tezu, a remote place in Arunachal Pradesh.

Life had been tough for Rohini and the children, who were growing up in the absence of their father. From 1973 to ‘81, within a span of eight years, I had had eight postings alternating between peace and field.3 One must admit that it was some ‘yo-yoing’! There was great turbulence and insecurity in our family life which seriously affected the education of my children, Vivek and Urvashi. Things had got so bad that if ever they saw Rohini and me packing our bags for the weekend or a holiday, they would ask, ‘Papa, are we transferred again?’ This has been the true facet of life in the infantry. We are proud of the fact that we took all this in our stride. I never represented against any of these postings.

1 Ghazala Wahab, Force, March 2005.

2 J.N. Dixit, Across Borders: Fifty Years of India’s Foreign Policy, Picus Books, 1998, p. 106.

3 Field is a short form of describing an operational or field-area deployment along the border or in counterinsurgency areas like J&K, where the families are generally not permitted.