Stauffenberg’s Secret Germany

On a spring morning in 1943, American fighter planes screamed low over a Tunisian coastal road, pouring machine-gun fire onto a column of German army vehicles. Fierce flames bellowed from blazing trucks and smeared the blue desert sky with oily, black smoke. Amid the wreckage on the ground lay Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, one of Germany’s most brilliant soldiers. He was badly wounded, and fighting for his life.

Stauffenberg was quickly transported to a Munich hospital and given the best possible treatment. His left eye, right hand and two fingers from his left hand had been lost in the attack. His legs were so badly damaged that doctors feared he would never walk again.

Willing himself back from the brink of death, Stauffenberg was determined not to be defeated by his injuries. He refused all pain-killing drugs, and learned to dress, bathe and write with his three remaining fingers. His recovery was astounding. Before the summer was over he was demanding to be returned to his regiment.

Hospital staff were amazed by their patient’s stubborn persistence, and admired what they thought was his patriotic determination to return to active service. But it was not to fight for Nazi leader Adolf Hitler that the colonel struggled so hard to recover. What Stauffenberg wanted to do was kill him.

Stauffenberg had supported the Nazis once, but his experience in the war had turned him against them. In Poland, in 1939, he had witnessed SS soldiers killing Jewish women and children by the roadside. While fighting in France in 1940, he had seen a Nazi field commander order the execution of unarmed British prisoners. Worst of all had been Hitler’s war against the Soviet Union (now Russia). Not only had this invasion been fought with great brutality to Russian soldiers and civilians alike, but Stauffenberg had been sickened by Hitler’s incompetent interference in the campaign, and his stubborn refusal to allow exhausted troops in impossible situations to surrender.

After one disastrous battle, Stauffenberg asked a close friend: “Is there no officer in Hitler’s headquarters capable of taking a pistol to the beast?” Lying in his hospital bed, Stauffenberg realized he was just the man for the job.

Like most people, Stauffenberg had his flaws. Although he was untidy in his personal appearance, he was incredibly strict about orderliness and punctuality. He had a ferocious temper, and could become enraged if an aide laid out his uniform less than perfectly. But Stauffenberg was blessed with a magnetic personality and he was a brilliant commander. He also had a sensitive nature, which encouraged fellow officers to confide in him. All these aspects of his character made him an ideal leader of any opposition to Hitler.

As soon as Stauffenberg was well enough to come out of hospital, he was appointed Chief of Staff in the Home Army. The Home Army was a unit of the German Army made up of all soldiers stationed in Germany. It was also responsible for recruitment and training. Stauffenberg quickly established that the deputy commander of the Home Army, General Olbricht, was not a supporter of the Nazis either. He too was willing to help Stauffenberg overthrow Hitler. Between them, they began to persuade other officers to join them.

Stauffenberg and his fellow plotters soon devised an ingenious plan to get rid of Hitler. In the previous year, the Nazis had set up a strategy called Operation Valkyrie, as a precaution against an uprising in Germany against them. If such a revolt broke out, the Home Army had detailed instructions to seize control of all areas of government, and important radio and railway stations, so the rebellion could be quickly put down.

But, rather than protect the Nazis, Stauffenberg and Olbricht intended to use Operation Valkyrie to overthrow them. They planned to kill Hitler and, in the confusion that followed his death, they would set Operation Valkyrie in motion, ordering their soldiers to arrest all Nazi leaders and their chief supporters – especially the SS (elite regiments of Nazi soldiers) and the Gestapo (secret police).

The plot had two great flaws. Firstly, killing Hitler would be difficult, as he was surrounded by bodyguards. Secondly, when the head of the Home Army, General Friedrich Fromm, was approached by the conspirators, he refused to take part. Like everyone in the armed forces, he had sworn an oath of loyalty to Hitler, and he used this as an excuse for not betraying him. Fromm also feared Hitler’s revenge if the plot should fail. Without Fromm’s help, using Valkyrie to overthrow the Nazis would be considerably more difficult.

But the plotters were not deterred and Stauffenberg still threw himself into the task of recruiting allies. He referred to his conspiracy as “Secret Germany” after a poem by his hero, German writer Stefan George. Many officers joined Stauffenberg, but many more wavered. Most were disgusted by the way Hitler was leading the German army but, like Fromm, they felt restrained by their oath of loyalty or feared for their lives if the plot should fail.

