7

Megxitting the Firm: Race, postcolonialism and diversity capital

On 19 May 2018, Prince Harry married Meghan Markle, a bi-racial (her mother is African American, her father white American), divorced, self-identified feminist American actor with a working-class background. Unlike Kate Middleton before her, who is publicly known only through her royal role, Meghan entered the royal family with an already-established media persona. She played the lawyer Rachel Zane in the American cable TV drama Suits between 2011 and 2018, and had small roles in Hollywood films Get Him to the Greek and Remember Me.1 She undertook international charity initiatives, such as an Advocate for the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women; and ran a lifestyle blog, The Tig, and social media accounts on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, giving her a public voice.2

Media and public commentary of Harry and Meghan's wedding seemed to position it as a feminist, post-racial, meritocratic utopia.3 For example, the American civil rights activist Al Sharpton claimed that the wedding showed that white supremacy ‘is on its last breath’,4 and BBC coverage of the wedding ceremony repeatedly referenced a progressive future, as the presenter Richard Bacon claimed, ‘this marriage is going to change the world’.5 Hannah Yelin and I have argued elsewhere that these headlines ‘co-opted’ the Firm into a narrative of progress through Meghan.6 The Sun's headline, for example, read ‘Kisstory: Harry and Meg's historic change for monarchy’, as Meghan's identity was seen to diversify the monarchy and illustrate its progressive values.7 I argued in Chapter 5 that the younger generation of royals have staged a break from the older generation and remodelled themselves as liberal and cosmopolitan, and Harry and Meghan's wedding reflects this process. Indeed, Meghan illustrates how this book has come full circle, and the modernisation of the media monarchy described in Chapter 2 was arguably given new life through Meghan as a royal figure. Her pre-royal career was used in her official biography on the official royal website upon her marriage: for instance her ‘featured quote’ on the website was ‘I am proud to be a woman and a feminist’, and elsewhere it linked to her 2017 opinion piece in Time magazine about the stigmatisation of menstruation and period poverty.8 This language of activism seems to contrast directly with Kate Middleton's ‘featured quote’ about our ‘duty’ to care for children (see Chapter 6), which invests Kate with more traditional feminine values.9 The official royal website highlights what each royal does, and, in including Meghan's pre-royal work on women's issues, I argue that the Firm made its own claim about its investment in these issues. Meghan's pre-royal individual voice is ‘co-opted’ by the Firm for the larger purpose of reproducing the institution.10

Under two years after the wedding, on 8 January 2020, Harry and Meghan announced their intention to ‘step back as “senior” members of the Royal Family’.11 Media and public commentary colloquially referred to this as ‘Megxit’, a portmanteau of Meghan and exit, and a play on ‘Brexit’, referring to Britain's exit from the European Union.12 As I argue, ‘Megxit’ exposes the racialised discourses surrounding Meghan and the Firm, given that Brexit was waged in part through racialised and xenophobic ideologies.13 Indeed, the couple's decision to leave the monarchy was largely blamed on critical, sexist and racist media coverage of Meghan. In the Guardian, the writer Amna Saleem wrote, ‘it didn't take long … for Markle's mere existence to become a tokenistic rhetorical device for those who claimed our country didn't have a problem with race’.14 The writer Afua Hirsch wrote in the New York Times that ‘Black Britons know why Meghan Markle wants out’, citing a universal experience of racism and injustice.15 Despite the suppositions of progress described above, Meghan had been subject to racist media and public commentary since her relationship with Harry was announced in 2016. The right-wing US politician Paul Nehlen tweeted an image of Meghan with the face of the ‘Cheddar Man’ – Britain's oldest complete skeleton discovered to have had Black skin – superimposed on it;16 the right-wing political party UKIP leader Henry Bolton's girlfriend claimed that ‘Meghan's seed will taint our Royal Family’;17 and the Scottish schoolgirl @Hollyynaylorr tweeted ‘unpopular opinion but a black American should not be allowed to marry into a white British royal family’, sparking a backlash culminating in far-right extremist protesters hashtagging #IStandWithHolly.18

The Firm's responses again opened up opportunities for it to appear progressive. In November 2016, Kensington Palace released a statement on behalf of Harry, reading:

The past week has seen a line crossed. His girlfriend, Meghan Markle, has been subject to a wave of abuse and harassment. Some of this has been very public – the smear on the front page of a national newspaper; the racial undertones of comment pieces; and the outright sexism and racism of social media trolls and web article comments.19

I do not dispute Harry's statement. But I argue that, by identifying the media coverage as racist and sexist (what Black feminists would term ‘misogynoir’ to describe the particular intersections of sexism and racism), the monarchy attaches itself to narratives of racial progress.20 This is useful for its image, given the Firm's regressive values on both individual and structural levels: this book has demonstrated the idealisation of bounded national identities (Chapter 3), nostalgia for the landlord/serf model of social order and the romanticisation of imperialism (Chapter 4) and retrogressive gender traditionalism (Chapter 6). The redemption of Prince Harry that I described in Chapter 5 comes full circle in his statement above: a ‘lad’ famous for hedonistic drinking and sex, dressing as a Nazi and using racist slurs, is now calling out the British media and public for racism and sexism. Crucially, the monarchy's historical relationship with racism and sexism goes beyond isolated incidents like Harry's behaviour, or Prince Philip's so-called ‘gaffes’ (see below). I argue it is an institution built on subordinating women's bodies, and systems of slavery, exploitation, extraction, enclosure, colonialism and imperialism. In blaming the media for racist and sexist coverage, and in ‘co-opting’ Meghan's identity to claim its diversity, multiculturalism and relevance, the Firm's own role in reproducing racial, gendered and classed inequalities is obscured.

Harry and Meghan's wedding and subsequent departure from the Firm highlight a series of issues related to this book. I have told a story of radical contextualisation: the Firm is constantly reimagined in relation to socio-political shifts, from changes in capital accumulation to the expansion of media technologies, to varying gender roles. I have argued that representations of the royal family are central to obscuring the Firm's power.

