Crimes of the Heartless: Empathy Disorders, Part One

I’ve suggested that one reason that so many people love Austen is that, like Shakespeare, she “holds the mirror up to nature,” portraying a broad range of human feelings that we all recognize: happiness, excitement, anger, embarrassment, fear, and, above all, love. And so we feel empathy from Austen herself, the sense that she takes our perspective cognitively and emotionally; we have the feeling of “feeling felt.”* Unlike Shakespeare, however, Austen doesn’t display an equally broad range of human behavior: She avoids the atrocities that our kind are all too capable of committing. I can read Austen at bedtime without fear of nightmares because I know I’ll encounter a relatively safe world.

Yet, while Austen doesn’t portray the worst of human behavior, she nevertheless gives us the sense that she’s encompassed the grim side of human nature. She achieves this Shakespearean inclusiveness by gesturing toward dangers that don’t actually happen, leaving it to her readers to imagine tragic outcomes and gory details and to feel relieved that these haven’t happened. We recognize the potential for trauma with a capital “T,” but are then returned to the comfort of the sheltered world we presumably share with her characters.

Emma does this particularly well. Take Miss Bates. As an aging single woman without employment or resources, a bleak and impoverished future looms on the horizon for her. We can imagine her losing her home, living in a poorhouse where conditions are harsh, or in a cottage without a warm fire or enough to eat, comforts she’s used to. Or she might have to become a poor relation in a home where she’s resented and disrespected. It’s hard to say which of these options is worse, for emotional pain can be just as hard to bear as a lack of creature comforts. Fortunately, our Miss Bates can depend on the kindness of neighbors to assure her an old age with dignity and ease.

We can paint the same kind of bleak future for Jane Fairfax, should she be forced to work as a governess, a position akin to that of a poor relation but with even greater potential for exploitation. But Jane too is rescued by Austen’s plot, marrying the wealthy Frank Churchill. These averted futures invoke the sad stories of many others not so fortunate, of real and fictional people who lurk beyond the boundaries of Austen’s pages.

Harriet’s encounter with the gypsies performs a similar literary vanishing act. Harriet is walking alone along country roads when she encounters a band of gypsies who ask for money, which she gives. But this isn’t enough; as the narrator tells us, “her terror and her purse were too tempting, and she was followed, or rather surrounded by the whole gang, demanding more.” The threat of rape is the unspoken danger here, a threat conveyed with symbolism. You don’t have to be a Freudian to see that the purse can be associated with female genitals. The “more” that the gang demands might simply be more money, but the thinly veiled demand is for more than money.

Frank Churchill comes to the rescue, which, of course, prompts Emma to think of a match between them. We’re safely back in the sheltered world of romantic comedy, but again, we’ve caught a glimpse of the very real threats that lie beyond its borders. This is brilliant on Austen’s part—she lets us glimpse true evil because it’s important to an understanding of human nature, but she keeps us safe from witnessing its consequences.

Austen’s technique of invoking terror only to return us to the comfortable world of provincial, middle-class England is of course writ large in Northanger Abbey. Catherine Morland, the novel’s main character (or “heroine” as Austen somewhat ironically calls her), is so heavily influenced by her reading of Gothic horror novels that she becomes convinced that her host, General Tilney, has either murdered his wife or is keeping her prisoner in a secluded part of his home. The Tilney residence is a former abbey, the perfect setting for a Gothic scenario. Catherine discovers her mistake—there’s no madwoman in the attic—which is enough to make her blush heartily in private. But to her dismay, Henry Tilney, the general’s son and the man she loves, guesses her folly when he finds her lurking in the corridors of the unused wings of the abbey, looking for evidence. He scolds her for having such ludicrous thoughts:

If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to—Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English: that we are Christians. Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you—Does our education prepare us for such atrocities? Do our laws connive at them? Could they be perpetrated without being known, in a country like this, where social and literary intercourse is on such a footing; where every man is surrounded by a neighbourhood of voluntary spies, and where roads and newspapers lay every thing open? Dearest Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?

Henry says what we know (or come to know) as readers of Austen’s fiction: We’ll encounter a safe and predictable world in her pages, a world in which people by and large get what they deserve and where people are, by and large, shielded and safe.

Catherine’s humiliation conveys a familiar moral, usually directed at women in the novels of the period: Don’t give free reign to the imagination because imagination often misleads us. Better to trust in reason. Such was the creed of Samuel Johnson, one of Austen’s much-admired literary predecessors.

But Northanger Abbey’s other observation is the more important and original one, which, apart from Austen’s superb writing, gives this novel an edge over most other literary assaults on the dangers of the imagination: The character traits that make a man capable of murdering his wife or imprisoning her in his attic enable people to commit all manner of cruelties, large and small. When the general summarily dismisses Catherine from his home upon discovering she’s not an heiress, sending her on a full day’s journey by public coach without money or a servant, Catherine herself comes to realize this truth: “[I]n suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty.”

Catherine is correct about “the banality of evil,” to use the apt expression of twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt. For evil is indeed what Austen is considering here as well as in other novels, and this includes both passive sins of omission on the part of a society that doesn’t take care of its vulnerable members, as well as actual crimes such as rape and murder, flashed before our eyes as potentialities. Austen brilliantly realizes that evil is not only a moral problem, but a psychological one as well: In her view, evil is the failure or absence of empathy. All of Austen’s novels focus to some extent on whether or not people are able to take the perspective of others, emotionally as well as cognitively. While not all her characters with limited abilities for mentalizing are bad (think of Mr. Woodhouse), her “evil” people are self-centered people, and such selfishness involves, above all, an inability or a refusal to empathize with others.

SUBJECTS VS. OBJECTS

Neuroscientist Simon Baron-Cohen also takes the view that a deficit of empathy is the core characteristic of evil, supporting his findings with a knowledge of the mind-brain that was obviously unavailable to Austen. In his view, experiencing empathy doesn’t necessarily lead to helping actions, and the absence of empathy doesn’t always result in dire consequences, but a lack of empathy is the essential quality shared by all who hurt others.

This is because such a lack allows people to view others as inanimate objects rather than as living beings. Empathy, which involves feeling and thinking from another person’s perspective, is what makes people real—alive—to us. If you don’t grasp other people’s emotions in this intuitive, personal way, if you don’t take their perspective both emotionally and cognitively, they’ll remain “unreal” to you; you might know intellectually that they have thoughts and feelings, but you won’t live that knowledge, feeling it in your bones and, hopefully, expressing it in your behavior. At this point, people, and other living creatures, become equivalent to objects.

And so we’re capable of evil, of hurting or destroying others, only when we deny or fail to perceive the feelings of those who are the targets of our malice; they become the “objects” of our cruelty in more than one sense. The Golden Rule, seen as the ground of moral action in many religions and traditions, acknowledges this insight with its famous mandate to take a third-person perspective: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” If you put yourself in the place of another, you’ll only practice behavior that you’d be willing to endure yourself. Once you identify with someone in this way, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to inflict pain.

