The Noble Sausage

Sausage = 3 parts meat : 1 part fat

Sausage Seasoning = 60 parts meat/fat : 1 part salt*

Sausage is one of the culinary glories when it’s made and cooked right—a package of inexpensive trim, some fat, some seasoning that can be unparalleled in its deliciousness, in its ability to satisfy. A technique born of economy that results in the sublime. Truly, my respect for sausage knows no bounds.

Sausage can be made with just about anything you can fit into a casing (vegetables, rice, eggs, legumes, offal, blood), but sausage doesn’t necessarily have to fit in a casing to be sausage—patties are part of the sausage tradition (relatives of the crepinette, which is a patty wrapped in caul fat) and free-form sausage is common as well in pasta, soups, and stews. Pot stickers use a dough to enfold sausage. So, often, do raviolis. The above ratio concerns itself with traditional sausage, that is, sausage made with meat. Chicken, lamb, beef, pork, and venison all make wonderful sausages (fish does, too; see Mousseline, Mousseline). But the keys to a great sausage are first and foremost to blend the right proportion of meat to fat, and second to add the optimal proportion of salt to that meat-and-fat mixture. The advantage of the ratio here is that it can be scaled up or down as you need it. It’s especially handy if you simply want to make a small portion, say 8 or 9 ounces (ground or chopped with ¾ teaspoon of salt and some garlic and herbs), to enhance a pasta or soup.

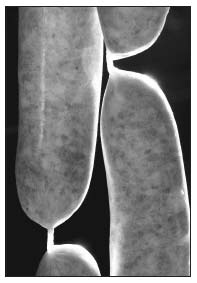

To ensure juiciness, sausages should be between 25 and 30 percent fat. Sausage may be most familiar to us when stuffed into casing, as with this garlic sausage, but remember that sausage can be stuffed into pasta or dough or can be shaped and sliced or used loose.

Without fat, sausages are dry and unpleasant. There is no such thing as a good, lean sausage. When chicken sausage tastes delicious, it’s because it has the right amount of fat in it. (Be aware that store-bought chicken and turkey sausage are often made with what’s called “mechanically separated” meat—meat and other fragments whipped off bird carcasses in a big spinner.) Commercial sausages that are both delicious and lean typically have some kind of chemical shenanigans going on in them to compensate for the lack of fat. Stick to natural foods, and you can eat fat and salt in comfortable proportions.

That is not to say that you can’t use healthy techniques in your own sausages to reduce fat somewhat without compromising succulence. Vegetables and fruits can add moisture and flavor to sausages—roasted red peppers, onions, mushrooms, tomatoes, and apples make great additions to a sausage. Liquid fat, such as a flavorful olive oil, can be added to sausage, as can a wine or rich stock. But in the end, it’s a fact we must embrace: the excellence in a sausage begins with the proper ratio of meat to fat.

That ratio is 3 to 1, 3 parts meat, 1 part fat. Ideally, 30 percent of a sausage is fat. This ratio amounts to 4 total parts with one of them, or 25 percent, being fat. The missing 5 percent is typically part of the meat that’s being used—pork shoulder, for instance, or boneless chicken thighs, a great meat to transform into sausage. Indeed, some cuts are very lean; others are fatty, so some amount of eyeballing is required. Use your common sense. If you wanted to make a beef sausage with eye of round, venison, or other lean meats, you’d need a little bit more fat than the 1 part to 3 parts meat. Pork shoulder can come with the perfect proportion of fat already in it, so additional fat may not be needed when using pork shoulder. Thus, this ratio is one you almost always need to gauge with a scale and some common sense. If you’re using very lean chicken, you’ll need that full amount of fat. If you’re using meat off beef short ribs, you won’t need any.

The fat of choice is pork back fat, fat from the back of the hog—it’s the fat that rims your pork chops but can be as much as 2 inches thick—it’s very pure and supple and excellent for all pâtés and sausages. It can be ordered from your butcher or grocery-store meat department. And if it comes from a farm-raised pig, it’s better for you than the more saturated fat from beef or lamb.