But what happens when an heir to the throne marries a Black celebrity? Representations of Meghan confront the Firm with longer, complex, intersectional histories of racism (post-)colonialism, voice(lessness), servitude, media and celebrity, genealogy, gender, feminism, capital accumulation, social injustice and inequalities. Like ‘Wills and Kate's’ fairy-tale romance as resolution to royal sexual ‘scandals’, I suggest that Harry and Meghan's marriage provides a narrative of resolution to these histories, as the Firm was represented as progressive and inclusive. I argue that the couple's resignation demonstrates that this narrative was too much for the Firm to contain, and representations of Meghan carried too much symbolic weight to resolve those histories. As the critical race scholar Kehinde Andrews argues of the royals, ‘their Whiteness is not a coincidence, it is the point. … Far from Markle's inclusion changing the symbol, she is the exception that proves the rule.’ 21 Similarly, the cultural scholar Sara Ahmed writes, ‘bodies stick out when they are out of place … sticking out from whiteness can thus reconfirm the whiteness of the space’.22 Rather than resolving royal histories, then, representations of Meghan seem to have merely pulled these inequalities into view.

I visited Windsor Park for Harry and Meghan's wedding in May 2018. During the ceremony, I stood amongst the crowd on the Long Walk – which had been decorated with flags and bunting, and included multiple temporary toilets, snack bars, drink bars and ice cream vans – watching one of the large television screens that had been erected for the crowd to view the wedding. I used photography and field-notes to document my experiences, and some of these observations inform the analysis in this chapter.

It is worth reiterating here that I analyse representations of royal figures. Meghan's ‘real’ personality, or her ‘real’ beliefs, are unknown by the media culture representing her and by myself. There are serious issues of voice(lessness) in Meghan's presence in the Firm, and how she seems to have been silenced by the institution itself and in media culture; issues which are especially poignant considering the broader social silencing of women of colour. But my point here is that royal figures serve larger purposes to stage the monarchy. I am interested in how representations of royal figures work alongside, through and in service of the broader structural relations that keep monarchy in place. Or, in Meghan's case, how representations of her may threaten to disturb these structural relations.

‘Megxit is the New Brexit’

On 15 January 2020, a week after Harry and Meghan's resignation announcement, the New York Times published a commentary article by the journalist Mark Landler entitled ‘“Megxit” is the New Brexit in a Britain Split by Age and Politics’.23 Comparisons between the couple's resignation and Britain's exit from the EU had been made throughout the week, with the talks between the Firm and the couple nicknamed the ‘Megxit summit’, like the ‘EU summit’.24 Landler argued that Megxit was ‘resurfacing the same questions that animated the Brexit debate. What kind of society do the British want: open or closed, cosmopolitan or nationalist, progressive or traditional?’ Both debates, he wrote, were waged ‘along political and generational fault lines’: ‘young people and liberals’ more likely to have voted ‘remain’ in the Brexit referendum and more likely to support Harry and Meghan, and ‘older, more conservative people’, who likely voted ‘leave’ and likely supported the Queen.25

Whilst this analysis simplifies Brexit statistics, it neatly exposes the context of Meghan's introduction to the Firm. Meghan appeared as a royal figure at a particularly pertinent time in British history, and responses to her are entangled in wider socio-political debates about race, nation, imperialism and nostalgia. The couple's engagement announcement came eighteen months after Brexit, and their time in the Firm matched Britain's withdrawal period from the European Union: the UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020, and Harry and Meghan left the monarchy on 31 March 2020. Harry and Meghan's UK–US relationship also echoes the UK strengthening its ‘special relationship’ with the US as a potential post-Brexit trading partner. The media scholar Nathalie Weidhase argues that Harry and Meghan's union represents ‘bringing two nations together’, particularly pertinent considering the Firm's role as nationally symbolic.26 At Windsor Park during the wedding, I witnessed multiple references to a UK–US union, from two friends dressed in complementary Union Jack and US flag-patterned suits to multiple US television broadcasters and a contingent of students or alumni from Meghan's former university, Northwestern University, Illinois. BBC coverage stationed one reporter, Richard Bacon, in Meghan's ‘hometown’ of Los Angeles to offer live commentary alongside celebrity guests and people from Meghan's past, such as the principal of her former school.27

Brexit is partly invested in lingering nostalgia for the British Empire, or what the cultural theorist Paul Gilroy calls ‘postcolonial melancholia’.28 The debate to ‘leave’ was waged through a racialised lens, as Sivamohan Valluvan summarises: ‘issues relating to immigration, refugees, Muslims, the spectre of Turkey, the Roma, and the tyranny of political correctness’.29 This occurred alongside increasingly negative media coverage of immigrants and refugees; then Home Secretary Theresa May's promise to ‘create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants’; the ‘Windrush scandal’ where people were wrongly deported from Britain for not meeting citizenship requirements; rising numbers of racist hate crimes; and the election of right-wing, populist governments across the globe, supporting racist and anti-gender policies.30 These growing global far-right movements have prompted expanding social justice protests, seen in Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, and more radical left-wing political organisations, such as Momentum supporting Jeremy Corbyn's leadership of the UK Labour party. In this factional context, left-wing views of, for example, anti-racism and feminism are attacked in right-wing rhetoric for being too ‘politically correct’, or for championing ‘identity politics’, a term that was originally coined by the radical Combahee River Collective to describe intersecting oppression, but which has since become a pejorative term to dismiss social justice movements.31

Meghan quickly became associated with ‘identity politics’ in the British right-wing press. The right-wing populist journalist and commentator Piers Morgan repeatedly attacked Meghan via his Daily Mail column. He used stereotypes associated with the contemporary political factions, including accusing her of ‘playing [the] race card’ (a dismissive term implying that people of colour abuse their oppression to win arguments) and being a ‘whiny spoiled brat’, and referring to ‘Me-Me-Meghan Markle's shamelessly hypocritical super-woke Vogue stunt’ (‘woke’ is a slang term, now used pejoratively, for social justice awareness).32 In the Daily Telegraph, the journalist Sherelle Jacobs referred to Meghan's guest editorship of Vogue magazine (see below) as showcasing the ‘“woke” liberal elite’, a disparaging phrase used to describe left-wingers who are highly educated and affluent.33 Meghan was used as the prototypical ‘leftist’, open to attack – by virtue of her visibility – by racist, xenophobic and anti-gender ideologists. The anti-racist advocacy group Hope Not Hate analysed over five thousand tweets using anti-Meghan hashtags, and found many of these users were also tweeting right-wing, pro-Brexit and pro-Donald Trump hashtags, suggesting an overlapping of concerns.34 Indeed, #Megxit was being used by these accounts to forge connections between Meghan and populist politics long before the couple's announcement to leave the Firm. The language of ‘Megxit’, therefore, is indissoluble from racism, xenophobia and misogyny.