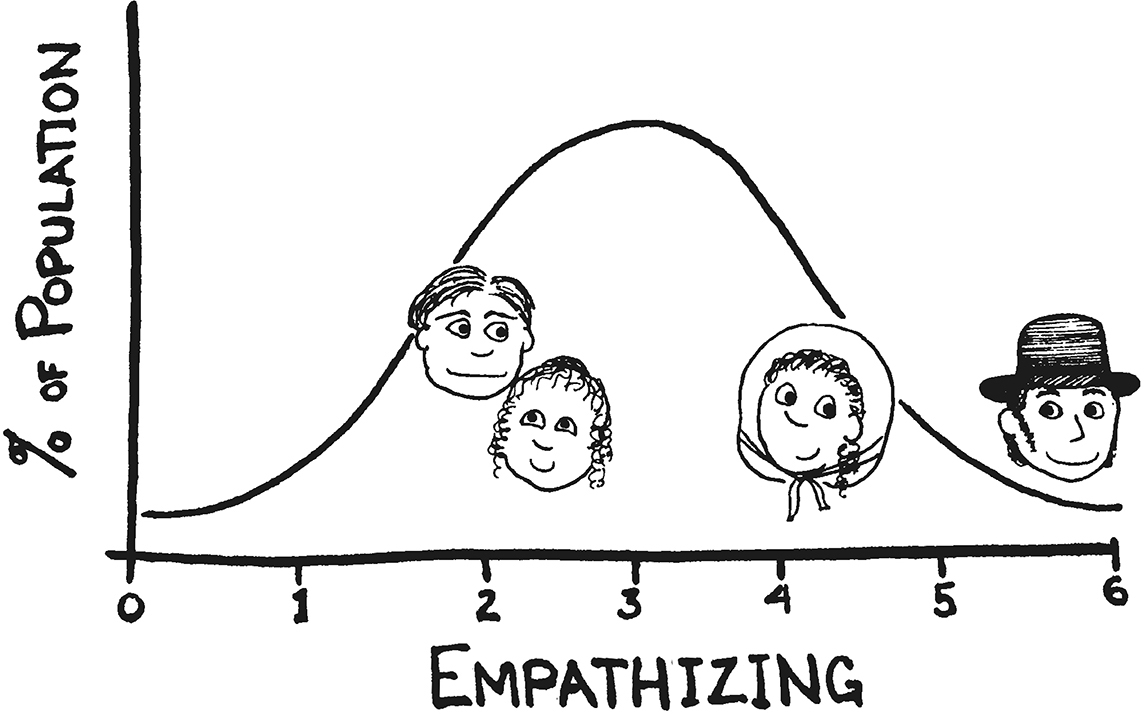

Of course, very few of us can be empathetic, truly conscious of other minds and hearts, all of the time. Emma is basically a good, kind person, but her empathy is definitely off-line when she insults Miss Bates. Nevertheless, within the parameters of such normal fluctuations, people possess empathy to greater and lesser degrees, with some people falling in the high-empathy and some in the low-empathy range. Baron-Cohen has formulated an empathy spectrum and a questionnaire to measure the extent of a person’s capacity for empathy, their “empathy quotient.” He has devised a simplified version of the empathy quotient scale, which has seven settings instead of the eighty-one of the EQ questionnaire: from zero (zero empathy) to six (highly empathetic). Like the EQ, this measures the “Empathizing Mechanism,” the degree to which a person is capable of empathy.

Let’s say we evaluated characters in Emma using the simpler Empathizing Mechanism scale. Mr. Knightley would likely receive the highest score, a Level 6, because he’s one of those “individuals with remarkable empathy who are continually focused on other people’s feelings, and go out of their way to check on these and to be supportive.” Emma would score well on the test, but would place at Level 5, “not constantly thinking about others’ feelings [but] others are nevertheless on their radar a lot of the time.”† The Eltons would place in the lower ranges of the scale. Most characters, and indeed most people, would place within the middle range. (For the statistically minded among you, this creates a bell curve.)

However, some fictional people, just like some real people, are unable to feel empathy. They have what Baron-Cohen characterizes as empathy disorders. These people divide into two basic types, those who do harm, who are capable of evil (he calls these “zero negative”), and those who lack empathy but are benign (“zero positive”). Zero positive refers to autistic people, while zero negative refers to those who suffer from what are called “Cluster B personality disorders” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), the diagnostic bible of the mind-brain sciences in the United States.

While all personality disorders are characterized by blunted affect and severe deficits in the ability to relate to others—a defective social mind-brain—in Baron-Cohen’s view, lack of empathy is the defining feature of the Cluster B disorders. These are borderline personality disorder (BPD); antisocial personality disorder (APD), also called sociopathy and psychopathy; and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). In the individual descriptions of these disorders, DSM-5 either states explicitly or implies that lack of empathy is a characteristic. In the trait-based “experimental” chapter on personality disorders, which is included in a section on emerging measures and models, but which will likely replace the current syndrome-based version, empathy is listed as one of the defining criteria for all the personality disorders.

Like so many of our social capacities and temperamental characteristics, the features that characterize personality disorders, including empathy, are on a continuum with ordinary personality traits. A person might be cold and deficient in empathy, like Mr. Elton, but lack the severe impairment that characterizes the Cluster B personality disorders. The Empathy Quotient questionnaire usually reveals this difference, if people answer honestly, that is—sociopaths and psychopaths are prone to lie. Disorders are distinguished from traits by their consistency, duration, and intensity—the extent to which they are enduring and inflexible character patterns of inner experience and behavior that differ markedly from cultural expectations, and which create distress or impair functioning in one or more areas: social, occupational, emotional or cognititive.

All of Austen’s characters who are diagnosable with empathy disorders demonstrate such consistency and degree of impairment. They exhibit the defining characteristics of their disorders over a long period of time, and they’re compromised both cognitively and emotionally. Those characters who are just insensitive or who have questionable morals lack this consistency and severity of symptoms.

Cluster B personality disorders (zero-negative empathy disorders) are disorders of the attachment system. (It’s likely that most personality disorders fit this category.) Borderline and narcissistic personality disorders involve insecure attachment, while antisocial personality disorder (psychopathy or sociopathy) means a person doesn’t attach at all. In addition to zero empathy, people afflicted with these disorders also have poor powers of mentalization and self-regulation, with the exception of a certain kind of ASD (high Machiavellian—see below), in which case these powers are learned using top-down, cognitive processes. Healthy intimacy, mentalizing, and emotional regulation are precisely the functions that the attachment system builds according to the theorists on attachment considered in earlier chapters: Bowlby and Ainsworth (close relationships), Fonagy (mentalization), and Schore (regulation).

Those who possess a secure attachment style have a “good-enough” capacity with regard to each of these functions. For this reason, Baron-Cohen characterizes secure attachment as “an internal pot of gold,”‡ which gives a person the ability to deal with adversity and setbacks, and to form intimate, affectionate, trusting relationships with others. People with severely deficient attachment experiences usually lack this characterological wealth; they’re bankrupt socially and emotionally.

AN “EDGY DISORDER”: BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) got its name (first used in 1938) from twentieth-century psychiatrists in the United States who believed the condition was on the border between neurosis and psychosis—between impairments in functioning and actual delusions. While it’s true that a person with BPD has a severely distorted view of relationships, and so of reality, BPD is no longer considered a psychosis. But it’s nevertheless an “edgy,” volatile disorder, characterized by insecurity, impulsivity, and a severe deficit in powers of self-regulation.

