Chapter 4: Planning Ahead for a Solid Presentation

In This Chapter

Constructing a presentation from the ground up

Constructing a presentation from the ground up

Choosing a look for your presentation

Choosing a look for your presentation

Showing your presentation

Showing your presentation

As nice as PowerPoint is, it has its detractors. If the software isn’t used properly, it can come between the speaker and the audience. In an article in the May 28, 2001, New Yorker titled “Absolute PowerPoint: Can a Software Package Edit Our Thoughts?” Ian Parker argued that PowerPoint may actually be more of a hindrance than a help in communicating. PowerPoint, Parker wrote, is “a social instrument, turning middle managers into bullet-point dandies.” The software, he added, “has a private, interior influence. It edits ideas. . . . It helps you make a case, but also makes its own case about how to organize information, how to look at the world.”

I think complaints about PowerPoint should be directed not at the software, but at the people who use it. Many presenters fail to take advantage of PowerPoint’s creative opportunities. They treat PowerPoint as a speaker’s aid or crutch that they can lean on to take away some of the burdens of public speaking. They don’t understand that PowerPoint is a medium, a method of communicating with people using visuals, animation, and even sound.

This chapter explores how you can take advantage of PowerPoint’s creative opportunities. It explains how to build a persuasive presentation and what to consider when you design a presentation’s look. You will also find tips for connecting with your audience.

Want to see a great example of a bad PowerPoint presentation? Try visiting the Gettysburg PowerPoint Presentation, a rendering of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in PowerPoint. Yikes! You’ll find it here:

Formulating Your Presentation

Before you create any slides, think about what you want to communicate to your audience. Your goal is not to dazzle the audience with your PowerPoint skills, but communicate something — a company policy, the merits of a product, the virtues of a strategic plan. Your goal is to bring the audience around to your side.

To that end, the following pages offer practical advice for taking your presentation from the drawing-board stage to the next stage, the one in which you actually start creating slides.

Start by writing the text

I suspect that people actually enjoy doodling with PowerPoint slides because it distracts them from focusing on what really matters in a presentation — that is, what’s meant to be communicated. Building an argument is hard work. People who can afford it pay lawyers and ghostwriters to do the job for them. Building an argument requires thinking long and hard about your topic, putting yourself in the place of an audience member who doesn’t know the topic as well as you, and convincing the audience member that you’re right. You can do this hard work better in Word, where the carnival atmosphere of PowerPoint isn’t there to distract you.

Make clear what the presentation is about

In the early going, state very clearly what your presentation is about and what you intend to prove with your presentation. In other words, state the conclusion at the beginning as well as the end. This way, your audience will know exactly what you are driving at and be able to judge your presentation according to how well you build your case.

Start from the conclusion

Try writing the end of the presentation first. A presentation is supposed to build to a rousing conclusion. By writing the end first, you have a target to shoot for. You can make the entire presentation service its conclusion, the point at which your audience says, “Ah-ha! She’s right.”

Personalize the presentation

Make the presentation a personal one. Tell the audience what your personal reason for being there is or why you work for the company you work for. Knowing that you have a personal stake in the presentation, the audience is more likely to trust you. The audience will understand that you’re not a spokesperson, but a speaker — someone who has come before them to make a case for something that you believe in.

Tell a story

Include anecdotes in the presentation. Everybody loves a pertinent and well-delivered story. This piece of advice is akin to the previous one about personalizing your presentation. Typically, a story illustrates a problem for people and how people solve the problem. Even if your presentation concerns technology or an abstract subject, make it about people. “The people in Shaker Heights needed faster Internet access,” not “the data switches in Shaker Heights just weren’t performing fast enough.”

Assemble the content

Finally, for a bit of practical advice, assemble the content before you begin creating your presentation. Gather together everything you need to make your case — photographs, facts, data, quotations. By so doing, you can have at your fingertips everything you need to get going. You don’t have to interrupt your work to get more material, and having all the material on hand will help you formulate your case better.

Designing Your Presentation

Entire books have been written about how to design a PowerPoint presentation. I’ve read three or four. However, designing a high-quality presentation comes down to observing a few simple rules. These pages explain what those rules are.

Keep it simple

PowerPoint is loaded down with all kinds of features that fall in the “bells and whistles” category. You can “animate” slides and make slide items fly onto the screen. You can play sounds as slides leave the screen. You can make slide elements spin and flash. Sometimes, however, these fancy features are a distraction. They draw the attention of the audience to PowerPoint itself, not to the information or ideas you want to impart.

To make sure that PowerPoint doesn’t upstage you, keep it simple. Make use of the PowerPoint features, but do so judiciously. An animation in the right place at the right time can serve a valuable purpose. It can highlight an important part of a presentation or jolt the audience awake. But stuffing a presentation with too many gizmos turns a presentation into a carnival sideshow and distracts from your message.