The next critical factor in creating the perfect sausage is salt. Sausages must have salt. Indeed, the word sausage derives from the Latin for salt. Originally, salt was the primary preservative element in sausage—it reduces bacteria activity—which was often dry cured and thus could be kept indefinitely. It remains so today in dry-cured sausages, but it is also the primary flavor enhancer in fresh sausages.

Never use iodized salt, which adds an acrid chemical flavor to food. Use kosher or sea salt only. Salt your meat well in advance of grinding it, so that the salt dissolves and penetrates (it will also help dissolve some of the meat protein, which will give the finished sausage a good bind and texture).

The ratio is .25 ounce of salt per pound of meat and fat, or about 1 ½ teaspoons of Morton’s kosher salt. Because salt is so important to get right, it’s best to weigh your salt—a tablespoon of fine sea salt, coarse sea salt, Morton’s kosher, and Diamond Crystal kosher all have different weights. Morton’s kosher is the closest to an even volume-to-weight ratio (a cup of Morton’s weighs about 8 ounces); the volume measurements in the following sausages require Morton’s kosher salt. If you’re uncertain about the salt quantity you’re adding, it’s best to err on too little salt than too much.

There are a few important steps to making excellent sausage beyond the ingredients list. Sausage benefits from early seasoning. If possible, dice your meat and fat and toss it with the salt and seasonings the day before you grind it.

In terms of the actual making of the sausage, I’ve found there’s one component that is more important than any other: keeping your meat cold at all times. This means if you’re making sausage in a hot kitchen, it’s prudent to partially freeze your meat before grinding it, and if you’re not mixing it right away, keep it thoroughly chilled until you do.

After you’ve ground it, thoroughly mix it in the mixing bowl using a paddle to develop the protein myosin, which helps it all stick together. This also allows you an opportunity to add more flavor in the form of wine or olive oil (liquid also helps to distribute the seasonings and results in a juicier finished sausage).

The final element to the perfect sausage is cooking it right, taking it to the right temperature. The best way to gauge a sausage’s temperature is with an instant-read or cable thermometer. Sausages are among the most abused foods when it comes to cooking them. They are almost always overcooked, and this can ruin a sausage. Pork sausages should be cooked to 150°F before being removed from the heat, and poultry-based sausages should be cooked to 160°F. If they are in a casing, they should be cooked in a way that browns them for flavor and texture, but remember, they cook best in moderate heat. Too much heat on a grill or in a blazing-hot pan will overcook the outside before the inside is warm, and often will split the skin, releasing the juices and fat that make sausage taste good in the first place.

Apart from these critical steps the rest is seasoning, and this is up to the cook. When creating your own sausage, stick to pairings you know go well together. Chicken and tarragon or fines herbes go well—they would be excellent in a fresh chicken sausage. Dill is an herb you wouldn’t normally pair with lamb. So if you were making a lamb sausage, you wouldn’t combine it with dill; rosemary and garlic go well with lamb—so they’d also make great seasonings for a lamb sausage. Fresh black pepper and garlic alone is delicious. For rich meats such as venison, sweet spices go well. Fresh herbs are excellent in most sausages. For more exotic seasonings, you might look to other culinary traditions—Southwestern (cumin and dried chillis, roasted fresh peppers, cilantro) or Asian (scallions and ginger). Once you get the ratio right, there’s no end to the kind of sausages you can create.

The following sausages are a few of the possible variations. Instructions assume you will be stuffing the meat into casings and twisting it into 6-inch links, but this is not strictly necessary. Loose sausage, sautéed in coarse chunks or as patties, tastes just as delicious. Loose sausage is great with all grains and legumes and pasta—everything from couscous to navy beans to barley to spaghetti.

Spicy Garlic Sausage

Sometimes I wonder if God didn’t create garlic specifically for sausage only to find out later that it went well with a lot of other things, too—because garlic and sausage are simply one of the great pairings. You almost don’t need anything else, but I like one other element, either smoke or, here, heat. I make sausage in 5-pound batches, since that’s the maximum that will fit in the 5-or 6-quart mixing bowl standard for most standing mixers; if you’re going to make sausage, you might as well make a good amount. Sausage freezes well and will keep for a month or two in the freezer if well wrapped. Note that this is not a 3 : 1 ratio of meat to fat; because pork shoulder is fatty to begin with, there will be about 1 1/3 pounds of total fat. Again, strive for fat that equals 30 percent of the total weight, 24 ounces in 5 pounds (80 ounces).

