It was October 21, 1939, and World War Two had just begun. In Zutphen, a town in neutral Holland, rain drummed down on the roof of a large Buick limousine. Behind the wheel Sigismund Best adjusted his monocle and squinted through the window of his car. Suddenly another car drew up. A man jumped out. Best leaned over to open the door and the man climbed in beside him. The Buick roared into life and rolled through the streets, wipers flailing.

Best looked like the typical English gentleman. Tall, with an aristocratic manner, he wore spats and a tweed suit. His hair was carefully oiled; he even wore a monocle. But this was deceptive. Best was in fact half Indian. He was also a spy. He lived in Holland with his Dutch wife, and ran a small business importing bicycles, but really he was a member of Z Branch – an independent group of agents which formed part of Britain’s Special Intelligence Service (SIS).

Best’s credentials were impressive. He spoke four languages, and during World War One he had run a successful network of spies behind enemy lines. Currently, he was trying to make contact with dissatisfied Germans willing to fight against Hitler and the Nazis. As far as he could tell, things were going very well indeed.

Best had been contacted some weeks earlier by one of his agents, a refugee who had fled from persecution in Germany. The man knew many high ranking officers within the German army and he had assured Best that there was a great deal of resentment against Hitler, resentment which had built up to a strong resistance movement. Best had probed deeper and had been given the name of an officer involved with the resistance movement – Hauptmann Schaemell. This was the man now sitting in the car with him.

Best spoke German well, and the two men drove through the Dutch countryside chatting together in German about classical music. At the town of Arnhem, they picked up two of Best’s colleagues, an English officer named Major Stevens, and a Dutch officer named Captain Klop. Although Holland was neutral at the time, Klop was assisting the British. He wanted to keep his nationality a secret, so he was pretending to be Canadian and was using the name Coppens. This was a convincing alias. Klop had spent several years living in Canada, and the country was an ally of Britain’s.

Best drove on. Schaemell, he reflected, seemed like a good catch. As they drove, the German reeled off a list of officers who were eager to see Hitler’s downfall and named an important general who was prepared to lead the resistance. Schaemell promised to bring the general to their next meeting, which they set for October 30.

What Best didn’t know was that the Germans were one step ahead of him. The refugee who had introduced him to Schaemell was in fact a German spy named Franz Fischer. The resistance movement Best was hearing all about did not exist. Schaemell himself didn’t exist either. He was really Walter Schellenberg – a 29 year-old ex-lawyer who was now head of German foreign intelligence. Instead of spying for Best, he wanted to annihilate him.

Schellenberg’s plan was simple. Over the coming weeks, he intended to lull the British and Dutch agents into a false sense of security, by pretending to be a willing collaborator. Then he would lure them into meetings, which would enable him to penetrate the SIS and find out about their operations.

First, however, Schellenberg had to convince Best that he was genuinely working against the Nazis. When he returned to Holland from Germany on October 30, he brought with him two army friends. One of the men was silver-haired, with an old-fashioned elegance which made him look as if he might be a disgruntled aristocrat seeking to overthrow the Nazis. It was a plausible disguise – many upper class Germans did regard Hitler as a common upstart.

They crossed the border and drove to Arnhem, where Best had agreed to meet them. But Best was not there. They waited. After three-quarters of an hour, they were about to give up when they saw two figures approaching their car. But these were not the British agents they were expecting. They were Dutch police officers, and they got into Schellenberg’s car and curtly ordered him to drive to the police station.

This was not at all what Schellenberg had been planning. He was meant to be hoodwinking them, and now it looked like they had caught him instead. The head of German foreign intelligence was quite some prize.

There at the station Schellenberg and his army friends were given a thorough going over. Their clothes and luggage were searched from top to bottom, and this was nearly their undoing. In the wash-bag of one of Schellenberg’s accomplices, open on the table ready for inspection, was a small packet of aspirins. Unfortunately for the Germans, these were not any old aspirins. They were a type issued to the SS (Schutzstaffel), the elite Nazi military corps, and bore the official label SS Sanitaetschauptamt (the main medical office of the SS). When Schellenberg spotted the pills, he turned white with alarm.

Thinking quickly, he looked around the room. Fortunately for him, the police officers searching their luggage were preoccupied with another bag. So Schellenberg swiftly snatched the aspirins and swallowed the lot – wrapper and all. The bitter taste was still in his mouth when there was a knock at the door. It was Klop, alias Coppens, Best’s fellow agent. Schellenberg could only fear the worst.

But Klop had come to rescue them. He apologized profusely for the trouble they had been put to. It was all an unfortunate misunderstanding, he assured them. But Schellenberg was no fool. He knew exactly what had been going on. The British and Dutch still suspected them, and this whole exercise had been a test to see if they could expose the Germans. If the police had found anything suspicious, such as the SS aspirins, then they would have been arrested.

Schellenberg himself had an even luckier escape. The paper and silver foil of the aspirin wrapper prevented his stomach from absorbing the drug, which could have seriously damaged his body.

From then on, everything went smoothly for the Germans. They were driven to the SIS headquarters in the Hague, and wined and dined like visiting royalty. The next day, Schellenberg and his friends were given a radio set and a call sign. They were told to keep in contact by radio, and that a future meeting would soon be arranged. They all shook hands and were driven back to the German border.

Over the next few weeks Schellenberg was in daily radio contact with Best’s group. Two more meetings were held, and he now felt confident that they had accepted him as completely genuine.

