At first glance, Sense and Sensibility appears to set up a clear-cut opposition between reason and feeling through the two sisters who personify these traits: Elinor is sense (reason) and Marianne is sensibility (feeling). But we soon begin to see that this split doesn’t do justice to Austen’s novel: Her heroines are far too complex to personify qualities in this simplistic fashion. Elinor might appear to think more rationally than Marianne, and Marianne to feel more deeply than Elinor—at least in the opening chapters—but Sense and Sensibility ultimately shows that feeling and judgment are inseparable.

Austen sets up an apparent opposition only to undermine it (or deconstruct it, as literary critics like to say). To begin with, she knew she could depend on readers in her day to recognize the shakiness of the dichotomy between thought and feeling from the very title of the novel, an advantage we’ve lost. Austen’s readers would have known that the words sense and sensibility have additional meanings that don’t fall into neat and opposite categories. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, both words mean perception in a simple sense, the capacity to take in what’s around you. Let’s say you’re at a ball. You can sense, or be sensible of, the conversations of your neighbors.

But this isn’t the only way in which the meanings morph into one another. Sense is also defined as emotional consciousness, “a glad or sorrowful, grateful or resentful recognition of another person’s conduct, an event, a fact or a condition of things.” For instance, Elinor has the sense [feeling] that Lucy, her rival for Edward’s love, dislikes her as soon as they meet, even though she doesn’t yet know about Lucy’s secret engagement with Edward. So sense, like sensibility, can refer to feeling. And the adjective for both words is sensible, which means both “capable of . . . emotion (feeling)” and “endowed with good sense; intelligent, reasonable, judicious.” Being sensible can therefore mean possessing either reason or feeling. Sensibility is even, depending on how it is used, listed as a synonym for sense! Here’s a sentence no self-respecting author should write, but it illustrates my point: Although Elinor is sensible of Lucy’s dislike, and sensible enough to be disturbed by it, she’s sufficiently sensible to behave as if they’re the best of friends.

Although Austen’s readers might have been more likely to catch on to this ambiguity of meaning than we are today, we don’t need to rely on a dictionary to see that neither sister embodies pure reason or pure feeling. Elinor appears to be the poster girl for good judgment, but it’s a mistake to think she’s guided by reason alone, or that she lacks passion. To begin with, if she appears to lack feeling (especially in Marianne’s view), it’s only because she does not outwardly express what she feels, not because she’s apathetic; she has superior powers of emotional regulation, or “self-control,” as they called it in Austen’s day. And although the excitable Marianne interprets such outward calm as indicating a lack of feeling, this is certainly not the case.

We see this in Elinor’s relationship with Edward, the man she loves. Elinor had first begun to see Edward regularly at her great-uncle’s estate, Norland, before Elinor’s family was forced to move. Norland had been destined to be inherited by Elinor’s father from an elderly and childless uncle. Elinor’s family had lived with this relative, providing care and companionship in his declining years. Elinor’s father dies a year after inheriting the estate from his uncle, and left the estate to John, Elinor’s half-brother from her father’s previous marriage. This stepbrother is married to Edward’s sister, Fanny. Elinor and her mother and sisters must therefore move from Norland, which they do after a few months of looking for a new home. In the interim, at Norland, Elinor and Edward get to know one another.

In those months while the family was still at Norwood, Edward was a frequent visitor and appeared to be warmly attached to Elinor, although he didn’t propose. But when he later visits the family at their new home in Devonshire, his manner is strangely altered. Edward is often moody and distant, although occasionally he’s more like his old self. His treatment of Elinor reflects profound ambivalence: “the reservedness of his manner towards her contradicted one moment what a more animated look had intimated the preceding one.”

But despite his “coldness and reserve,” which leave Elinor “vexed and half angry,” she resolves “to regulate her behavior to him by the past rather than the present,” and she avoids “every appearance of resentment or displeasure.” When Edward leaves, Elinor parts calmly from him, deliberately suppressing the display of the very real anguish she feels. Nevertheless, at the very moment that Elinor is heroically struggling to contain her emotions, Marianne “blushed to acknowledge” her sister’s lack of distress, interpreting self-control as lack of feeling.

In addition to attributing Elinor’s even temper to an unrefined callousness, Marianne also thinks that Elinor disguises the emotions she does feel out of obedience to society’s “commonplace and mistaken notions” governing behavior. In Marianne’s view, this is another instance of the triumph of reason over feeling, of allowing cold judgment and assessment of a situation to prevail over the spontaneous expression of emotion.

It would have been right in line with ideas of propriety for Elinor to refrain from showing her feelings of distress at parting from Edward. After all, there’s been no engagement between them, and so conveying stronger emotions than she would have done at the parting of any other relative would have been inappropriate. A woman wasn’t supposed to show her feelings for a man before he had actually proposed. But the struggle that Elinor clearly undergoes to contain her feelings is not motivated by knowledge of proper conduct, even though her behavior is socially appropriate. Paradoxically, it is feeling—her concern for Edgar—rather than judgment that drives Elinor to mask her suffering.

By the end of the visit, Elinor realizes that Edward is “melancholy.” Had she been distant or cross, or behaved in any way that expressed disappointment or disapproval, she would have added to his pain. Some readers might think that a cold shoulder would have served Edward right for behaving badly—leading Elinor on and pushing her away—even if he did so inadvertently. But Elinor wouldn’t agree with them.

Indeed, Elinor consistently exerts self-control to protect others, sometimes at her own expense. Feeling rather than decorum again motivates her restrained affect with her family. Edward’s “desponding turn of mind” affects Elinor deeply, and it requires “some trouble and time to subdue,” but this is exactly what she does. She contains her distress because she doesn’t want her mother and sisters to be upset on her behalf.

Just as Elinor’s sense can’t be separated from her sensibility, the reverse is true for Marianne: A cognitive, intellectual motive contributes to her habit of responding with quick and strong feeling. This isn’t to deny that the sisters are temperamentally distinct, Elinor calm and self-possessed, Marianne skittish and reactive. But Marianne’s exquisite sensitivity is also a matter of principle.

In Austen’s day, many well-known rules regulated conduct, especially for young ladies; I’ve mentioned one such rule already, that a young lady wasn’t supposed to express her love unless the man she fancied had proposed. Additionally, unmarried women and men weren’t supposed to go out together unchaperoned, exchange personal gifts, or write personal letters to one another. Such rules were often published in books that sold very well, a genre known as the “conduct book,” which offered a range of advice from dictating behavior in specific social interactions to making life-changing decisions. You can think of these guides as the self-help books of Austen’s day.

Marianne finds such entrenched notions of decorum ridiculous, contrary to the goodwill and authenticity of feeling that should ground our close relationships. As the narrator tells us, “[T]o aim at the restraint of sentiments which were not in themselves illaudable, appeared to her not merely an unnecessary effort, but a disgraceful subjection of reason to commonplace and mistaken notions.” And so, in Marianne’s view, it’s unreasonable to behave in ways that her society mistakenly deems reasonable. She thinks it wrong not to express laudable feelings, such as an innocent first love, to their fullest—to “drink life to the lees” as the poet Alfred Tennyson would later write; he wasn’t yet born when this novel was written, but he certainly inherited much of the romantic sensibility expressed by Marianne. Perhaps you’ve known a teenager or two who similarly rebels because she thinks the benighted older generation has invented rules that are stupid, superfluous, and hypocritical. This particular cultural pattern appears to die hard!

