7

THE HAND

Hands are the most complex part of the body with regard to the way they function. They are equally challenging to sculpt. As with other parts of the body, everyone is first drawn to the details—in this case, the creases of the knuckles and the veins on top of the hand. I’ve heard of a few students who were so intimidated by the hands that they sculpted gloves over them and renamed the piece just to avoid modeling hands. Don’t even go there!

STEP-BY-STEP CONSTRUCTION

When starting the hand, as with the figure, begin with simple shapes that best represent the form, and that will act as the foundation or stage one in the sculpting process. Then we’ll move on to stages two and three, developing the form and finishing.

This giant, ancient, marble carving of a hand in a pointing gesture is displayed in a courtyard museum in the Piazza del Campidoglio in the heart of Rome. Note the block shape of the fingers. Each section of the fingers has top, bottom, and side planes. The third, fourth, and fifth fingers curl and touch the palm below the thumb. The fingertips of those fingers are on a 45-degree angle, from the third finger near the thumb to the little finger near the base of the palm. Fingernails curve on the elliptical shape at the end of the fingers. The thumb is on the side of the hand.

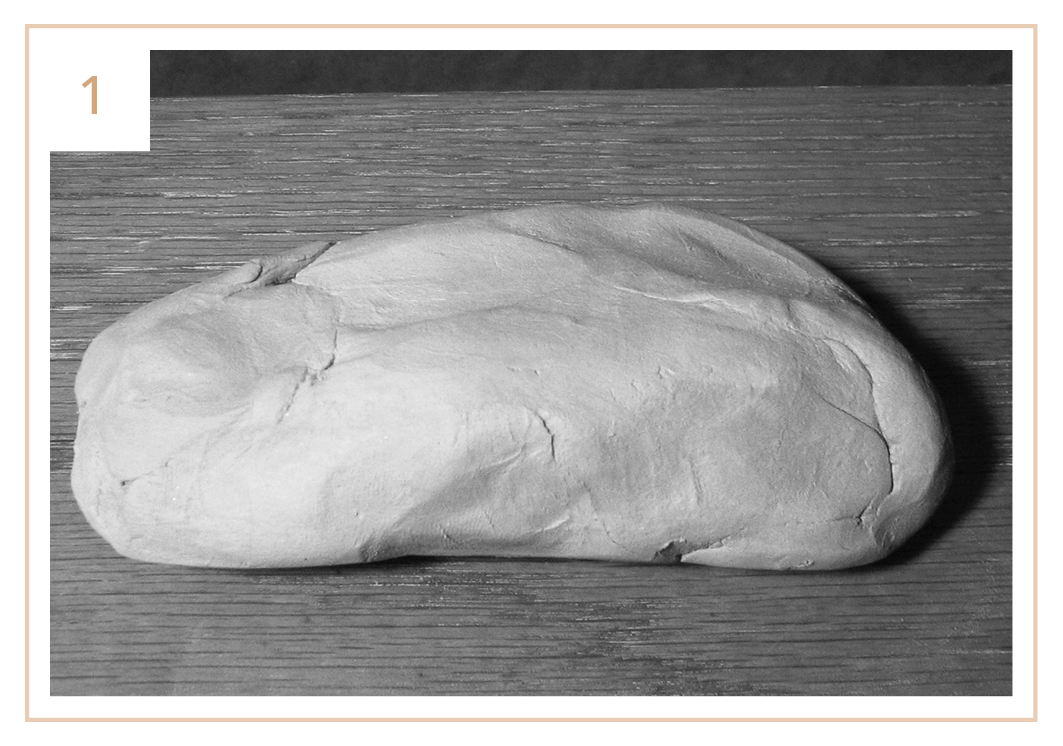

1. Roll a coil of clay, drop it on a laminate board, and stretch it into a rectangular block shape. Make the length twice the width.

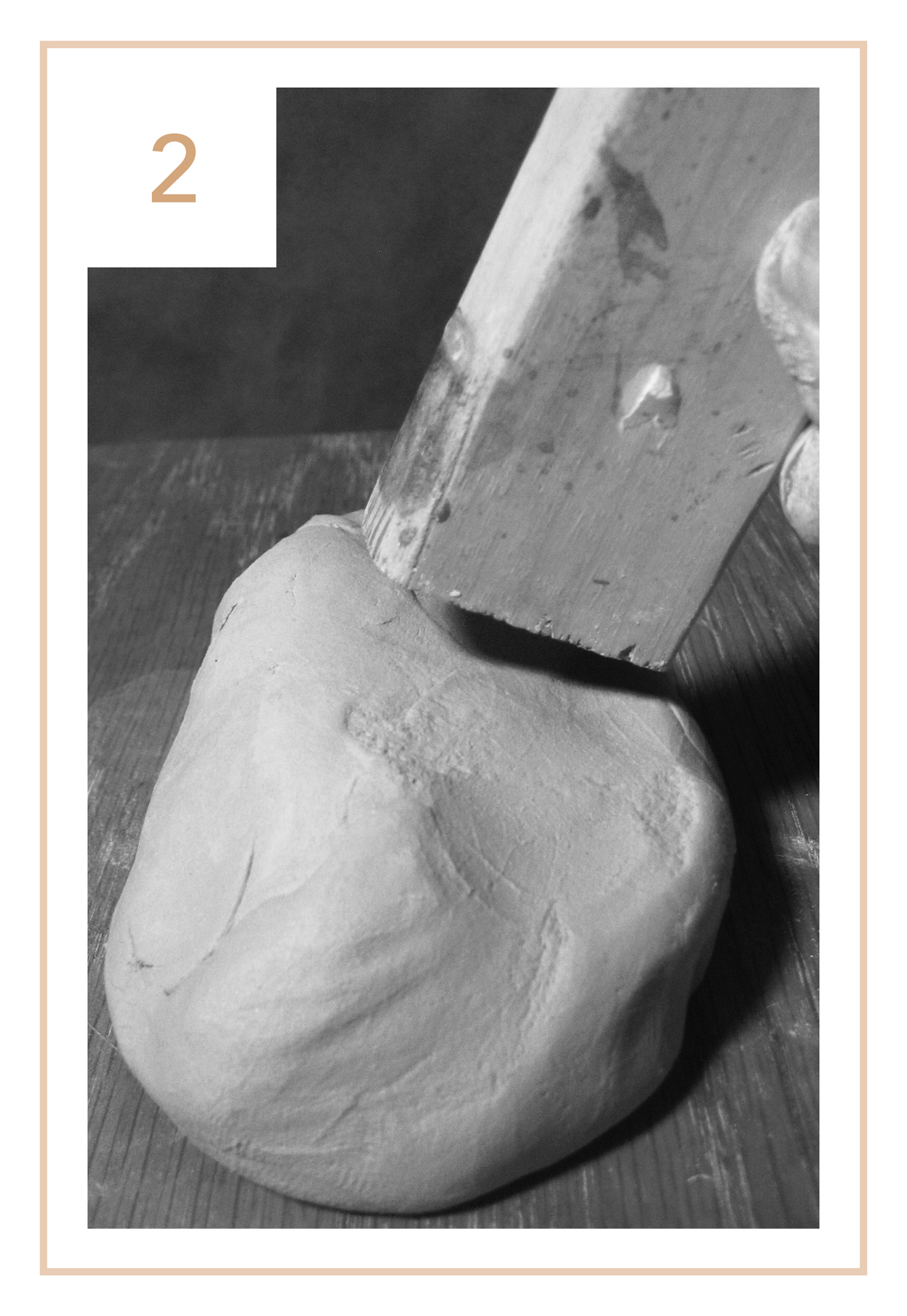

2. Using the wood block tool, tap the top surface of the clay block on a 45-degree angle, from one end to the other.

3. Taper the mass of the four fingers from the wide area of the knuckles to the fingertips. Draw guidelines for the fingers, drawing the center line first and then drawing lines in the center of each remaining half. This is a left hand with fingers, so the thumb will be added to the right side later. The wrist section of the lower arm will attach to the front plane at the end of the hand. Note the slope of the hand from right to left. Draw a curved guideline for the knuckles in the center of the top plane, across the width of the hand. Note that the index (first) fingertip is farther from the wrist than the little finger (pinkie). Start the guideline at the knuckle of the index finger and curve it back to the knuckle of the little finger. The width of the hand is wider across the knuckles than at the fingertips when the hand is opened and the fingers are touching one another. The index and pinkie fingers curve in toward the middle finger.

4. Cut the top plane of the hand with the wood stick to lower the hand at the wrist area. Start the cut at the knuckles, and then slice toward the wrist, keeping the angle sloped from the index finger to pinkie. Do the same from the knuckles to the fingertips. The hand is wedge shaped. The knuckle of the index finger is the high point of the hand; the wrist and fingertips are the low points.

