May–June 1917

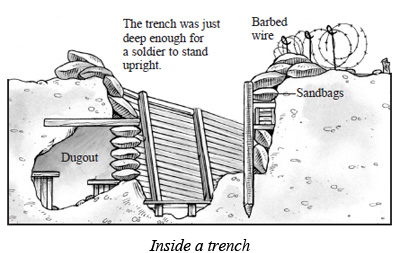

During the First World War, trench soldiers on both sides faced a kind of warfare that no one before or since has had to fight. Every day promised soldiers a gruesome death or injury from sniper fire and artillery bombardment. Once or twice a year, there would be a “big push” that tended to kill at least half the men they knew. And, along with the danger, there was the barren panorama of No Man’s Land and the unending hardship of the trenches.

Ice and snow, rain and mud, baking heat – whatever the weather, a trench was no place for men to be. Rats gnawed at their dead companions, they were perpetually plagued with lice, and any sort of plumbing system for the daily effluent of hundreds of thousands of front-line troops was clearly out of the question. In this tortured landscape, with the hideous stench of excrement and rotting corpses, the war went on, and on, and on… until those fighting believed it would go on forever. “O Jesus, make it stop!” was the heartfelt plea ending British front-line officer Siegfried Sassoon’s 1918 poem “Attack”.

But not all soldiers were prepared to carry on fighting. The British and American armies avoided any major outbreaks of rebellion, but every other major fighting nation had its share. Naval mutinies in Germany occurred in 1917 and at the end of the war. Some Austro-Hungarian troops fighting on the Eastern Front mutinied as early as 1915. Most critical of all, Russian soldiers deserted and mutinied in droves, and brought on the revolutions of 1917 which led to Russia’s withdrawal from the war.

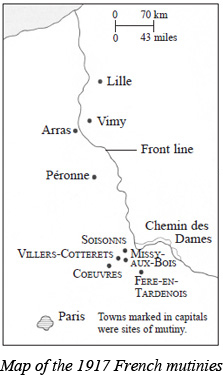

The French army mutinied too, in the spring and early summer of 1917. It was a decisive moment that could have cost France the war. Fortunately, the German generals didn’t believe the reports they received from spies and prisoners of war about the mutiny. By the time they realized it was really happening, the mutiny was over.

The word “mutiny” conjures up images of drunken violence and a descent into anarchy. It is a word to make an officer’s blood run cold. For, without order and obedience, one man cannot tell other men to carry out actions that will undoubtedly result in death and injury. Mutiny renders an army ineffective more surely than a curtain of machine-gun fire or an artillery barrage. It can lead to utter defeat in a matter of days, so it is usually punished with great severity. In ancient Rome, mutinous army legions that had returned to military discipline were subject to “decimation” – one man in ten was plucked from the ranks and executed. Who could ever have guessed that this ancient, barbaric remedy would be employed again in the 20th century, to restore order to one of Europe’s greatest armies?

The French mutinies of 1917 had their roots in German general Erich von Falkenhayn’s decision to fight the war by taking French lives rather than French territory. In February 1916, he chose the French fortress of Verdun to do this. In a horrendous 10-month battle, the French and Germans fought for possession of this stronghold. Much of the fighting took place in dank, concrete forts awash with blood, and steeped in the stark terror of men in hand-to-hand combat. When the battle ended in December that year, 350,000 French soldiers and 330,000 German soldiers had been killed or injured. There was nothing to show for all this slaughter. No territory had been won or lost. Each side had lost an almost equal number of troops. Falkenhayn was dismissed from his post. But his declared aim of “bleeding the French army white” had had more of an effect than he realized.

The French people were immensely proud of their army’s success in defending Verdun, and the soldier’s terse battle cry, “Ils ne passeront pas.” (“They shall not pass.”) became a slogan of national self-esteem. The two generals held most responsible for fending off the Germans, Philippe Pétain and Robert Nivelle, became national heroes. But, after Verdun, many French soldiers who had fought there felt they had nothing left to give.