But then a major fly landed in Schellenberg’s ointment, and flies didn’t come much bigger than Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS. There had been an assassination attempt on Hitler – a bomb had exploded shortly after he had left a Nazi party celebration in Munich. Hitler was convinced the SIS was behind the plot, and wanted Best and his men captured immediately.

Schellenberg protested strongly. This would ruin his carefully thought-out scheme.

“The British are completely fooled,” he pleaded. “Just think of all the information I’ll be able to wheedle out of them.”

But Himmler was curt.

“Now you listen to me. There’s no but, there’s only the Fuhrer’s order, which you will carry out.”

So that was that.

With no option, Schellenberg devised a plan. He had already arranged his next meeting with the British – at Venlo, a small town on the Dutch-German frontier. He now contacted Alfred Naujocks of the SS, and arranged for a squad of twelve SS men to accompany him. Schellenberg met the men for a hurried briefing, and they sped off to the border.

Naujocks, a thuggish character, was known as “the man who started World War Two”. Two months earlier, he and a hand-picked squad of men dressed as Polish soldiers, had staged a fake raid on a German radio station on the German-Polish border. This gave the Nazis the opportunity to claim they had been attacked by the Poles, and an excuse to offer their own people, and the world, for invading Poland, which they wanted to turn into a German colony.

Curiously, Naujocks was not impressed with Schellenberg, and later described him as a “namby-pamby, pasty-faced little man.” He wondered how he would cope with the unquestionably dangerous business they were about to undertake.

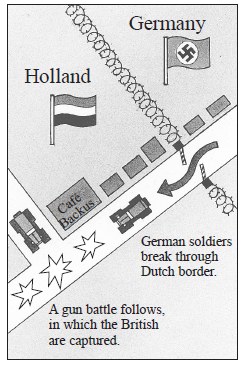

The rendezvous with Best was at two o’clock, at the Café Backus, which was situated in a strange no-man’s land between the German and Dutch frontier posts. Schellenberg was very uneasy and ordered a brandy to steady his nerves.

Finally, at 3:20pm, nearly one and a half hours late, Best’s Buick came into sight. It turned into an alley by the café. Best and Klop got out, and Stevens stayed in the car. Schellenberg walked over as if to greet them, but as he did so shots rang out and a car roared down the street. It was the SS who had been lurking on the other side of the border. They had driven straight over the barrier firing as they went. It broke all the rules of neutrality – Holland was not at war and German soldiers had no right to cross the frontier.

There was instant chaos. Klop drew a pistol and fired at Schellenberg who flung himself to one side. The SS car pulled up at the end of the alley. There were soldiers hanging from its doors and two machine gunners perched on its front fender. Klop ducked and shifted his aim. He fired, then let loose another shot, narrowly missing Naujocks in the front seat of the car. He jumped out and returned fire from behind the open door, while his men scattered for cover, their guns blazing.

Naujocks ran up to Schellenberg and shouted in his face.

“Get out of this! God knows how you haven’t been hit!”

Schellenberg ducked around the corner to avoid the shots and ran head-on into an SS soldier. Unfortunately this man had not been to the briefing and did not recognize Schellenberg. He assumed he was Best, as both men wore a monocle. The soldier grabbed him and stuck a pistol in his face.

“Don’t be stupid,” said Schellenberg, “put that gun away!”

There was a struggle and the SS man pulled the trigger of his gun. Schellenberg grabbed his hand and felt a bullet skim past his head. At that moment Naujocks ran up and told the soldier he’d got the wrong man – for the second time that day he’d probably saved the “namby-pamby” man’s life.

Schellenberg peered around the corner and saw Klop making a break for it. He had been hit and was now trying to get away across the street, the spent shells pumping from his pistol as he fired. But it was no use. A burst of machine gun fire brought him to his knees, and he crumpled into a heap. As he fell, SS men swarmed over to drag Best and Stevens into their car. A couple of them stopped to pick up Klop too, bundling him into their car like a sack of potatoes, but he was already dead. The German cars sped off to their side of the border, with a roar of over-revved engines, burning rubber marks into the asphalt road.

In the moment after they left, a strange silence hung over the scene. Passers-by and border guards emerged from doorways and blockhouses, and stood open-mouthed and motionless. Engine exhaust, burning rubber and the acrid tang of spent bullet cartridges hung in the air. A few pools of red blood stained the road, glistening sickly in the fading autumn afternoon.

The operation had been a huge success for Schellenberg. He had learned much about the methods of the SIS, and had obliterated Z Branch in Holland. A major threat to the Nazis had been put out of operation – and the war was barely two months old.

The Venlo incident was easily the British secret service’s most embarrassing blunder of the entire war, and it had huge repercussions. Hitler used the event to justify the German invasion of Holland in 1940, claiming it proved that the Dutch were not really neutral after all. Furthermore, when Germans who were genuinely opposed to Hitler tried to make contact with British intelligence agents later in the war, they were treated with such suspicion that nothing ever came of their approaches.

Following their capture, Best and Stevens were interrogated at length by the Germans, and gave much away. Stevens was even carrying a list of all the British agents in Holland when he fell into the German trap.

Both men were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp where they remained for the rest of the war. They were freed when the camp was liberated by American soldiers in April 1945. Stevens died in 1965 and Best in 1978.

Schellenberg rose to become the head of Nazi foreign intelligence. After the war he settled in Italy, and died in 1952. Naujocks survived the war too, and died in 1960.