On the subject of keeping it simple, slides are easier on the eyes if they aren’t crowded. A cramped slide with too many words and pictures can cause claustrophobia. Leave some empty space on a slide so that the audience can see and read the slide better.

Studying others’ presentations by starting at Google

How would you like to look at others’ presentations to get ideas for your presentation? Starting at Google.com, you can search for PowerPoint presentations, find one that interests you, download it to your computer, open it, and have a look. Follow these steps to search online for PowerPoint presentations and land one on your computer:

1. Open your Web browser.

2. Go to Google at this address: www.google.com.

3. Click the Advanced Search link.

You land on the Advanced Search page.

4. Open the File Format drop-down list and choose Microsoft PowerPoint (.ppt).

5. In the With all of the Words text box, enter a descriptive term that describes the kind of PowerPoint presentations you’re interested in.

For example, enter marketing if you have been charged with creating a PowerPoint presentation about marketing a product.

6. Click the Google Search button.

In the search results, you see a list of PowerPoint presentations.

7. Find and click the name of a presentation that looks interesting.

You see the File Download dialog box.

8. Click the Save button, and in the Save As dialog box, select a folder for storing the presentation and click the Save button.

In a moment, the presentation you selected is copied to your computer. Run a virus check on the presentation to make sure it’s safe to open, and then open it if it doesn’t contain a virus. Do you like what you see? Scroll through the slides to find out how someone else designed a presentation.

Be consistent from slide to slide

PowerPoint offers master styles and master slides to make sure slides are consistent with one another. Master styles and slides are explained in Book II, Chapter 3.

Choose colors that help communicate your message

The color choices you make for your presentation say as much about what you want to communicate as the words and graphics do. Colors set the tone. They tell the audience right away what your presentation is. A loud presentation with a black background and red text conveys excitement; a light-blue background conveys peace and quiet. Use your intuition to think of color combinations that say what you want your presentation to say.

When fashioning a design, consider the audience

Consider who will view your presentation, and tailor the presentation design to your audience’s expectations. The slide design sets the tone and tells the audience in the form of colors and fonts what your presentation is all about. A presentation to the American Casketmakers Association calls for a mute, quiet design; a presentation to the Cheerleaders of Tomorrow calls for something bright and splashy; a presentation about a daycare center requires light blues and pinks, the traditional little-boys and little-girls colors. Choosing colors for your presentation is that much easier if you consider the audience.

Beware the bullet point

Terse bullet points have their place in a presentation, but if you put them there strictly to remind yourself what to say next, you are doing your audience a disfavor. An overabundance of bullet points can cause drowsiness. They can be a distraction. The audience skims the bullets when it should be attending to your voice and the case you’re making.