These traits lead to a pattern of instability in relationships. With those close to them, people with BPD oscillate between idealizing and devaluing, loving and hating; they might be affectionate one moment and enraged the next. Uncontrollable rages characterize the condition. Confidence might alternate with feelings of worthlessness, although such confidence is likely to be grandiose—inflated and unrealistic. People with the disorder tend to engage in risky behavior.

James Masterson, a psychiatrist who specialized in Cluster B disorders, accounts for the origins of BPD with a theory that draws on the work of mind-brain scientists we’ve met already: Bowlby, Mahler, Winnicott, Siegel, Schore, Fonagy, and Baron-Cohen. Keep in mind that the Cluster B disorders are disorders of the attachment system, and so the deficits that lead to insecure attachment contribute to these conditions.

The caregiver of the child who develops BPD consistently puts their own need for support, comfort, and love above those of the child, often beginning in infancy. This behavior is pathological in that it exceeds, in intensity or consistency, the ordinary solipsism, coldness, or preoccupation that produce regular insecure attachment. Love and support are offered only when behavior conforms to the caregiver’s wishes—wishes that are often subconscious, but destructive nevertheless. With BPD, the caregiver’s primary wish is to keep the child “enmeshed,” psychologically fused with the caregiver.

We all need to individuate, to develop our own distinctive personalities, desires, and feelings, which might well differ from those of our caregivers and, later in life, close others. We’re an interdependent species, but we also need autonomy, an important building block of individuation, and the work of “growing up” consists largely of finding balance between closeness and individuation, dependence and independence. In BPD, the child’s drive toward autonomy in infancy and childhood—attempts at what is called “self-activation”—is punished with the withdrawal of support and love on the part of the caregiver. The adult with BPD has therefore learned to associate independence with abandonment, which means that their attempts at healthy separation from others whom they are close to, or the autonomy of such close others, brings on a sense of sadness and emptiness, even despair; this is known as “abandonment depression.” Safety consists in staying enmeshed.

Successful individuation leads to what is known as the “real self.” In addition to individuation, development in ways that are distinct and fulfilling, the real self encompasses a sense of security, a reflective capacity, and self-control, the hallmarks of secure attachment. (Of course the strength of these traits will vary among individuals while still remaining within a normal range, and insecure attachment does not indicate pathology.) Because in BPD the individual’s real self isn’t recognized or validated—the child didn’t receive adequate attunement or mirroring from the caregiver, the heart of such validation—the child fails to develop a strong ToM (to be able to mentalize). Without seeing oneself from a third-person perspective, reflected in the validation of one’s real self, one can’t take that perspective with others. Furthermore, the child develops a “false self,” one that conforms to the (often subconscious) wishes of the caregiver for the child, the retention of traits approved by the caregiver.§ People with BPD feel emotionally empty much of the time, as if their feelings are absent or unreal, which makes sense, since they learned to deny important aspects of themselves to maintain the love of the caregiver. (This is also true of those with narcissistic personality disorder.)

Another way to view this BPD dynamic is that the child, and later the adult, “splits” her idea of herself and of her caregiver into two polarized parts: good child and good caregiver on the one hand, bad child and bad caregiver on the other. The bad parts are the ones that wish to separate, either through attempts to develop a distinctive identity on the part of the child, or through rejection on the part of the caregiver, which is the consequence of such attempts. Subconsciously, autonomy is associated with the bad child part of the split, the naughty one who’ll be punished with abandonment by the bad caregiver. Defenses are built up that keep them clinging to the false self because activating the real self comes at a terrible price. (Actually, people afflicted with BPD rarely attempt to activate the real self without substantial therapeutic help because it is so difficult and painful to do so.) People with BPD learn a procedural schema that consists of the “borderline triad”: Self-activation leads to abandonment depression, which leads to defenses that prevent the activation of the real self.

People with BPD dread and fear rejection, which enrages them, and is associated with the bad, rejecting caregiver and the abandonment depression. They never got the chance to integrate autonomy and closeness into a healthy combination, the golden mean in which the two coexist, and so they either idealize or devalue people, alternating between extremes according to how they fall within this dualistic, split world. People closely associated with those with the disorder, such as spouses or children, therefore become identified with this evil-person part, and the terrible pain rejection brings, whenever they “separate,” however unreasonable that feeling might be. That’s why people with this disorder can become enraged if they feel that someone they consider close fails to display adequate devotion. They tend to be “paranoid” in the colloquial sense of the word, finding rejection and abandonment where it doesn’t exist. The person with BPD needs to be continuously fused with someone, emotionally and psychologically, as they were with the caregiver. This often takes the form of unquestioning devotion on the part of others. BPD can be thought of as anxious-ambivalent attachment on steroids.

ON THE EDGE WITH LADY SUSAN

Lady Susan, an early novella of Austen’s that’s sometimes considered a major work, features a main character whom we can diagnose with BPD, the eponymous Lady Susan herself. We can see the fear of abandonment depression driving Lady Susan through her fury at those who resist her charms. She needs not only devoted friends, but absolute disciples. But of course, she has only disciples since her devotees aren’t genuine friends in any true sense of the word. They provide adulation rather than support and understanding, and she provides nothing in return except the privilege of allowing them to worship her. Even her confidante, Mrs. Johnson, functions more as an adoring audience for Lady Susan’s exploits than as a friend.

When the novel begins, the recently widowed Lady Susan is about to visit her brother-in-law, Mr. Vernon. She’s been staying at the home of her friends the Manwarings, where she caused no end of trouble. She found Mr. Manwaring entertaining and attractive, and to the great distress of his wife, the feeling was mutual. Austen strongly hints that they had an affair (she couldn’t state this outright). Lady Susan flaunts her power over the husband in the wife’s own home, with zero empathy for how much pain this causes. Eventually, when the situation at the Manwarings becomes too hot to handle, Lady Susan decides to accept her brother-in-law Mr. Vernon’s standing invitation to visit. A beautiful woman who trades on her charm, Lady Susan never pays her own way.

Lady Susan has other motives in addition to wanting a free ride. She’s determined to make Sir Reginald de Courcy, Mrs. Vernon’s brother, fall in love with her. This is partly because she wants to remarry to secure an income. In this, she’s not so different from many other of Austen’s characters since marriage was often the only respectable way of procuring financial security for women of the middle and upper classes. Although marriages of convenience such as that of Charlotte Lucas and Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice might make those with more refined sensibilities and greater opportunities (like Elizabeth Bennet) a bit squeamish, such behavior was not usually as positively heartless and manipulative in Lady Susan’s mode. Charlotte and Mr. Collins understand the deal they’re making, and neither has unrealistic expectations.