Another major French offensive was planned in the early spring of 1917. Nivelle, still basking in his success, promised the troops a quick victory at Chemin des Dames, on the River Aisne. This, he told his men, would be the battle that would win the war. Morale was high, especially as the French soldiers were told they would be trying out a new tactic sure to save lives. They would head over to the German trenches under the protection of a “creeping barrage” – a hail of shells which would fall in front of them, gradually advancing like a protective wall of fire. Tanks would be used too – a new type of weapon which promised to crush defensive barbed wire and destroy the deadly machine-gun nests, which could sweep away scores of men with a single burst of fire.

A million men took part in the attack on April 16. It failed pitifully, and the same senseless slaughter ensued. The tanks broke down and the artillery bombardment failed to destroy the enemy strongpoints. The weather didn’t help; the French soldiers often had to advance in driving rain. After 10 days, 34,000 men had been killed, with 20,000 missing, almost certainly dead too. Another 90,000 had been wounded. But still the attacks continued.

Not all the soldiers had believed Nivelle’s promises of an easy victory and decisive breakthrough. In fact, some companies of men had marched to the front line bleating like sheep, believing they were lambs to the slaughter. It was a warning sign that was carelessly ignored. Chemin des Dames became the place where the morale of the French army finally broke.

Nivelle’s career was over. Already seriously ill with tuberculosis, he would not live to see the end of the war. His replacement was the other hero of Verdun, Pétain. He moved from his post of chief of the French general staff, to become commander-in-chief of the French northern and northeast armies. Pétain had only been in his new job for three days when he received reports of mutinies among front-line soldiers.

The first occurred in the 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment. Out of 600 men, only 200 had survived the Chemin des Dames offensive. After a brief respite behind the French front lines, they were once again ordered back to the trenches. It was the early evening of April 29, 1917. Many of the men were drunk on the cheap red wine that was supplied free, and frequently, to French troops. Almost all refused to return, gathering in large groups and shouting “Down with the war!” But, by early the next morning, the men had sobered up, and marched back to the front line.

As they marched, the officers of the battalion decided this insurrection should be immediately punished. At random, a dozen men were pulled from the ranks and charged with mutiny. Five of them were shot. Another had an amazing escape. As he was being led to the firing squad by a group of guards, a German artillery bombardment fell around them. He ran into nearby woods and was never seen again.

Four days later, another mutiny broke out. This was far more serious as it involved the entire Second Division – thousands of men, almost all drunk and refusing to carry their weapons or go back to the trenches. But, when the drink wore off, most of the men gave in and marched to the Front. The few who still refused to go were quickly arrested, and no one else in the division was singled out for punishment.

It was just the beginning. In early May, this drunken rebellion spread throughout the army. It was an odd sort of mutiny, though. There were no reports of officers being attacked or killed, and no political demands. When officers spoke to the men who had been elected by their comrades to represent them, they were told the soldiers would continue to defend their trenches. It was the attacks against the Germans they were no longer prepared to take part in.

While large-scale mutiny swept the ranks of the French army, extraordinary events were taking place in Russia, where a similarly widespread mutiny had led to the overthrow of the Tsarist government, deeply alarming the other Allies. The French authorities were lucky there were no equivalents of Lenin or Trotsky among their troops; if there had been, the history of France, and Europe, over the course of the 20th century might have been very different. The French rebellion had no obvious leaders and was not being directed by anyone. But, despite this, the mutiny spread so fast that by June, 54 divisions – over half the entire French army on the Western Front – were affected. Some 30,000 men just left their front-line posts and tried to walk home.

The causes of the mutiny were both simple and complicated. In essence, the ordinary French soldier had lost faith in his generals. He was not prepared to lay down his life for a way of fighting he no longer believed in. But there were other causes too, and these were serious enough to make anyone wonder why the mutiny had not happened before.

Compared to their British counterparts, the French soldiers had had to put up with harsher conditions and military discipline. Their pay was miserly. The food they had to eat was often cold and of very poor quality – an especially troubling state of affairs for such a nation of gourmets. The British army, by comparison, made great efforts to keep its trench soldiers supplied with hot food of reasonable quality. British soldiers from the other side of the Channel also spent more time away from the trenches, and with their families, than French soldiers. This was especially painful for the French, as many were fighting less than a day’s train journey away from their homes; but they were rarely offered leave. Although all sides suffered horrendous casualties, of the Allies, the French lost the most men. One in four Frenchmen between the ages of 18 and 30 would die in the war – a million and a half in all, with millions more wounded and maimed for life.