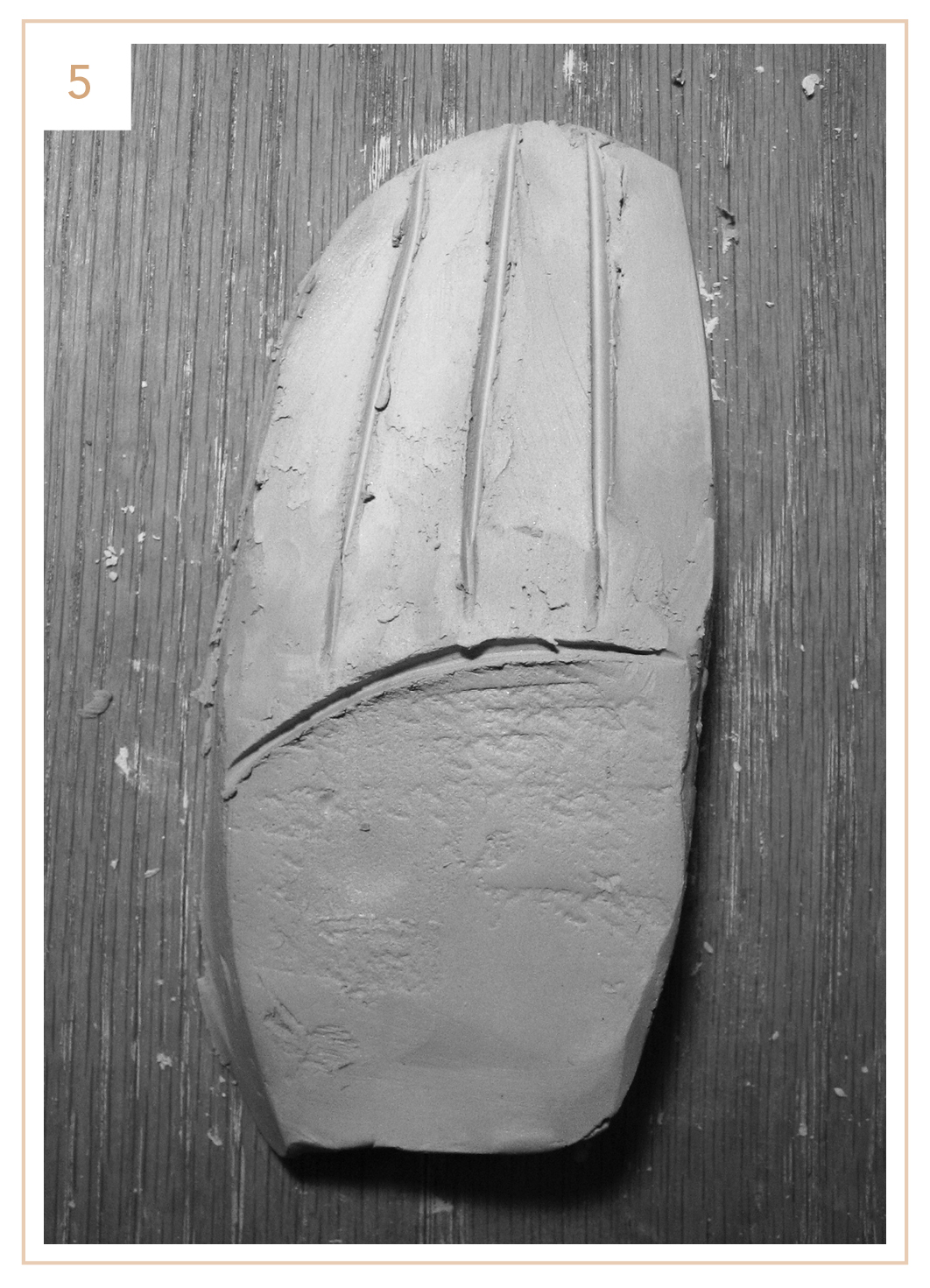

5. The view of the hand from above shows the curved line for the knuckles. The fingers taper to the tips, and the hand is wider across the knuckles than at the fingertips. The hand also tapers from the knuckle to the wrist. The fingers are different lengths and create a curved contour along the tips. Cut and shape the curve in the clay for the ends of the fingers. The curve should be parallel to the curved line of the knuckles. The final foundation shape of the hand should look like a hand wearing a mitten or sock.

6. Check the front view of the fingertip end. The knuckle of the index finger should be higher than the knuckle of the pinkie. The plane of the tops of the fingers slopes down and forward from the knuckles to the fingertips, and down and to the outside of the hand from the high knuckle to the low one.

7 & 8. On the top plane, draw two curved guidelines lines for the second and third sets of knuckles across all the fingers (7). On all fingers except the first, create planes on each tier of knuckles, creating a slight step down from knuckle to knuckle from top to bottom (8). Leave the index finger as is for now.

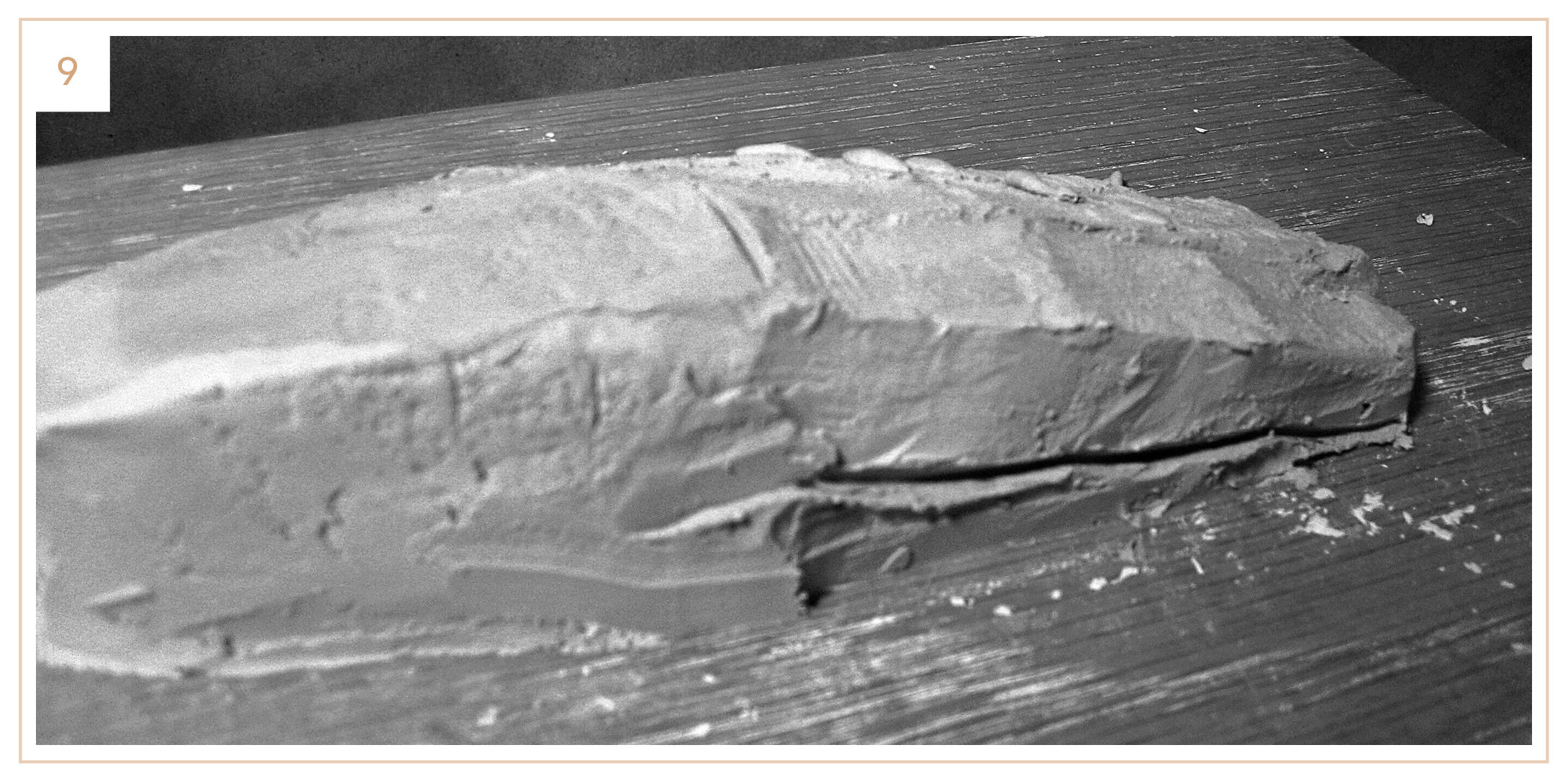

9. On the side of the hand where the thumb will be attached, draw a guideline along the underside of the index finger. Clay below this line will be removed to thin out the finger. Make three planes on the index finger, and begin forming the knuckles.