But for Lady Susan, this pragmatic motive takes a back seat to her compulsive and constant need for homage, which she seeks in intimate, or potentially intimate, relationships—typical borderline behavior. Lady Susan primarily targets men, usually successfully, but her hunger for reassurance also prompts her to try to win over those women who aren’t competitors. In addition to her striking beauty and seductive manner, which most (heterosexual) men find irresistible, her charm is so intoxicating that even women fall for her lies. Mrs. Vernon feels this allure and has to summon her will—all of her cognitive, executive powers that tell her what Lady Susan is really like—to resist falling under Lady Susan’s spell. As she writes to her brother, Sir Reginald (who will shortly fall in love with Lady Susan), “Her address to me was so gentle, frank, and even affectionate, that if I had not known how much she has always disliked me for marrying Mr. Vernon, and that we had never met before, I should have imagined her an attached friend . . . If her manners have so great an influence on my resentful heart, you may guess how much more strongly they operate on Mr. Vernon’s generous temper.”

Attraction and power are inextricably linked in Lady Susan’s mind, so that she finds fulfillment in dominating and manipulating others through her charms; this way, she can keep people enslaved, and keep herself “safe,” immune from abandonment. She plans to seduce her brother-in-law, Sir Reginald, into marriage, while his horrified family looks on, powerless to intervene. While Lady Susan thrills to the prospect of humiliating the entire de Courcy family (Mrs. Vernon’s family of origin) by snatching the heir and his fortune, she has a special grudge against Sir Reginald, who dislikes and distrusts her—with good reason. By daring to disapprove of her in the past, he has made himself her particular target. In psychotherapeutic terms, by resisting Lady Susan, Reginald evokes the limits to her power that might lead her to face the emptiness of the abandonment depression, the emptiness that would engulf her if she ever failed in her attempts to control others.

Lady Susan’s other plan is to force her daughter, Frederica, to marry against her will. She has in mind a wealthy but ridiculous man, a fop, who actually finds Lady Susan much more attractive than her daughter. Arranged marriages, like marriages of convenience, were not unheard of in Austen’s day, but these occurred mainly within the aristocracy. It was generally thought that young people should be allowed to decide whom they would marry, within reason; a parent’s consent was still a necessary moral, if not legal, prerequisite.

Lady Susan ignores such norms. She wants to disburden herself of responsibility for the girl, thereby ridding herself of the female competition posed by a beautiful daughter, and, even more delightful, torture her daughter in the process. After all, Frederica has dared to protest against the marriage, to separate her own feelings and tastes from those of her mother. For this, for committing the “sin” of individuation, Frederica must be punished—subjugated and made to suffer.

Displaying the lack of empathy characteristic of the disorder, Lady Susan treats Frederica like an object, an object that she no longer wants to have to care for. To further her plans and prevent Frederica from finding allies, Lady Susan tells everyone that her daughter is a stubborn, worthless girl, unteachable and incorrigible. But Frederica is actually a decent, lovely young woman who’s terrified of her oppressive mother and desperate to escape a marriage she finds repugnant.

When Frederica asks Sir Reginald’s help in averting the marriage her mother has planned for her, Lady Susan’s borderline rage emerges. The domain of intimate personal relationships is precisely where she’s most likely to be triggered. Sir Reginald is sympathetic to Frederica, and Lady Susan can’t bear this challenge to her domination, which suggests the possibility that Sir Reginald isn’t completely under her sway (fused with her). She angrily confronts Sir Reginald, and she’s so obnoxious that he determines to break with her and to leave his sister’s house for the remainder of her visit. But Lady Susan soon regains her equilibrium and repairs her relationship with Sir Reginald so thoroughly that, to the horror of the rest of the Vernon and de Courcy families, they become engaged.

Lady Susan uses all her charm and strategy to repair this breach, and when she succeeds, she confesses to her friend Mrs. Johnson,

Oh how delightful it was, to watch the variations of his countenance while I spoke, to see the struggle between returning tenderness and the remains of displeasure. There is something agreeable in feelings so easily worked on. Not that I would envy him their possession, nor would for the world have such myself, but they are very convenient when one wishes to influence the passion of another.

Lady Susan’s lack of feeling, frankly and proudly admitted, suggests that empathy disorders can lead to all manner of evil, large and small. I won’t spoil the ending in case you haven’t read this wonderful novella (or seen the excellent movie that was made of it, Love & Friendship), but this indeed is Austen’s world. A gesture toward tragedies that might have been will suffice.

THE SOCIOPATH NEXT DOOR: MEET MR. ELLIOT

The second Cluster B disorder I’ll consider is called antisocial personality disorder (APD), also known as psychopathy and sociopathy. People afflicted with APD routinely disregard the feelings and violate the rights of others. They fail to conform to social norms, in many cases, by committing crimes. They can be irritable, aggressive, and impulsive, behaving with total disregard for their own safety as well as the safety of others.

APD appears to originate in early, chronic, and prolonged neglect or abuse. If we characterize it in terms of the attachment disorders, it’s an extreme case of reactive attachment disorder, the inability to attach to anyone. Not only do the afflicted fail to establish attachments to others, they are also relatively indifferent to human connection. (This isn’t true of those with BPD and NPD, who might lack empathy but care very much about their relationships.) Those with the dangerous version of APD are capable of viewing murder as a minor infraction or appropriate response to frustration. The psychiatrist Bruce D. Perry recounts asking a prisoner why he had killed two adolescent girls and raped their dead bodies. The answer, “We started talking and they invited me up to their apartment to fool around. Then when they got me up there, they changed their minds. It pissed me off.”¶

People with APD are frequently motivated by the need to dominate. Some find pleasure at seeing others suffer. But whether or not they have a taste for sadism, they display muted or absent emotional responses, especially with regard to positive, prosocial, benevolent emotions. They’re generally willing to do whatever it takes to get what they want. Treating others like objects, they ride roughshod through people’s lives.

While APD is characterized by flaws in emotion-processing systems, the disorder appears to divide into more and less controlled versions. Some people with the condition can’t contain their impulses, and they lash out at others violently and with little provocation; the dysregulatory aspects of the condition prevail in these people. People with this type of APD are often jailed for serious crimes. No one in Austen’s novels fits this profile.

Some people with APD are coldly manipulative, conning other people into giving them what they want. They might still wish to harm or dominate others, but they often, although not always, have better powers of self-regulation than their impulsive, often violent counterparts. To make matters worse, they can be charming, which makes them dangerous; it’s often difficult to know that someone has this form of APD until the damage has been done. It’s likely that different forms of APD correlate with different irregularities in brain structure and circuitry, but little is known about this at the moment.

DSM-5, doesn’t note these differences among those with the disorder, a flaw that might well be rectified in future editions of the DSM. I’m going to make the distinction by using a term was offered by the psychiatrist Hervey M. Cleckley (1903–1984), “high Machiavellians,” “high machs” for short, to describe the type of socially adept person who has the disorder. The manipulative individual with antisocial personality disorder does indeed fit the profile of the perfect politician described in Machiavelli’s The Prince, a treatise on how to succeed in politics by being strategic, devious, and deceitful. Austen’s characters with APD have the regulated, manipulative version of this syndrome. But remember, whatever form the disorder takes, whether violence or manipulation or deceit is inflicted on others, lack of empathy predominates.

