1203

In 1203 King John was the ruler of a vast international empire. Besides being king of England he was master of much of south Wales and lord of Ireland. He was also duke of Normandy, count of Anjou and duke of Aquitaine, meaning that he ruled all of what we would now regard as western France, from the English Channel to the Pyrenees. From north to south his authority extended 1,000 miles, and half that distance from east to west. Travellers could pass from the border of Scotland to the border of Spain without ever leaving his territories. Millions of people, speaking at least half a dozen different languages, were his subjects. By any measure, his was the most important and powerful dominion in Europe.1

But in the spring of 1203 it was a dominion under attack. John had a rival in the shape of the king of France, Philip II – or Philip Augustus, as he had been dubbed by an admiring contemporary chronicler. At thirty-seven Philip was just one year older than John, but he had been a king for much longer – twenty-three years to John’s four. The kingdom he ruled was much smaller than the France of today, but since the start of his reign Philip had been consolidating and extending his power. He had, for example, completely transformed his capital at Paris, giving it new walls, paved streets and a palatial royal castle called the Louvre, expanding the city so that it was many times larger than it had been before. He had long nurtured similar plans to expand the size of his kingdom, and in 1203 he put them into action.2

Philip began his assault on John’s empire a week after Easter, sailing down the River Loire into the heart of Anjou and seizing the castle at Saumur. At the same moment his allies in the region – John’s rebellious subjects – successfully besieged several other castles and occupied the city of Le Mans. In this way John’s enemies cut his empire in two, separating Normandy from the provinces further south. Normandy was Philip’s main target, and he immediately moved his forces against it, quickly taking a string of major fortresses along its eastern frontier, some of which surrendered to him without a struggle.3

John himself was in Normandy at this time, moving between the castles on the frontier and the duchy’s principal city, Rouen. According to one chronicler, messengers came to him with news of the invasion, saying ‘the king of France has entered your lands as an enemy, has taken such-and-such castles, carried off their keepers ignominiously bound to their horses’ tails, and disposes of your property at will, without anyone resisting him’. John’s reaction, however, was reportedly one of blithe indifference. ‘Let him do so,’ he replied. ‘Whatever he now seizes I will one day recover.’4

This is almost certainly inaccurate and unfair. The chronicler who reports these words, Roger of Wendover, was one of the king’s harshest critics. He was a contemporary, in that he lived through John’s reign, but he did not write his chronicle until after the reign was over. His account is extremely valuable, sometimes providing credible information that cannot be found elsewhere. But it also contains stories that are demonstrably false, and is shot through with hindsight and moral judgement. Describing John’s behaviour at the time of Philip’s attack, for instance, Wendover accuses him of ‘incorrigible idleness’, claiming that he feasted sumptuously every day and enjoyed a long lie-in every morning.5

In fact we can see from John’s itinerary that during these weeks he was constantly on the move, and other sources state that his first reaction was to try to negotiate, offering the French king any sum of money to break off his attack. When this failed, he pinned his hopes on the intervention of the pope, who wrote to Philip in May, exhorting him to desist or face the Church’s condemnation.6 Then, in the middle of July, John tried to seize the military initiative. He succeeded in recovering a castle in central Normandy, Montfort-sur-Risle, whose lord had defected at the start of the crisis, and the following month he came close to retaking two other castles, Alençon and Brezolles, on the duchy’s southern border, but in both cases he retreated on being told that a French army was approaching. Philip meanwhile convened a council of his own bishops and barons who collectively told the pope to mind his own business. Towards the end of August he resumed his offensive, marching his army down the River Seine to begin his assault on the greatest of all John’s defences.7

Today Château Gaillard is a badly scarred ruin, set high on a rock above a bend in the Seine, about twenty miles south-east of Rouen. In 1203 it was a brand-new building, with pristine stonework and regal interiors, the most technologically up-to-date fortress in Europe. It had been constructed just a few years earlier by John’s older brother, and immediate predecessor, Richard the Lionheart. Richard had waged a long and inconclusive war against Philip Augustus along the Norman–French border, and Château Gaillard – literally, ‘the Saucy Castle’ – had been created as both a defence for Rouen and a forward base for future conquests. It was built at lightning speed between 1196 and 1198, and at the gargantuan cost of £12,000. (The mighty Dover Castle, built a decade earlier, had cost only half as much.) Richard’s new fortress was nonetheless perfectly realized and, in his own immodest opinion, invincible. According to one contemporary, the king had boasted that he could hold it even if its walls were made out of butter.8