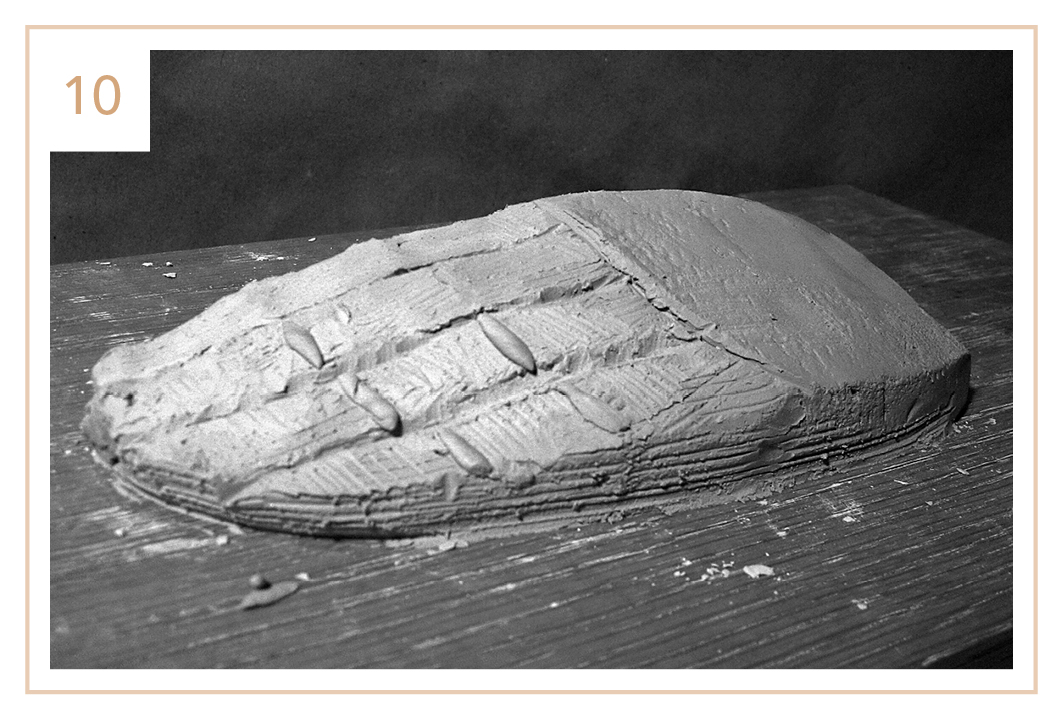

10. Add small strips of clay to each knuckle and begin shaping the fingers. Put the edge of the riffler in between the fingers, roll the tool, and press on the sides of the fingers. The sections of the fingers should be narrower than the knuckles.

11. Cut the fingers to their proper relative lengths, giving a rounded shape to the tips: The middle finger is the longest, ring finger is next, the index finger follows that, and the pinkie is the shortest. Hold your hand up, and note where each fingertip ends in relation to the place on the finger next to it. For example, on my hand the pinkie ends a bit higher than the third knuckle of the finger next to it.

12. The thumb is a separate form that attaches to the side of the hand and begins at the wrist. Hold your left hand out in front of you with the top of the hand facing the ceiling. Relax your hand and notice that the thumb drops down and out to the side; it’s not part of the hand mass. The knuckles and fingernails are located on the top plane of the fingers. The parallel bottom plane has the thicker muscle pads between each knuckle. The fingers have four sides (planes), so make them slightly rectangular at first. Place a cylinder of clay at the wrist for the first phalanx, or section, of the thumb at a 45-degree angle to the index finger. Also, begin to fill the space between the thumb and hand.

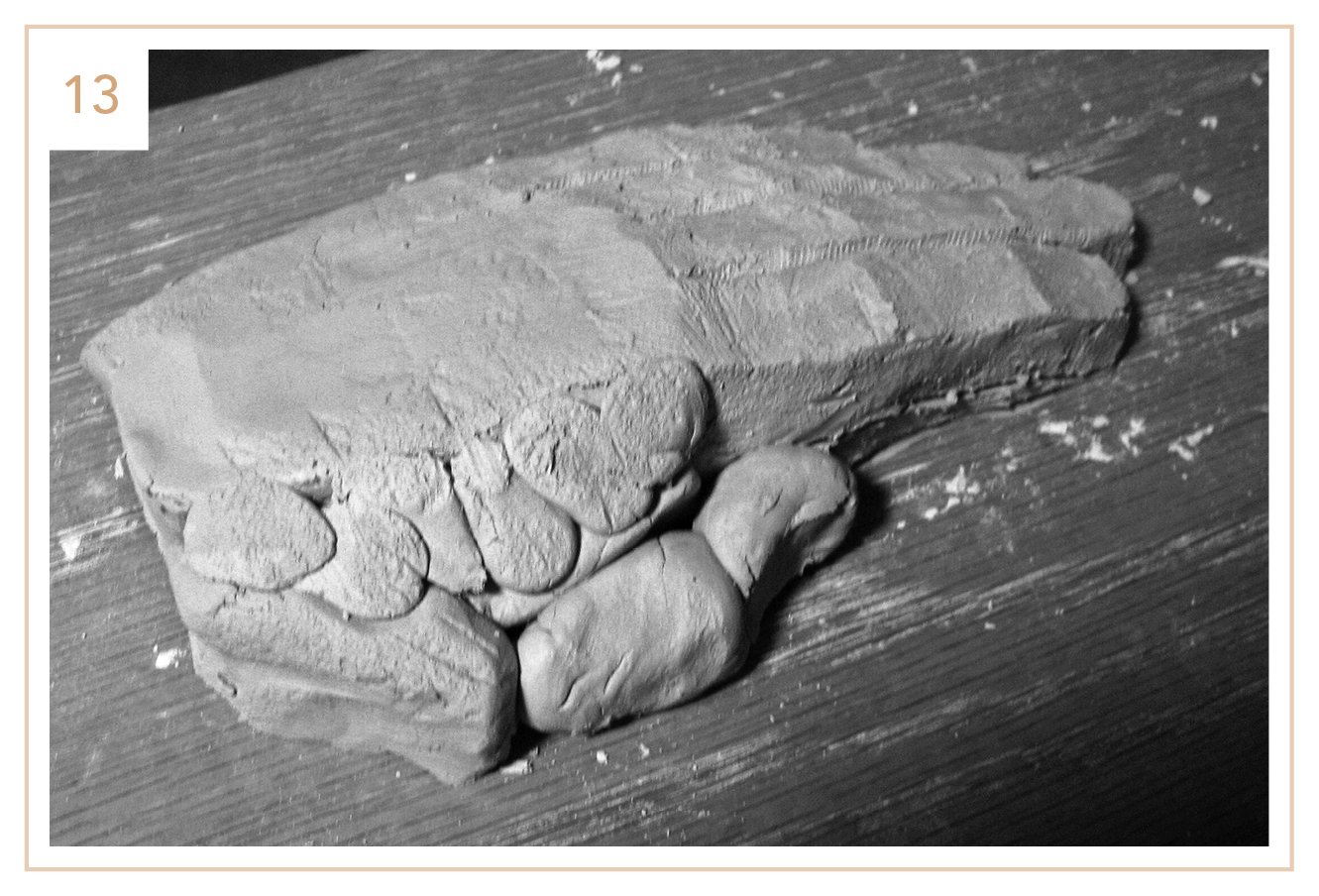

13. Add clay pieces for both the second and third phalanx of the thumb. Continue to fill the space between the top edge of the hand and the thumb with strips of clay. Tap the thumb and clay in this area to make a flat plane on the thumb and on the area between the thumb and hand.

