May–June 1916

In late May 1916, anyone climbing the heathery hills of Hoy in the Scottish Orkney Islands could have peered through the mist of the vast Scapa Flow inlet and seen one of the most magnificent sights in naval history. For here was the home of the British Grand Fleet. Almost as far as the eye could see sat row upon row of battleships, battlecruisers, cruisers, destroyers – and scores of lesser vessels scurrying between these deadly ships with supplies, men and messages. Each ship was spaced at a neat interval and at exactly the same angle to every other – a visible representation of the discipline and tradition of this most prestigious fighting force. And, astonishingly, the power of the British navy did not end with this vast collection of ships. There were other bases too, at Cromarty, Moray Firth and Rosyth, along the eastern coast of Scotland. Each contained a formidable battle squadron of warships, all under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe.

At the time of the First World War, Britain had the greatest fleet in the world. They needed it too. Island Britain had an empire that stretched from the Arctic to Antarctic Circles. Their warships protected the fleets of cargo ships which carried goods and raw materials to and from British colonies. During wartime, the warships also prevented cargo ships from delivering goods to Britain’s enemies. Most crucial of all, the British fleet ensured that supplies and troops from England could sail safely across the Channel to the Western Front in northern France. Only Germany had a fleet powerful enough to threaten the British. As the head of state of an up-and-coming superpower, Kaiser Wilhelm II had wanted to build a rival navy to complement Germany’s growing importance in the world. But Wilhelm’s policy was a double-edged sword. His insistence on building a powerful navy had soured previously good Anglo-German relations, and had been one of the main reasons Britain joined France and Russia against Germany when war broke out.

Today, it is difficult to imagine the hold battleships had on the imagination of people at the start of the 20th century. In the early 21st century, such weapons are largely obsolete; aircraft carriers, warplanes with their formidable arsenal of bombs and missiles, and the intangible threat of terrorism are the stuff of modern warfare. But, at the start of the First World War, the battleship was considered the superweapon of its day. The largest and most heavily armed battleships were known as dreadnoughts – after HMS Dreadnought, the first of their kind, launched in 1906. Dreadnought weighed a formidable 17,900 tons and packed a mighty punch with ten 12-inch (30cm) guns (a 12-inch gun fired a shell that was 12 inches wide). By the time war broke out many of these dreadnought battleships had even bigger guns – 13.5-inch (34cm) monsters, that could fire a shell weighing 640kg (1,400lb) over 21km (13 miles). These guns were housed in pairs in large turrets, usually at the front and rear of the ship. Such weaponry gave the battleship its ferocious bite. Each gun turret had a crew of around 70 men, split into teams who performed the complex task of bringing up shells and propulsive charges from the ship’s magazine, and then loading, aiming and accurately dispatching them. Working in such a turret could be exceptionally dangerous. If an enemy shell hit the turret, the entire mechanism would be engulfed in a massive explosion, killing everyone inside it.

HMS Dreadnought overshadowed every other warship afloat. Not only was it very powerfully armed, it was fast and shielded by a thick metal protective covering. This ship carried a crew of over a thousand men, and was nearly 215m (700ft) from bow (front) to stern (rear). The arrival of HMS Dreadnought began a ruinously expensive arms race between Britain and Germany. By the time war broke out, Britain had built 28 such ships, and Germany 16.

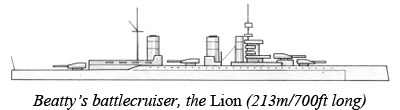

The revolutionary dreadnoughts were also joined by another new kind of warship, the battlecruiser. The first of their kind was HMS Invincible, launched in April 1907. Battlecruisers were smaller but almost as heavily armed as dreadnoughts, with eight 12-inch (30cm) guns. They were faster than battleships, having a top speed of around 25 knots, compared to a battleship’s 21. But this speed was gained at the expense of lighter protection.

When war began in August 1914, a full-scale confrontation between the British and German fleets seemed inevitable – in fact, both countries had built up their massive navies to face such a task. The German fleet may have been smaller than the British fleet, but its ships were better designed. The Germans also made very effective use of their U-boats, sinking so many cargo ships bound for Britain that the country was often in danger of starvation. But, throughout the war, the British never lost control of the sea. The Royal Navy placed a blockade around German waters, preventing vital goods from getting in. This caused great difficulty for Germany’s war industries, and ensured that there was never enough food for her home population.

Barely six months into the war, the German battlecruiser Blücher was sunk in the North Sea, with great loss of life. The disaster led to the sacking of the German navy commander-in-chief, Admiral Ingenohl. But it also encouraged his successor, Admiral Hugo von Pohl, to be extremely cautious. Then, in February 1916, suffering from ill health, von Pohl resigned. He was replaced by Admiral Reinhard Scheer, a far more aggressive and daring commander-in-chief.