Marianne lives by her credo, as we see in experiences that parallel those of her sister. Marianne first meets Willoughby when out on a walk with her sisters. She twists her ankle and he comes to the rescue, carrying her home and, in the process, “sweeping her off her feet” as we say, both literally and figuratively. This begins a whirlwind romance in which neither Marianne nor Willoughby restrains their feelings.

Marianne blatantly disregards the conventions that Elinor respects and observes. She lets Willoughby know how she feels, although he hasn’t proposed or expressed serious intentions. She goes on outings alone with him, gives him a lock of her hair, and enters into a personal correspondence with him, all forbidden behaviors. This last convinces Elinor that Marianne and Willoughby must have entered into a secret engagement, although she’s wrong about this. Marianne writes to Willoughby although there’s been no formal engagement, assuming that their love doesn’t need official sanctions, that such guarantees of devotion are beside the point when love is genuine.

Unlike Elinor, Marianne fails to realize that following the rules of conduct and avoiding impulsivity—all the attributes of good sense—can protect against some very unpleasant if not downright dangerous experiences. Society’s rules might have restricted freedom in ways that we, as well as Marianne, find silly and unacceptable, but they also protected people, especially women. Women who spent time alone with men, as did Marianne, would be vulnerable to seduction or rape, an event that would banish them from polite society forever. Since Willoughby has already seduced and abandoned one young one woman (Marianne doesn’t know this), Marianne might have been lucky to get away with just a broken heart and her reputation intact.

Marianne also fails to think of how her behavior might affect others. When Willoughby takes a sudden leave of the family (paralleling the end of Edward’s visit), Marianne’s method of coping contrasts glaringly with Elinor’s. She gives way to “violent sorrow . . . feeding and encouraging it as a duty.” Far from trying to spare her family pain on her account, she lets everyone know she’s miserable:

They saw nothing of Marianne till dinner time, when she entered the room and took her place at the table without saying a word. Her eyes were red and swollen; and it seemed as if her tears were even then restrained with difficulty. She avoided the looks of them all, could neither eat nor speak, and after some time, on her mother’s silently pressing her hand with tender compassion, her small degree of fortitude was quite overcome, she burst into tears and left the room.

Despite her constant, “in your face” expression of feelings, Marianne’s behavior contains a strong element of decision: “She was without any power, because she was without any desire of command over herself.” Austen gets right at the truth here. Marianne succumbs to her feelings so entirely because she doesn’t want to control them, believing such control is misguided and hypocritical. Although her feelings are genuine, her extreme sensibility is to some degree a matter of principle, of judgment rather than feeling.

Both sisters possess sense and sensibility; these can’t be separated etymologically or psychologically. Austen understood that feelings are influenced by beliefs, and, even more important, no matter how much sense a person appears to possess, it’s never free from the influence of sensibility. Nor should it be, because both virtue and sound judgment depend on feeling.

SLAVES OF OUR PASSIONS

Austen’s ideas about feelings likely owed much to the philosopher David Hume (1711–1776), a near contemporary—he died the year after she was born. His works were in her father’s library, and Austen was a prodigious reader. She wrote a parody of Hume’s History of England when she was fifteen, so we know that she was familiar with at least some of his writings. Although we don’t have proof that she read Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature (published 1739–40), its fundamental ideas about feeling permeate her novels.

To begin with, Hume believed that emotion, not reason, is the source of virtue; we treat others well because we can take their perspective and feel what they feel—in short, virtue depends on empathy. Sense and Sensibility (as well as Austen’s other novels) might well have been written to illustrate this insight. All of Elinor’s behavior involves such perspective taking, an understanding of how her actions will impact others emotionally. Conversely, for all her emphasis on feeling, Marianne fails to take the feelings of others into consideration. This lapse is what she most regrets, what she realizes has been her most serious moral defect, when she gains new insight after a serious illness. She tells Elinor, “I saw in my own behavior [since meeting Willoughby] nothing but a series of imprudence towards myself, and want of kindness to others.” [my italics]

Hume wasn’t the first philosopher in the Western world to associate feeling with virtue, although he gives the point unprecedented emphasis. His truly revolutionary innovation was to suggest that emotions, or “the passions” as they were called, are inseparable from reason, and that thoughts that appear to be the product of pure reason rely on emotional input. He captured both points in a catchy statement: “Reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions.” Reason ought to be the slave of the passions because virtue, and all our best impulses, are born of feeling rather than calculation. And reason is the slave of the passions because our supposedly reasonable choices are guided by emotion. Pure reason doesn’t exist, at least not in a social or moral context.

By arguing that the passions are an inevitable part of all thought, including reason, Hume marked himself as a renegade, although like many renegades, he’s been proved right. By the time Hume entered the discussion, Western philosophy had had a long tradition of seeing reason and feeling as separate and opposed. A famous classic example is Plato’s allegory of the charioteer in his dialogue Phaedrus (c. 370 B.C.E.). Plato represents the human mind as a chariot. The driver, or charioteer, represents reason, and his chariot is pulled by two horses. One horse symbolizes moral feelings, the feelings that lead us to perform just and benevolent actions. Here Plato and Hume agree that positive actions have their source in feeling. The other horse symbolizes what Freud called the id, the primitive emotions and desires, including those of the flesh, that lead us astray and that need to be managed for a society to function. The charioteer controls both horses, ensuring that the chariot goes only in directions that he approves.

Plato is right in believing that emotion needs to be regulated, guided in the right direction if we’re to live together in ordered societies. But he’s wrong in thinking that reason, the charioteer, can do the trick. Every one of our supposedly reasonable thoughts or actions or decisions that takes place in a social context—and so most of our cognitive activity—has an emotional component. This means that the thought processes we use in most of our reasoning don’t stem from pure reason, and that feeling is woven into the very fabric of our calculations, as we see in the case of Elinor’s good sense.

In fact, the only kind of reason that can be exercised without emotional input involves asocial, neutral instances of thought, such as solving quadratic equations, something that isn’t inherently tied in with dealing with other people. But this isn’t the type of thinking that preoccupies Plato or most other philosophers. They’re concerned with the exercise of reason in our dealings with one another, in the wisdom that enables us to behave in ways that benefit societies as well as individuals. If the charioteer can’t prevent the wayward horse from running amok, he is likely to hurt or kill all the innocent people in his path, as well as himself.

The mind-brain sciences have confirmed Hume’s (and Austen’s) insight: “Reason is and ought to be the slave of the passions.” Neuroscientist Elizabeth Phelps observes that the more we learn about emotional processing, the more widespread we find its influence to be. Even those instances you might think of as “pure reason,” such as our hypothetical math problem, might well turn out to have an emotional component. Perhaps solving an equation will get you a good grade on a test and put you in the running for a scholarship. In that case, no longer is your math problem emotionally or socially neutral. Plato’s charioteer is driving toward a dead end.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio and his research team confirmed the extraordinary scope of emotion, demonstrating that thought processes that we tend to attribute to reason are firmly grounded in feeling; they depend on input from emotion-processing areas of the brain. Among their groundbreaking discoveries, they found that good judgment often relies on a healthy dose of fear. Remember that emotions help us to avoid punishers, that this is a crucial part of their function, and so it’s not surprising that judgment should rely on fear—or surprising only because Anglo-European culture has idolized reason for so long.