4 pounds boneless pork shoulder butt, diced

1 pound pork fat, diced

1.25 ounces kosher salt (about 2½ tablespoons)

1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons dried red pepper flakes

2 tablespoons minced garlic

1 cup good red wine, ice cold

10 feet hog casings, soaked in tepid water for at least 30 minutes and rinsed (optional)

Toss the meat, fat, salt, black pepper, red pepper flakes, and garlic together until evenly mixed. Cover and refrigerate for 2 to 24 hours, until the mixture is thoroughly chilled. Alternately, place the mixture in your freezer for 30 minutes to an hour, until the meat is very cold, even stiff, but not frozen solid. Set the mixing bowl in a larger bowl of ice and grind the meat through a small die into the bowl.

Using the paddle attachment for a standing mixer (or a metal or strong wooden spoon if mixing by hand), mix on low speed or stir for 30 seconds; then add the wine and increase the mixing speed to medium and mix for 1 more minute or until the liquid is incorporated and the meat looks sticky.

Fry a bite-sized portion of the sausage and taste (refrigerate the sausage mixture while you do this and set up your stuffing equipment). Adjust the seasoning if necessary and repaddle to incorporate additional seasoning.

Stuff the sausage into the hog casings if using and cook to an internal temperature of 150°F, about 10 minutes in a sauté pan over medium-low heat or roasted in a 350°F oven.

YIELD: 5 POUNDS OF SAUSAGE, ABOUT TWENTY 6-INCH LINKS

VARIATIONS ON SPICY GARLIC SAUSAGE

- Hot Italian sausage. Add 2 tablespoons fennel seeds, 3 tablespoons sweet paprika, and ¼ cup chopped fresh oregano to the spicy garlic sausage for traditional Italian sausage—use it loose with pasta and tomato sauce or make pasta dough and use it to stuff raviolis.

- Sweet Italian sausage. Omit the chilli flakes and add 2 tablespoons sugar, 2 tablespoons fennel seeds, 3 tablespoons sweet paprika, and ¼ cup chopped fresh oregano.

- Breakfast sausage. Omit the chilli flakes; add ¼ cup each peeled and grated ginger and minced sage.

- Duck or turkey sausage. Replace the pork shoulder with diced duck or turkey (leg and thigh meat are preferable). Reduce the chilli flakes by half and add ½ cup minced sage.

- Venison. Venison makes an excellent sausage. When making venison sausage, discard the venison fat and use a full proportion of pork fat. Use half the chilli flakes and add ½ cup minced onion, ½ teaspoon each allspice and nutmeg, and 2 teaspoons each paprika and black pepper.

- Mexican chorizo. Omit the chilli flakes and add 1 tablespoon each ancho powder and chipotle powder, 1 ½ teaspoons cumin, and ½ cup chopped oregano.

- All-beef sausage. Replace the pork and fat in the spicy garlic sausage with meat and fat cut from beef short ribs; this can be stuffed into hog casings or, to forgo pork products altogether, into sheep casings.

- Chicken sausage. Replace the pork shoulder butt with boneless, skinless chicken thighs.

Lamb Sausage with Olives and Citrus

Sausage can be made from just about any meat, and the way to create sausages of your own is to determine which meat that is and then use flavor pairings that you know work well. Here I combine lamb, olives (my favorite are Castelverano), and citrus, which is a great combination no matter the form of the meat. There’s less salt added because the olives add their own salt. Because the salinity in olives varies, it’s important to pay careful attention to the seasoning.