In the French High Command, the mutiny caused a sense of panic. France had already suffered so much – so many men had been sacrificed to keep the German army from overrunning their country. How awful it would be if the French lost the war because their troops had just given up and gone home.

Pétain, as commander-in-chief of the mutinous divisions, was the man who had to sort it all out. Fortunately for France, he chose to address his soldiers’ complaints, rather than simply to suppress the revolt with great brutality. He had three major problems. First, he had to take immediate steps to introduce reforms to make life more bearable for his men, most of whom were conscripts fighting for the duration of the war, rather than career soldiers. Second, in order to uphold discipline in the army, he had to punish those responsible – a difficult task when the mutiny really did seem to be spontaneous and lacking in “ring leaders”. Third, and most important of all, he had to keep the mutiny secret from the Germans. If they knew what was going on, they could break through the French lines and be in Paris within a week. Then the war would be lost for sure.

Several older generals were immediately replaced. The quality of food fed to front-line troops was improved. A system of home leave was introduced, and rest camps behind the front lines were made more habitable. The arrival of Pétain, although it happened just before the mutinies occurred, was a stroke of luck. This veteran French general, already 60 years old in 1917, had a reputation for being careful with the lives of his men. Almost alone among the officers of the French High Command, ordinary soldiers trusted him not to throw away their lives in useless offensives.

Nonetheless, punishment for the mutiny was random and transparently unfair. For example, in early June, a battalion of 700 men under the command of General Emile Taufflieb was marching back to the Front when they all disappeared into a forest at the side of the road. Earlier in the day, word had swept through the troops that there was a vast cave nearby in which they could all hide. Taufflieb, showing commendable bravery, went into the cave and talked to the mutineers. He told them to return to the front by daybreak, or they would all be slaughtered. The men came out. But once they were back under army command, 20 were pulled from the ranks and shot. Taufflieb had neglected to mention this would happen. But, in other divisions, once order had been restored, the momentary mutiny was swiftly forgotten and no one was punished.

In all, perhaps 24,000 men were arrested and put before military courts. Of these, 554 judged to be leaders of the revolt were sentenced to death. But only 45 were shot; the rest were sent to the penal colony of French Guiana – a miserable fate for conscripted soldiers who had fought bravely until they could take no more. Those executed were shot before their comrades, who were then made to file past the dead men. Many more French soldiers were shot at random and without trial, but the number of those deaths is difficult to estimate.

The mutiny was dealt with carefully. But, beneath the concern, there was an iron fist determined that such widespread disobedience would never be allowed to happen again. Among the rebellious divisions was a regiment of Russian soldiers, sent to the Western Front as a goodwill gesture by the ailing Tsarist regime before it was overthrown. These soldiers had endured even worse conditions and even more incompetent leadership than their French and British allies. They were all too ready to follow their rebellious French comrades and mutiny. Their fate was pitiful. The French authorities had had to deal with their own soldiers with some leniency – there were too many to punish, and harsh discipline might have provoked worse rebellions, and even revolution. The Russians, though, were expendable. The regiment was surrounded and blown to pieces by French artillery.

The mutiny had lasted for six weeks. The French army had escaped a crushing defeat by the skin of its teeth. But the soldiers who had rebelled had sent a clear message to their generals. From now on, there would be no more mass attacks; French soldiers would only take part in small-scale assaults on the German lines. And so the horrific bloodletting of the previous three years came to an end. For the rest of the war, the lion’s share of the fighting against the Central Powers would be left to Britain and the Commonwealth, and fresh and enthusiastic American troops, who had entered the war just in time to save the Allies from an almost certain defeat.

Behind the front lines, the government reacted by tightening censorship in the French newspapers and imprisoning those who had campaigned for an end to the war. These days, such people would be called peace campaigners. In 1917, they were called anti-war agitators.

Even now, the mutiny is still a shameful and touchy subject in France. On its 80th anniversary in 1997, the French prime minister, Lionel Jospin, suggested the mutineers needed to be understood and forgiven. This provoked a stern denunciation from the French president, Jacques Chirac. The act of expressing sympathy for those war-weary men was still considered an outrage. But, nowadays, most people would agree that the mutineers deserved pity rather than condemnation. They were, said French politician François Hollande recently, “simply men who got lost in a hell of fire and blood.”