For the first two years of the war, each navy had tested the strength of its opponents, tentatively pushing and probing, engaging in small-scale skirmishes, with only the occasional battle. But, as the carnage of the Western Front continued with no visible benefit to either side, pressure mounted on the German navy’s High Command to force the British into a do-or-die battle that could tip the balance of the war Germany’s way.

Scheer decided that the German fleet would try to lure the British into the North Sea for a grand confrontation. Today, such a move would be called a “high-risk strategy”. If Scheer succeeded, the war would be as good as won. With its fleet destroyed, Britain would be unable to prevent a German naval blockade around her coastal waters. Food supplies would quickly run out, and the country would starve. British troops and supplies would no longer be able to travel safely across the Channel. The great British politician Winston Churchill once described Admiral Jellicoe as the only man who could lose the war in an afternoon. In the early summer of 1916, Jellicoe had the chance to do just that.

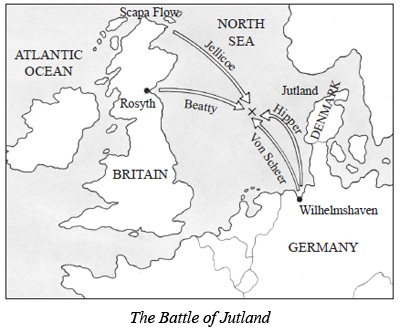

Scheer’s plan was simple enough. He would send a battlecruiser squadron into the North Sea, under the command of Admiral Franz von Hipper. Then he would follow at a distance with his High Seas Fleet. The British, it was hoped, would send out their own battlecruisers to intercept Hipper’s ships. These would almost certainly come from the base at Rosyth, which was the nearest to the outgoing German ships. When the British were sighted on the horizon, Hipper would change course, and lead the enemy back to Scheer’s main battle fleet. Here, outnumbered, they would be destroyed.

The plan also assumed that the main British naval force – the aptly named Grand Fleet – would take to sea too, from the more northerly base of Scapa Flow. Here, Scheer meant for lurking U-boats to pick them off as they sailed to intercept him; and he intended to use zeppelins to keep watch on the British navy and radio in information on the movements of their ships.

But, like many simple plans, there were unforeseen hitches…

On May 31, 1916, Scheer put his plan in motion. From bases on the northern coast of Germany, the High Seas Fleet took to sea. Admiral von Hipper set out ahead with five battlecruisers and another 35 smaller ships, to try to lure the British navy into battle. Scheer followed on, in the battleship Friedrich der Grosse, accompanied by 60 other battleships, battlecruisers, cruisers and destroyers, and sundry smaller boats. By one o’clock that afternoon, the two German squadrons were way out in the North Sea, 80km (50 miles) apart.

As they had intended, von Hipper’s squadron was soon sighted by the British reconnaissance ships that patrolled the coast off Germany. British intelligence had also picked up and decoded German radio signals which indicated that there was a build up of German ships in the North Sea. As foreseen by Scheer, Admiral Jellicoe immediately ordered his Rosyth battlecruiser squadron, under Admiral Beatty, to take to sea. But, unknown to Sheer, Jellicoe was already at sea with his Grand Fleet, patrolling an area of the North Sea known as the “Long Forties”, 180km (110 miles) east of Aberdeen. Jellicoe ordered the Grand Fleet to head south and follow Beatty. Between them, the two British admirals had 149 ships under their command.

The stage was set for an epic confrontation. To this day, no greater naval battle has ever taken place. The opposing admirals, perched high in command posts above the decks of their ships, began a game that was a strange combination of hide-and-seek and chess. At stake were the lives of 100,000 sailors, the fate of nearly 250 ships and, quite possibly, the outcome of the First World War. Jellicoe, particularly, was hoping for a victory to match Trafalgar. There, in 1805, the Royal Navy under Admiral Nelson had destroyed the French and Spanish fleets, and left Britain in undisputed control of the sea for the next century.

Right from the start, Scheer’s scheme did not go to plan. The U-boats stationed outside the bases on the Scottish coast failed to attack the British ships as they emerged to patrol the North Sea. A technical problem meant that wireless orders permitting them to engage their enemy were never received.