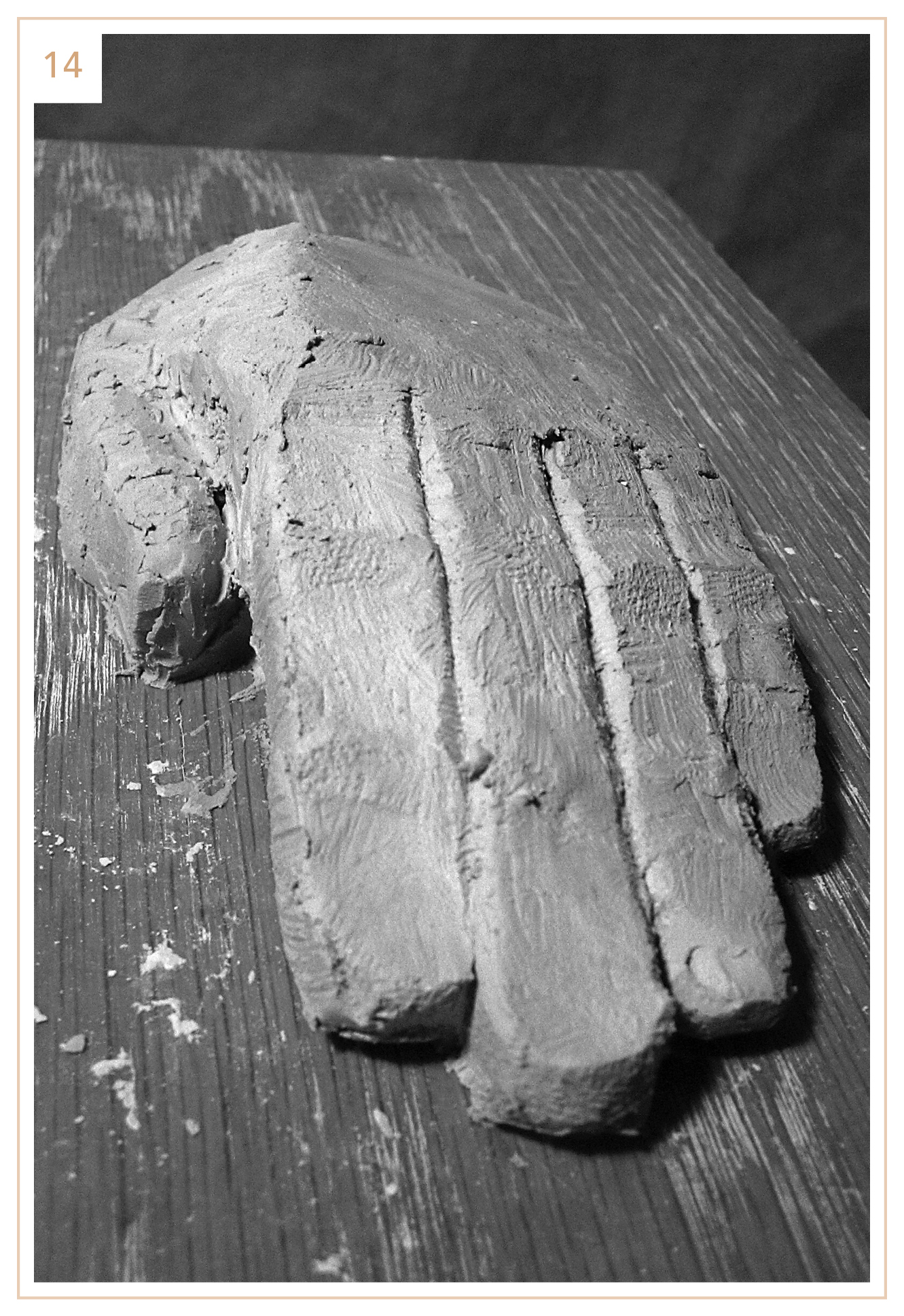

14. There’s a flat, sloping, triangular-shaped plane on the side of the hand between the thumb and index finger. This is where the small, puffy interosseous muscles are located. The top plane of the hand and this triangular side plane meet, creating a plane break along the hand between the wrist and the index finger. Smooth the clay together in this area. Note that the thumbnail plane faces to the side and the fingernail planes face upward.

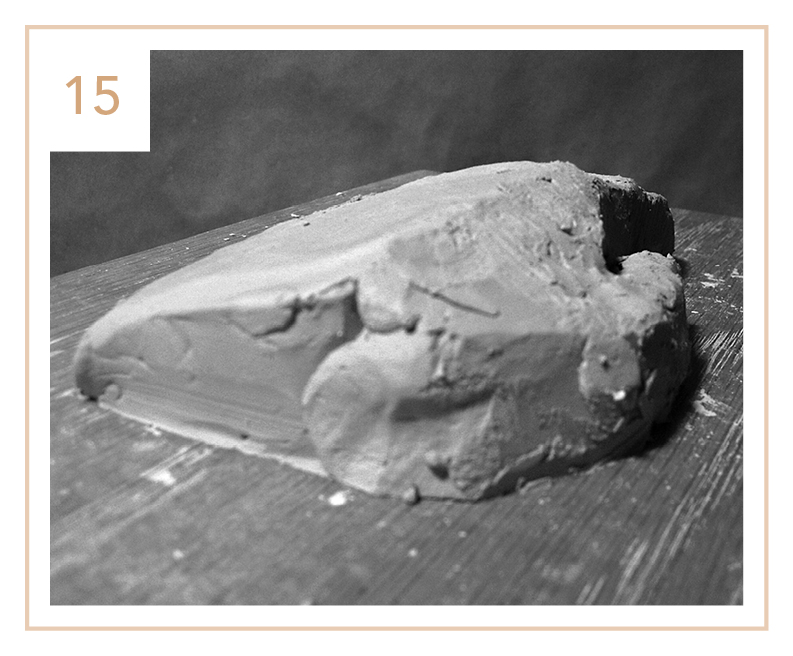

15. Use the wood block tool to tap the side plane of the thumb and triangular plane shape of the interosseous muscle area, starting at the wrist and moving toward the fingertip.

16. Lift the hand up on its wrist end. Rake the finger mass with the wire loop tool to thin it out. Rake down to the palm, where the fingers begin. Make a narrow plane on that small top edge of the palm.

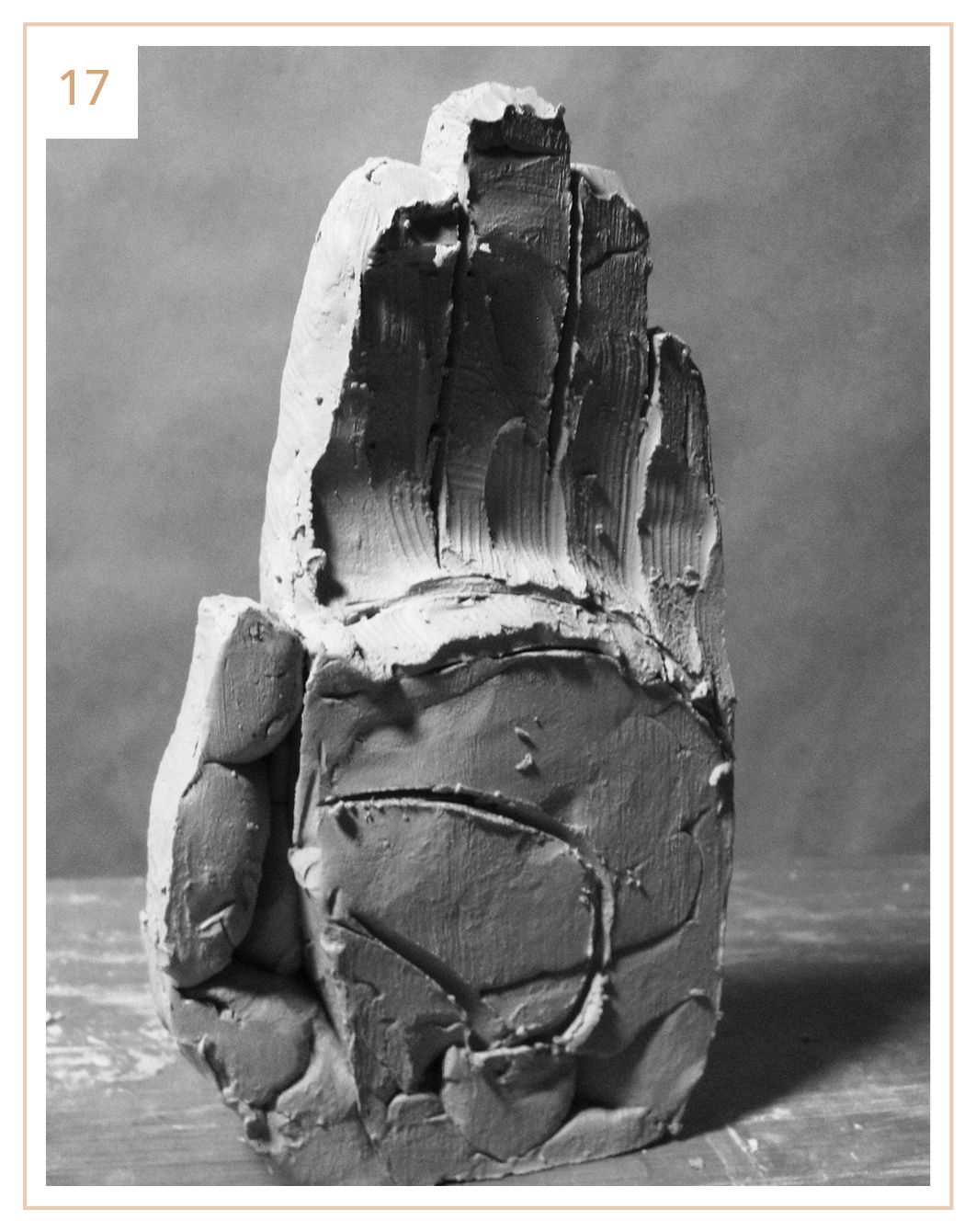

17. Draw a semicircle in the center of the palm, with its open side facing the thumb, for the pocket of the palm. The palm is padded with muscles in the center and slightly thicker ones around the perimeter. Look at your palm, and close it slowly. Watch a pocket form in the center, just like a baseball glove.