To report the exit agreement between the Firm and the couple, the Sunday Mirror used the headline ‘Queen Orders a Hard Megxit’.35 This plays on language of a ‘hard Brexit’, referring to the plan of some Conservative party MPs (such as the now Prime Minister Boris Johnson) for the UK to leave the EU, the EU's single market and the EU Customs Union. In a ‘hard Brexit’, it is reactionary, populist figures like Johnson who are shoring up the country against ‘unwanted’ immigration and the ‘woke liberal elites’. According to that logic, in a ‘hard Megxit’, it is the Queen shoring up our country against Meghan as an ‘unwanted immigrant’ and a ‘woke liberal elite’. That is, if the Queen represents the conservative ideal, Meghan is the antithesis. The multiple media reports claiming that Meghan had disagreed with Kate arguably play on similar oppositions. The journalist Helen Lewis identifies the Kate versus Meghan reports as a ‘culture war’, where ‘women's lives provide a particularly vivid arena for the clash between traditionalism and modernity’ because they are seen to represent all women.36 If I argue that Kate is seen as representing the right-wing #tradwife (Chapter 6), then Meghan is seen as signifying social progression and ‘wokeness’.

Understanding this context is necessary to understanding responses to Meghan. Her gendered, classed and racialised identity are given meaning through the socio-political context of Britain and beyond, and she came to act as a shorthand for broader political factions. I argue that Meghan was subject to symbolic overload, unable to embody the representational demands put upon her, and instead merely emphasising the inequalities her image supposedly resolved.

Diversity capitalism in the Firm

Two days after Harry and Meghan's son, Archie, was born in May 2019, their Instagram account @sussexroyal published an official photograph of the Queen meeting her great-grandson.37 The photograph, taken at Windsor Castle, features Meghan cradling baby Archie surrounded by Harry, the Queen, Philip and Meghan's mother Doria Ragland. Like other official royal photographs (see Chapter 6), the image blends ‘traditional’ and modern, ordinary and extraordinary. The men wear grey suits, Meghan wears a formal white shirt-dress, Doria a cream dress and gold scarf, and the Queen a casual blue cardigan and skirt. Most notable in this family portrait are markers of racial identity. Doria, Meghan and Archie's presence in official royal portraiture represents a shift from generations of British royal portraits, which have been almost exclusively white. Indeed, the composition of this photograph as an ‘ordinary’, multigenerational and multicultural family arguably invests the Firm with progressive, inclusive and future-oriented values.

This reflects narratives told during Harry and Meghan's wedding. In addition to the media commentary described above, many mixed-race and Black commentators or publics celebrated Harry and Meghan's wedding as representative of inclusivity and progress. Colleen Harris, a former royal aide and one of the first women of colour working in the Firm, wrote that the wedding was ‘the day the monarchy embraced multicultural Britain's future’.38 The broadcaster Afua Hirsch, whose book Brit(ish) critiqued the history of British racism, lauded the wedding as a ‘rousing celebration of blackness’.39 On social media, @MsJillMJones tweeted ‘that was probably, the most diverse … event in the history of The Royals’ and @yemsxo tweeted ‘WHAT A TIME TO BE ALIVE! IM SO HAPPY!’.40

My analysis is not disputing that the wedding was an important symbolic and iconographical moment. Although some historians suggest that Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who married George III in 1761, was Black, having a woman of colour at the centre of British hereditary power is still something rarely represented.41 Fantasies of the Firm as meritocratic, beginning with Diana and then intensifying with ‘commoner’ Kate's class mobility, were invested with new meaning under Meghan. Now, even a Black American with a working-class background can enter the elite British establishment (of course, since then, some media have exposed the limitations of this narrative, as she may enter the establishment but they make clear she is not welcomed, nor does she apparently fit).

If we understand the Firm as a corporation, Meghan's entrance takes on new significance. I have argued in Running the Family Firm how royal figures serve particular purposes to reproduce the institution. Representations of Harry's affable persona makes the Firm appear ‘ordinary’ and distracts from the military-industrial complex, Kate's investment in being a wife and mother reproduce ideologies of conservative, ‘middle-class’, nuclear ‘family values’. Similarly, representations of Meghan can be seen as a form of diversity capitalism, used to extend the Firm's markets through notions of diversity, post-imperialism and post-racialism. The sociologists Celia Lury, Henry Giroux, and Les Back and Vibeke Quaade have each analysed the global clothing retailer Benetton's 1990 campaign ‘The United Colors of Benetton’, which comprised advertisements featuring people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds wearing signifiers of US national identity (for example, stars and stripes to represent the flag) to promote the ‘diversity’ of both the products and the customers.42 Their analyses argued that Benetton tried to produce a new corporate image as a company of diversity and inclusivity, to attract customers with vested interests in social change. That is, racial politics were used to expand Benetton's markets, or what the authors refer to as ‘diversity capitalism’. Similarly, the marketing scholar David Crockett proposes that US advertisers have ‘marketed Blackness’ to make claims about the companies’ progressive values and appeal to broader consumers.43 The media scholar Jennifer Fuller argues that US television cable channels use Blackness as a marketing tool to differentiate themselves from growing competitors.44

There is an important distinction here between notions of ‘diversity’ and notions of ‘difference’. Scholars argue that ‘diversity’ suggests a dilution of identity, where ‘we are all different’ and therefore ‘we are all the same in our difference’.45 There are no dominating groups because we are all equal in our diversity. Diversity is a ‘respectable’ and ‘more palatable’ way to mark identity because it refuses to engage with structural inequalities.46 A politics of ‘difference’, meanwhile, recognises structural inequalities and marks out points of disparity between groups; for example speaking as a woman of colour draws attention to the specific, embodied experiences of being part of this identity group. ‘Difference’ is marked to acknowledge the politics of this difference. Sara Ahmed's work on institutional diversity notes that these definitions mean that ‘diversity’, not ‘difference’, acts as a useful image-maker for organisations wishing to appear as if they are doing ‘good work’.47 Vague references to ‘diversity’ offer a veneer of repairing racialised histories, because they suggest progress without actually attending to the structural inequalities arising from these histories.48 One way to resolve the histories of an institution that has an image problem around race is to co-opt an image of diversity.