Scheer’s novel use of zeppelins as reconnaissance aircraft was also a failure, due to bad weather and poor visibility. The zeppelins could see almost nothing through cloud or foggy haze. This was a major drawback. Today, thanks to radar and satellite surveillance, navy commanders can detect an approaching enemy long before his ships or aircraft are even over the horizon. In 1916, navy ships and guns were immeasurably more sophisticated and powerful than those used by Nelson at Trafalgar; but their communication and detection technology was much the same. Scheer and Jellicoe might have had guns which could fire a heavy shell 22km (14 miles), but they still looked for their enemy with a telescope and naked eye. Also, due to the danger of wireless communications being intercepted by the enemy, in battle they still preferred to communicate with their ships using signal flags and semaphore (a method of ship-to-ship communication whereby particular hand positions, indicated by a sailor carrying two flags, stand for the letters of the alphabet).

Early that afternoon, neither admiral knew the size of the enemy fleet fast approaching them. The British thought only Hipper’s squadron was at sea. And Scheer had no idea he was soon to face the entire Grand Fleet.

Beatty’s fleet first sighted von Hipper’s ships at around two o’clock, when they were about 121km (75 miles) off the Danish coast of Jutland. Thereafter, the epic confrontation that followed would be known as the Battle of Jutland.

The first shots were fired about 15 minutes later, between small scout ships, which sailed ahead of the main fleets. The day was quite hazy, and the sun was now well behind the German ships, giving them a much better view of their approaching enemy.

Beatty sailed forward to engage von Hipper’s forces. By then, it was around half past three. Beatty knew the Grand Fleet was coming up behind him, but he would be on his own for several crucial hours before Jellicoe caught up with him. Hipper, in turn, knew he had to lure Beatty’s ships into the jaws of the High Seas fleet behind him. As they had done in the days of Nelson and Trafalgar, both fleets sailed “in line” – that is, one after the other, in tight formation.

At ten to four, the battlecruisers began firing at each other. The odds seemed to be on Beatty’s side. He had six battlecruisers, where Hipper had five. Almost immediately, firing between the opposing forces was so constant that each squadron seemed to be navigating its way through a thick forest of towering shell splashes. Bizarrely, in the No Man’s Land between the fleets, a small sailing boat sat motionless. Its sails hung limp in the still air as deadly shells whistled and screamed, arcing high over the heads of the hapless sailors on board.

The superiority of the German guns and ships soon became obvious. Just after four o’clock, just 12 minutes into the fighting, the British battlecruiser Indefatigable became the first major casualty of the day. The German ship Von Der Tann had landed three shells on her almost simultaneously. Indefatigable disappeared in a vast cloud of black smoke, twice the height of her mast, and fell out of line, as she was hit by two more shells from Von Der Tann. Inside Indefatigable something terrible was happening. Searing flames were gnawing at her ammunition supplies. Thirty seconds after the second shells hit home, the entire ship exploded, sending huge fragments of metal high into the air. She rolled over and sank moments later. Only two men on board survived, rescued by a German torpedo boat.

Among several other British ships, Beatty’s own battlecruiser Lion was hit, when a shell penetrated the central turret, blowing half the roof into the air and killing the entire gun crew. The roar of the guns, and the whistle of the shells as they approached, was enough to distract anyone from what was happening to other ships around them. Aboard the Lion, Beatty barely noticed the loss of Indefatigable. He had enough troubles of his own. Six shells from von Hipper’s flagship, the battlecruiser Lützow, hit his ship within four minutes, and fires raged on deck and below. Half an hour later, another explosion caused by slow-burning fires shot up as high as the masthead. But the Lion, and Beatty, survived to fight on.

The other British ships fighting alongside had to contend with similar problems. Twenty minutes later, the battlecruiser Queen Mary blew up too, breaking in half and sinking within 90 seconds. When the ammunition supplies exploded, the huge gun-turret roofs were blown 30m (100 feet) into the air. Only eight men survived from the entire ship. One of them was gunner Ernest Francis.

When the Queen Mary began to sink, he called out to his comrades around him: “Come on you chaps, who’s coming for a swim?”

Someone replied, “She’ll float for a long time yet.”

But Francis knew in his bones he had to get away. Diving into the freezing, oily water, he began to swim as fast as he could away from his ship. Within a minute there was a huge explosion, and chunks of metal filled the air around him. Only diving deep beneath the waves saved him from being killed by flying fragments. When he reached the surface, gasping for breath, he was immediately dragged under again by the downward suction of the ship as it sank. Beneath the water, he felt utterly helpless and resigned to death.

“What’s the use of your struggling?” he said to himself. “You’re done.”

But something made him strike out for the surface. Just as he was about to lose consciousness, he broke through the waves. Ahead was a piece of floating debris, and Francis wrapped his wrist around a rope trailing from it before he became unconscious. Eventually he was rescued, but not before an earlier ship had picked up the few other survivors, leaving him for dead.