18. Gently move the thumb until it’s forward of the palm.

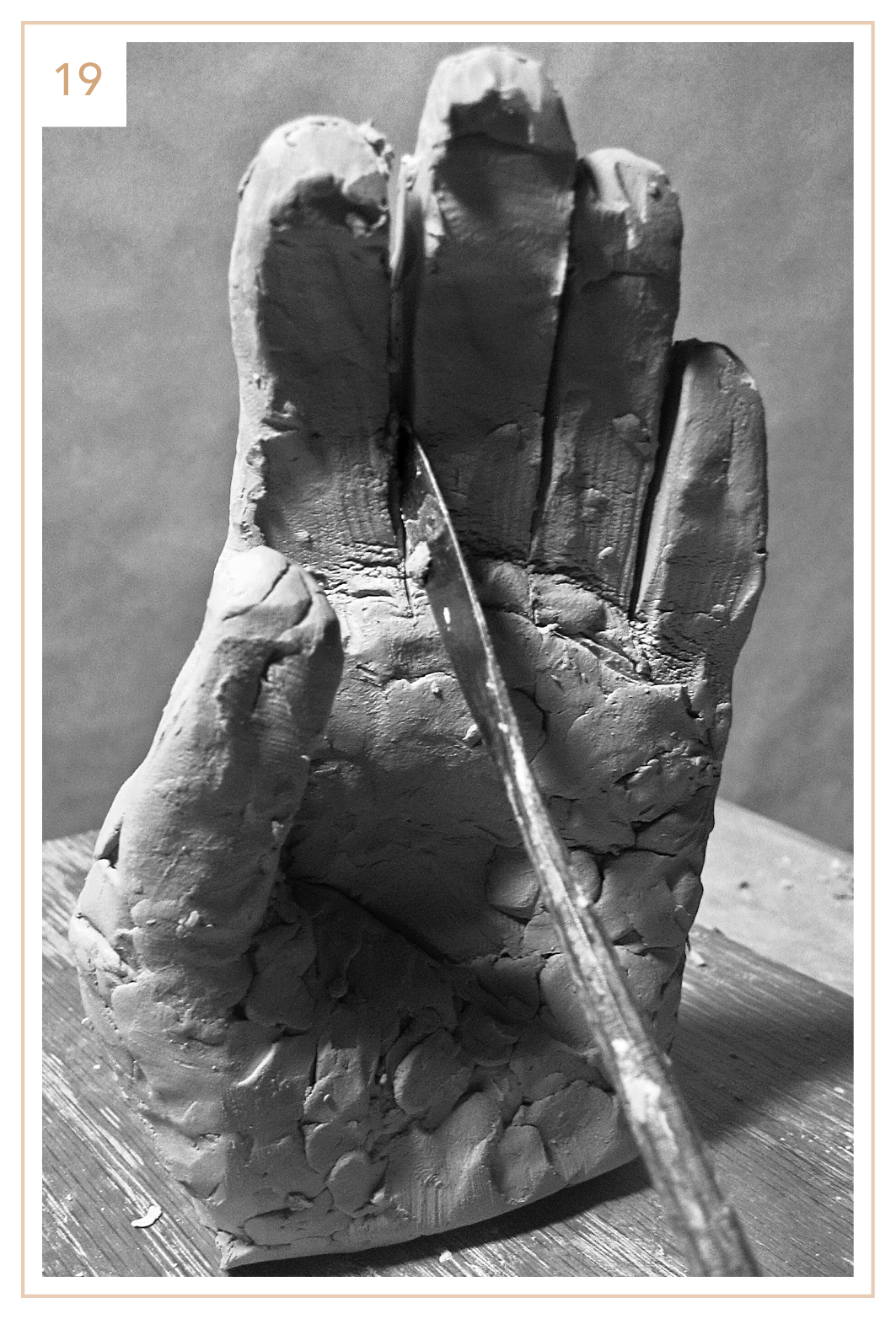

19. Cut the fingers free from one another with a plaster tool, which is a thin, metal spatula. (You can use any unserrated knife that’s handy.) Rake and thin out the center of the palm, add pieces of clay to the padded muscles around the palm, and build up the narrow plane at the top of the palm, where the fingers meet the palm.

20. Tap the clay with the wood block, and rake out the shape of the thumb, fingers, and palm. There’s no need to refine the palm, because the hand will ultimately rest palm down on the base.

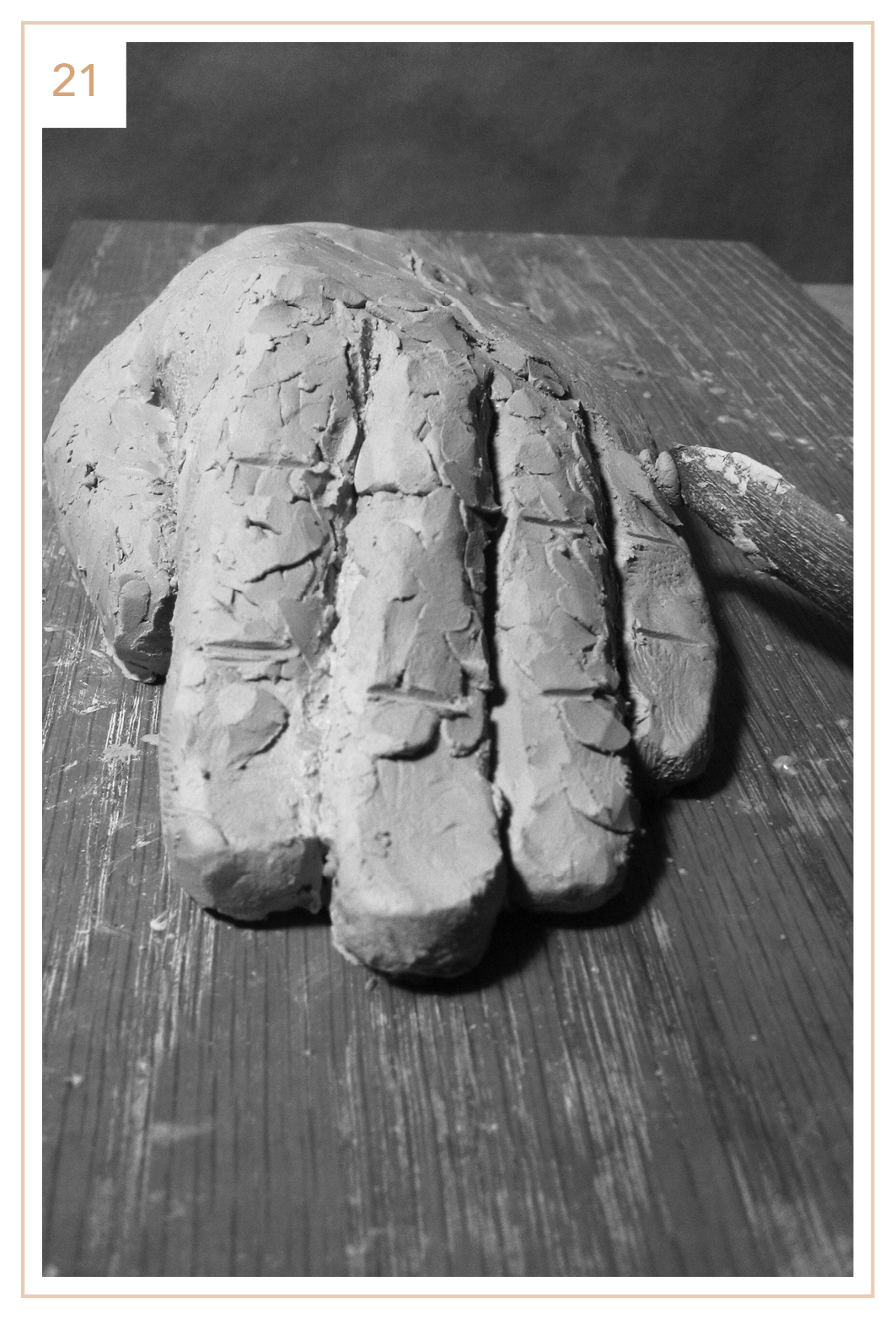

21. At this point, you can return the hand to its original orientation. For reference, stick your left hand out in front of you, palm facing the floor; relax your thumb, and let it drop. Now, rest your hand on the table, keeping it relaxed. This is the position of the hand we’re sculpting. One at a time, add small pieces of clay to the tip of the wood stick tool, and apply them to the top planes of the fingers to create rounded surfaces. Slightly round out the top surface of the thumb, where the nail is to be positioned.

22. Put small pieces of clay on the end of the wood stick tool, and add them to the knuckles.

23. Mark the triangular shape of the plane located between the thumb and the back of the hand. Add clay to this plane to build volume in the interosseous muscles. Add clay to the top plane of the hand and begin to round the surface. Tap and rake.

