Germany’s secret code, 1941–45

Kapitänleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp peered through the periscope of submarine U-110. It was late in the morning of May 9, 1941, the last day of his life. Through the narrow lens, which surfaced just above the choppy sea south of Iceland, he could see a convoy of British ships bound for Nova Scotia.

Lemp’s wartime service with the German submarine fleet was brief and glorious. In 10 wartime patrols he had sunk 20 ships and damaged another four. Less than a year into the war, and all before he turned 27, he had been presented with the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class, and the Knight’s Cross – among the most prestigious awards available to German military men. This allowed him to be astonishingly insolent with his senior commanders. One instruction from navy headquarters sent to him on his U-boat received a curt two word dismissal: “S***. Lemp”.

The medals, and the tolerance which greeted his outbursts, were a recognition of his calling. It was a wonder anyone, on any side of the war, volunteered to serve on submarines. It was an uncomfortable and highly dangerous life. But the reason they did volunteer was that submarines were devastatingly effective. In the course of the war, German U-boats sank 2,603 cargo ships and 175 of their warship escorts. But for such success they paid a terrible price. More than two out of three U-boats were sunk, taking about 26,000 submariners to the bottom of the sea.

U-boats kept in touch with their headquarters via radio signals. Here they would report their own positions and progress, and receive instructions on where to head next. Such reports were sent in code of course. It was a code that had incessantly perplexed the British. Their intelligence service had set up a special code-breaking department at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, to try to crack it. If the British knew where the U-boats were, or where they were going, they could avoid them or hunt them down. For an island so dependent on food and material brought in by cargo ships, cracking the German navy code became one of the most vital tasks of the war.

On that May morning, Lemp was uneasy. He did not usually carry out daytime attacks, especially on convoys protected by warship escorts. It was far more difficult for such escorts to locate his submarine during a night attack. But his fear of losing contact with his quarry overrode such considerations. Just before noon, U-110 unleashed three torpedoes. Two hit home, sending towering columns of spray into the air by the side of two unlucky ships. But when Lemp ordered a fourth torpedo to be fired, it failed to leave its launch tube.

This minor mishap soon added up to a major disaster for U-110. When a torpedo is fired, water is immediately pumped into the forward ballast tanks, to compensate for the missing weight and keep the submarine level under the water. So, even though the torpedo failed to leave its tube, water still poured into the front of the vessel, unbalancing the submarine. Inside U-110 the crew fought to regain control. During the ensuing disorder, several British warships charged toward the U-boat. Only when Lemp had regained control of his submarine did he check his periscope. Seeing a warship bearing down on him, he immediately decided to dive deeper under the sea – the standard procedure for a submarine under attack. But it was too late. Inside the hull, the crew listened to the dull throbbing of approaching propeller blades. Then came two splashes as a couple of depths charges (heavy canisters loaded with high explosives) were pitched overboard. With dry mouths and an awful tightness in the pit of their stomachs, the crew of U-110 waited for the charges to float down toward them.

When the explosions came with a huge thunderous peal, the submarine rocked to and fro as if caught in a hurricane. The main lights went out, and for a few seconds there was a deathly total darkness. Then, blue emergency lighting flickered on. As their eyes adjusted to the dim light, terrified and disoriented men looked over to their captain for reassurance. Lemp had been under attack before, and he played his part to perfection. Leaning his short, stocky frame casually against his periscope mount, hat pushed to the back of his head, he looked like a suburban bus driver plodding though his usual dreary journey. Lemp’s act had a serious purpose. If anyone on the submarine panicked and started yelling hysterically, the British ships would pick up the noise on their sound detection equipment, and home in on them rapidly.

Now, a deathly hush settled on the submarine, only disturbed by the occasional ominous creaking, and damage reports from other parts of the boat. Neither depth charge had hit the submarine directly, but the damage they caused was still considerable. The trim controls (which kept the submarine level underwater) had broken and the rudder no longer worked. The batteries had been contaminated with seawater and were now giving off poisonous chlorine gas. The depth gauges gave no reading, so it was impossible to tell whether the submarine was rising or falling in the sea. Worst of all, a steady hissing sound indicated that compressed air containers were leaking. Without this air, the submarine would not be able to blow water out of its ballast tanks and get to the surface. Now, even Lemp could not pretend that everything was going to be OK. “All we can do is wait,” he told his men. “I want you all to think of home, or something beautiful.”