Mr. Elliot in Persuasion is a high mach, as heartless as Lady Susan, but much more successful at concealing his malevolence. He is the charming cousin of Anne Elliot (the heroine); he is also heir to the Elliot title and fortune—currently possessed by Anne’s father, Sir Walter Elliot—which descends through the male line. Ten years earlier, when Anne had been away at boarding school, Mr. Elliot had been in constant touch with her family, raising hopes of a marriage between himself and Anne’s older sister, Elizabeth. He suddenly abandoned this connection without explanation. He rekindles his relationship with the family once more when he meets them at Bath, paying particular attention to Anne, whom he finds very attractive.

While Anne is gratified by her handsome cousin’s admiration, with her usual sharpness she senses that something isn’t quite right: “There was never any burst of feeling, any warmth of indignation or delight, at the evil or good of others. This, to Anne, was a decided imperfection. . . . She felt that she could so much more depend upon the sincerity of those who said a careless or a hasty thing, than of those whose presence of mind never varied, whose tongue never slipped.” Anne, who’s an exquisitely accurate judge of character, picks up on the artificial nature of Mr. Elliot’s emotional expressions. Mr. Elliot can’t leave anything to spontaneity, for he must work to produce the outward expression of feelings that he’s incapable of experiencing, feelings that come naturally to people with unimpaired emotional systems.

Anne learns the truth about Mr. Elliot’s character from her friend, Mrs. Smith, a former schoolmate who’s fallen on hard times. Mrs. Smith is in Bath to “take the waters” (bathe in the warm springs) for her declining health, but she’s so impoverished that she can barely afford the minimal medical care that she needs. Her husband has recently died, leaving her with difficult financial and legal problems, which, we learn, are principally due to Mr. Elliot’s behavior. When Mrs. Smith decides to reveal Mr. Elliot’s true character to Anne, she prefaces her information with a general description that indeed diagnoses him as a person with APD:

Mr. Elliot is a man without heart or conscience; a designing, wary, cold- blooded being, who thinks only of himself; who, for his own interest or ease, would be guilty of any cruelty, or any treachery, that could be perpetrated without risk of his general character. He has no feeling for others. Those whom he has been the chief cause of leading into ruin, he can neglect and desert without the smallest compunction. He is totally beyond the reach of any sentiment of justice or compassion.

Mrs. Smith then offers proof of the callousness of Mr. Elliot’s actions while also shedding light on his strange behavior toward Anne’s family. Mrs. Smith knows all about him because when Mr. Elliot was young and relatively poor, the Smiths generously welcomed him into their home. Mrs. Smith in fact became his confidante and supporter.

According to Mrs. Smith, Mr. Elliot’s one goal at that time was to get rich through marriage. A match with Anne’s sister Elizabeth would have satisfied his desire for status, but as the husband of Elizabeth, he would have been accountable for his whereabouts and behavior. He would have been forced to assume a respectable lifestyle far more often than suited his tastes, which tended to run toward the sordid and the low. Mrs. Smith has no information about Mr. Elliot’s recently deceased wife because she was too inferior, in relative social standing, for a woman of Mrs. Smith’s standing to associate with regularly. And Mrs. Smith is neither rich nor titled. (Alas, Austen is not above all the snobbery of her time.)

Mrs. Smith further reveals that Mr. Elliot held Anne’s entire family in contempt, proving this with a letter in which he boasts of having gotten rid of Sir Elliot and Elizabeth: “I have got rid of Sir Walter and Miss. They are gone back to Kellynch . . .” So little did he value the nobility of which Sir Walter is so proud that he boasts, “[I]f baronetcies were salable,” he would have sold his “for fifty pounds, arms and motto, name and livery included.”

In the intervening years, however, Mr. Elliot has learned to value the good things that come with a noble title, and this accounts for his wish to reestablish a connection with Anne’s branch of the family. In particular, he fears that Sir Walter (Anne’s father) will marry Mrs. Clay, a lawyer’s daughter who is pursuing him, and that this marriage might produce a boy, who would of course inherit the baronetcy and the wealth that goes with it. Mr. Elliot hopes to prevent this, so he stays close to the family to watch Mrs. Clay and find a way to thwart her schemes, should this become necessary. In addition, contrary to his usual taste in women of a lower class, he is smitten with Anne—I won’t say “in love” because he is incapable of this, but he does find her attractive. With lesser urgency than he feels to watch Sir Walter, he stays around to woo Anne.

Mrs. Smith has also matured and come to alter her values, although this has taken her in a different direction than Mr. Elliot’s. Were she to meet with attitudes like Mr. Elliot’s today, her response would be quite different from what it had been in her youth, when “they were all a gay set.” However, her wisdom has come at a price. Mr. Elliot led her late husband into ruinous financial ventures, and although he has the means to repair some of the damage by helping her to reclaim some property in the West Indies that still belongs to her, he refuses to help, ignoring her repeated requests. Mrs. Smith has hoped, with Anne’s engagement to Mr. Elliot, to have an advocate who would effect some material change in her circumstances. When she learns the truth about Anne’s feelings, she has instead a good friend who’ll listen to her troubles, and the relief of finally telling them.

DOING WHAT COMES UNNATURALLY

Mr. Elliot possesses strong powers of self-control that enable him to project a front of respectability when he encounters the Elliots in Bath. Of course, all of us on occasion encounter situations in which it’s necessary to call upon willpower in order to avoid inappropriately expressing our true thoughts; this is an important aspect of emotional regulation. But for high machs, this is a continuous process, a necessary evil, because self-control is crucial to being able to manipulate others; high machs are consummate actors.

Nevertheless, Mr. Elliot shares the fundamental dysregulation that’s a feature of his disorder, although he’s learned to keep it in check (indeed, most high machs do this). Although Mr. Elliot never loses his cool during the time he reconnects with Anne’s branch of the family (as Anne observes, nothing about him is ever impulsive), his past reveals that such powers of tightly wound restraint have not come naturally.

Mrs. Smith tells Anne that in the days when they were close, Mr. Elliot led a riotous life, succumbing thoughtlessly to his impulses and living only to fulfill his cravings of the moment. He cared nothing for the future or what anyone thought of him. Mr. Elliot’s changing values, in particular his desire to inherit the baronetcy, have given rise to different modes of behavior. He’s certainly not a better man, just one who’s learned to defer lesser gratifications in pursuit of greater ones. Perhaps his craving for domination got the better of his less sophisticated yearnings—the money and status that come with a title afford plenty of opportunities for gratification at the expense and humiliation of others.

Another talent that Mr. Elliot and all high machs acquire is the capacity for ToM, which includes being able to infer what others are feeling, despite their lack of full-blown empathy—they have cognitive but not affective empathy. In fact, their ability to manipulate others depends on a strong and accurate ToM; you can’t con someone into doing what you want if you can’t predict their behavior, and you have to be able to read thoughts and feelings in order to predict correctly. But high machs don’t develop the ability to read emotions by recognizing emotions automatically at bodily and subcortical levels and then translating them into conscious perceptions. They lack an internal reference point for reading emotions. They learn to decode emotional expression from what they know about how people behave. They learn that certain expressions lead to certain behaviors; for instance, when someone smiles at you, they’re being friendly and are more likely to grant you a favor.