Beatty had seen the destruction of the Queen Mary at close hand. In the strange and rather callous manner of the British upper class at war, he remarked on the loss of the Queen Mary and Indefatigable, and over 2,000 lives: “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.”

There was something wrong with the British ships: they were badly designed. German warships had solid bulkheads (the partitions inside a vessel), passable only by going to the upper deck and then down into the next section. British ships had bulkheads with doors that permitted passage between them. This was far more convenient, of course, but a serious weakness when a massive explosion ripped through a ship. The British also had a much more careless attitude to their ammunition. German shells were kept locked away in blast-proof containers until they were ready to be fired. British gunners piled their shells next to their guns. So they were far easier to set off accidentally if the ship was hit.

But Beatty’s sang froid in the midst of the partial destruction of his own ship was admirable too. Unlike army generals who direct land battles from headquarters behind the front line, when fighting starts at sea, an admiral has just as much chance of being killed by an enemy shell as the most humble seaman.

Moments after the Queen Mary sank, Scheer’s German High Seas Fleet was spotted steaming over the horizon to join von Hipper’s battlecruiser squadron. Jellicoe and his Grand Fleet were still 20km (12 miles) away. Beatty’s composure was being tested to the limit. Facing both Scheer’s and Hipper’s forces, and two battlecruisers down, Beatty gave the signal for a 180° turn. Scheer’s plan, to use Hipper’s forces to entice the British into the jaws of the High Seas Fleet, was now being turned on its head. As the German ships pursued the fleeing British, Beatty was now luring them into the massed fire power of the British Grand Fleet.

Shortly after five o’clock that afternoon, Scheer’s fleet had come close enough to Beatty’s retreating ships to begin attacking the stragglers. But, an hour later, Jellicoe’s fleet of 24 battleships was steaming over the horizon. No matter how good the German ships were, they were now heavily outnumbered. Scheer was in serious trouble, and he sent out an order for his ships to head north.

Jellicoe was puzzled. From his position high on his flagship Iron Duke, he could observe the enemy turning away from him; but he was suspicious. Was Scheer trying to lead them into a trap, hoping perhaps that the British would blunder into a minefield, or into the path of waiting submarines? There was too much at stake. So Jellicoe decided not to follow. Instead, his ships were ordered to head south, where Jellicoe guessed they might once again make contact with the German fleet.

Meanwhile, von Hipper’s ship Lützow had been badly damaged and he was forced to abandon her, transferring to the battlecruiser Seydlitz, and then to the Moltke. But the Lützow still managed to sink another British ship. The unlucky vessel was the very first battlecruiser, Invincible – the third major victim of the day. At half past six, a shell hit one of her gun turrets, causing a huge explosion which broke the ship in two. Of the 1,032 men on board, only six survived. For a while, both the bow and stern of this huge, 17,000-ton battlecruiser stood motionless in the water, like two church spires in a sunken village. Then the stern began a relentless descent to the bottom of the sea. The bow stayed upright until the next day, when it too sank. Those trapped inside must have spent an agonizing night, wondering what on earth was happening to them in their topsy-turvy world. Expecting to be swallowed by the sea when the ship went vertical in the water, their inevitable death was drawn out for a miserable few hours more.

As the evening wore on, Jellicoe’s intuition that the German ships would head south proved correct. Soon after seven, the two fleets sighted each other again. Scheer made several moves to try to place his fleet at an advantage to the British. Both sides were following a tactic known as “crossing the T”. The idea was to line up your fleet of warships at a right angle to your opponent’s, as they approached you in a straight line, so your fleet made the top of the “T” and the enemy fleet made the descending stroke. In that way, a commander could fire all the guns aboard his ships, both bow and stern, while his enemy would only be able to use his front guns.

But Scheer failed to outwit his enemy and, disastrously, found his ships scattered at an angle to the approaching British fleet. Worse still, the sun was now behind the British, and it was only possible to see them by the flash of their guns. At this point in the battle it was British shells that were falling with greater accuracy, while Scheer’s ships were faltering.

It was at this moment that Scheer made the most ruthless decision of the day. To avoid his entire fleet being reduced to wreckage by the much larger British force, Scheer ordered Admiral Hipper to take his squadron of four battlecruisers and sail straight at the British fleet. His signal read: “Battlecruisers at the enemy! Give it everything!” There was a cruel logic to his decision. Hipper’s fleet was made up of older and less powerful warships; Scheer would be saving his best ships to fight another day. This action has subsequently become known as the “death ride”. Scheer intended the British fleet to concentrate their fire on von Hipper’s force, allowing the rest of his High Seas Fleet to turn away and escape.