The connection between fear and judgment was seen in a research subject, dubbed S.M. This woman has a rare condition, Urbach-Wiethe disease, which destroys the amygdala, the part of the brain that generates fear and other related feelings such as anxiety and apprehension. By the time Damasio encountered S.M., her amygdala was totally nonfunctional.*

Damasio found that although S.M. was competent cognitively and was able to process emotions other than fear in a normal manner, she had an obvious fear deficit. She couldn’t recognize fearful faces, nor could she draw them, although she could easily recognize and draw faces with other emotions. This meant that her capacity to read social signals was also impaired. S.M. could be trained to recognize fear by being instructed on what to look for in a person’s face, especially around the eyes. But this involved a cognitive override of her automatic emotional responses: S.M. didn’t feel fear involuntarily and unconsciously in the usual way. Subsequent experiments throughout the years have confirmed that others with similar amygdala damage also have a fear deficit.

S.M.’s personal life had shown the danger of living fearlessly. She made friends and got involved romantically rather easily, but she’d been repeatedly betrayed by people she trusted. She simply lacked the feelings that would alert her to warning signs, or tell her to be careful—to avoid punishers. S.M. had been threatened with deadly weapons in more than one mugging (she couldn’t detect situations that might be dangerous) and was nearly killed by a domestic partner, yet she remained fearless throughout these traumatic events. Memories of encounters that had turned out badly also failed to engender fear, so she lacked the possibility of learning from past experiences. Since one function of the amygdala is to tag experiences with emotional value, this deficit might have been the result of the loss of two of its functions.

The old saying, “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread” might have been written to describe S.M. Although no one’s fool in many respects, her decisions were often reckless because they put her at grave risk. This proverb, which asserts the link between fear and wisdom, also shows that popular culture had bucked the tide of pure reason long before the advent of neuroscience, along with exceptions in the world of letters, such as Hume and Austen.

We see how fear enters into good judgment in Elinor’s handling of her friendship with Lucy Steele, who’s secretly engaged to Edward. Several years before Edward and Elinor met, he had been a student of Lucy’s uncle, Mr. Pratt, with whom he boarded. Lucy was then a frequent visitor at her uncle’s house. After an acquaintance of several years, they entered into a secret engagement, an action that Edward has lived to regret, especially since meeting Elinor.

Lucy realizes that Edward wants to break the engagement (he’s too honorable to do so), and also guesses his attraction to Elinor. Just before they cross paths in London, Lucy had recently shared her secret engagement with Elinor at the Middleton’s house in Devonshire. She claims to want to confide in Elinor because she trusts and respects her new friend. But she really wants to warn her away from Edward and to torment her for so obviously being the woman he’d rather marry.

Hearing Lucy’s news about the secret engagement, Elinor is dumbfounded: “[H]er astonishment at what she heard was at first too great for words.” For despite her “composure of voice,” she experiences “emotion and distress beyond any thing she had ever felt before. She was mortified, shocked, confounded.” Although there’s nothing she can do about the engagement, she quickly apprehends another danger that can be averted: letting Lucy know how deeply she’s affected.

Elinor’s payoff for her self-control is that she deprives Lucy of her triumph, and so averts the negative feelings she would have experienced in seeing Lucy gloat. Elinor dodges that punisher! She finds great comfort in “convincing Lucy that her heart was unwounded.” Elinor can’t lessen the loss and disappointment she feels, but she can—and does—protect herself from having salt rubbed in her wounds.

Elinor’s good judgment, Marianne’s poor judgment, and S.M.’s deficits fall under the category of social intelligence (or lack thereof). While most of us wouldn’t use the word social to describe S.M.’s beatings and muggings, they were technically social in that they involved dealings with other people. This is the context in which Damasio studied S.M.’s deficits. Damasio is a very philosophically minded neuroscientist, profoundly influenced by the seventeenth-century philosopher Spinoza (another renegade proved right in many respects), so it’s not surprising that he had a humanistic focus in studying S.M.’s condition. Indeed, novelists and philosophers, including Austen, Hume, and pretty much anyone else writing about the human condition, tend to consider judgment and ethics in the context of relationships, whether this concerns a relationship between two people, the workings of an agency or institution, the social structure within a society at large, or a personal connection with God.

This focus makes sense because sociality is the most important factor in brain function and development, at an individual and an evolutionary level. In fact, many scientists believe that our extreme sociality led not only to social intelligence, but to all the other intelligences we take pride in as a species. It would make sense that emotions, the very foundation of relationships, are most important in the context of social situations, in our interactions with one another at all levels.

In this respect, there’s been an interesting development that sheds additional light on the social brain as well as on Damasio’s work. It appears that the brain might indeed distinguish between social situations and other contexts, such as that neutral quadratic equation (which is rarely entirely neutral in the end). In an experiment in which S.M. and others with her condition were deprived of oxygen, they all reported feeling not only fear but panic. This suggests that the brain makes an important distinction between threats coming from the external environment, and purely internal events, such as being unable to breathe. Many threats from the external environment come from our interactions with others; certainly, this was true for S.M. Amygdala damage might be necessary to the experience of fear only when the threat comes from outside ourselves, a qualification that applies to our interactions with others much of the time.

WEIGHING PROS AND CONS, OR THE “WO/MAN OF REASON” IS REALLY “THE WO/MAN OF FEELING”

Willoughby has to decide. He must choose between staying faithful to Marianne, whom he genuinely loves, or marrying the heiress Miss Grey for her fortune. Although Austen doesn’t follow Willoughby in the throes of his decision making, he later tells of his struggle in his genuine, heartfelt confession and apology for abandoning Marianne, pledged to Elinor toward the end of the novel. As Marianne lies dangerously ill, Willoughby comes to see Elinor. He asks her to tell Marianne that he really loved her—and still does—and that he made a cruel and terrible mistake that he’ll regret until the end of his days.

And it gets worse. His behavior has added insult to injury; his heartless mode of ending the relationship exacerbated the effects of his decision. After Willoughby had abruptly left Devonshire, he stopped writing to Marianne, although she remained a faithful correspondent. When they both ended up in London for a prolonged stay, Willoughby continued to keep his distance. Finally, he snubbed her very publicly at a ball they both attended, greeting her coldly as a casual acquaintance, and not the woman he passionately adores.

In response to Marianne’s desperate notes asking him to account for his behavior, Willoughby writes a devastating letter denying that they’d ever had a close relationship or felt anything special for one another. After this, Marianne descends into a deep depression that almost costs her life. We know that stress can negatively affect the immune system; Marianne adds to this with a total neglect of her own health and safety, a common behavioral trait of those suffering from depression.

Marianne’s depression leads to the fever that nearly kills her, contracted at the home of a friend on the way back to Devonshire. It’s while she hovers between life and death that Willoughby comes to see Elinor. He explains the motives for his behavior. His aunt, who had planned to leave him her money, discovered that he had seduced and abandoned a young woman and disinherited him as a result. Willoughby was left with only one option for an income (or, at least, one option for someone who isn’t willing to work for a living): He had to marry for money. And so he engaged himself to Miss Grey and her fortune. It is she who insisted on his cold treatment of Marianne, and who dictated the cruel letter that sent her plummeting into despair.