This process might become more or less automatic, entering procedural memory through repeated experiences of deliberate analysis. But it would nevertheless always be an acquired talent rather than a visceral response, and therefore less consistently accurate than normal modes of reading feelings. So high machs would be liable to make mistakes in predicting others’ reactions or behavior when they failed to perceive feelings accurately.

An analogy: Think of a very well-trained blind person making his way through an unfamiliar part of town with a walking stick. He’ll rely on senses other than vision, and on the action of the cane, in order to know how to proceed. He might become very accomplished at navigating his way around, but he’ll likely still be at a disadvantage compared to a sighted person. And if he does become nearly as proficient as a sighted person, this happens through alternative senses. Ditto for our high mach, who reads emotions well most of the time.

Because Mr. Elliot lacks such intuitive knowledge of many common emotional responses, he sometimes miscalculates the effects of his behavior. For instance, he compliments Anne by observing that she’s “too modest for the world in general to be aware of half her accomplishments, and too highly accomplished for modesty to be natural in any other woman.” He insists that his observations are not mere flattery, but that he’s had a longer acquaintance with her “disposition, accomplishments, and manner” than she’s aware of. Anne realizes that they must have a mutual acquaintance and tries to get Mr. Elliot to reveal who this person is. He defers the answer to another meeting.

Anne doesn’t have long to wonder, for the next day, when Mrs. Smith realizes that Anne doesn’t have strong feelings for Mr. Elliot, she reveals that she’s the common acquaintance, and she also tells Anne the truth about his character. If Mr. Elliot had possessed any sense of how a person of integrity would react to hearing about his behavior toward the Smiths in the past, and of his neglect of Mrs. Smith’s pleas for aid in the present, he would have steered as far away from the topic of Mrs. Smith as possible. But on the contrary, by dropping hints of a common acquaintance, he invites Anne to discover the truth. He obviously doesn’t have a clue about how knowledge of his behavior would affect Anne. He lacks the social intelligence to understand that she’d feel indignation on her friend’s behalf.

While Mr. Elliot doesn’t win Anne’s heart, this isn’t because Anne discovers his true character. Marrying Anne was never his main objective. Above all, he wants to secure his inheritance, and in that area, he does triumph, diverting Mrs. Clay by running off with her himself. Given his taste for women who don’t hail from upper-class circles, he’s likely to be much happier with Mrs. Clay than he would have been with Anne anyway. The narrator suggests that Mrs. Clay might ultimately manipulate Mr. Elliot into marrying her so that she too will enjoy the perks of belonging to the elite. Not bad for a country lawyer’s daughter. Blessed with the ability to get others to give her what she wants, Mrs. Clay might indeed be the highest of the high machs in Austen’s work. Perhaps someone who writes novels based on Austen’s books will tell her story.

EMPATHY AND MORALITY: SOME CLARIFICATION

In Emma, Mr. Knightley scolds Emma for her lack of empathy, but he might just as well have blamed her for a breach of ethics or decorum. Her behavior is certainly open to criticism on these grounds. It’s not much of a stretch to say that Emma breaks the Fifth Commandment, “Honor thy father and thy mother,” since Miss Bates was one of the mother figures in Emma’s childhood, as Mr. Knightley points out. And young ladies were not supposed to insult their elders, or anyone else for that matter, especially in Emma’s public, flagrant mode. But Mr. Knightley focuses on Emma’s lack of empathy rather than her breaking of the rules, and this prompts her to do the right thing.

Austen suggests here and elsewhere that empathy is an effective and important source of morality, far more important than abstract principle. Like much of Austen’s thinking, this observation agrees with the philosophy of her near contemporary, David Hume, who argued that empathy, or sympathy as he called it, was the ground of ethical behavior. This view radically challenged prevailing notions about ethics that were central to Western civilization. Christian thought has traditionally suggested that morality stemmed from reason, the God-like quality in human nature that distinguishes us from all other animals. Secular philosophy of the Enlightenment was in accord, as was much of the literature and philosophy of the Classical world, ancient Rome and Greece (remember Plato’s charioteer from Chapter Two).

Many mind-brain scientists today agree with Hume and Austen that empathy and morality are connected. Others call the connection into question. Because empathy is such a critical aspect of social intelligence—our most thorough access to one another’s minds and hearts—it’s worth looking, if only briefly, at claims about the scope and limits of this capability.

To begin with—quite literally to begin with—empathy is the source of morality in evolutionary terms. Frans de Waal, an ethologist and psychologist whose work also addresses anthropology and philosophy, fought for decades to get this view accepted among scientists. He struggled against a dominant ideology that he calls “veneer theory.” This is the belief that humans are basically nasty and brutish, and that morality is merely a thin veneer over our despicable natures (another traditional idea, expressed eloquently by the seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes). Whatever good we have comes from our capacity for reason, our ability to formulate moral codes that enable human beings to live together without destroying one another. De Waal disagrees vigorously.

De Waal counters that morality originated with our emotions and visceral reactions—with our empathy for one another, which we see in less developed forms in other mammals: “We started out with moral sentiments and intuitions, which is also where we find the greatest continuity with other primates. Rather than having developed morality from scratch through rational reflection, we received a huge push in the rear from our background as social animals.”# De Waal readily admits that he is “a firm believer in David Hume’s position that reason is the slave of the passions.”

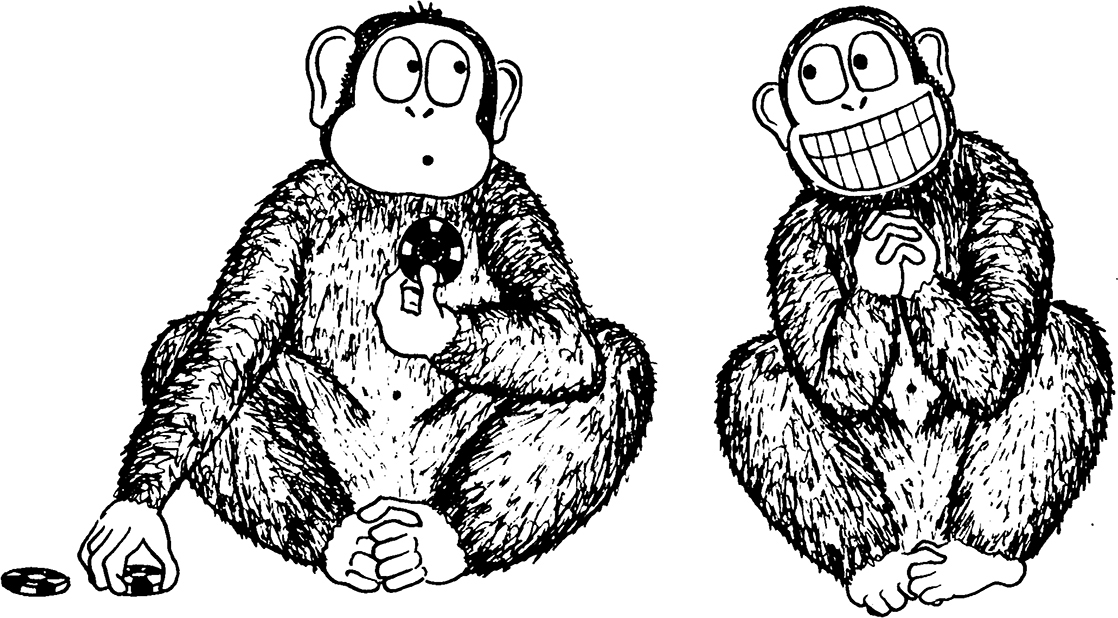

Primatologists working in the field with the great apes (including de Waal) have reported countless instances of caring, generosity, and altruism among our close cousins. But if these claims were to be taken seriously by the scientific community, they had to be shown in the lab rather than observed in the field. De Waal and his team designed an experiment that did just this, demonstrating the presence of empathy in chimpanzees.