‘Diversity capitalism’ builds on ideas of ‘racial capitalism’, which the critical race theorist Cedric Robinson describes as how ‘the development, organization and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions’.49 That is, capital is extracted from processes of invasion, expropriation and hierarchy – all of which are racialised – and classification and racial hierarchy were used to justify colonial pillages, theft and dispossession.50 ‘Diversity capital’ describes how racialisation is used as a tool of differentiation under a guise of progress, but without structural or institutional changes to systems of inequality. The business scholars Janet L. Borgerson and others found that Benetton's ‘operational identity’ failed to live up to its diversity-focused brand identity, whereby its fashion shows and promotional materials had few ethical values beyond casting multicultural models.51 They argue that this created a ‘“hollow” visual identity’, where symbolism outranked deeper meaning.52 The language of diversity is depoliticised, and the inherent whiteness of institutional power remains.

Likewise, the image of the Queen and Philip meeting Archie does little to alter inequalities in the Firm beyond casting a new set of more diverse royal figures. Even the setting of the photograph reproduces the structural inequalities of monarchy. The town of Windsor is home to the prestigious Eton College, an all-boys public boarding school enshrined in systems of class and racial inequality in the UK.53 Windsor Castle was originally built in the eleventh century by William the Conqueror as a motte-and-bailey castle to fortify the building against invasion by other monarchs or overthrow by the public, and hence preserve hereditary royal power. It is now the Queen's ‘weekend home’ – a surplus palace in the monarch's property portfolio. The pastel painting in the background of the photograph of Archie meeting the Queen is Landscape with a Groom and two Horses, and two Peasant Women by the eighteenth-century Italian artist Francesco Zuccarelli. The image depicts inequality and servitude. The term ‘peasant’ refers to a pre-industrial agricultural labourer, and ‘Groom’ is an alternative for ‘stable boy’ – both workers would have typically been very poor and served the wealthy. More broadly, Doria, Meghan and Archie's family history intersects with the monarchy's colonial voyages. According to the journalist Andrew Morton, Doria's first identifiable African American ancestor was Richard Ragland, born in Georgia in 1830.54 The state of Georgia was founded as a British colony in 1733, named after King George II as a symbol of monarchical power. Meghan, Archie and Doria's presence in the Firm does not alter or absolve these histories of inequality and white supremacy. Rather, the group is absorbed into the Firm's narrative of progress.

If we understand representations of Meghan as a form of diversity capital, her royal ‘work’ also gives the Firm access to more diverse markets. In 2019, before ‘stepping back’ from the monarchy, Meghan guest-edited the September edition of British Vogue, a glossy, high-profile, British fashion magazine.55 The edition was headlined ‘Forces for Change’, and Buckingham Palace's press release claimed that it highlights ‘trailblazing change makers, united by their fearlessness in breaking barriers’.56 The cover featured 15 women, including the teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg and the author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, as part of what Meghan called ‘the strength of the collective in the diverse selection of women chosen for the cover’.57 She continued in her introduction, ‘I hope readers feel as inspired as I do, by the forces of change they'll find within these pages’.58 Vogue's editor-in-chief Edward Enninful said of her, ‘to have the county's most influential beacon of change guest edit British Vogue at this time has been an honour’, hence incorporating Meghan into this narrative of activism and transformation.59

Whilst royals have guest-edited magazines before (for example Charles and Country Life) and appeared on Vogue's cover (for example Kate, see Chapter 6), Meghan's edition has a markedly different tone from the conservative, aristocratic versions preceding her. She writes that the cover women were chosen for ‘their commitment to a cause, their fearlessness in breaking barriers’.60 Celebrating women who have a voice and enact change is the opposite of the retrogressive, traditional royal femininities we saw in Chapter 6. And, indeed, it ignores the fact that Meghan's individual voice, previously heard in her blog and social media accounts, has been silenced. The Vogue editorship is part of Meghan's philanthropic ‘work’, undertaken by royal figures to reproduce, and produce consent for, the Firm. The very purpose of this work is to maintain hegemonic norms of monarchical power through ideologies of social responsibility and value. The language of diversity in Vogue is ‘co-opted’ by the Firm to remake itself in a new model of liberal, cosmopolitan and multicultural Britishness, and ensure its survival in a changing socio-political context.61 Ideas of diversity are used here as a form of capital – both symbolic and economic – to serve the Firm. As I have demonstrated throughout Running the Family Firm, the monarchy is always changing in order to stay the same, and representations of Meghan are the latest iteration of this process.

Meghan also gives the Firm access to patronages focusing on women's rights. During her time as a royal, she worked with Smart Works, an organisation providing clothing for unemployed women to attend job interviews, and visited the charity One25, which provides food packages to sex workers in Bristol.62 She published the charity cookery book Together, which featured recipes from the women displaced in the Grenfell Tower fire, who created a temporary communal kitchen to cook for other survivors.63 In her introduction to Together, Meghan repeatedly references the importance of unity and collectivity in responding to the crisis: ‘this is a tale of friendship, and a story of togetherness’.64 As I argue elsewhere, while this may describe the displaced women cooking for their community, when written in an introduction by Meghan who is operating on behalf of the Firm this incorporates the monarchy ‘into narratives of tragedy and resilience’, ‘eras[ing] the realities of inequality, and classed and racialised violence’ in Kensington and Chelsea, and obscuring the monarchy's role in creating the structural conditions of inequality that caused the Grenfell fire in the first place.65