Many people in Austen’s day would have characterized Willoughby’s conflict, between marrying for love and marrying for money, as a matter of feeling vs. reason. It was a common dilemma at the time, more for women than men because marriage was the only respectable source of income for women of the middle and upper classes. For men and women, marrying for money or status was seen as practical, leading to solid, predictable benefits, while marrying for love, without a comfortable income, was frowned upon as a choice that could get you into a bad scrape. We can all dream of “love in a cottage,” but a large house would be much more comfortable. It’s as true today as it was in Austen’s time that not having sufficient income can stress a relationship. Many would say, even today, that Willoughby made a reasonable choice.

But Austen makes sure we don’t see things that way, in terms of a stark opposition between reason and feeling—not here or in any of her novels. In her view, the marriage choice, as well as every other decision we make, relies on our feelings, and not our powers of reason. “Reason is and ought to be the slave of the passions.”

Feelings enable us to make decisions by prioritizing what’s important to us. Willoughby’s decision hinges on figuring out what matters most, and in the end, his concern for his own comfort wins out over his love for Marianne. He doesn’t make a reasoned choice; rather, one desire conquers another. He tells Elinor,

My affection for Marianne, my thorough conviction of her attachment to me—it was all insufficient to outweigh that dread of poverty, or get the better of those false ideas of the necessity of riches, which I was naturally inclined to feel, and expensive society had increased. I had reason to believe myself secure of my present wife, if I chose to address her, and I persuaded myself to think that nothing else in common prudence remained for me to do.

Although Willoughby thoroughly regrets his decision—he regretted it even in the course of deciding—he ultimately prioritizes money over love. His statement gets at the truth of how we make decisions. We might consider our choices as conflicts between reason and feeling, but they’re really conflicts between one kind of feeling and another. Willoughby knows that his reasonable choice, his action done “in common prudence,” stemmed from feelings, from his fear of being poor and his desire for the good life.

It is no accident that the word rationalize, which usually means to find reasons to justify one’s thoughts or behavior, comes from the Latin word ratio, which means reason. Rationalization, in this etymological sense, follows the usual order of things in our brains: First we decide, based on feeling, and then we explain why our decisions make sense. As Austen’s narrator says in Persuasion, “How quick come the reasons for approving what we like!” (Incidentally, rationalize is another word like sense and sensibility, which has competing and opposite meanings. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, rationalize can mean “To explain or justify [one’s behaviour or attitude] to oneself or others with plausible but specious reasons, usually unwittingly,” but it can also mean “To think rationally.” Our very language captures the entanglement of feeling and reason.)

We can look to Damasio’s work once again for neurological confirmation of this view of our behavior. By studying another research subject who, like S.M., suffered from brain damage, Damasio was able to chart many of the brain areas involved in making decisions. Not surprisingly, these were emotion-processing areas. Another check to pure reason.

This patient, whom Damasio calls Elliot, was a corporate executive who was referred to him for an evaluation after having been denied disability benefits. Elliot had suffered from a tumor in the lining of his brain that had been removed, along with cortical tissue that had been damaged by its growth. After recovering from the operation, he appeared to be cured, and he returned to work.

But all was not well. Elliot couldn’t get tasks done or manage his time. If he had to sort through documents in order to choose the ones that were needed for a given business transaction, he would get endlessly distracted by irrelevant details, or turn to another task. He was fired from his job and then from several subsequent jobs. He engaged in different business ventures until he’d lost all his money. His wife divorced him. A second marriage also ended in divorce. This man was obviously not fully functional.

Yet a battery of tests confirmed that Elliot was cognitively intact. He even placed above average on intelligence tests and other measures of reasoning ability. How could this be the case when he had cognitive deficits so extreme that he couldn’t hold a job? Although Elliot’s ability to think had seemingly been unaffected by his medical condition, what did emerge from testing, and from Elliot’s own perceptions, is that his ability to feel had been greatly diminished. For instance, he could view videos of all kinds of distressing events apathetically, lacking not only empathy, but even horror or disgust or fear or any of the other feelings we tend to have on witnessing danger or disaster. He knew that he’d been able to respond emotionally before the surgery. This lack of feeling was the key to Elliot’s cognitive deficits. He had lost access to the feelings that enable us to prioritize tasks.

You might think that Elliot could have decided rationally which of his business accounts deserved attention without input from his emotions. He could have calculated which accounts promised to pay the most, or were due earliest. And had this decision been completely devoid of social content, a pure math problem with no strings attached, he might not have fared so poorly. But he couldn’t do this because the very impetus to apply logical reasoning comes from the emotion centers that had been damaged in Elliot’s brain.

Lacking in all of Elliot’s choices was a sense of urgency, that mixture of fear and desire that keeps most of us focused on what we have to do or on what’s in our best interests. Working on an account that was due earliest might have been the logical choice, even to Elliot, but without a sense of urgency, this deduction would lack the punch of true motivation needed to keep him on track.

It’s not surprising that Elliot was easily distracted. Sitting here at the moment and writing this book, I have access to hundreds of websites. Were I to google “research on the emotions,” I could spend all day going from site to site, article to article. But my sense of urgency—definitely fear and desire in my case—keeps me focused on my writing. I want people to read my book, which means I have to write it first. I’m afraid that if I fail to concentrate, I won’t finish.

Elliot’s amygdala was intact, so unlike S.M., lack of fear didn’t account for his deficits. Rather, a different area, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) was involved in Elliot’s damaged capacities. Damasio concluded that Elliot’s inability to decide or prioritize and his deadened capacity for feeling had resulted from the removal of ventromedial prefrontal cortical areas, which included the OFC.

The OFC forms part of the underbelly of the cortex, the crinkly outermost area of the brain, which contains our most advanced processing areas and which wraps around other structures in the interior of the brain. Since the OFC is on the inside of this outer wrapping, it also borders on some of the brain’s interior areas, in particular the limbic system, which is largely responsible for generating emotion (the amygdala is part of this system). The OFC is therefore perched between cortical areas responsible for thought, and limbic structures involved in emotion. One of its functions is to coordinate information-logic areas with emotional input; the OFC would allow Elliot to realize the importance of factual information, such as “that account is due soon.”

Just as important, the OFC enables us to interpret emotional information, which includes the ability to read social signals and to form expectations about the behavior of others. It enables us to predict the rewards and punishers that follow from our behavior. And it regulates emotion (as you’ll shortly see in more detail), which helps us to control impulses. A deficit in any one of these areas would have impaired Elliot’s ability to choose wisely.

Without these abilities, Elliot was oblivious to how his actions impacted his clients as well as to the effect his behavior would have on those who evaluated his performance—not to mention his wives. He could neither perceive nor predict the disapproval evoked by his erratic, irrational behavior. And so he lost job after job and marriage after marriage. Along with his inability to feel the urgency of current tasks, he was also unable to ignore the distraction of new ones, and so he frequently gave in to the impulse to change his focus. In short, without the capacity to process and pool information normatively, Elliot was forced to make decisions with minimal emotional guidance. Pure reason equated to poor judgment.

THE BRAKING POINT

There are a few instances in which reason and emotion are pitted against one another, mainly in states of emergency. When we’re angry or upset or fearful, or in the grip of any very strong emotion, most of us find it difficult to think clearly. How often we come up with the perfect comeback long after the argument is over!