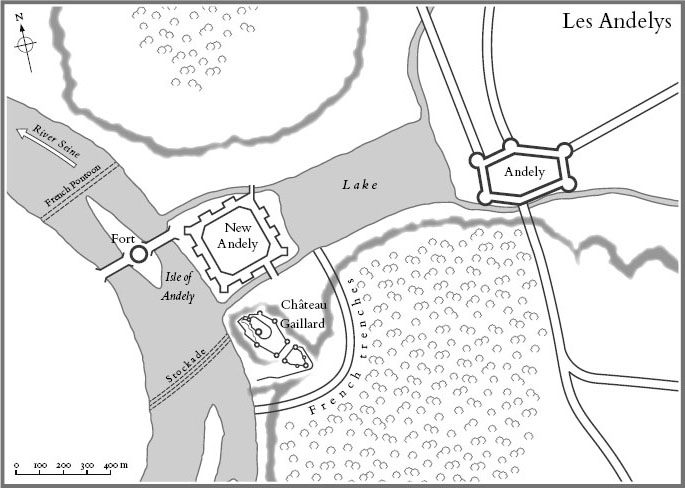

Philip was finally ready to put the Lionheart’s bold claim to the test. Before he could assault Château Gaillard itself, however, he had to contend with the elaborate series of outer defences that Richard had constructed in the castle’s shadow. At the foot of the rock, on a marsh formed by two small tributaries of the Seine, was a new fortified town. It was about a mile to the west of an existing settlement called Andely, and so became known as New Andely (or Little Andely). Opposite this new town, in the middle of the Seine itself, was a long, narrow island – the so-called Isle of Andely. Here Richard had created a crossing of the whole river by building bridges to the shore on either side, and to protect it he had given the island a fortress of its own: an octagonal tower, ringed with a double set of wooden palisades.9

Philip’s first challenge was therefore to isolate Château Gaillard by taking these outer defences. The way in which he did so is described in great detail by his chaplain, William the Breton, who was an eyewitness.10 Seeking to avoid the castle itself, the French king led his army up the left bank of the Seine, intending first to tackle the fortress on the Isle of Andely. The garrison there, hearing of his approach, had destroyed the bridge that linked the island to the left bank. But Philip had clearly anticipated such a move, for on their arrival his troops immediately set about creating a replacement crossing, requisitioning boats and barges to transport the necessary building materials into position. This itself was a perilous undertaking, because a little upstream from the island, directly under the walls of Château Gaillard, King Richard had planted a wooden stockade across the river, prohibiting all traffic beyond that point. To get his bridge-building supplies through this barrier, Philip had to send a team of swimmers out into the Seine, armed with axes, and have them hack out a breach. Contending with both the strong current and a shower of missiles from the castle above, these men sustained heavy casualties, but at length an opening was created wide enough for boats to pass. The rest of Philip’s men began to construct an elaborate pontoon bridge, sufficiently strong and massive to bear the weight of his army, and fortified with two large towers. It was built not to the island, but right across the Seine to the opposite shore. As soon as it was completed, the king led the bulk of his forces across to form a new camp on the river’s eastern bank, directly menacing the new town of Andely, and leaving the garrison of the island cut off from both sides.

News of the attack on Andely had by now reached the ears of King John, who responded by returning to Rouen and devising a plan for the island’s relief. Two separate forces would mount a daring night-time assault. The first, consisting of knights and mercenaries, would proceed along the left bank of the Seine and tackle the French soldiers who remained on that side of the river. The second would be a maritime force: a fleet of galleys, built by Richard to patrol and defend the Seine, together with other ships captained by pirates, would smash through the French pontoon, bringing supplies to the besieged garrison on the island.

The plan was put into immediate effect. The land army was not led by John, who remained in Rouen, but by William Marshal (or ‘the Marshal’, as contemporaries called him), a military veteran in his mid-fifties, who had plenty of experience executing such devious operations. Advancing along the left bank as agreed, his army fell upon the sleeping French camp in the pre-dawn darkness. Since most of those sleeping there were apparently merchants and other hangers-on rather than soldiers, it was an easy victory, with over 200 said to have been killed. Others tried to escape across the pontoon bridge in such numbers that it broke under the strain. The fleet, it seemed, would have no difficulty in completing the bridge’s destruction.

Except that the fleet was nowhere to be seen. While the Marshal and his men had made their way along the river unopposed, the naval force had run into unexpected difficulties – John’s scheme had failed to take into account the strength of the tide his oarsmen would have to contend with. In the meantime, the French who were camped on the opposite side of the river had been woken by the noise of the assault and the panicked arrival of their fugitive countrymen. Under the direction of William des Barres, a commander with no less experience than William Marshal, the rout was arrested. Hasty repairs were carried out to the bridge by torchlight, and, as soon as it was passable, des Barres led the French back across to confront their enemies. Surprised at this unexpected reversal, the Marshal’s men were now defeated in their turn, with many killed or taken prisoner. The Marshal himself escaped.

