Beurre Manié and Slurry

Beurre manié= 1 part flour : 1 part butter (by volume)

Slurry = 1 part cornstarch : 1 part water (by volume)

Thickening Rule = 1 tablespoon starch will thicken 1 cup liquid

Beurre manié, or kneaded butter, is butter into which an equal volume of flour has been rubbed and kneaded, becoming an easy, effective way to thicken small amounts of sauces while also enriching them. Slurries, pure starch and water, may be quicker and more widely used, but they don’t enrich or add flavor—butter does. Beurre manié is especially suited to thickening pan gravies, small quantities of à la minute sauces, meat stews, fish stews, and the poaching liquid in which fish has cooked. It should be used à la minute, just before serving.

A slurry is a mixture of a pure starch, such as cornstarch or arrowroot, and water. It’s used to thicken sauces, a process often called lié ( jus de veau lié is veal stock thickened with a slurry). Slurries are excellent for last-minute thickening, especially of sauces. The thickening will break down after repeated or extended cooking, so it’s best to lié your sauce just before serving. You can use slurries to thicken larger quantities of liquid, such as soups, but this can create an unpleasant, overly gelatinized texture; roux is the recommended thickener for soups.

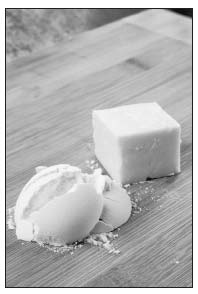

Flour and butter in equal volume are kneaded together to form beurre manié (“kneaded butter”), a paste that is whisked into sauces to both thicken and enrich them.

Most of the ratios in this book are measured in terms of parts by weight. This isn’t practical when working with the small quantities here. In fact, making slurry and beurre manié is easiest to do using volume measures, and because we do most of our thickening by eye, the thickening rule simply provides the guideline that 1 tablespoon of any starch, whether flour or a pure starch such as cornstarch, will thicken to a light sauce consistency of 1 cup of liquid.

Here, the ratio is helpful for those who aren’t familiar with slurries, but generally, it’s best to mix a slurry by sight—it should have the viscosity and appearance of heavy cream—and add it to the hot liquid until you’ve reached the desired consistency. As a rule, though, 1 tablespoon of cornstarch mixed with enough water to separate the starch granules will thicken to medium consistency 1 cup of water.

I use beurre manié to thicken any sauce that benefits from a little butter. Which is pretty much any sauce! If you had a little fish stock and cooked a piece of fish in the stock in a small sauté pan, you could simply remove the fish, swirl in some beurre manié and have an elegant sauce to go with your fish (some fresh thyme or tarragon and a squeeze of lemon would go a long way here). If you have some veal stock (or beef), sauté some mushrooms and add them to the stock, bring to a simmer, and add a little beurre manié (a tablespoon per ½ cup of stock) and you will have a lovely sauce.

To demonstrate the effectiveness and versatility of beurre manié, I’m choosing one of the most common and wonderful preparations known: roast chicken. And to underscore the wonders of using water as a stock base, I’ve built the stock-making process into the method itself, which happens after the chicken is cooked, while it’s resting.

Consistency is a critical factor in everything we eat. Beurre manié is one way we can regulate the consistency of liquids that add flavor and juiciness to our food. If you like it, make a cup or so by combining ½ cup of flour with a stick of soft butter, knead it to thoroughly distribute the flour, roll it in plastic wrap, and refrigerate until you need it. It will keep for a month refrigerated and for several months if frozen.

Roasted Chicken with Sauce Fines Herbes: A Lesson in Using Slurry or Beurre Manié

Here is a very basic but also elegant way to roast and serve a chicken, simple and economical enough for a weekday meal, but elegant enough to serve the most honored guests. I honestly don’t know if there’s anything better in the kitchen than the whole process of roasting a chicken and preparing a sauce while it rests. A whole chicken this size takes an hour to roast, which gives you plenty of time to make accompaniments (mashed potatoes and buttery green beans sprinkled with salt and lemon juice are my favorites).

I especially like the sauce method here because it doesn’t require chicken stock, only water (you will, in effect, be making your own quick stock right there in the pan you cooked the chicken in; though if you have some freshly made stock, perhaps from last week’s chicken, Stocks, that’s even better).

The main flavor of the sauce comes from the elegant mixture of herbs we call fines herbes (parsley, tarragon, chives, and chervil), dominated by the anise notes of tarragon and chervil. Don’t worry about the chervil if it’s not available to you, but then don’t skimp on the tarragon. Unless, of course, you don’t like tarragon! In that case, just use parsley and chives. You’ll need about a tablespoon of finely chopped herbs to finish the sauce, but save a few complete stems to add to the sauce while you’re cooking it.