The reverse is also true: If, when upset, you can get yourself to stop and think, you’ll probably calm down to some degree. We can see this inverse relationship between reason and feeling in Elinor’s reaction when Lucy tells her about her engagement to Edward: “Her astonishment at what she heard was at first too great for words.” Emotion runs high, and so cognition shuts down. It’s only as she focuses on what she has to do to maintain the conversation in a way that protects herself that Elinor is able to answer, “forcing herself to speak, and to speak cautiously.”

Along with reason, the other capacity that shuts down with strong negative emotion is social engagement, the set of various feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that enables us to interact with one another in positive ways. This is, in a sense, self-evident: If you’re furious with someone, or in the grip of any strong negative emotion, you’re not going to be particularly receptive to what they have to say, or to be socially adept. You’re certainly not going to be in the mood to socialize or chitchat when you’re in a rage. Elinor must force herself to answer Lucy. But she momentarily loses her ability to speak, among the most social of our capabilities, and certainly necessary if she is to deprive Lucy of her triumph.

Another and more extended instance of social withdrawal can be seen in depression, as in Marianne’s situation. Devastated by Willoughby’s rejection, she becomes incapable of honoring the most basic niceties of social life. This would have meant more, and been more noticeable, in Austen’s day than our own because women had defined social duties that they were expected to fulfill. If someone called and left a calling card, as was the custom, you were obliged to return the visit, unless you wanted to deliberately “cut” someone.

When Marianne emerges from her depression, she regrets her social ineptitude: “Whenever I looked towards the past [the time she was depressed], I saw some duty neglected, or some failing indulged. Everybody seemed injured by me. The kindness, the unceasing kindness of Mrs. Jennings, I had repaid with ungrateful contempt. To the Middletons, the Palmers, the Steeles, to every common acquaintance even, I had been insolent and unjust.” Even so, the people around Marianne who care about her recognize that she’s in deep distress and respond with compassion rather than blame.

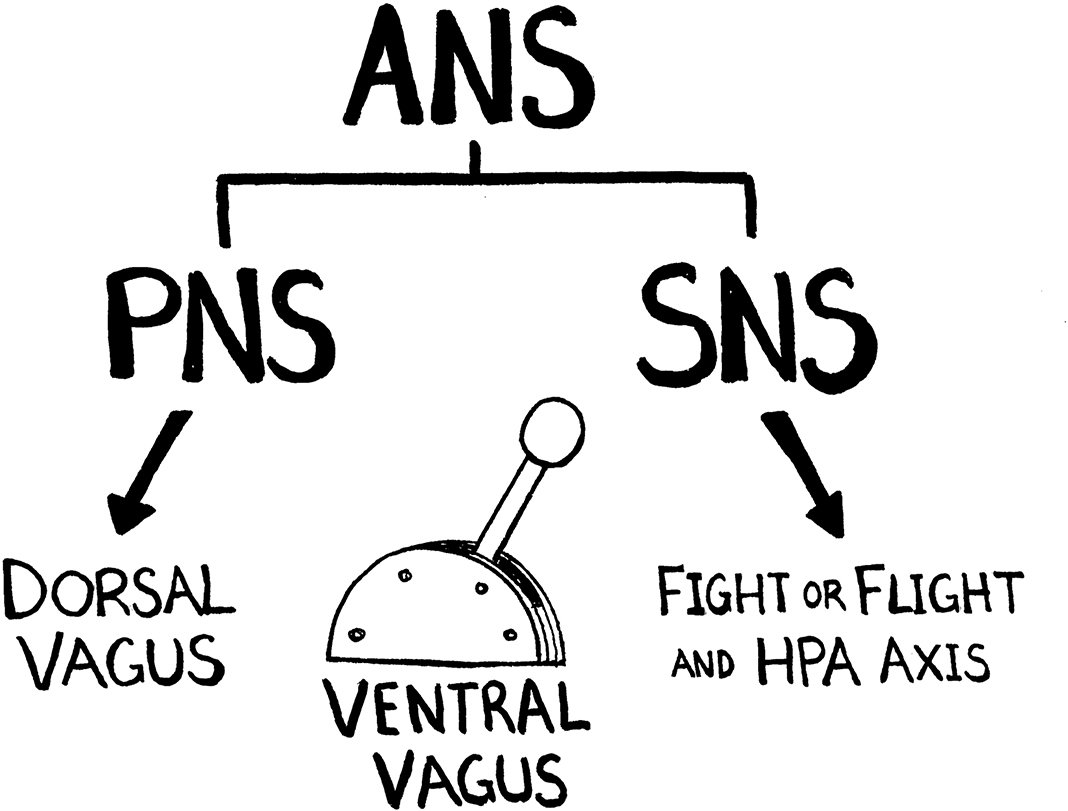

Like all our thoughts and behaviors, the complementary push-me/pull-you relationship between ordinary states of mind and states of emergency operates at a neurobiological as well as a psychological level. These changes are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). This is the system that controls automatic bodily functions such as respiration, sleep, and digestion, and the physiological responses that generate emotion. It is actually an ur-system, composed of many different interactive systems throughout the brain and body. When we’re safe and in business-as-usual mode, our systems are dominated by the branch of the ANS called the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), again, a system with many subsystems. The PNS enables ongoing processes like digestion and growth, as well as clear thinking and social engagement.

But when the environment poses danger, be it a snake in your path, a nasty rival, or an unexpected rejection, the sympathetic division (SNS) of the ANS takes over. Like the PNS, this subsystem coordinates activities throughout our brains and bodies. It’s actually responsible for all our excitatory physiological responses, both positive and negative. Two of its most important subsystems associated with stress are the fight-or-flight response, which generates an immediate response to danger, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, better known as the HPA axis response, which activates some time afterward (although this can be just minutes later) and which is necessary for a sustained response to stress. The primary chemical associated with fight or flight (and other excitatory responses) is adrenaline (Adrenaline is called epinephrine in the U.S., but the British term adrenaline is nevertheless the more widely known term. When have you heard someone speak of a rush of epinephrine?) Other chemicals known as glucocorticoids, particularly cortisol, are released with an HPA axis response, although adrenaline also continues to enter the system. Prolonged exposure to cortisol isn’t good for us.†

The more social the animal, the more possible it is for stress responses to activate in response to social as well as physical dangers. Elinor was about as physically safe as a person can be in Lady Middleton’s drawing room, where Lucy told her about the secret engagement. But this encounter put her into crisis mode nevertheless. This move toward extending the scope of crisis responses in animals, including humans, was likely related to the increasing importance of social ties to survival.

How we switch from one system to the other—the dance of emotion and its regulation—plays out at the nuts-and-bolts level of brain function in especially interesting ways. Stephen Porges and his colleagues have formulated a convincing and widely accepted theory, which is beginning to impact therapeutic practice. This is “the polyvagal perspective” (also known as the “polyvagal theory”). It is called a perspective rather than a system because it’s really a way of viewing how the ANS works and what it does.

It can be confusing to read about the polyvagal perspective because it does have many system-like qualities, such as divisions and parts. For instance, the fight-or-flight response and the HPA axis are functions of the SNS, but they are also the second of our significant ways of responding to experience (adverse experience, of course), from a polyvagal perspective. When you look at the ANS‡ from the polyvagal perspective, you see the areas and functions that constitute its master switch; this is primarily the vagal brake, which we’ll look at in a moment. The vagal brake is the mechanism that regulates the extent to which the PNS and SNS each activate. The polyvagal perspective therefore highlights those areas and functions that rule the ANS, determining the input from its subsystems, and thus also determining how our bodies and brains respond to the environment at each and every moment. The polyvagal perspective considers those responses within the context of whether the environment is threatening or safe.