4 pounds lamb shoulder, diced

1 pound pork fat, diced

1 ounce salt (about 2 tablespoons Morton’s kosher salt)

Zest of 1 orange

Zest of 1 lemon

1 teaspoon black peppercorns, toasted and finely ground

3 tablespoons coriander, toasted and finely ground

¼ cup lemon juice

½ cup orange juice

¼ cup extra virgin olive oil

¼ cup mint, minced

1 ½ cups olives, chopped (use a variety of good, flavorful olives)

10 feet hog casings, soaked in tepid water for at least 30 minutes and rinsed (optional)

Combine the lamb, pork fat, salt, zests, black pepper, and coriander and toss well to distribute the seasonings. Cover and refrigerate for at least 2 hours or overnight.

Combine the lemon and orange juices and the olive oil and chill this mixture as well so that it is very cold when you use it.

Grind the lamb mixture through a small die into a bowl set in ice. Put the ground meat and mint in the bowl of a standing mixer with the chopped olives and mix on low for 30 to 60 seconds. Turn the mixer to medium-high and slowly add the juice-and-olive-oil mixture. Mix until it’s well incorporated and the meat has an almost furry texture. Be sure to get some olives in the cooked portion you taste to check for seasoning, because they can bring a lot or a little salt, depending on how they were cured.

Stuff into the hog casings if using and twist into 6-inch links, shape into patties, or store as is to use loose. Cook for about 10 minutes in a sauté pan over medium-low heat or roast in a 350°F oven.

YIELD: 5 POUNDS OF SAUSAGE, ABOUT TWENTY 6-INCH LINKS

Chicken Sausage with Basil and Roasted Red Peppers

I like to offer a chicken sausage for a couple of reasons. First and foremost is to prove that it can and should be every bit as decadent as a pork sausage and, second, that it can be even more flavorful than pork sausage. This is a variation of a sausage Brian Polcyn created for Charcuterie, but there’s no reason you couldn’t vary it in any direction you wanted—with the olive-citrus seasoning, as in the lamb sausage recipe above, or with garlic and pepper, or fines herbes. A chicken sausage, made with readily available boneless thighs, is a great vehicle for flavor.

3 ½ pounds boneless, skinless chicken thighs, cubed

1 ½ pounds pork fat, cubed

1.25 ounces kosher salt (about 2½ tablespoons)

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon garlic, minced

½ cup tightly packed basil, chopped

½ cup tightly packed basil, chopped

½ cup diced roasted red pepper (1 or 2 red peppers, charred, peeled, and seeded)

¼ cup red wine vinegar, chilled

¼ cup extra virgin olive oil

¼ cup dry red wine, chilled

10 feet hog casings, soaked in tepid water for at least 30 minutes and rinsed (optional)

Toss the chicken, fat, salt, pepper, garlic, basil, and red pepper together until evenly mixed. Grind the mixture through a small die into a bowl set in ice.

Using the paddle attachment for a standing mixer (or a metal or strong wooden spoon if mixing by hand), paddle on low speed or stir for 1 minute; then add the vinegar, oil, and wine and increase the mixing speed to medium and mix for 1 more minute or until the liquid is incorporated.

Fry a bite-sized portion of the sausage, taste, and adjust the seasoning if necessary.

Stuff the sausage into the hog casings if using and twist into 6-inch links. Sauté, roast, or grill over medium-low heat to an internal temperature of 160°F.

YIELD: 5 POUNDS OF SAUSAGE, ABOUT TWENTY 6-INCH LINKS

Fresh Bratwurst

There are as many forms of bratwurst in Germany as there are salamis in Italy. The brats I’ve come to love in the United States are dominated by sweet spices such as nutmeg. I’m also adding some marjoram, which is common in the Silesia region of Germany, to this recipe, because marjoram is an underused herb and it’s a favorite of my partner in charcuterie, Brian Polcyn, who taught me the finesse elements of making sausage.

4 pounds pork shoulder, diced

1 pound pork backfat, diced

1.25 ounces kosher salt (about 2½ tablespoons)

2 teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon ground nutmeg

1 tablespoon ground ginger

¼ cup chopped marjoram

½ cup white wine, chilled

&10 feet hog casings, soaked in tepid water for at least 30 minutes and rinsed (optional)

Toss the meat, fat, salt, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, and marjoram together until evenly mixed. Cover and refrigerate for 2 to 24 hours, until the mixture is thoroughly chilled. Alternately, place in your freezer for 30 minutes to an hour, until the meat is very cold, even stiff, but not frozen solid.