During an official royal visit to South Africa, Harry and Meghan visited the Mbokodo Girls’ Empowerment Program, which provides self-defence training to young girls who have suffered trauma. Meghan spoke to the community, saying:

May I just say that while I am here with my husband as a member of the royal family, I want you to know that for me, I am here as a mother, as a wife, as a woman, as a woman of colour and as your sister.66

In this quotation, which received cheers from the audience, Meghan plays with notions of authenticity. On one hand, she separates herself as an individual ‘mother … wife … woman … woman of colour and … sister’ from the monarchy, laying bare the institutional power of the royal family in her ‘official visit’ role. On the other hand, her authenticity as ‘a mother … a wife … a woman [and] … a woman of colour’ invests the Firm itself with new authenticity. Royal visits have historically had colonialist implications, or, as the Indigenous Australian Studies scholar Holly Randell-Moon argues, ‘perpetuate colonial “ways of seeing”’, through invocations of the white (royal) saviour.67 Raka Shome discusses how Diana became a symbol of white virtue in photographs of, for instance, Diana playing with and caring for Black children in Africa.68 She argues such images construct children of the Global South as unhealthy or deprived, legitimising the white saviour ‘rescuing’ them.69 In comparison, Meghan's reference to herself as a ‘woman of colour’ suggests that she identifies with the women she visits, and can position herself as their ‘sister’. Considering she is ‘working’ for the Firm on this visit, this could in turn make the Firm more able to identify with the women, and works to obscure colonialist tensions.

Meghan's speech in South Africa gestures towards conflicts between her assimilation as a royal and a continued process of ‘othering’. She suggests that there is her role in the royal family, and then there is her role as woman of colour. This reproduces the Firm's whiteness. It also speaks to the politics of diversity capitalism. For institutions to claim diversity, those identified as ‘diverse’ ‘must stay in place as “other”’ so they offer a comparison, and can be celebrated as the ‘diverse’ face (for example, university prospectuses that use images of students of colour to do what Ahmed calls ‘diversity work’).70

There are, however, limitations to what ‘diversity work’ is allowed to look like. People of colour must continue to represent diversity symbolically, Ahmed argues, but also not disrupt the status quo and not address the institutionalisation of whiteness.71 That is, they must appear diverse but their values must assimilate with existing institutional values (see below for how this connects to racialised ‘respectability politics’). Meghan has been accused of not appropriately assimilating into the Firm. Critical commentary of Meghan has used language of ‘othering’ to suggest her presence disturbs traditional monarchical norms; traditions which, through their symbolic importance, are vested in imaginaries of British national identity.72 The Sun, for example, has variously accused her of ‘American Wife Syndrome’ for renovating Frogmore Cottage, said that ‘her extravagant spending’ has offended ‘our frugal Queen’, and called her ‘difficult and demanding’.73 These descriptors draw on stereotypes of the ‘angry Black woman’, which displace and dehumanise in comparison to white ‘normative’ respectability.74 This is a form of ‘misogynoir’.75 The claim that her actions have offended ‘our frugal Queen’ is particularly loaded. In her apparently offending ‘our’ Queen, the Sun makes associated claims that Meghan's actions offend Britain as a whole. She is portrayed as the alien ‘other’, becoming what the sociologist Nirmal Puwar refers to as a ‘space invader’.76 Meghan disrupts the status quo.

This all came to a head upon Meghan and Harry's resignation from the Firm. Much of the commentary blamed Britain's tabloid press for Meghan's desire to leave: the activist Aaron Bastani claimed that the ‘royal couple can't challenge Britain's sick press’, and the journalist Sean O’Grady wrote ‘Meghan and Harry are stepping back because of the press’, reflecting the couple's own statements about press criticism and abuse (see Postscript).77 These discourses depict the British news media as racist (which they are), whilst in turn the Firm looked progressive in comparison. Harry's statements against the media's racism, as described above, were laudable, but arguably gave the Firm a veneer of liberal, tolerant values standing up against traditionalist institutions. Sara Ahmed writes that ‘institutions can “keep their racism” by eliminating those whom they identify as racists’.78 Likewise, the Firm can ‘keep its racism’ by scapegoating other institutions in their place and co-opting an image of diversity. This is not to deny that the British media have been racist towards Meghan. But as the journalist Zoe Williams writes in the Guardian, ‘the royals haven't moved, but the political context in which they are now operating has shifted so far that merely through anti-racist advocacy … they've fetched up on the same team as the socialists’.79 Meghan offered the Firm an opportunity to diversify at a time of global political upheaval, and global elites increasingly invested in far-right political projects (such as the Trumps), with which the Firm risks being associated. Meghan offered the Firm a chance to promote itself to new markets, and tap into new sources of (diversity) capital. Her resignation perhaps demonstrates that this was a marketing ploy too far. It is notable that only since her resignation have we seen more meaningful anti-racist statements and engagement with contemporary anti-racist movements from Meghan, such as a speech in support of Black Lives Matter.80 In contrast, despite there being 450 global Black Lives Matter protests in May–June 2020 to demand justice for George Floyd, a Black American man murdered by a white police officer, the Firm has yet to offer any concrete, visible gestures of support. The Firm's apparent refusal to engage with a politics of ‘difference’ in favour of a more palatable ‘diversity’, reveals the limits to the institution's progressive values.

Post-racial imaginaries

The MP David Lammy hailed Harry and Meghan's wedding as ‘Britain's Obama moment’ because he believed it symbolised racial progress.81 An alternative interpretation of it being ‘Britain's Obama moment’ is that it has comparable representations of post-racialism.82 The royal wedding was not automatically progressive because a white, elite man married a woman of colour (nor, indeed, was it automatically feminist because Meghan self-identifies as one). As Raka Shome writes, ‘cosmopolitanism is not colourful global identity politics’.83 What matters is the social, political and cultural context of the wedding, and how the marriage prompts, or does not prompt, structural social change.