The French, thinking the assault was over, recrossed the river, either to celebrate their victory or return to their beds. But a short while later the cry to arms again rang out around their camp: the mercenary fleet had been sighted. The fleet, if not quite so large as William the Breton would have us believe, was clearly a formidable fighting force; there can be little doubt that, had it arrived as planned – in tandem with the Marshal’s army and under cover of darkness – the French lines would have been broken and the Isle of Andely resupplied. But, delayed as they were, the naval forces were deprived of the element of surprise, for by this point the sun was rising. By the time they reached the pontoon bridge, both banks of the river and the bridge itself were lined with French soldiers, and the ships sailed into a blizzard of arrows, stones and crossbow bolts. Some of them did crash into the pontoon, and their crews began desperately hacking at its timbers and cables. But the defenders engaged them in savage hand-to-hand combat, and the river ran red with blood. When two of the ships at the front of the fleet were sunk by a giant falling timber, the remainder retreated in confusion, back in the direction of Rouen. Two more ships were captured by the French as they fled.

Having beaten off their assailants, the French made an immediate attempt to take the island. According to William the Breton, this was achieved by a heroic individual who swam out to an undefended spot on its eastern side and threw firebombs at the wooden palisades surrounding the fortress. Very quickly the whole complex was engulfed in flames. Those members of the garrison who had taken refuge in the cellars of the tower perished; those who escaped were forced to surrender to their attackers. Seeing that the island had fallen, the citizens of New Andely abandoned the town and fled up the hill to seek refuge in Château Gaillard. Philip occupied the deserted town and settled down to besiege his main target.

With the French in total control of both the Seine and the surrounding countryside, there was no question of attempting another relief operation. Instead John tried to lure Philip away by launching an assault on his allies. In early September he left Rouen with the remainder of his forces, heading in the direction of Brittany. The Bretons had been in rebellion against him since the previous autumn, and John now exacted his revenge, invading the duchy and laying it to waste. His mercenaries destroyed the city of Dol, burning down the cathedral and carrying off its relics.11

Philip, however, refused to be distracted. While John was busy harrying the Bretons, the French king’s engineers were tightening their grip on Château Gaillard. Huge ditches were dug all the way round the castle on its landward side to prevent relief or escape. Along their length wooden forts were erected at regular intervals – seven in total, each surrounded by a ditch of its own, and filled with as many soldiers as it could hold. Philip himself, meanwhile, had left to attend to the siege of another of John’s castles, Radepont, which he succeeded in taking in mid-September. Radepont lies just fifteen miles from Rouen.12

In early October, therefore, when John returned to his capital, it was to scenes of increasing chaos and despair. The city was said to be in flames at the time of his arrival (presumably due to an accident rather than enemy action) and the fire came close to destroying the ducal castle. This detail is provided by The History of William Marshal, a long biography of the famous warrior written in the 1220s, not long after his death. The History is one of our most valuable sources for John’s reign but, like the chronicle of Roger of Wendover, it has to be used with caution. It was commissioned by the Marshal’s family to defend his reputation, and at every turn seeks to disassociate him from King John. In its account of 1203, for example, it makes no mention at all of the Marshal’s failed mission to relieve the Isle of Andely. It does, however, convey in vivid terms the growing desperateness of the situation in which the Marshal and his master found themselves that autumn.13

‘Sire, listen to what I have to say,’ says the Marshal after their return to Rouen. ‘You haven’t many friends.’ The military situation, he explained, was becoming hopeless.

‘Let any man who is afraid take flight!’ replied the king. ‘For I shall not flee this year.’

‘I am well aware of that,’ said the Marshal. ‘I have not the slightest doubt about it. But you, sire, who are wise and powerful and of high birth, a man meant to govern us all, paid no attention to the first signs of discontent, and it would have been better for us all if you had.’14

This frank exchange made John predictably angry, and he shut himself away in his chamber. The next day he was nowhere to be found in the castle, and his men were annoyed to discover that he had slipped out of Rouen without them; they eventually caught up with him on the coast at Bonneville-sur-Touques, more than fifty miles away. For the rest of October, the king made similar rapid journeys around central and western Normandy, shoring up his remaining defences and doubtless trying to rally more support. But everywhere he went he was now dogged by fears of treachery. Returning to Rouen in November, he travelled by a deliberately indirect route; the main roads, he thought, were being watched by ‘men who had no love for him’.15

Back in Rouen, John explained to his Norman followers that there was now only one solution: he must go to England, and persuade the barons there to come to Normandy’s aid. Assuring his audience that this trip would be brief, he secretly sent his baggage on ahead to Bonneville. His own departure was equally furtive, for had become convinced that there was a plot among the Norman barons to hand him over to the king of France. With just a handful of trusted intimates, including William Marshal, John stole away from the city before daybreak. Travelling west by a circuitous route, he ultimately arrived at Barfleur, a port on the Cherbourg Peninsula, where a fleet to ferry him and his household across the Channel was waiting. The king sailed on 5 December. Most people, says the Marshal’s biographer, suspected he would never return.16