These soothing words cannot have been much comfort. In the awful silence that followed, perhaps his crew thought of how their girlfriends or families would greet news of their deaths. More likely than not, in his mind’s eye, each man imagined the submarine sinking slowly into the dark depths of the ocean. If that section of the sea was deep, steel plates on the hull would creak and groan until a fluttering in the ears told the crew the submarine’s air pressure had been disturbed by water pouring inside the ship. Then the boat would be rent apart beneath their feet, and they would be engulfed by a torrent of black icy water. At such a depth, no one aboard had any chance of reaching the surface.

If that section of the sea was shallow, the submarine might simply sink to the bottom. Then, men would have to sit in the strange blue light, or pitch darkness, shivering in the damp cold, as their submarine gradually filled with water. The corrosive smell of chlorine gas would catch in their throats, and they would slowly suffocate in the foul-smelling air.

But just as the men were convinced they were going to die, U-110 began to rock gently to and fro. A huge wave of relief swept through the men. This was a motion the crew all recognized – their submarine was bobbing on the surface. Lemp, still playing his bus driver part, announced, “Last stop! Everyone out!” In a well-rehearsed drill, the crew headed for their exit hatches and poured out on to the deck.

But their troubles were not yet over. As they filled their lungs with fresh sea air, three warships were fast bearing down on them, intending to ram the submarine before it could do more damage. Shells and bullets were whizzing past their ears. But none of the men had any intention of manning the guns on the deck of the U-110, or firing any more torpedoes. They had just stared death in the face, and were desperate to abandon their boat.

Men jumped overboard and drowned, others were killed by the shells and bullets that rained down on them. Amid the wild confusion, one of the ship’s radio operators found Lemp and asked him whether he should destroy the ship’s code books and coding machinery. Lemp shook his head, and gestured impatiently, “The ship’s sinking.” Below deck, the last few left aboard opened valves to flood their submarine, to make sure it really did sink. Then they too jumped into the frothy, freezing sea.

Aboard HMS Bulldog, steaming in to ram the U-110, its captain Commander Joe Baker-Cresswell had a sudden change of heart. When he could see that the members of the enemy crew were throwing themselves off their vessel, he ordered his ship to reverse its engines and it slowly came to a halt.

Other British ships, now certain that the U-110 was no longer a threat, stopped firing. Then, the destroyer Aubretia pulled up nearby to rescue the crew. It had been her depth charges that had done so much damage. As Lemp and a fellow officer struggled to stay afloat, they noticed to their horror that the submarine was not going to sink after all. Clearly something had stopped the water from pouring in. Lemp shouted over that they should try to climb back on board to sink their boat. But, just then, a vast, rolling wave swept over them, and the U-boat was carried out of reach. The crew had missed their chance. Most of the men survived in the water long enough to be picked up. Lemp was not one of them.

From the bridge of HMS Bulldog, Baker-Cresswell surveyed the submarine with great interest. It was floating low in the water, but did not look as if it would sink immediately. Its crew had either been killed or were being rescued. It seemed likely to have been abandoned. So Baker-Cresswell decided to send in a small boarding party to investigate. This unenviable job went to 20-year-old sub-lieutenant David Balme. Together with eight volunteers, Balme clambered aboard a small boat, lowered from the Bulldog, and set off across the choppy sea. As they lurched closer to the U-110’s black hull, Balme grew increasingly tense. As the most senior officer in the boarding party, it was his responsibility to lead his men into the submarine. The only way in was through a hatch in the conning tower. There could be submariners inside, waiting to shoot anyone who entered. Even if no one was still on board, it was standard practice on an abandoned submarine to set off explosives on a timed fuse, or flood the boat, to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. Besides, if the crew had completely abandoned it, it was probably taking in water fast, and could sink at any moment.