The sentiment of those commentators celebrating Harry and Meghan as changing UK race relations reflects the ‘post-racial’. The critical race scholar David Theo Goldberg defines post-raciality as ‘the claim that we are, or are close to, or ought to be living outside of debilitating racial reference’, whereby ‘key conditions of social life are less and less now predicated on racial preferences, choices and resources’.84 That is, race is no longer a deciding factor in people's life trajectory because we have overcome such inequalities. Goldberg identifies Barack Obama's election as the first Black US president as central to the emergence of post-racial ideologies. It was seen to represent the breaking-down of racial barriers, yet, despite these suppositions, structural racism continues to underpin US society. Similarly, the sociologist Remi Joseph-Salisbury discusses post-race as the individualisation of race, whereby structural and historical racism is overlooked in favour of individual achievements (again, Obama is a good example).85 The critical race scholar Alana Lentin compares the post-racial to the politics of ‘diversity’ as I described above, where both homogenise difference and obscure structural inequalities and intersectional experiences of difference.86

Meghan's individual presence as a woman of colour in an institution that has been almost exclusively white is symbolically and representationally notable. For people of colour to see themselves represented in an elite institution, particularly one symbolic of national identity, is extremely valuable. But this assumes that visibility equals power. Meghan's presence does not erase histories of racism in Britain, nor does it absolve the ongoing racial inequalities in the present. Rather, in the spirit of the post-racial, her individual progress as a visibly racialised person in an elite position is celebrated at the expense of structural changes. Both Britain and the monarchy are seen as ‘post-race’ because they have co-opted an image of diversity. Yet, to describe either as ‘post-racial’ is absurd. Indeed, I have contextualised Harry and Meghan's wedding in a period of xenophobic messages on which part of the Brexit vote was waged, and other racialised injustices such as the ‘Windrush scandal’ and the Grenfell Tower fire, all of which demonstrate how institutionalised racism continues to structure British society.

Likewise, reactions to Meghan from the Firm and the British media demonstrate that representations of progress do not necessarily correspond to their values. The plethora of media commentary focusing on Meghan's ancestry and genealogy, usually written as pieces about ‘diversity’ in the monarchy, evidences an ongoing racialised concern with royal blood purity. As the sociologist Ben Carrington points out, notions of the royals having a distinct blood category – ‘blue blood’ – are classed and racialised metaphors referring to someone with such pale skin that blood vessels were visible underneath, and therefore they did not work in the fields where the sun would darken skin.87 Prior to Harry and Meghan's engagement, the Daily Mail reported that ‘Harry's girl is (almost) Straight Outta Compton’, drawing on racist stereotypes of Black urban poverty.88 A few weeks later, an article entitled ‘How in 150 years, Meghan Markle's family went from cotton slaves to royalty via freedom in the US Civil War’, detailed a family tree to ‘track’ Meghan's family history.89 Although they created a similar family tree for Kate (see Chapter 6), for Meghan it was her relatives’ racial profiles that were emphasised, and many included descriptors of her relatives’ race, such as ‘recorded as “coloured”’, which essentialises race. 90 Royal family trees are recreated over time to illustrate dynasty and legitimacy to rule. The Daily Mail's version of Meghan's ‘alternative’ family tree reasserts the white royal bloodline by marking Meghan through her race. It seeks to illustrate not the continuation of the dynasty like the royal version does but rather a classed and racialised meritocracy of ‘rising above’ her history. For example, referring to Meghan's great-great-great-grandmother Mattie Turnipseed, they assert there is a ‘colossal gulf separating the most powerful woman in the world from a young, uneducated, “coloured” woman without a vote’.91 It is Meghan's distance from, and ability to overcome, these histories that is celebrated. The journalist Rachel Johnson (sister of the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson) used colonialist language in the Daily Mail to suggest that ‘the Windsors will thicken their watery, thin blue blood and Spencer pale skin and ginger hair with some rich and exotic DNA’, but added ‘genetically, she [Meghan] is blessed’, perhaps because her lighter skin and physical appearance meets white, Western beauty standards.92 This makes Meghan an ‘acceptable’ face of diversity.93 She is ‘just exotic enough’. The sociologist Maxine Leeds Craig calls this ‘pigmentocracy’, whereby racial hierarchies favour people of colour with lighter skin.94 I argue that Johnson's mixing of the language of ‘pigmentocracy’ with discussions about DNA creates a hierarchical genealogy, where Meghan is seemingly accepted because she is light-skinned and has moved beyond her family's ‘difficult’ history.

Harry and Meghan's wedding ceremony was understood by some as anti-racist, or, as Afua Hirsch called it, a ‘rousing celebration of Blackness’. 95 The African American bishop Michael Curry referenced Martin Luther King and slavery, the ceremony included a gospel choir singing ‘Stand by Me’ which is an anthem from the Black Civil Rights movement and the Black British cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason performed. Again, these are important representational moments. To highlight Black culture at a royal ceremony, which is steeped in histories of British national identity, is remarkable. Yet, as the sociologist Stefanie Boulila argues, the sermon referenced only American anti-racism, and so ‘race and racism were mobilised solely in relation to a past or with reference to an “elsewhere”’, ignoring (not resolving) the specificities of structural racisms in Britain.96 Public responses to the ceremony also demonstrate varying engagement with Black culture. At Windsor Park, I observed people who had previously demanded fellow viewers be quiet as Harry and Meghan declared their vows actively ignoring Curry's address and commenting ‘he goes on a bit’, ‘who invited him?’ and, towards the end, beginning to boo. Later, a man told his companion, ‘I didn't like that Muslim preacher’, conflating two religions and incorrectly identifying Islam as a race. He essentialised and conflated skin colour and religion, where whiteness equals Christianity and people of colour equal Muslim, which reflects the essentialised, racist rhetoric of the Brexit vote. These responses demonstrate that, although the symbol of a multicultural monarchy appeals to some viewers, the reality of this experience provokes criticism (and, indeed, confusion for those who essentialise identity along racialised lines).