The plotters took care to avoid being discovered by the Gestapo. Documents were typed wearing gloves, to avoid leaving fingerprints, on a typewriter that would then be hidden in a cupboard or attic. Stauffenberg memorized and then destroyed written messages, and left not a scrap of solid evidence against himself. And such was his good judgment in recruiting plotters that not a single German officer he approached to join the conspiracy betrayed him.

But by the summer of 1944, time was running out. The Gestapo had begun to suspect a major revolt against Hitler was being planned. They were searching hard for conspirators and the evidence to condemn them. The longer the plotters delayed, the greater their chance of being discovered.

By this time, the plotters had decided the best way to kill Hitler would be with a bomb hidden in a briefcase. As part of his Home Army duties, Stauffenberg attended conferences with the German leader, who thought the colonel was a very glamorous figure and had a high regard for his abilities. Because Stauffenberg had such close contact with Hitler, he volunteered to plant the bomb himself.

In order to give him time to escape, the bomb would be primed with a ten-minute fuse. This device was quite complicated. To activate the bomb, a small glass tube containing acid needed to be broken with a pair of pliers. The acid would eat through a thin steel wire. When this broke, it released a detonator which set off the bomb.

On July 11, Stauffenberg went to Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg in East Prussia for a meeting with Hitler, and two other leading Nazis, Heinrich Himmler and Herman Goring. He hoped to wipe out all three, but when Himmler and Goring did not arrive he decided to wait for a better opportunity.

On July 15, Stauffenberg was again summoned to Rastenburg. On this occasion, Operation Valkyrie was set in motion before the meeting. But unfortunately, at the last moment, Hitler decided not to attend the conference where Stauffenberg was due to plant his bomb. A frantic phone call to Berlin called off Valkyrie and the conspirators covered their tracks by pretending it had been an army exercise.

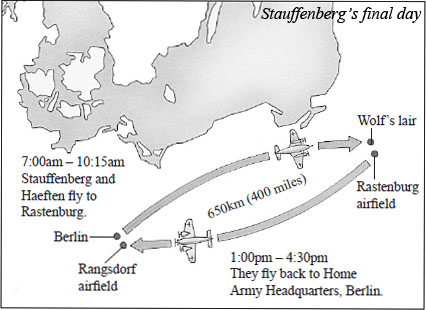

Their chance finally came on July 20, 1944, when Stauffenberg was again summoned to Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg. Together with his personal assistant, Lieutenant Werner von Haeften, he collected two bombs and drove to Rangsdorf airfield south of Berlin, and from there took the three hour flight to Rastenburg.

Arriving in East Prussia at 10:15am, they drove through gloomy forest to Hitler’s headquarters. Surrounded by barbed wire, minefields and checkpoints, the base – fancifully known as “The Wolf’s Lair”– was a collection of concrete bunkers and wooden huts. It was here, cut off from the real world, that Hitler had retreated to wage his final battles of the war.

The conference with Hitler was scheduled for 12:30pm. At 12:15pm, as conference staff began to assemble, Stauffenberg requested permission to wash and change his shirt. It was such a hot day this seemed perfectly reasonable.

An aide ushered him into a nearby washroom, where he was quickly joined by Haeften, and they set about activating the two bombs. Stauffenberg broke the acid tube fuse on one but, as he reached for the second bomb, they were interrupted by a sergeant sent to hurry Stauffenberg, who was now late for the conference.

One bomb would have to do. But there was further bad news. Stauffenberg had hoped the meeting would be held in an underground bunker – a windowless, concrete room where the blast of his bomb would be much more destructive. But instead, he was led to a wooden hut with three large windows. The force of any explosion here would be a lot less effective.

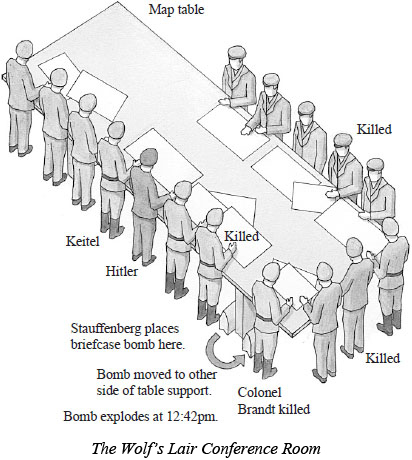

Inside the hut, the conference had already begun. High-ranking officers and their assistants crowded around a large, oak, map table, discussing the progress of the war in Russia. Stauffenberg, whose hearing had been damaged when he was wounded, asked if he could stand near to Hitler so he could hear him properly.