The polyvagal perspective divides into three areas of focus. The first is the ventral vagus, so-called because its neurons run closer to the ventral side of the brain, the side where our stomachs are located. (Ventrus is Latin for “stomach.”) This is also called the “smart vagus.” The second area of focus is the SNS, its fight-or-flight and HPA axis responses. The third is the dorsal vagus, whose circuits run closer to the back of the brain. (Dorsum is Latin for “back.”)

The vagus nerve originates in the brainstem, the brain’s most primitive and lowest part, continuous with the spine; the ventral vagus is one of its branches. In one direction, the ventral vagus connects to the heart’s pacemaker, a muscle called the sinoatrial node; it actually extends into the body to do this. A crucial function of the ventral vagus is to vary heart rate in order to enable us to match our reactions to what the environment requires.

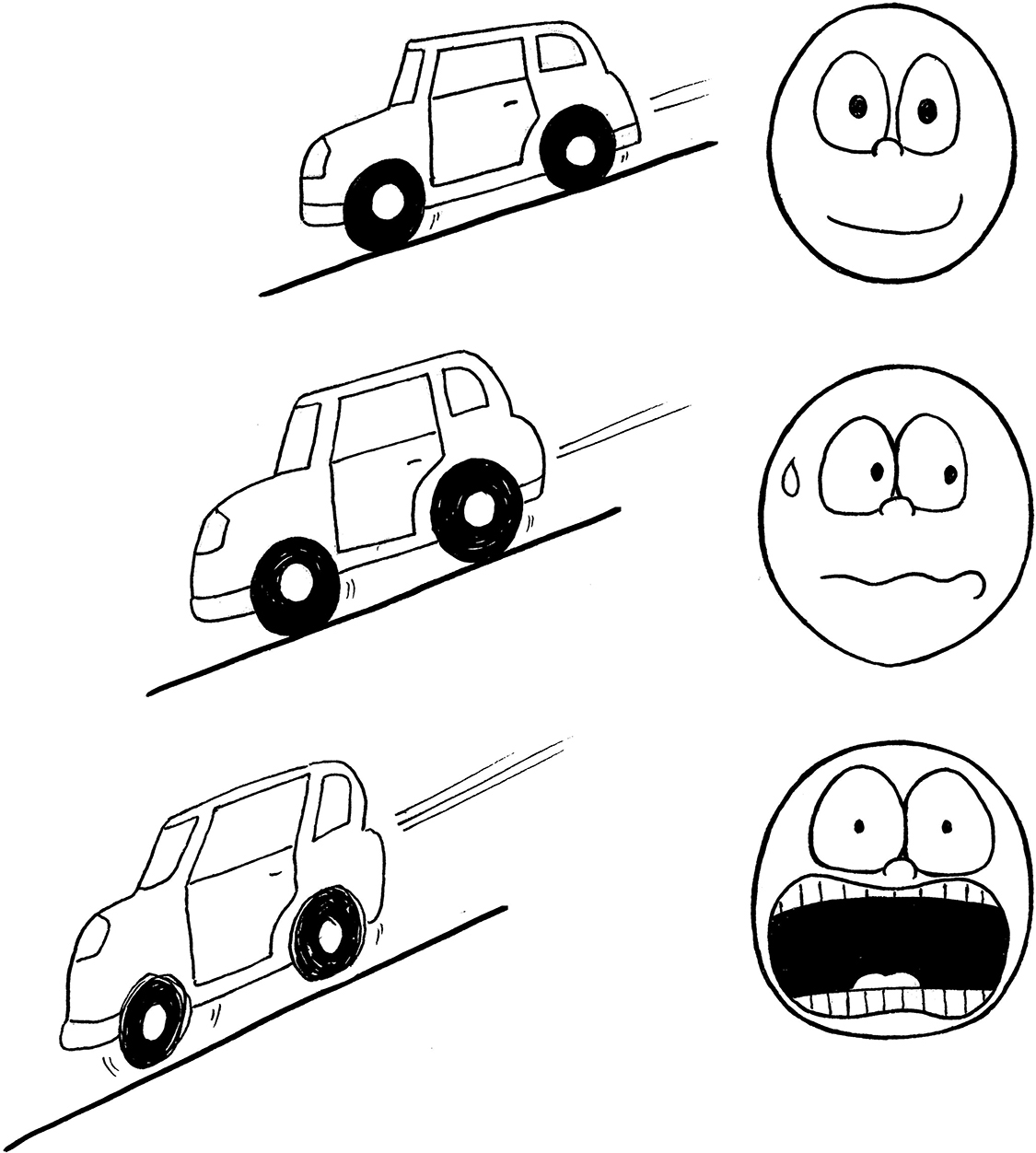

As you know, heart rate is an indicator of excitement—I’m sure Elizabeth’s heart races when she unexpectedly sees Darcy at Pemberley. Heart rate is also the primary catalyst for changes within ANS. Increases and decreases in heart rate are registered by other brain and body areas that then respond accordingly. Among its most important functions, increased heart rate activates the SNS, and if the heart rate is sufficiently accelerated we go into fight-or-flight, “red alert” mode, and if a threat is sustained, HPA axis mode. If excitement is not required, heart rate slows down, and other excitatory bodily processes also cease, such as the release of adrenaline. Porges calls the part of the vagus nerve that extends to the sinoatrial node “the vagal brake,” an automotive metaphor, because it increases and decreases heart rate, just as the brake on a car regulates speed.

Under ordinary circumstances, the vagal brake keeps our heart rate low so that the PNS, business-as-usual system dominates. When we experience strong emotions, the vagal brake is lifted, and the increase in heart rate signals to the brain and body to increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. This is true whether the emotions we experience are positive or negative, although the polyvagal perspective looks at responses to threats and dangers. Incidentally, the command to lift or lower the vagal brake comes primarily from the OFC, that major hub of emotional processing. If you see a snake-like object or a mean girl in your path, the amygdala sends a signal to the OFC, which relays the information to the smart vagus.

The automotive metaphor of a vagal brake makes sense if you think about driving downhill rather than on a level surface. You need to press the brake to keep cruising at an acceptable speed. Without the restraint of the vagal brake, we would quickly go downhill biologically. The heart would beat much more quickly, initiating sympathetic stress responses. And we all know how unhealthy it is to live in a constant state of stress. Actually, without any vagal restraint, the heart would beat too quickly to sustain life. People who are poor at regulating their emotions are said to have poor vagal tone; efficient self-regulators have good vagal tone. Elinor has better vagal tone than Marianne.

The smart vagus controls heart rate in one direction, which induces shifts between sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. In the other direction, it connects to important parts of the social engagement system, which is the set of brain areas involved in emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that activate when we engage socially with others. This part of the vagus is known as the tenth cranial, or head nerve; actually, all cranial nerves are clusters of nerves, just as the optic nerve is not a single nerve but a cluster. In particular, the smart vagus (tenth cranial nerve) controls muscles of the head and face, most crucially around the eyes, which are so important for signaling emotion. It also connects to the stapedius muscle in the ear, which opens passageways to increase our capacity for hearing, vital to conversation. Really angry people might not be able to listen to reason not only because logical thought is impeded during fight-or-flight mode, but also because they literally aren’t hearing well.