Figures in the Firm have also been publicly racist. Prince Philip was infamous for making racist comments during royal tours and visits.97 These comments were widely reported in the British media, yet, as the scholar Hamid Dabashi argues, were often described as ‘gaffes’, which trivialises and dismisses racism.98 The BBC, for example, recounted Philip's ‘memorable one-liners that can make some people chuckle and others cringe’.99 By the BBC not identifying and critiquing racism, the potential harm he caused is dismissed. Other royals have been more explicitly criticised for racism, including Harry as described above. Princess Michael of Kent wore a blackamoor brooch to the Queen's Christmas lunch at Buckingham Palace, the first time she met Meghan. She apologised for ‘causing offence’ after media and public critique.100

There are issues here in individualising racism in the Firm. By making racism the problem of individual royals, the monarchy's history as a racist, patriarchal, imperial institution is masked, as is the effect of this institutional whiteness on British citizens, who are meant to be represented by the monarch(y). In Michael Billig's interviews with British families about the royals in the late 1980s, he describes one incident where a white family were discussing Prince Charles's choice of brides: ‘the younger son then raised the issue of race. [They said that] Prince Charles would not have been free to marry a black girl. In the exchange which followed, there was … joking and … laughter.’ 101 As he outlines, the family's ‘humorous’ exchange made clear that they thought the idea of Charles marrying a woman of colour, and more specifically someone Black, was ludicrous. As with Philip's comments, the joke format here is key. The family police the boundaries of whiteness in the monarchy (although the word ‘white’ was never explicitly mentioned), while denying their own racism through humour.

This family also repeatedly referred to a mystical ‘they’: ‘they don't allow them [the royals] to marry into different religions’.102 ‘They’ are unidentifiable, yet they are attributed power. If the Firm is understood as an institution – or a corporation – the ‘they’ referenced here could refer to the institution as a whole. Sara Ahmed argues that ‘it is important that we do not reify institutions by presuming they are simply given … rather, institutions become given, as an effect of the repetition of the decisions made over time’.103 The cryptic ‘they’ obscures the responsibility of the institution, and those working for it, for shaping the institution's values. The Firm's shaping as a white racial institution has ‘become given’ through much broader histories of empire, colonialism and imperialism. The monarchy supported colonisation projects across the British Empire by granting Royal Charters, funding trade voyages and signifying their ownership of slaves with branding. They continue to extract value from goods stolen during colonisation, such as the Koh-i-Noor diamond.104 The British monarchy as we know it would not exist without histories of extraction and exploitation. The monarchy also operated symbolically as Empire's figurehead. This is, as the English Literature scholar Diane Roberts argues, vested in politicised notions of the royals as idealised white subjects. During the period of Britain's initial colonial voyages and increasingly multicultural population, Elizabeth I emphasised her white skin by painting it lighter to ‘underscore … her difference, her elevation, in whiteness’.105 Victoria was described as ‘the whitest woman in the world’ due to her ‘pale-skinned, white-haired, pearl-draped’ image featuring on stamps, money, memorabilia and portraiture across the Empire.106 Royals have served as symbols of institutionalised whiteness for hundreds of years, used as ‘evidence’ of white superiority and right to rule.

Those discourses claiming that Meghan's introduction to the Firm ‘will change the world’ were tasking one woman with restructuring centuries’ worth of exploitation and violence.107 Stuart Hall identifies this as the ‘burden of representation’, whereby Black people, for example, are expected to speak for the entire Black race because they are seen to represent the communities’ views.108 This homogenises diverse groups on account of their racial identity, and fails to recognise politics of difference. Critical race theory describes whiteness as ‘unmarked’, because it is expected and assumed.109 Meghan stood out as visibly raced in a white, unmarked institution. Her body did not ‘fit’ alongside those white royal figures in the Firm, nor, indeed, in the nation state imagined as white. As such, Meghan was marked from the beginning. Whilst her identity may have been intended to resolve the royals’ problematic histories of race, her marked status meant it was difficult to absorb her into the institutional narrative. Rather than smoothing over stories of Princess Michael of Kent wearing a blackamoor brooch, for example, Meghan's presence (rightly) emphasised the racism. Remarks previously dismissed as ‘gaffes’ were invested with more urgency. The symbolism of Meghan, as a woman of colour confronting the Firm with its racist histories, was too much to contain.

Class, race and respectability politics

At the time of Harry and Meghan's wedding, media representations of Meghan's family had resonances with those of the Middleton family during Kate and William's wedding, and Kate's classed ascent into the royal family (see Chapter 6). The aforementioned interest in Meghan's family tree, for example, used terms of classed and racialised meritocracy. Many of these pieces entirely erased Meghan's self-made wealth and high-profile career. Headlines such as ‘How in 150 years, Meghan Markle's family went from cotton slaves to royalty’ jump 150 years to create a binary of slavery to royalty, ignoring everything between.110 Whilst Kate's classed ascent was complicated by her parent's wealth, Meghan was a multi-millionaire of her own making, yet this narrative was rewritten to emphasise her as meritocratic by marriage, hence erasing her previous achievements and reinscribing traditional femininities.111

At the same time, and again resonating with Kate, some media texts continued to emphasise and disparage Meghan's working-class background. The Daily Mail, in particular, represented her family in ways reminiscent of ‘white trash’ discourses – an American slur, equivalent to the UK's ‘chav’, for an abject working-class figure.112 As the sociologist Matt Wray writes, intersectionality means that whiteness is coded differently according to other identity markers, such as class, gender and sexuality, which creates hierarchies of whiteness.113 Meghan's father, Thomas Markle, was persistently featured in the British tabloid media, culminating in an exposé in the Mail on Sunday about how ‘Meghan's Dad staged photos with the paparazzi’ for profit while the ‘Palace pleaded for privacy’.114 Meghan's nephew owns a cannabis farm in Oregon, USA, and sold the product under the name ‘Markle's Sparkle’, but has denied any association with Meghan.115 The Daily Mail reported on Meghan's aunt and cousin, who had spent the royal wedding in a Burger King in Florida wearing the cardboard crowns produced by the food chain as promotion. The Daily Mail wrote, ‘at exactly the time the Markles hit Burger King in Sanford, 4,300 miles away in Windsor the new Duke and Duchess of Sussex and their 600 guests were being hosted by the Queen in St George's Hall, Windsor’.116 This creates clear class distinctions between Meghan's ‘past’ and ‘future’, positioning her family as objects of mockery and disparagement. The fast-food chain Burger King, associated with working-class stereotypes, provides contrast through its monarchical-themed name to the meal at Windsor, which is coded as upper-class and aspirational. As with her ancestors, it is Meghan's distance from these relations that is celebrated.