Placing himself to Hitler’s right, Stauffenberg shoved his bulging briefcase under the table, to the left of a large, wooden support. Just then, Field Marshal Keitel, who was one of Hitler’s most loyal generals, suggested that Stauffenberg should deliver his report next. But with less than seven minutes before the bomb would explode, he had no intention of remaining inside the hut. Fortunately, the discussion on the Russian front continued and Stauffenberg made an excuse to leave the room, saying he had to make an urgent phone call to Berlin.

Keitel, already irritated by Stauffenberg’s late arrival, became incensed that he should have the impertinence to leave the conference, and called after him, insisting that he should stay. But Stauffenberg ignored him and hurried off. Like all the conspirators, he hated Keitel, whom he called Lakeitel – a pun on the German word Lakei meaning “toady” or “lackey.”

There were less than five minutes to go. Stauffenberg hurried over to another hut and waited with his friend General Erich Fellgiebel, the chief of signals at the base, who was one of several Rastenburg officers who had joined Stauffenberg’s conspiracy. The seconds dragged by.

Inside the conference room, an officer named Colonel Brandt leaned over the table to get a better look at a map. His foot caught on Stauffenberg’s heavy briefcase, so he picked it up and moved it to the opposite side of the heavy, wooden support. An instant later, at 12:42 precisely, the bomb went off.

At the sound of the explosion, Haeften drove up in a staff car and Stauffenberg leapt in. The two of them had to escape to the airfield quickly, before “The Wolf’s Lair” was sealed off by Hitler’s guards. The hut looked completely devastated and, as they drove away, both felt confident no one inside could have survived.

They were wrong. Brandt and three others had been killed but, in moving the briefcase to the other side of the wooden support, Brandt had shielded Hitler from the full force of the blast. The German leader staggered out of the hut, his hair smoldering and trousers in tatters. He was very much alive.

Fellgiebel watched in horror. Hitler’s death was an essential part of the plot. But, nonetheless, shortly before 1:00pm he sent a message to the War Office in Berlin, confirming the bomb had exploded and ordering Olbricht to set Valkyrie into operation. He made no mention of whether Hitler was alive or dead.

But back in Berlin, Olbricht hesitated because he was uncertain whether Hitler was dead. Until he knew more, he was not prepared to act. Meanwhile Stauffenberg, flying back to Berlin, was cut off from everything. During the two hours he was in the air, he expected his fellow conspirators to be carrying through Operation Valkyrie in a frenzy of activity. In fact, nothing was happening. Unfortunately for the plotters, Stauffenberg could not be in two places at once. He was the best man to carry out the bomb attack in Rastenburg, but he would also have been the best man to direct Operation Valkyrie in Berlin.

At Rastenburg, it did not take long to realize who had planted the bomb. Orders were immediately issued to arrest Stauffenberg at Berlin’s Rangsdorf airfield. But the signals officer responsible for sending this message was also one of the conspirators, and the order was never transmitted.

Only after an hour and a half, at 3:30pm, did the Berlin conspirators reluctantly begin to act. Home Army officers were summoned by Olbricht and told that Hitler was dead and Operation Valkyrie was to be set in motion. But General Fromm was still refusing to cooperate, especially after he phoned Rastenburg and was told by General Keitel that Hitler was alive.

At 4:30pm, the plotters grew bolder and issued orders to the entire German army. Hitler, they declared, was dead. Nazi party leaders were trying to seize power for themselves. The army was to take control of the government immediately, to stop them from doing this.

Stauffenberg arrived back in Berlin soon afterwards. He too was not able to persuade Fromm to join the conspiracy. Instead the commander-in-chief erupted into a foaming tirade against him. Banging his fists on his desk, Fromm demanded that the conspirators be placed under arrest and ordered Stauffenberg to shoot himself. When Fromm began to lunge at his fellow officers, fists flailing, he had to be subdued with a pistol pressed to his stomach. Then he meekly allowed himself to be locked in an office. Other officers at Home Army headquarters who were still loyal to the Nazis were also locked up.