In addition to inducing both states of emergency, stress, and calm, the smart vagus induces all the states of mind and body that we experience between these extremes. States of rage or terror—full sympathetic dominance—rarely last for long before we return to a less extreme mode of response. Elinor was dumbfounded at Lucy’s confession, but the peak of her upset quickly subsided. Emotions impeded her ability to speak for only a moment before parasympathetic regulation began to function again, at least to some extent, and she was able to think clearly enough to answer Lucy.

So while the mutually exclusive relationship between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity applies to extreme emotional states, most of us don’t live on the edge in this way. By linking heart rate in one direction with facial expression in the other, the smart vagus connects emotional states, which depend on bodily responses, with facial expression. In other words, in addition to controlling heart rate, which then influences other systems throughout the brain and body, the smart vagus controls our facial expressions, which let people know that we’re angry or embarrassed or happy or preoccupied, or any of the other myriad states that our supremely mobile facial muscles are able to convey. Recall that psychologist Paul Ekman studied his face in the mirror for a year to chart the connection between emotional response and facial expression.

Bodies tell faces how to act, but influence can go in the other direction; adopting a given facial expression induces its accompanying emotions to some extent. The vagal perspective describes a complex system (like all systems in the mind-brain, including the mind-brain as a whole), which means that intervention at any point can affect the whole. However, this influence is subtle and obviously limited, or we’d only have to “put on a happy face” to banish distressing emotions. Obviously, this doesn’t work well enough to have banished the painful feelings all of us experience at one time or another.

It makes sense that our systems evolved to include a continuum of excitability rather than all-or-nothing alternatives. If an animal is in danger or some other kind of demanding situation is occurring, resources are needed to deal with the emergency at hand, and so cognition shuts down or shifts to automatic pilot. But being able to think clearly is obviously an advantage in all kinds of situations, which is why the ability to down-regulate intense emotions quickly is just as important as the ability to go on red alert.

The careful balancing act between the SNS and PNS applies to positive as well as negative emotions. Although destructive emotions tend to take over with greater force than positive emotions, the latter can reach the fever pitch we associate with fear, anger, and other negative emotions. We can be stymied as the result of rapture as well as rage. When Elinor bursts into tears of joy at finding Lucy has married Edward’s brother, she’s incapable of doing anything but cry. This isn’t a respectable or decorous response—it’s worthy of Marianne in her pre-depression days—especially since Edward is the one who conveys the news. Elinor’s tears of joy and relief confess her love before Edward has made a formal declaration of his own feelings, definitely a transgression in Austen’s day. Even those with strong vagal tone can be overwhelmed.

Along similar lines, I was in the grocery store recently, where I overheard someone say, “I was so ecstatic I couldn’t think straight!” Whether or not he was exaggerating, he expressed a common way of feeling that was recognizable to all his listeners. Elinor’s reaction is not uncommon. Positive as well as negative feelings can interfere with clear thinking. (By the way, because I was thinking about emotion and reason, that sentence in the grocery store leaped out at me from among all the other conversations that were happening at the same time. Neuroscientists call this priming. If you’re thinking of a subject, the neurons that form ideas related to this subject are prepared to fire should you encounter it in the environment; they’re “on the lookout” for what you’ve been thinking about. Have you ever noticed how once you learn a new word, you start encountering it everywhere? It’s also possible that I imagined what I heard, that someone said something different but I heard a sentence in line with my own thinking. The power of the human brain to find what it seeks shouldn’t be underestimated.)

This comment overheard about the cognitive effects of “ecstasy” brings to mind an old joke popular with biologists: The sympathetic system dominates during the four f’s, the basic drives that all animals share: feeding, fighting, fleeing, and, euphemistically, mating. (We’ll talk about a fifth “f” in a future chapter.) But actually, most people in caring, intimate relationships would probably say that they remain emotionally engaged during most of what goes on during that fourth “f.” Such involvement signals parasympathetic input, although the actual moment of orgasm might involve sympathetic-system takeover. Indeed, all approach behaviors, all the positive emotions that come into play when we seek rewards, need the excitement that comes with sympathetic input because energy and motivation depend on this. But at the same time, most positive emotions are also characterized by a sufficient degree of calm for us to be able to think clearly about what we’re experiencing, and to maintain excitement at physiologically healthy levels.

In short, in most instances of both positive and negative emotion, you never release your foot fully from the brake so that you’re dangerously careening downhill, nor do you come to a full stop. Such a mixture also characterizes the variety of conflicting feelings that humans are so prone to feel, especially in complicated or delicate social situations. When Edward arrives at the Dashwood cottage to tell of Lucy’s marriage and ask Elinor to be his wife, he feels embarrassment and confusion as well as hope, as his stammering and blushing clearly show. When he actually tells Elinor that Lucy has married his brother, information that sends her from the room running and sobbing, Edward is certainly overjoyed to convey the news of his lucky escape and his availability. But he’s also embarrassed for his past behavior and anxious as to whether Elinor will be willing to marry him. He’s so overwhelmed by his medley of conflicting feelings that he simply leaves: “he quitted the room, and walked out towards the village.”

According to the polyvagal perspective, the ventral, smart vagus is the first part of the ANS. The fight-or-flight and HPA axis functions of the SNS make up the second part. The third division, the dorsal vagus, involves the PNS, the calming division of the ANS. This too involves a response to crisis, freezing, the third “f” in our emergency response system of “fight, flight, or freeze.” Freezing is an older, more primitive response that kicks in when we’re so overwhelmed that fight or flight feels inadequate or useless to protect us, or so we sense, since this decision doesn’t involve conscious thought.

Freezing involves an evolutionarily older neural pathway that uses a different branch of the vagal nerve (and so originating in the brainstem), the dorsal vagus, whose circuits are routed closer to the back of the brain. This pathway initiates a different response to danger, the third “f.” Freezing refers not only to immobilization, the “deer in the headlights” phenomenon, but also to fainting and other forms of response associated with slow rather than accelerated heart rate, and shutting down rather than revving up.

The dorsal vagal response developed because if an animal freezes, it’s less likely to be noticed by a predator, perhaps mistaken for an inanimate object or a dead animal. An example with regard to the human social brain can be seen in Marianne’s reaction to Willoughby, when they finally meet at the ball in London where he snubs her:

Marianne, now looking dreadfully white, and unable to stand, sunk into her chair, and Elinor, expecting every moment to see her faint, tried to screen her from the observation of others, while reviving her with lavender water.

Marianne is indeed like a deer frozen in the headlights, immobilized by Willoughby’s behavior. Of course, Marianne doesn’t freeze because she’s pursued by a predator, although Willoughby has had a predatory relationship with the woman he seduced and abandoned. But the loss of his love feels so shocking and dangerous to her general sense of well-being that a fight-or-flight emergency response doesn’t feel adequate to the subconscious parts of her brain/body that make these decisions. In terms of the automotive metaphor, when the vagal brake is lifted, the car begins to travel so quickly that it crashes, turning off the HPA response. Freeze mode follows.