Two chimps, Peony and Rita, were the subjects in this experiment. Peony was asked to pick from a bucket full of red and green tokens. No matter which color she chose, Peony would be rewarded with a treat. But if she picked a green token, Rita would also receive a reward. After a while, Peony began to select the green tokens two out of three times, ensuring that Rita also got rewarded.

The same behavior was seen in other chimp pairs in the same situation. But if a chimp was alone and asked to choose, she wouldn’t distinguish between the colors, choosing randomly. In addition, in the two-chimp scenario, when the chooser picked the wrong color, the deprived neighbor would often protest, hooting or begging. But intimidation wasn’t a successful strategy; it actually prompted the choosing chimp to pick the red, “selfish,” tokens. It’s hard not to think that this was spite. And dominant chimps, who had the least to fear, were the most generous. Noblesse oblige.

The chimps weren’t acting on principle, thinking that, for instance, it’s fair to share your treats, as we tell our children. Not even a chimp or bonobo is going to act for the greater good as a result of moral reasoning; they really don’t have the brainpower for that. That the chimps understood that their partners wanted rewards and were sad not to get them—that they empathized—is the only explanation that makes sense.

This experiment therefore provides strong evidence for the claim that empathy is the source of morality in evolutionary terms because chimps are near to us on the evolutionary ladder; they share ninety-eight percent of our DNA, their brains resemble our own, and they have levels of cognitive intelligence comparable to young children in many respects. I think it’s likely that chimps are able to mentalize and therefore that the fortunate chimps in the protocol understood that their neighbors felt deprived. But even in nonhuman animals who very likely can’t think at these higher levels, such as rats, emotional resonance (affective empathy) appears to lead to prosocial actions.

Another support for viewing empathy as an important building block of morality comes from the way we actually make moral choices much of the time. In day-to-day life, instances of fairness, virtue, kindness, and cooperation don’t come from abstract principles, but from feelings. Affective empathy and the desire to help have been ingrained in our nervous systems.** Charles Darwin, who believed that morality stemmed from empathy and was found in other nonhuman animals, wrote of altruism, “Such actions . . . appear to be the simple result of the greater strength of the social or maternal instincts than that of any other instinct or motive; for they are performed too instantaneously for reflection, or for pleasure or pain to be felt at the time.”†† Reason has little to do with our benevolent impulses much of the time.

When Frank Churchill rescues Harriet from the gypsies, he doesn’t stop to think of his obligation as a gentleman to rescue a damsel in distress. He just acts, impelled by feelings that are deeply bred in the bone. You can bet that Emma does charity work out of compassion that’s grounded in empathy, her understanding of, and resonance with, the sufferings of the impoverished. That’s because Emma never succeeds at anything she decides to do on principle, such as cultivating her accomplishments. Emma has to feel that something’s important, or she fails to act.

Nevertheless, for humans, doing the right thing doesn’t require empathy. We can be impelled by forces other than empathy to perform good deeds. The existence of competing, allegedly better, motives for benevolence is indeed one of the arguments against viewing empathy as a precursor to moral action. For instance, Emma might have been kind to Miss Bates because she wanted to look good in Mr. Knightley’s eyes, and so have been motivated by entirely selfish reasons. Or she might have been inspired by guilt rather than compassion, and so acted out of a sense of obligation to others that nevertheless had little to do with empathy. Or she might have wanted to behave appropriately, which meant that her kindness stemmed from the desire to conform to accepted behavior and moral codes rather than fellow feeling. Or perhaps she was guided by reason, the knowledge of right and wrong; it was wrong to insult Miss Bates and right to atone for this by effortful benevolence. These are the grounds on which Mr. Knightley does not scold Emma. Psychologist Paul Bloom argues that moral reason, the last of these alternative motives, is a much more reliable foundation for good works than empathy. And so we’re back to Enlightenment thought about morality, similar arguments to the ones Hume and Austen opposed.

Or take Mrs. Elton, who decides to connect Jane Fairfax with an excellent prospect for employment as a governess. This appears to be a benevolent, helpful project, since it’s likely that Jane will be compelled to support herself, and a job as a governess with a good family is the best that she can hope for. But Mrs. Elton isn’t motivated by empathy, and in fact it’s Mrs. Elton’s insensitivity—her lack of empathy—that prevents her from seeing that Jane doesn’t want her help. At our most generous, we might say that Mrs. Elton acts on principle, on the assumption that finding Jane a job is the right thing to do. Or that she acts out of concern for Jane. (Of course, knowing Mrs. Elton, many of us suspect that she is taking this task upon herself as a way of declaring her own importance as a patron rather than because she truly wishes to help Jane.)

Just as we can be inspired to do the right thing by motives other than empathy, a lack of empathy doesn’t always lead to cruelty, aggression, self-centeredness, or any other of the negative traits that characterize personality disorders, nor does it always lead to evil. Baron-Cohen describes those who behave in antisocial or immoral ways as possessing zero-negative empathy, but he also has another empathy disorder category, zero positive. This applies to autistic people, who often lack the ability to empathize or mentalize. Like those who have personality disorders, autistic people have severe deficits in social intelligence when compared to neurotypicals. But they don’t harm others. Empathy is one factor among many that determines a person’s moral nature and behavior.

It’s also possible to empathize and deliberately suppress or act against the feelings that arise from empathy. When Harriet comes to Emma to tell about Robert Martin’s proposal, Emma very likely empathizes with Harriet in the technical sense, apprehending Harriet’s excitement both cognitively and emotionally. But she acts against her empathy because she has other plans for Harriet. She understands Harriet’s disappointment but reasons that the better life that will follow from her schemes will ultimately compensate Harriet for any distress she feels at the moment.

A more sinister example is seen in the famous experiments in obedience to authority conducted by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s. A researcher in a white lab coat (which signals authority) instructed participants to continue to push a button that gave electric shocks to fellow participants, even though they were aware that these shocks were painful and were escalating in intensity. Most subjects were willing to do so despite the protests and suffering of their co-participants. Don’t worry about the person who received the shock; he was actually a part of Milgram’s team, and the shocks weren’t real. But do worry about a species capable of doing this. Most rhesus monkeys will refrain from pressing a lever that gives them food if the lever simultaneously shocks another monkey. They’re willing to starve to death.