Stauffenberg now began to direct the conspirators with his usual energy and verve. For the rest of the afternoon, they worked with desperate haste to carry out their plan. Stauffenberg spent hours on the phone trying to persuade reluctant or wavering army commanders to support him. He was still convinced Hitler was dead, but many of the people he spoke to would not believe him. At the time, it was widely believed that the Nazi leader employed a double who looked and acted just like him. What if Stauffenberg had killed the double rather than the real Hitler, they thought.

From Paris to Prague, the army attempted to take control and arrest all Nazi officials. In some cities such as Vienna and Paris there were remarkable successes, but in Berlin it was another story. Here, the plotters were foiled by their own decency. They had revolted against the brutality of the Nazi regime and, ironically, only a similar ruthlessness could have saved them. If the conspirators had been prepared to shoot anyone who stood in their way, they might have succeeded.

They failed to capture Berlin’s radio station and army communication bases in the capital. All through the late afternoon, their own commands were constantly contradicted by orders transmitted by commanders loyal to the Nazis.

By early evening it became obvious to Stauffenberg that the plot had failed yet, true to his character, he refused to give up. He insisted that success was just a whisker away and he continued to encourage his fellow plotters not to give up hope. But the end was near.

The War Office was now surrounded by hostile troops loyal to Hitler and, inside the building, a small group of Nazi officers had armed themselves and set out to arrest the conspirators. Shots were fired, Stauffenberg was hit in the shoulder and Fromm was released.

Fromm could only do one thing. Although he had refused to cooperate with the plotters, he had known all about the plot. No doubt the conspirators would confirm this – under torture or of their own free will. Fromm had to cover his tracks. He sentenced Stauffenberg, Haeften, Olbricht and his assistant Colonel Mertz von Quirnheim to immediate execution.

Stauffenberg was bleeding badly from his wound, but seemed indifferent to his death sentence. He insisted the plot was all his doing. His fellow officers had simply been carrying out his orders.

Fromm was having none of this. Just after midnight, the four men were hustled down the stairs to the courtyard outside. By all accounts, they went calmly to their deaths. Lit by the dimmed headlights of a staff car, the four were shot in order of rank. Stauffenberg was second, after Olbricht. An instant before the firing squad cut Stauffenberg down, Haeften, in a brave but pointless gesture, threw himself in front of the bullets. Stauffenberg died moments later, shouting: “Long live our Secret Germany.”

There would have been more executions that night, had not Gestapo chief Kaltenbrunner arrived and put a stop to them. He was far more interested in seeing what could be learned from the conspirators who were still alive.

Still, the Gestapo torturers had been cheated of their greatest prize. Stauffenberg and his fellow martyrs were buried that night in a nearby churchyard. They had failed, but their bravery in the face of such a slim chance of success had been truly heroic.

If Stauffenberg and his conspirators had succeeded with Operation Valkyrie, the war in Europe might have ended much earlier. As it was, it continued for almost another year. In those final months of the Second World War, more people were killed than in the previous five years of fighting.

Hitler described the conspiracy as “a crime unparalleled in German history” and reacted accordingly. Although Stauffenberg, von Haeften, Olbricht and Mertz were dead and buried, Hitler demanded that their bodies be dug up, burned, and the ashes scattered to the wind.

Following brutal interrogation, the main surviving conspirators were hauled before the Nazi courts. They refused to be intimidated, knowing the regime they loathed was teetering on the brink of defeat. General Erich Fellgiebel, who had stood with Stauffenberg as the bomb exploded at Rastenburg, was told by the court president that he was to be hanged. “Hurry with the hanging Mr. President,” he replied, “otherwise you will hang earlier than we.”

Gestapo and SS officers investigated the plot until the last days of the war. Seven thousand arrests were made, and between two and three thousand people were executed. Among them was General Fromm. Although he had never joined the conspirators, he was shot for cowardice in failing to prevent them from carrying out their revolt.

Stauffenberg’s personal magnetism continued to exert an extraordinary influence, even from beyond the grave. SS investigator Georg Kiesel was so in awe of him, he reported to Hitler that his assassin was “a spirit of fire, fascinating and inspiring all who came in touch with him.”