A brief recap. The autonomic nervous system consists of two divisions: the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which dominates when we’re on an even keel, and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which dominates when we’re in excitatory mental and bodily states. The vagal perspective highlights those parts of the ANS that determine the degree of input from each of its divisions. The ventral or smart vagus controls the switch between systems by controlling heart rate. It regulates activation of the PNS, including normal bodily functions and the capacity for social engagement, and the SNS, which contributes to normal states of excitement as well as high-stress modes. Most of the time, we experience states of mind that involve input from both systems. The second focus of the vagal perspective references sympathetic stress responses, fight or flight for immediate dangers, and HPA axis activation for ongoing threats. The third part of the vagal perspective, the dorsal vagus, refers to freeze mode; you might think of this as parasympathetic dominance gone haywire so that it shuts us down rather than calms us down. From the polyvagal perspective, aspects of the vagal functioning succeed one another. When excitement is too much for business as usual, including interacting with others in a regulated fashion, which is orchestrated by the ventral vagus, the vagal brake is lifted and stress modes predominate, fight or flight to begin with and HPA axis activation subsequently. If fight or flight isn’t up to handling an emergency to begin with, the dorsal vagus takes over.

Humans and other mammals have been formed by the conflicting pressures of evolution to arrive at a compromise: highly reactive emergency systems that can nevertheless be dampened sufficiently so that we can think. But while this confers flexibility, it has its downside; many of us develop the ability to be both anxious and strategic. Some people spend way too much time in stress mode with cognitive powers fully intact. This might indeed be a prerequisite for many jobs. But before we blame evolution, let’s remember that our Paleolithic brains were not meant for a twenty-first century world, or even an nineteenth-century world.

Hume, Austen’s favorite philosopher, believed that what we think of as reason is really a form of passion, or feeling. We’ve certainly seen this with Willoughby, whose reasonable decision to marry for wealth and status clearly matches his desires. Scratch the surface of reason, and you’ll find it’s a thin veneer covering affect.

We also see this with Marianne, who snaps out of her depression not as a result of deliberate self-control, or the triumph of reason, but because time and reflection lead her to more positive feelings. As a therapist, I’ve spoken to many people who lament their depression saying that other people have it worse: “I shouldn’t feel this way.” You’ll have more success fighting an E-ZPass fine than your own feelings.

Although deliberate efforts to self-regulate can succeed, this isn’t because reason gets the better of feeling. Reason, or logical thinking, can help us to regulate emotion only by shifting our focus to thoughts that bring calm or positive emotions in their wake to replace turbulent or negative ones. Reason can help us to reframe our thoughts so that different feelings come into play. Reason can also distract us, activating cognitive areas that are dormant when we’re upset.

Elinor’s effort to deal with her sadness and anxiety about Edward’s strange behavior and obvious melancholy during his visit illustrates this point. As soon as he leaves, Elinor attempts to distract herself in order to keep her thoughts from dwelling on Edward: “Elinor sat down to her drawing table as soon as he was out of the house, busily employed herself the whole day, neither sought nor avoided the mention of his name, appeared to interest herself almost as much as ever in the general concerns to the family.” But as soon as conversation and activity cease, she’s left to her own reveries, “to think of Edward, and of Edward’s behaviour, in every possible variety which the different state of her spirits at different times could produce: with tenderness, pity, approbation, censure and doubt.” Enough turbulent feelings here for even the most romantic of Austen’s readers!

By focusing on activities that engage her attention, Elinor gives herself a break from her troubles. She doesn’t tell herself to stop thinking of Edward, or try to argue herself out of her feelings, but directs her attention elsewhere. Paying attention to mundane activities brings the mundane feelings that accompany them into play. By redirecting her attention, she also activates cognitive brain areas that inhibit stress reactions, drawing on the inverse relationship between parasympathetic and sympathetic systems. She shifts attention away from distressing thoughts, and so encourages the restraint of the vagal brake.

Marianne learns to do this as well. As she slowly recovers from her illness, she determines to follow Elinor’s example and to ward off her feelings of disappointment and grief, rather than courting and encouraging them as she used to do. She determines to follow a disciplined course of study, music, and exercise. When she encounters the many places and things in Devonshire that remind her of Willoughby, she resists despair by directing her mind elsewhere. One poignant instance occurs as she sits down to play the piano:

[T]he music on which her eye first rested was an opera, procured for her by Willoughby, containing some of their favourite duets, and bearing on its outward leaf her own name in his hand writing. That would not do. She shook her head, put the music aside, and after running over the keys for a minute complained of feebleness in her fingers, and closed the instrument again; declaring however with firmness as she did so, that she should in future practise much.

Rather than tumbling into an abyss of pain and memory, Marianne anticipates a future of productive work. She can’t fully divert her attention away from her sadness at the moment, but she anticipates a time when she’ll be able to do so, and that in itself redirects her focus and her feelings.

Controlling our attention is one way in which we can use reason, or cognitive skills, to think ourselves into a better frame of mind. This is the basis of mindfulness, which has become a popular topic within the general population as well as a significant object of study for mind-brain scientists. Mindfulness means being aware of the current moment, of anchoring one’s mind completely in the present rather than allowing it to dart through time and space and memory, as minds tend to do. It means stepping back and watching the world, including the world of your own feelings. Such watching involves emotions such as curiosity and tolerance. If you can step back and watch your own anger, you’re no longer completely driven by it. Ditto if you can concentrate on a drawing. Your attention and its concomitant emotions have shifted away, at least to some extent, from the upsetting and the negative.

But this is not reason. It’s not arguing with yourself or suppressing your feelings or trying to become Mr. Spock, the famous character from Star Trek who embodies “pure reason,” whose responses are logical rather than emotional (and even he has trouble being Mr. Spock). Marianne escapes the grip of a destructive sensibility only when she can sense alternative and healthier modes of being and feeling, and only when she commits herself, heart as well as mind, to finding her way along a new and better path.

* The lead writer on the paper that first reported this research was Damasio’s student, Ralph Adolphs; this means that Adolphs directed the research. Daniel Tranel was the second author listed. Both are currently professors and major researchers in the mind-brain sciences. Damasio subsequently reported and popularized the findings of this team in Descartes’ Error, and he has continued to work throughout his career with S.M. and others whose emotional processing areas have been damaged.

† These two responses to stress involve two pathways. In the fight-or-flight response, the hypothalamus sends a chemical message to the adrenal glands (to the medulla, an area inside of each gland). The adrenal glands are located on the top of each kidney. These glands then release adrenaline, the primary hormone involved in fight or flight. Adrenaline helps to initiate sympathetic arousal. This pathway is called the “sympathomedullary pathway” or SAM. In the HPA-axis response, the hypothalamus sends a chemical message to the pituitary gland, located directly below it; the pituitary gland then releases a hormone called ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone), which travels to the adrenal glands (to the cortex, or outside area, of each gland this time). The adrenal glands then release the hormone (steroid) cortisol, a glucocorticoid, which helps the body maintain blood sugar levels needed for dealing with prolonged stress. Glucocorticoids are helpful to begin with, but when they circulate for too long in the bloodstream, they become harmful. The hypothalamus (the “H” of the acronym HPA) is a small area directly above the brainstem. It’s called the hypothalamus because it’s located beneath the thalamus, a much larger brain area. The hypothalamus might be a relatively small structure with a derivative name, but make no mistake: It’s one of the brain’s most important areas, involved in the regulation of bodily functions.

‡ Recall that ANS stands for autonomic nervous system, which contains the sympathetic nervous sytem (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).