24. Add strips of clay to the top plane of the hand for the tendons of the fingers from the knuckles to the center of the wrist. Blend the sides of the clay strips into the hand.

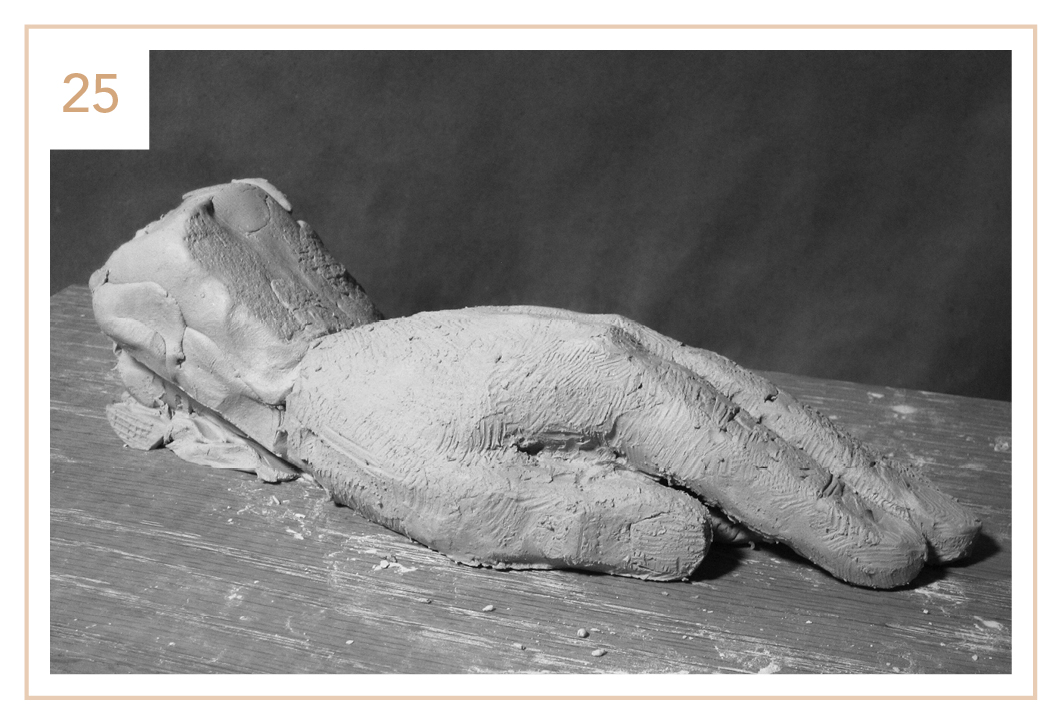

25. Attach a rectangular block of clay to the hand for the wrist. Add small pieces of clay to build up the knuckles of the thumb. Blend with the rake tool.

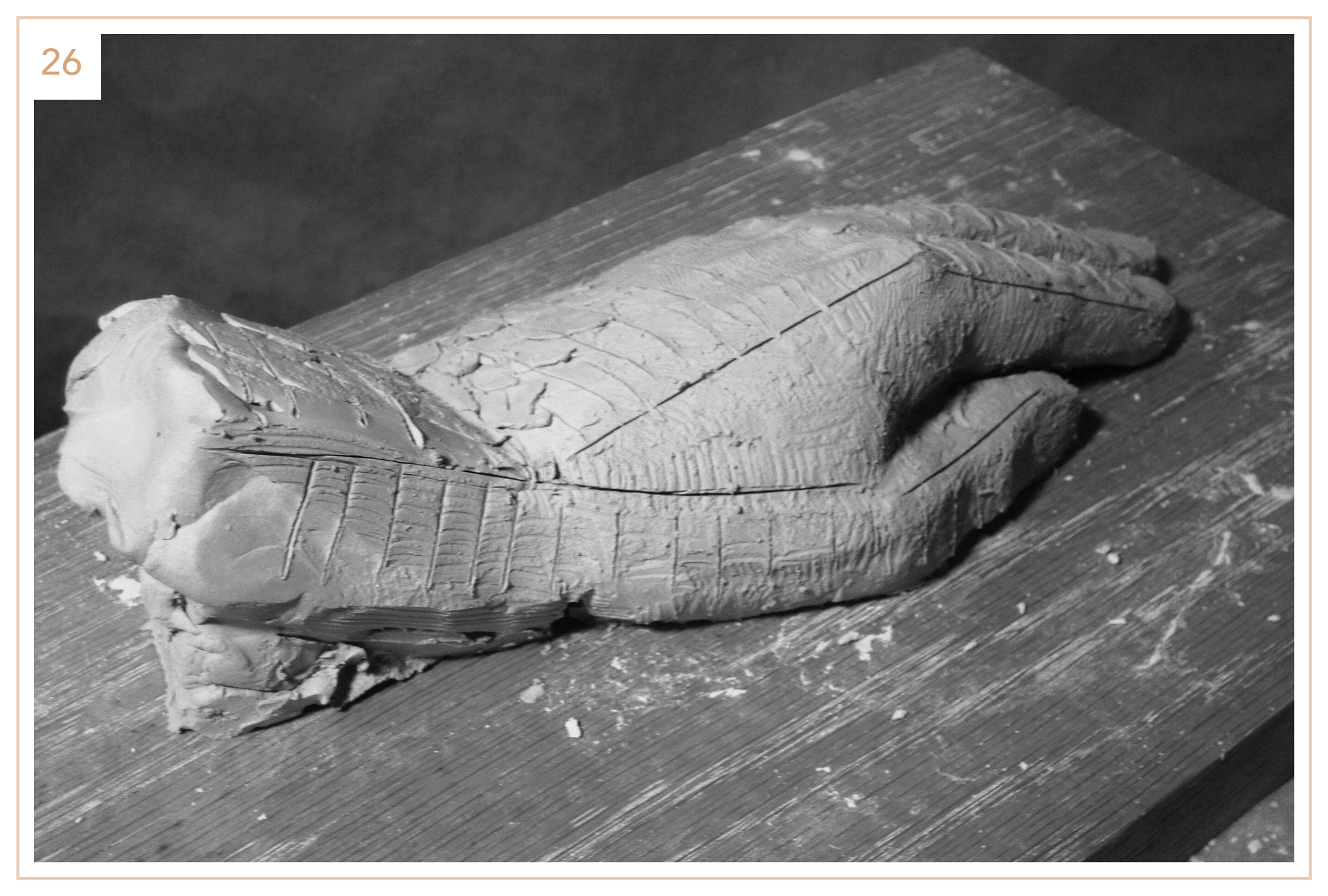

26. Tap planes on the top and side surfaces of the wrist. The top plane of the wrist is wider than the side of the wrist, and it is part of the same surface as the top of the hand and tops of the fingers. Hold your hand out in front of you, keeping your wrist and hand straight. The top plane is flat from the middle of the forearm to the fingertips. Bend your wrist back, up, and with fingers down; note that the top plane is the same, but the direction changes when bending the hand and fingers at the joints. The same is true with the narrow side plane of the wrist; it is the same plane as the side of the index finger and the top plane (the nail plane) of the thumb.

The lines drawn on the hand indicate the plane breaks, where the planes meet, between the top and side planes of the wrist and thumb, as well as the triangular plane of the interosseous muscle area.