Some mind-brain scientists argue that empathy can actually do more harm than good. For instance, since empathy offers a window into vulnerabilities, it can tell you how best to hurt someone. But this applies to cognitive empathy, not full-scale empathy, which includes emotional resonance; cognitive empathy means knowing about someone’s feelings rather than sharing them. But even when we act on full-fledged empathy, feeling as well as thinking from someone else’s point of view, the results can be less than admirable.

Even though empathy can inspire moral action, it is often limited in its scope. The closer we are to someone, or the more closely they resemble us, the more likely we are to empathize with them. Mr. and Mrs. Elton lack empathy for Harriet because they perceive her as belonging to the “out” group, not of their class or kind. Mr. Elton feels no compunctions about adding to her humiliation with a caustic remark when she stands alone and neglected at a ball. Racism, sexism, and all the other instances of unjust discrimination depend on this bias, on the failure of empathy to activate for people whom one group has designated as different and other.

This tendency to look out for our own also means that we often fail to empathize with, or care about, those who are distant in terms of geography as well as relationship—out of sight, out of mind, as the saying goes. We also tend to feel empathy for individuals, which makes caring about the suffering of populations, however distressed, a challenge. This is known as the “identifiable victim effect,” described by economist Thomas Schelling:

Let a six-year-old girl with brown hair need thousands of dollars for an operation that will prolong her life until Christmas, and the post office will be swamped with nickels and dimes to save her. But let it be reported that without a sales tax the hospital facilities of Massachusetts will deteriorate and cause a barely perceptible increase in preventable deaths—not many will drop a tear or reach for their checkbooks.

Fundraisers for charities understand this. Think of how many of the appeals you receive contain stories about individuals that make their plight and their humanity real to us.

As humans, we have the cognitive ability to overcome the bias in favor of our own, those who are like us or close to us. We’re capable of enlarging what philosopher Peter Singer calls “the circle of care,” the reach of the help and protection that we’re willing to give to others. We often call on reason in order to do this. This is what institutions like the United Nations and the World Court, grounded in principle, attempt to do. Legal measures such as the Geneva Conventions that guarantee humane treatment for prisoners of war, and statements like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights similarly attest to our powers of moral reasoning. But these instances of our humanity haven’t significantly decreased the inhumanity we humans display in so many places and on so many levels, usually to those who are different or outsiders. The difficulty we have in extending compassion and justice to all, even in countries where such principles are supposed to prevail, shows how hard it is to act solely on principle. Indeed, our principles often follow our feelings (reason is the slave of the passions), so that it becomes right in our minds to discriminate against—even exterminate—a given population.

Which brings us back to evil. Feeling empathy doesn’t guarantee goodness or compassion, but the absence of empathy makes it far easier to harm others. Although people sometimes act against their feelings of empathy because they believe that it’s the right thing to do, this doesn’t mean they find it easy. Far more often, people who harm others lack empathy, or turn off their empathy, in order to be able to hurt others. But even then, feelings of identification and the recognition of another person’s humanity can take place subliminally. Veterans who suffer from PTSD often feel the aftereffects of having committed atrocities alien to their natural capacity for empathy.

We can also call on empathy itself rather than moral principle to enlarge our circle of care. We’re certainly capable of feeling genuine empathy for others who are distant or different from us, although we often fail to do so. As with all empathy, this requires paying attention—really thinking, for instance, about the distress of those others, even if their identities differ from our own and even if they’re halfway around the world.

Many mind-brain scientists agree that empathy is connected to morality even if it isn’t an absolute precondition for it, nor a guarantee that those who empathize will do the right thing. This view matches with what we see throughout Austen’s work. Austen’s claims for the value of empathy aren’t quite as strong as Hume’s; they’re closer to Baron-Cohen’s thinking. Her point isn’t that empathy necessarily leads to good works—although this is frequently the case in her novels—but rather that an absence of empathy enables a person to hurt others. Just as important, if you’re going to act in ways that benefit or help someone else, you must be able to take their perspective, at least to some degree. In Austen’s view, empathy might not be a panacea for the selfishness and callousness that we’re all too prone to as a species, but it’s nevertheless at the moral center of our lives.

Our mind-brains evolved when we lived in small groups, and they’re still meant to function in that kind of environment. In the small hunter-gatherer communities that survive today, human nature appears to much greater advantage. Empathy and care are abundant, and people live good, although simple, lives. Almost everyone contributes to the survival and well-being of the community. But this isn’t difficult in a group in which everyone more or less knows everyone else.

In Austen’s novels, where characters inhabit a world with private property and hierarchies of status and power, a world that was quickly becoming our own, people generally create their circles of care by opting out of the competition for wealth and glory. Austen’s heroines and heroes are fortunate enough to be able to do so, and they do as much good as they can within the reach of their influence. Some readers view this as a depressing retreat from responsibility, a refusal to work on the structural problems generating injustice and poverty.Mr. Knightley might ensure the well-being of his parish poor, but without structural solutions to poverty, such well-being is only guaranteed for his lifetime.

While I wouldn’t be as judgmental about Austen as some, they’re right that we do need solutions that don’t depend on the kindness of strangers. But these solutions are hard to come by because global caring of the kind needed in large societies is extremely difficult for our species to embrace, as we clearly see from the world news. Empathy might be a poor foundation for moral action, but I’m not convinced that we are, on the whole, capable of a better one.

One problem might well be that the people who tend to rise to power aren’t interested in extending our circles of care. Austen certainly thought this the case, which is why a retreat from the larger world appears to her to be a good option for her characters. She likely agreed with Voltaire, who wrote: “We must cultivate our garden.” This is the moral of Candide, which Austen is sure to have read. What this means in the context of Voltaire’s novel is that the world is a terrible place where horrendous things happen and where the least ethical people are in charge. The best we can do is retreat to our own spheres of caring and action and do the good we can do at this local level.

Even so, while Austen showed that a retreat from the world was a good option for her characters, she didn’t mean to suggest they should disengage from civic duties. We don’t see the public lives of her male characters, but as noblemen (Darcy), clergymen (Edmund), and landed gentry (Mr. Knightley), they certainly participate in public affairs. And while her couples live in the country, far from the poverty-stricken slums of London and the rising industrial towns of the north, their surrounding communities provide opportunities for helping others. Mr. Knightley helps and advises the farmer, Robert Martin, and Emma tends to the poor. This is personal help rather than societal change, but if Robert Martin does well, his family will be financially secure and perhaps even upwardly mobile; there’s a famous saying that it takes three generations to make a gentleman. Living in the country might afford a more sheltered life, but it doesn’t necessarily mean sticking your head in the sand. In Austen’s view, if you’re going to build a better world with better values, you have to start small, and at home, with families and communities. People need to think locally, and maybe, if we’re lucky, we’ll eventually act responsibly, ethically, and globally.

* Siegel, The Developing Mind, 176.

† Simon Baron-Cohen, The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty, (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 28.

‡ Simon Baron-Cohen, The Science of Evil, 75.

§ D. W. Winnicott invented the terms real self and false self, which are widely used in psychotherapeutic theory.

¶ Bruce D. Perry, The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 103.

# Frans de Waal, The Bonobo and the Atheist (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013), 17.

** Dacher Keltner, Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 50.

†† Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man (New York: Penguin, 2004), 134.