So, expecting to die from either a bullet or an explosion, or in a torrent of water, Balme lurched off his boat and onto the slippery deck of the U-110. His men followed immediately after, but no sooner had the last man clambered aboard than a wave picked up their boat and smashed it into pieces on the deck of the submarine. This was not a good omen.

With his heart in his mouth, Balme climbed the conning tower to find an open hatch at the top. It stood before him, the gateway to his doom. Balme fought back his fears and told himself sternly: “Stop thinking… just do it.” He took his pistol from its holster and peered gingerly down into the darkened interior. Immediately, a gust of warm air wafted up to meet him. It contrasted strangely with the icy Icelandic wind blowing off the sea, and would have been inviting had it not smelled so foul. All submarines have a distinct stench. Those not used to it find it almost unbearable. It is the stale dishcloth, rotten cabbage smell of 30 or more men confined for weeks on end in an enclosed, airless environment, unable to bathe properly or clean their clothes.

Balme sensed the impatience of the men behind him. They wouldn’t be the first to be shot, but they were just as vulnerable as he was to explosives or a sinking submarine. “Just do it,” chided a voice in his head. He swung down into the interior, expecting a bullet right through the buttocks. His boots clanged down the long steel ladder, but there was no one there to greet him. He reached the strange blue interior of the control room, and the others briskly followed. As their eyes grew used to the dim light, they blundered through the vessel, searching for any remaining crew.

But U-110 was completely deserted. Quickly Balme’s party began to search the boat for documents, knowing it could still sink or explode at any moment. Their courage was richly rewarded. Inside the radio operator’s cabin was a sealed envelope containing codes and other useful documents, such as signal logs, code instruction procedures, and further code books. But there was also a curious machine that looked like a strange sort of typewriter. It had a keyboard, and one of the men pressed a letter on it. A light on a panel above the keyboard flickered on. The thing was still plugged in! It immediately dawned on Balme that it was a coding machine. Four screws held it to the side of the cabin. These were quickly removed, and the device was carefully put to one side.

It became clear to Balme there must have been complete panic among the crew, to have left everything behind like this. As his search party worked on, the overpowering dread they first felt on entering the boat faded a little. An explosion never came, and neither did the bows of the ship suddenly lurch into the air, throwing them higgledy-piggledy down through the deck sections, just before the U-110 slipped below the waves. But there were other things to worry about. The Bulldog, and other warships guarding the convoy, had gone off to chase other submarines. If the U-110 sank in the meantime, they had no boat, and no immediate chance of rescue.

Finally, Bulldog returned to wait for the boarding party to finish their work. Shortly afterwards, Balme was sitting in the U-boat captain’s cramped cabin. While he ate a sandwich which Baker-Cresswell had thoughtfully sent over, he reflected that life was looking up. When his men had finished their search, a boat was sent to collect them, then a tow rope was attached to U-110. The following morning, in rough seas, the submarine finally sank. Baker-Cresswell was distraught. A captured submarine was quite a prize, and could even have been manned by a British crew and used again. But he needn’t have worried.

News that HMS Bulldog had captured a coding machine from the U-110 caused a sensation at the Admiralty – British naval headquarters. Signals were quickly sent out ordering Baker-Cresswell and his crew to maintain the strictest secrecy. When Bulldog reached the navy base of Scapa Flow in Scotland, two naval intelligence officers immediately came on board, eager to examine the items Balme’s party had seized. What especially thrilled them was the code machine. “We’ve waited the whole war for one of these,” said one. The documents also excited great interest. The next day, as the Bulldog sailed back to its Icelandic patrol, Baker-Cresswell received a thinly veiled message from Dudley Pound, the commander of the Royal Navy. “Hearty Congratulations. The petals of your flower are of rare beauty.”

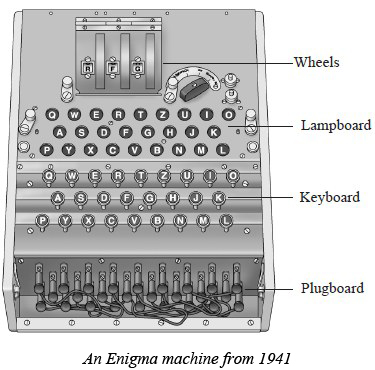

The typewriter-like device Balme’s party had found was a fully-working Enigma machine – the ingenious coding instrument devised by the German military. Enigma was used for “scrambling” a message so that it became diabolically difficult to crack. And there were literally billions of possible combinations for each coded message.