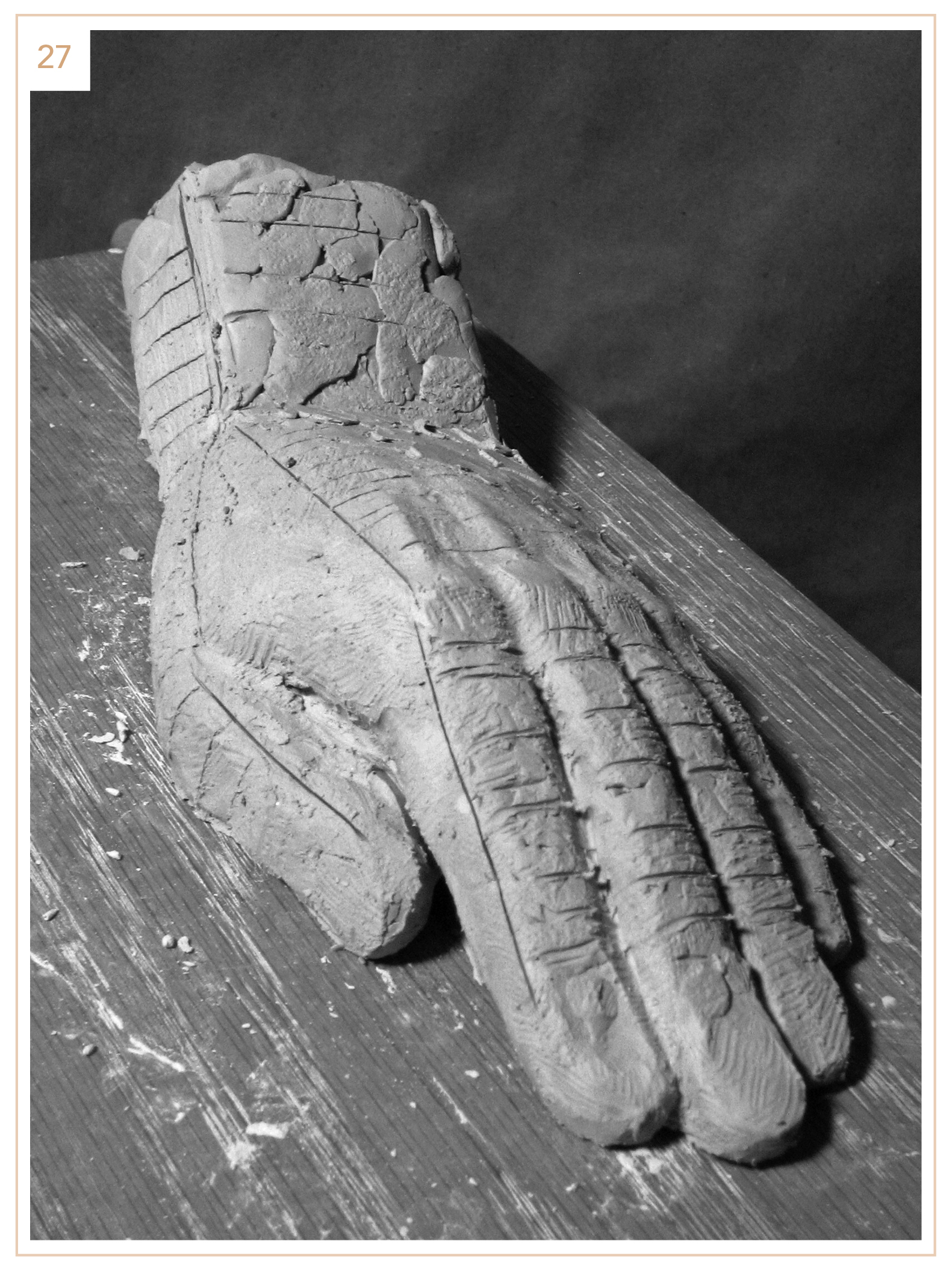

27. Curve the fingertips up at the ends. Curve the thumbnail phalanx out to the side. Shape the fingertips and knuckles, using the wire loop tool and the pressing action of the riffler to model and give shape to the forms. The guidelines here indicate the top and side plane breaks of the hands and fingers (where the planes meet).

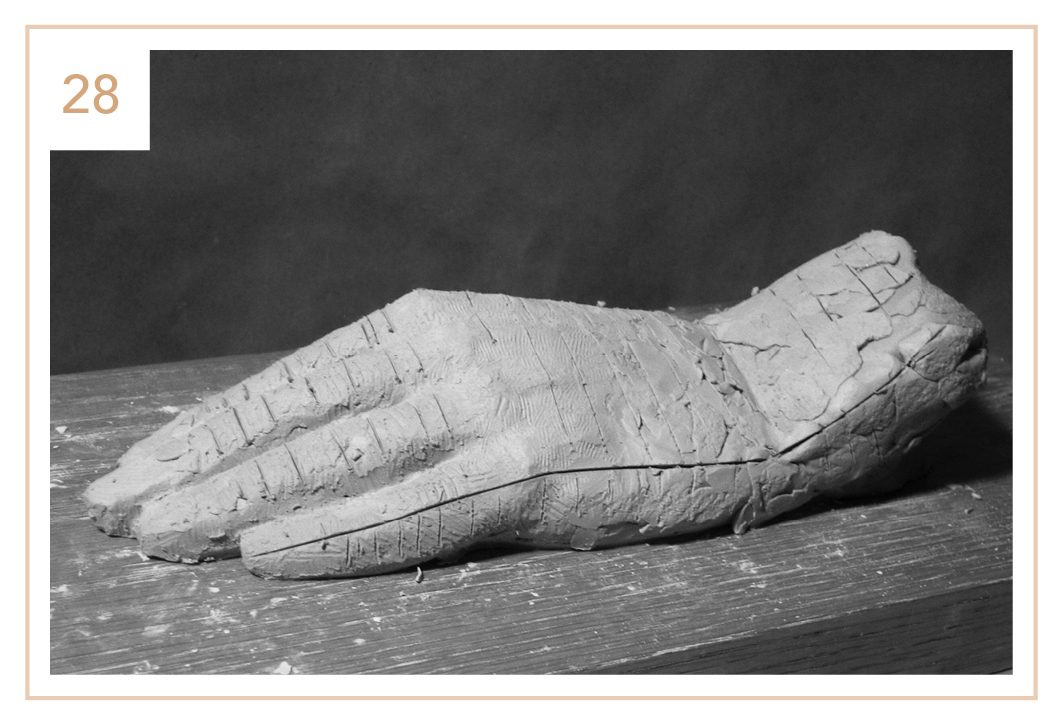

28. Add some clay to build up the thick muscle form at the outside of the hand between the pinkie and wrist (the palmaris brevis). Tap and rake the shape of the palmaris muscle, and rake the area of the pinkie under its first knuckle to give a transition between the two forms. The guideline here indicates the plane break between the top and side planes along the hand, fingers, and wrist.

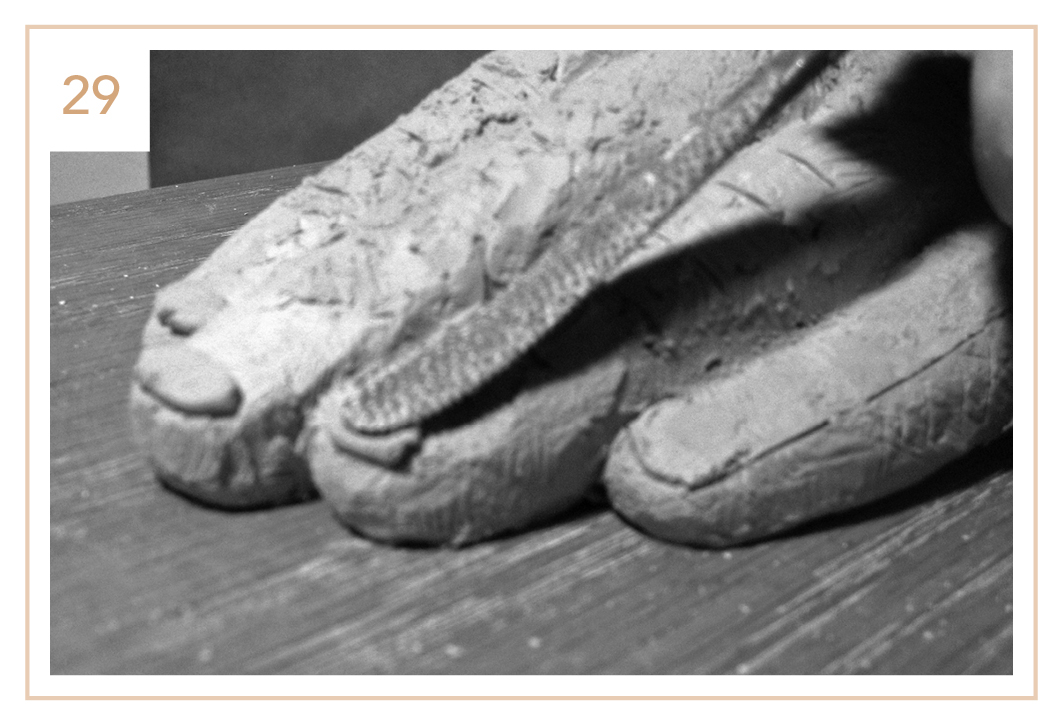

29. Add small strips of clay to the fingertips for the nails.

30. The ends of the fingers and thumb are elliptical. Round the side edges of the fingertips with a pressing motion of the riffler.