Grind the mixture through a small die into the mixing bowl of a standing mixer set in a bowl of ice.

Using the paddle attachment for a standing mixer (or a metal or strong wooden spoon if mixing by hand), mix on low speed or stir for 30 seconds; then add the wine and increase the mixing speed to medium and mix for 1 more minute or until the liquid is incorporated and the meat looks sticky.

Fry a bite-sized portion of the sausage and taste (refrigerate the sausage mixture while you do this and set up your stuffing equipment). Adjust the seasoning if necessary and repaddle to incorporate additional seasoning.

Stuff the sausage into the hog casings if using and twist into 6-inch links. Cook to an internal temperature of 150°F, about 10 minutes in a sauté pan over medium-low heat or roasted in a 350°F oven.

YIELD: 5 POUNDS OF SAUSAGE, ABOUT TWENTY 6-INCH LINKS

Beyond the Noble Sausage

Once you know the meat-fat ratio and the salt-per-pound ratio, you can transform any meat into sausage, but that doesn’t mean you should stop there. There are endless preparations that use ground meat that we don’t think of as sausage. Pot stickers are filled with what is, in effect, sausage—a ground meat stuffing, or farce. Meat loaf is nothing more than a free-form sausage. A pâté en terrine is a basic sausage with lots of extra seasoning and aromatics and interior garnish—mushrooms and herbs and pistachios—spread in a terrine mold, covered, and baked in a water bath like a custard to a temperature of 150°F (or 160°F if using chicken). Meatballs are a form of sausage. I’m not going to say that hamburgers are sausage, but, well, they are the same idea. In fact, it’s a great practice to season your hamburger meat a day ahead of cooking it: follow the .25 ounce of kosher salt per pound, and you will have perfectly seasoned burgers.

VARIATIONS BEYOND SAUSAGE

- Make extraordinary pot stickers by adding minced garlic, ginger, and scallion to a basic pork sausage (a dough can be made by mixing 1 part cold water into 2 parts flour—3 ounces water and a cup of flour—until a dough is formed; or you can use wonton wrappers if you wish). Fry the pot stickers in a film of oil, then add a couple of cups of Everyday Chicken Stock, cover, and simmer until done, about 15 minutes.

- Stuffed peppers. Peppers were practically designed to carry sausage. Fill them with any kind of sausage and grill (or roast) them until the sausage is done (150°F; 160°F for chicken sausage). It’s best to use banana peppers or ones that don’t require a boatload of sausage. You want a good ratio of pepper to sausage). Another option is to scoop the seeds out of a halved zucchini, stuff that with sausage, and grill (or roast).

- Make meatballs. To a basic grind of beef with 25–30 percent fat, add .25 ounce of salt per pound; ½ cup of diced onion sautéed with a couple of cloves of minced garlic; a couple of pieces of day-old bread, chopped, soaked in milk, and squeezed out; an egg; and ¼ cup of chopped oregano, if you wish. The key to good meatballs, unlike a sausage, which is thoroughly mixed, is not to overmix it. Gently combine the ingredients, just so they are evenly distributed and form into balls. Flour them and panfry.

Make the meatball mixture using a combination of beef, veal, and pork, form into a loaf, and bake at 350°F to an internal temperature of 155°F, for meat loaf. - Keftedes, a version of Greek meatballs. Working with Cleveland chef and friend Michael Symon, I learned his preference for meatballs, which he serves either as a main course or as an hors d’oeuvre—seasoning beef or lamb with black pepper, coriander, garlic, and lemon zest. He serves them panfried with lemon zest, torn fresh herbs, mint, cilantro, and some crumbled feta cheese.

- Stuffed flank steak. Use the keftedes or meatball mixture to roll inside a flank steak, tie the steak, and braise in a loaf pan in veal stock until the beef is fork tender. Skim the fat from the sauce and reduce the sauce, whisking in a tablespoon or two of butter (or beurre manié, just before removing it from the heat, and serve with the sliced meat.