Von Hipper’s ships – Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke and Von der Tann – had been in the thick of the action since the battle began. All had sustained serious damage. As they headed out into the fading light, each ship’s captain was convinced he would not live to see the coming night. But, in warfare, nothing is predictable.

Ahead of them, Beatty and Jellicoe’s ships seemed to stretch in a curve as far as they could see. Every one of these British ships began to fire directly on the four approaching German battlecruisers. Leading these warships was the Derfflinger. Its chief gunnery officer, Georg von Hase, recorded:

“[We] now came under a particularly deadly fire… steaming at full speed into this inferno, offering a splendid target to the enemy while they were still hard to make out… Salvo after salvo fell around us, hit after hit struck our ship.”

Both the main rear turrets of the Derfflinger suffered direct hits, exploding with horrific consequences for those inside. But, thanks to good design, the rest of the ship survived. The other German battlecruisers suffered similar blows but, although they took many hits from British shells, these formidable ships were not blown to pieces.

Von Hipper was a brave commander, but he had no intention of committing suicide. Once he was sure the rest of the German fleet had escaped, his ships turned away to rejoin the rear of Scheer’s departing squadrons. Again Jellicoe was suspicious. Rather than following von Hipper’s ships directly, he turned south and raced to catch them via a more indirect route. Just as the sun was sinking on the horizon, von Hipper’s slower squadron was caught again by the British. This time, they were not so lucky. Lützow sustained more damage and would sink later that night, and Seydlitz and Derfflinger were badly damaged.

In the dark the two opposing navies continued to exchange fire, but the main action was over. The German battleship Pommern was one of the final victims of the battle. Four torpedoes from British destroyers caught her close to home, and all 866 men on board were killed.

Dawn broke around three o’clock on the morning of June 1. Jellicoe had hoped to resume contact with the German fleet at first light, but his lookouts strained their eyes over an empty sea. The German ships were in sight of their home port, and the battle was over.

The two greatest navies in the world had taken part in the one great sea battle of the First World War. In fact, it was to be the last great sea battle in history. Thereafter, battleships would never again meet in such numbers. As the century wore on, there would be naval weapons even deadlier than the great guns that battleships carried – insidious submarines, phalanxes of dive bombers and, more recently, fast and accurate guided missiles. All of these technological advances made battleships too vulnerable to be useful weapons.

Scheer’s gamble had failed, but the events of the day had shown that he had had every right to be confident. Germany’s ships were better than Britain’s, and they had proved this by sinking more of their enemy’s fleet. The British lost 14 ships and 6,274 men; the Germans, 11 ships and 1,545 men. On the day after the battle, it looked like a German victory. But, in the end, the might of the Royal Navy had prevailed. Britain still controlled the sea. Like the other grand battles of 1916 at Verdun and the Somme, a clash of huge opposing forces had taken place, and nothing had changed. Jellicoe had not lost the war in an afternoon after all. He hadn’t won it either; but he had ensured that Germany would not win it.

After the battle, the tactics employed by Jellicoe and Beatty were dissected and discussed in clinical detail. Communication between the British ships had been very poor and Jellicoe, in particular, was criticized for not attacking the German fleet with more enthusiasm. But, with hindsight, the British still came out of it less badly than the Germans. It only took them a day to recover from the battle, before Jellicoe was able to announce that his fleet was once again ready for whatever threat it might face. The German High Seas Fleet, on the other hand, never put to sea again.

The outcome of the battle of Jutland had far-reaching consequences. As the High Seas Fleet had proved unable to undermine British control of the seas, the German High Command decided to adopt a policy of unrestricted U-boat warfare instead. This meant their submarines were given permission to attack any ship, including neutral ones, that they came across in British waters. This change of tactics led to the sinking of American ships, which in turn became one of the main reasons the United States entered the war against Germany – a move which assured her defeat.

The great German High Seas Fleet remained in port for the rest of the war. Boredom and poor rations led to mutinies and, at the end of the war, revolutionary insurrection. After the armistice of November 1918, the fleet was ordered to sail to Scapa Flow while peace terms were discussed in Paris. Shortly before the peace treaty was signed in the summer of 1919, it was suggested that the High Seas Fleet should be split up and its ships given to the victorious nations. But this was too much to bear for the skeleton crews of German sailors left aboard the ships, and so they scuttled – deliberately sank – their navy in Scapa Flow. Eventually, most of these vast, magnificent warships were raised from the sea bottom and towed away for scrap. But some still remain to this day, where they are a constant source of fascination for divers.