The only close relation of Meghan's to attend the wedding was her mother, Doria, and Doria has since been visible at some royal events. The film scholar Fiona Handyside has discussed how representations of Doria reflect the post-racial, whereby she was frequently described in terms such as ‘elegance; glow; grace; poise’, usually associated with white motherhood.117 Doria's coding as white, and Meghan's working-class family's coding as outside the boundaries of whiteness, demonstrate that what is actually being lauded here is individualised behaviour, and how this behaviour adheres to white, upper- or middle-class (and cis-gender) norms.

This individualisation has been referred to as a politics of ‘respectability’. Beverley Skeggs described how white working-class women are subjected to intense surveillance according to codes of ‘respectability’, usually organised around feminised markers of taste and propriety.118 Meanwhile, Black studies scholars such as Brittney Cooper have referred to the proscription of the actions of people of colour as ‘respectability politics’.119 Racial uplift is undertaken through observing white, middle-class norms, including being ‘mainstream, articulate, and clean-cut, black but not too black, friendly, upbeat, and accommodating’.120 This creates a hierarchy of ‘good blacks’ and ‘more problematic black others’, designated along intersectional lines of race, class, gender and sexuality.121

Meghan's classed respectability (because she differs from her working-class family) and investment in structures of neoliberal ideology (for example, her language of ‘empowerment’ for women) ensures that she adheres to ideals of respectable Black femininity.122 The sociologist Enid Logan writes about categories of the ‘model minority, racialised in contradistinction to both the black poor and to traditional civil rights leaders and organisations’.123 Likewise, in research on race and class in Brazil, the sociologist Luisa Farah Schwartzman interrogates the phrase ‘money whitens’ to consider how socio-economic status intersects with the construction of racial identity, speaking similarly to how respectability politics structures access and inclusion.124

The intersections of class, race, gender and sexuality mean that some individuals experience ‘racial transcendence’, and are no longer shaped by their racial profile. Discussing Oprah Winfrey's ‘racial transcendence’, Harwood K. McClerking and others argue that Winfrey had transcended Blackness by minimising her race and rejecting Black activism, becoming equally popular amongst Black and white viewers (we could read this as Winfrey being ‘post-racial’).125 But when she publicly endorsed Obama as presidential candidate, her popularity weakened. This, they argue, demonstrates how racial transcendence is ‘fleeting and fragile’ when ‘popular figures enter a realm far different than the realm where the aura of transcendence was generated’ (in Winfrey's case, entertainment to politics).126 For Meghan, as a celebrity she could be racially mobile. Yet, as the Firm is an institution invested in, and indeed built on, the reproduction of whiteness, this was much more difficult. Money did not ‘whiten’, and Meghan's body remained ‘out of place’ and marked.127

Conclusion

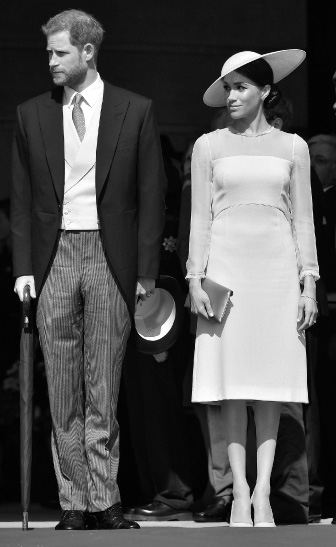

On her first post-wedding royal engagement in May 2018 at Prince Charles's seventieth birthday party, Meghan wore a mid-length beige dress with chiffon sleeves, formal beige hat, mid-heel beige heels and beige ‘nude’ tights (Figure 7.1). This marked a shift from her pre-royal styling, which often included bolder colours, shorter hemlines and short sleeves. The ‘nude’ tights, in particular, drew attention on social media. The garment made her, as Tweeter @HannahFlint claims, ‘officially a Royal’ as they are typical of royal women's styling of modest, conservative, ‘respectable’ femininity.128 Meghan wearing them on her first post-wedding engagement indicates an attempt to remodel Meghan as an idealised royal bride. However, this ideal royal bride is white. As multiple social media commenters pointed out, the tights were ‘paler than her own skin tone’.129 While this illustrates the inherent white privilege in the available shades of ‘skin-coloured’ clothing and accessories, it also demonstrates how Meghan did not ‘fit’ the descriptor of the royal bride.130 Whilst Kate could be contained as a British, ‘middle-class’, white woman with little background, Meghan cannot be contained in the same way. If Kate is a static ‘mannequin’ royal bride, as Hilary Mantel claimed, Meghan is too animated – by virtue of her identity – to be moulded in the same way.131 She cannot be ‘beiged’ with nude-coloured tights, or absorbed into developed histories of institutional power, because her very identity draws attention to the beige tights and to the inequalities in the Firm. As Sara Ahmed writes, ‘adding color to the white face of the organization confirms the whiteness of that face’.132 Meghan is too symbolically loaded to do the work of obscuring unequal histories – work that is required by the Firm's members to ensure the institution's reproduction.

7.1 Meghan Markle, with her husband Prince Harry, at Prince Charles's birthday party, 2019

Despite suppositions of Meghan representing progress, we have seen how Meghan's classed and racialised meritocracy does not equal equality or social justice. Rather, the politics of ‘difference’ are obscured under vague, depoliticised notions of ‘diversity’. Moreover, attempts to absorb Meghan into the Firm are attempts to tap into new markets and appear progressive, diverse and liberal; all of which are part of producing consent for the reproduction of monarchical power in a period punctuated by factional political ideologies and growing global inequalities. As Running the Family Firm has, I hope, demonstrated, any form of feminist, anti-racist agenda Meghan is represented as promoting can be fulfilled only through abolishing the British monarchy and the class system it upholds, and reparations to those countries affected by colonialism, imperialism and enslavement. Even in their resignation letter, Harry and Meghan promised to ‘continu[e] to fully support Her Majesty’.133 They might have left, but (at the time of writing) they have made no attempts to dismantle the institution. Indeed, they continue to benefit from the systems of inequality and privilege that monarchy affords them.