Enigma had a keyboard layout similar to a typewriter, but it only contained the 26 letters of the alphabet. When a letter key was pressed, it sent a signal to a plugboard at the front of the machine. This was also arranged in a standard keyboard layout, with a variable arrangement of cable leads which could go from any direction – say from C to T, and then U to K. This was the first stage in the scrambling of a message.

From the plugboard the signal was then routed to a series of replaceable, interconnected rotating wheels, each with all 26 letters of the alphabet around the rim. These scrambled the original letter still further. There were between three and five of these wheels inside the Enigma, depending on the model. The wheels were chosen from a standard selection of eight.

From the wheels the signal was sent to a “lampboard” positioned behind the keyboard, lighting up another letter which the operator would write down. In this way, messages would be fed through for coding, and then transmitted via Morse code as ordinary radio signals.

Enigma, invented in 1919 by German engineer Arthur Scherbius, was a remarkable machine. Each keystroke, even of the same key, produced a different letter. If the operator pressed three Ps, for example, the rotating wheels could produce three different letters – K, J and F, for example. Even on machines with three wheels, it would not begin to produce the same sequence for the same letter until the key had been pressed 16,900 times. This was when the internal mechanism returned to its original position.

Enigma’s complexity created its own problems. Messages from one machine to another could only be correctly decoded if both machines were set up identically. Each wheel, for example, had to be inserted in one specific position, and in a specific order. Likewise, the front plugboard had to be arranged in exactly the same way.

This created a particular difficulty for the German navy, whose ships and submarines would be away at sea for months on end. They were sent out with code books giving precise details for how their Enigma machine should be set up for each day of the weeks and months ahead, and which settings should be changed at midnight. It was, of course, essential that such codebooks or coding machines should never fall into enemy hands.

The machine captured by Balme, and all the accompanying material, was sent at once to Bletchley Park. This grand mansion and its grounds had been set up as British intelligence’s code-breaking headquarters in 1939, just before the start of the war. Most of the work was done in a makeshift collection of prefabricated huts, with trestle tables and collapsible chairs. It was staffed by some of the greatest mathematical brains in the country. Chief among them was Alan Turing, a Cambridge and Princeton University professor. His ground-breaking work into decoding Enigma messages, using primitive computers, led directly to the kind of computers we all use today.

Turing’s team had a gargantuan task. The Enigma code was complex enough to begin with. But to make it even more difficult, the code was changed every day, and coding procedures were regularly updated. In the course of the war, the Enigma machines themselves also went through several design improvements. On top of all this, at the height of the conflict 2,000 messages a day, from all branches of the German armed forces, were being sent to Bletchley for decoding.

Even with the brightest brains in the country, the staff of Bletchley Park could not crack the Enigma code without some direct assistance. They relied on the kind of lucky breaks David Balme’s boarding party brought them. These came in dribs and drabs throughout the war. Balme’s Enigma machine was not the first to fall into British hands, but it was certainly the most up-to-date. The books and documents he rescued were especially useful. They gave information on settings and procedures for encoding the most sensitive, top-secret information, which the Germans called Offizier codes.

Enigma was like a huge jigsaw puzzle. Any codebooks or machines that were captured helped to put the puzzle together for a few days or weeks, until the codes and machines changed. Then, instead of decoding sensitive and highly useful messages about U-boat positions or air force strikes, code breakers would find themselves churning out reams of meaningless gobbledygook. For the staff at Bletchley Park, such moments provoked heartbreaking disappointment. They were well aware of how their work could save the lives of thousands of people.

In 1997 Balme recalled: “I still wake up at night, fifty-six years later, to find myself going down that ladder.” But, thanks to the courage of men like him, the staff of Bletchley Park were provided with vital further opportunities to break their enemy’s code.