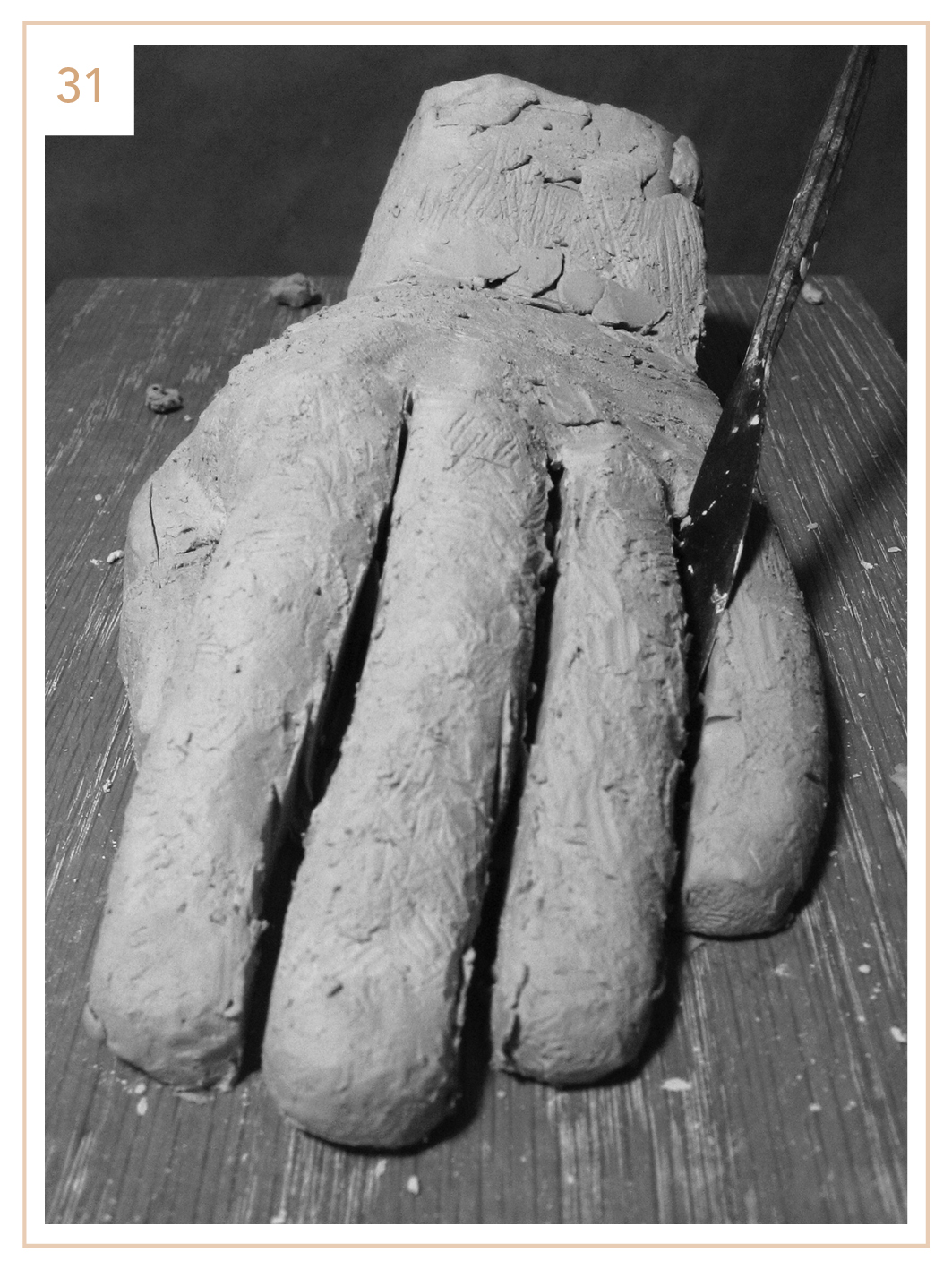

31. Use the plaster spatula tool to cut and separate the fingers at the seams. You can give individual movement to each finger when they have some separation. Bend and twist the fingers at the joints to add character. Roll each finger slightly to the outside, away from the thumb, so that the top planes of the fingers slope in the same direction as the top plane of the hand.

32. Continue to develop the knuckles and shape the tip of the thumb. The thumb is wide at the last knuckle and tapers to the tip. The last phalanx curves outward, as in a thumbs-up gesture. Round the area of the thumbnail.

33. Press the edge of the riffler into the knuckle joint of each finger to give the knuckles some depth.

34. Place the flat side of the riffler at the tip of the finger, under the nail. Press against the tip of the finger and roll the riffler from one side of the finger to the other, keeping it placed under the nail. The front edge of the nail and round tip of the finger will be shaped at the same time.

35. Rake and shape the top plane of the thumb. The sides of the thumb should be sloped where the nail is to be positioned. Create a slight bevel there with the raking action of the wire loop.

36. Blend the surface of the hand and fingers with a cross-hatching motion of the wire loop. Add more clay to build up the knuckle mass of the thumb. Rake and blend, knuckles to fingers. Vary the height of each finger.

37. Note the varied heights of the fingers and the bend at the knuckles. Also note that the fingernails are taking shape.

38. Note the downward slope across all fingers from the index finger to the pinkie. In addition, the individual fingers roll to the side in the same direction as the top plane of the hand. The fingertips roll up and rest on the center of the pads. The fingernails rest on a curved surface. Sink the fingernails into the skin at the sides and back with a pressing motion of the riffler. Note the resting position and angle of the thumb.

39. Make the little finger and index finger curve toward the middle finger. The middle and third fingertips can curve into each other, as well. See if yours do.

40. Roll up some burlap and lightly spray it with water. Tap the burlap gently against the clay to create a texture on the surface. The best technique is to press the burlap firmly but gently against the surface, roll it, and then lift: Press, roll, and lift.

The step-by-step lessons were designed to provide a simple foundation and starting point for sculpting a hand. Keeping it basic will keep you focused when sculpting a more expressive hand. Knowing some fundamentals will go a long way. Practice sculpting larger-than-life-size hands, and put more detail in if you choose. This particular hand gesture is obviously relaxed and simplistic in its development and is a good example for study purposes.

THE FOREARM

The lower arm is the most complex of the four limbs. The two bones of the lower arm, the ulna and radius, enable the arm to move in two directions at the same time. The ulna moves up and down, and the radius rotates inward. The large muscle group of the forearm (in the upper half of the forearm) supplies the power to the narrower muscles at the wrist, which activates the movement of the hand.

To get a feel for the structure, rest your arm at your side, and bend your lower arm up until your palm is parallel to, and faces, the ceiling and the elbow faces the floor. Place the fingers of your other hand on the wrist of your bent arm, like you’re taking a pulse. Slide your fingers along the flat surface, from your wrist up to the start of your upper arm, at the inner elbow joint. This surface is the long plane of the entire lower arm. It is wider at the elbow joint than it is at the wrist. Keep your fingers on the plane at the inner elbow joint, and rotate your arm 90 degrees, until your palm faces a wall. Don’t move your elbow. Now slide your fingers along the plane back to your wrist. Notice how the plane is still flat but begins twisting about halfway down the arm as you get closer to your wrist.

Next, continue to rotate your arm another 90 degrees (for a total 180-degree rotation from the original starting point) until your palm is facing the floor. Do this with out moving the elbow. Slide your fingers back and forth from the wrist to the inner elbow joint, along the twisting plane. The forearm muscles begin to change shape, becoming rounder as the arm rotates; however, the wrist remains relatively flat and rectangular before and during the rotation.

The wrist in the lower section of the forearm is a rectangular block. The top plane of the wrist block is broader than the side plane and is the same plane as the top of the hand. The plane changes direction as the wrist bends up and down. The bottom wrist plane is the same plane as the palm of the hand. The upper section of the forearm is somewhat triangular. The transition between the two areas happens somewhere in the middle of the forearm as it rotates.

When sculpting, determine the location of the bottom plane of the wrist in the pose, then locate the plane of the inner elbow of the forearm, and establish their positional relationship to each other. Create the planes of the clay wrist block with the wire loop tool, and tap them with the wood block. Build the rounded, triangular shape of the upper part of the forearm with small pieces of clay. Follow the twisting, flat plane from the wrist to the elbow, and look for the transition area between the two forms of the forearm. Build these forms with small pieces of clay and blend them together.

Here, the palm and inner elbow face the camera.

When the arm rotates 90 degrees from that starting position, the palm faces down toward the floor. The inner elbow still faces the camera.

When the arm rotates another 90 degrees (180 degrees from its starting position), the broad, flat bottom plane of the wrist now faces the wall.

The arm is a triangular form that’s wider at the elbow and narrower at the wrist. In the image above, a line marks the center of this plane from one X at the wrist to another at the inner elbow. This bottom plane of the forearm at the wrist is same plane as the palm and changes direction when the hand moves up and down.

When the arm rotates 90 degrees, the elbow itself does not move. Muscles at the elbow that attach to the thumb side of the wrist, however, cross over and follow the new position of the wrist. The muscles at the elbow attached to the wrist on the pinkie side of the hand roll under to follow the rotated position of the wrist. The side plane of the arm and wrist rotates from mid-arm. The lined area indicates the twisting side plane of the arm, wrist, hand, and index finger.

As you twist the clay arm another 90 degrees so that the palm and bottom plane of the wrist touch the base, the muscles stretch to accommodate the new wrist position. The radius bone completely crosses over the ulna. The side plane continues the twisting action.

As when sculpting the full figure or the hand, once the beginning block structure is established, you can start adding pieces of clay to the planes of the arm and wrist to give volume to the forms. Tap the clay with the wood block and rake with the wire loop tool to blend the forms as the narrower wrist transitions to the wider elbow.

To finish, tap the form with rolled-up burlap to create a final surface texture.