The best way to roast a chicken this size is in very high heat, at least 450°F. If your oven isn’t clean, this can result in a smoky kitchen if you don’t have an exhaust hood, but I think it’s worth it for the beautiful golden brown skin and the incomparably juicy chicken. It’s important also to salt the chicken aggressively with kosher or coarse-grained salt. I prefer roasting the chicken in a medium cast-iron skillet or any ovenproof sauté pan just large enough to hold the bird. It’s just the right size for making a pan sauce once the bird is roasted.

The sauce is made by quickly cooking the onion and carrot in the pan with the skin that has stuck to it, any neck or gizzard that you found in the bird, and the wing tips from the roasted chicken, first in wine until that is reduced and the pan is crackling and then water, developing great flavor by reducing the liquid all the way down. (When using wine, it’s important that it’s a wine you would happily drink, not so-called cooking wine.)

The sauce is strained into a small clean pan, reheated and thickened with a little beurre manié, and finished with the herbs.

1 roasting chicken (3 to 4 pounds)

Kosher salt

1 tablespoon butter kneaded with 1 tablespoon flour or

1 tablespoon cornstarch mixed with 1 tablespoon water

1 tablespoon finely chopped parsley, tarragon, chervil, and chives (one or any combination of these), with several stems of each reserved

1 medium yellow or white onion, thinly sliced

1 large carrot, thinly sliced

1 cup white wine

2 teaspoons minced shallots

Preheat your oven to 450°F (give it at least 25 minutes to get up to temperature).

Rinse and dry your bird, and keep the neck and any other innards except the liver (discard it or save it for another use). I like to truss the bird, pulling its legs together with butcher’s string, crossing the two ends of the string and pulling them around the chicken, over the leg and wing, and tying the two ends at the neck; this results in a pretty cooked bird, one that rests more efficiently while you’re making the sauce, with juicy white meat; while it’s not strictly necessary, it’s a definitively better roasted bird that comes out of the oven. A bird that’s not trussed, as Bob del Grosso discovered while teaching at the CIA, can be as much as 10 percent lighter from water loss; trussing, he explains, closes up the body cavity, reducing airflow through it, and thereby reducing water loss. If you are not trussing the bird, I recommend stuffing the cavity with onion, a halved lemon, and any extra herbs you may have.

Salt the bird heavily with kosher salt; you’ll need about a tablespoon in all; the bird should look almost as though it’s got a crust of salt on it. Place the bird in an ovenproof skillet and pop it into the oven for 1 hour. (Prepare the accompaniments now and the remaining ingredients for the sauce.)

In a small bowl, combine the butter and flour, kneading it with your fingers until it becomes a uniform paste. Refrigerate it until you’re ready to finish the sauce. Or combine the cornstarch and 1 tablespoon of water in a small bowl and set it near the stovetop.

Pick enough leaves of the parsley, tarragon, and chervil, if you’re using it, and enough stems of chives so that you will have about a teaspoon of each once they’re finely minced. Mince them and combine them. Reserve a few leafy stems of parsley and tarragon and a few stems of chives.

When the chicken has cooked for 1 hour, remove it from the oven. Stick a wooden spoon or other tool into the carcass to lift the bird out of the pan, allowing the skin to remain stuck to the pan. Set the bird on a cutting board or plate (it will release juices as it rests—you’ll add these to the sauce). Place the pan over high heat to cook some of the juices down, and brown the skin that’s stuck to the pan for a couple of minutes (be careful—the pan handle will remain very hot; keep a sturdy, dry kitchen towel over it). Remove the tips of the wings from the chicken and add them to the pan. Pour off all but 2 tablespoons of fat from the pan, return the pan to the heat, and add the onion and carrot and reserved herb stems; cook these for about a minute over high heat. Add the wine and boil the wine down, scraping the bottom of the pan with a flat-edged wooden spoon to get up all the skin and browned juices. When the wine is nearly gone, the pan will begin to crackle as the last of the wine cooks off. Stir the onion and carrot and chicken, cooking them more to brown them slightly. Add about a cup of water and repeat the reduction (use hot water to speed up the process a little). While this last reduction is happening, sweat the shallots in a film of canola oil or butter just to soften. When the water in the pan is gone and the pan is crackling, add 8 ounces of water along with the juices from the chicken (you can separate the legs from the carcass to get more juices), bring it to a boil for about a minute, and strain it into the saucepan with the shallots. Bring the sauce to a simmer and add the beurre manié, whisking or stirring until it is completely melted and the sauce has thickened. Remove it from the heat.

Remove each half of breast from the bird, keeping the wing attached (drawing your knife along either side of the breastbone, follow the wish-bone down to the wing joint and cut through the joint). Remove the legs from the chicken and separate the legs and the thighs. Add the fines herbes to the sauce and rewarm as necessary. Serve with the chicken. Don’t throw away the bones!

YIELD: SERVES 4