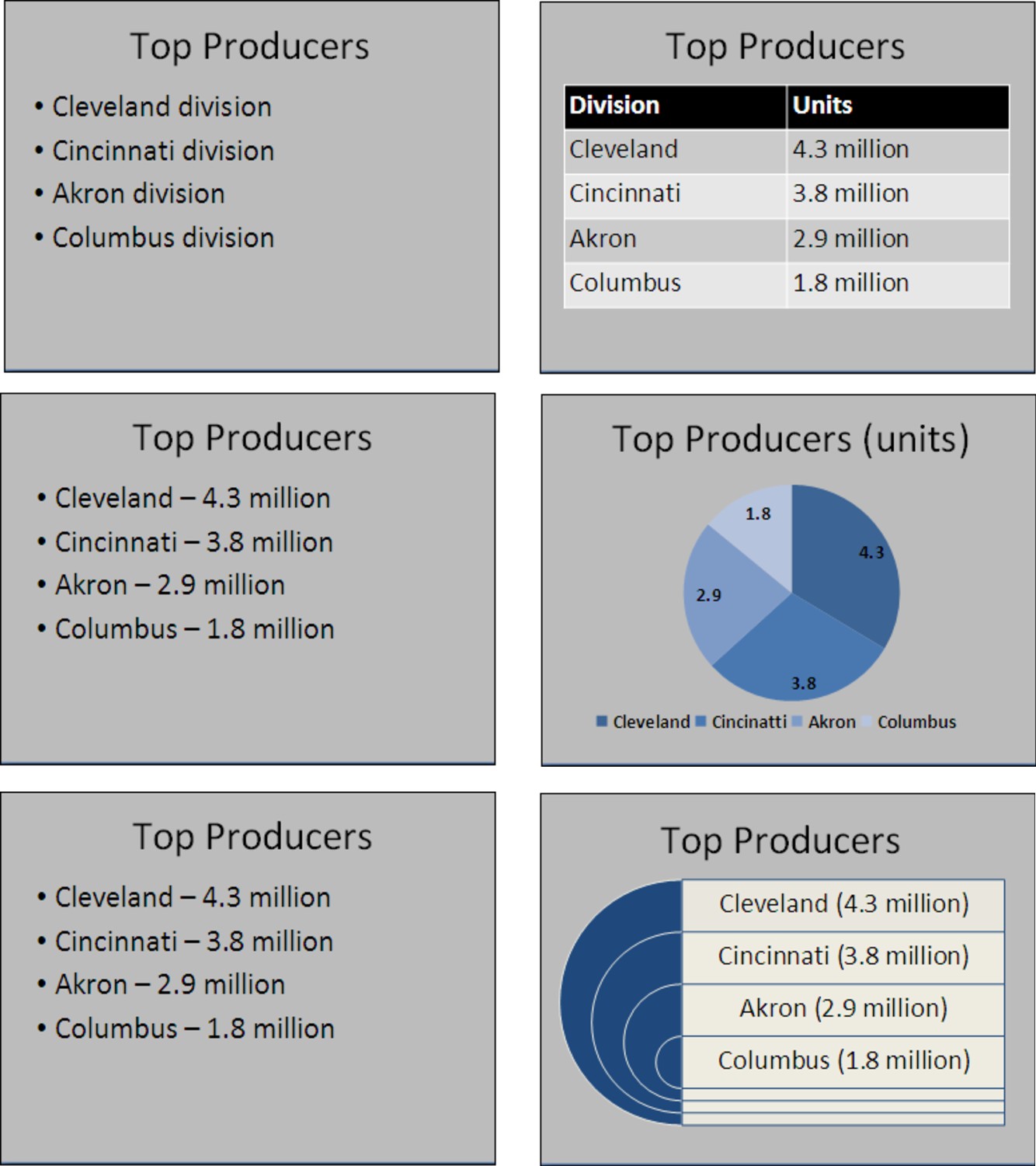

Many PowerPoint slide layouts are made for bulleted lists, and many people are tempted to make these lists, but before you consider making one, ask yourself whether the information you want to present in the list could be better presented in a table, chart, or diagram. Figure 4-1 demonstrates how a bulleted list can be made into a table, chart, or diagram. Consider tables, charts, and diagrams before you reach into your ammunition bag for another bullet:

Table: In a list that presents raw data, consider using a table. In a table, your audience can see numbers as well as names. The numbers can help to make your case.

Table: In a list that presents raw data, consider using a table. In a table, your audience can see numbers as well as names. The numbers can help to make your case.

Chart: In a list that compares data, consider using a chart. The audience can see by the bars, columns, or pie slices how the numbers compare.

Chart: In a list that compares data, consider using a chart. The audience can see by the bars, columns, or pie slices how the numbers compare.

Diagram: In a list that presents the relationship between people or things, use a diagram to illustrate precisely what the relationship is.

Diagram: In a list that presents the relationship between people or things, use a diagram to illustrate precisely what the relationship is.

Observe the one-slide-per-minute rule

At the very minimum, a slide should stay on-screen for at least one minute. If you have been given 15 minutes to speak, you are allotted no more than 15 slides for your presentation, according to the rule.

Rules, of course, are made to be broken, and you may break the rule if your presentation consists of vacation slides that can be shown in a hurry. The purpose of the one-slide-per-minute rule is to keep you from reading from your notes while displaying PowerPoint slides. Remember: The object of a PowerPoint presentation is to communicate with the audience. By observing the one-slide-per-minute rule, you make sure that the focus is on you and what you’re communicating, not on PowerPoint slides.

|

Figure 4-1: List information presented in a table (top), chart (middle), and diagram (bottom). |

|

Make like a newspaper

As you write slide titles, take your cue from the editors who write newspaper headlines. A newspaper headline is supposed to serve two purposes. It tells readers what the story is about but it also tries to attract readers’ attention or pique their interest. The title “Faster response times” is descriptive, but not captivating. An alternative slide title could be “Are we there yet?” or “Hurry up and wait.” These titles aren’t as descriptive as the first, but they are more captivating, and they hint at the slide’s subject. Your talk while the slide is on-screen will suffice to flesh out the topic in detail.

Put a newspaper-style headline at the top of each slide, and while you’re at it, think of each slide as a short newspaper article. Each slide should address a specific aspect of your subject, and it should do so in a compelling way. How long does it take to read a newspaper article? It depends on how long the article is, of course, but a PowerPoint slide should stay on-screen for roughly the time it takes to explore a single topic the way a newspaper article does.

Use visuals, not only words, to make your point

Sorry for harping on this point, but you really owe it to your audience to take advantage of the table, chart, diagram, and picture capabilities of PowerPoint. People understand more from words and pictures than they do from words alone. It’s up to you as the speaker, not the slides, to describe topics in detail with words.

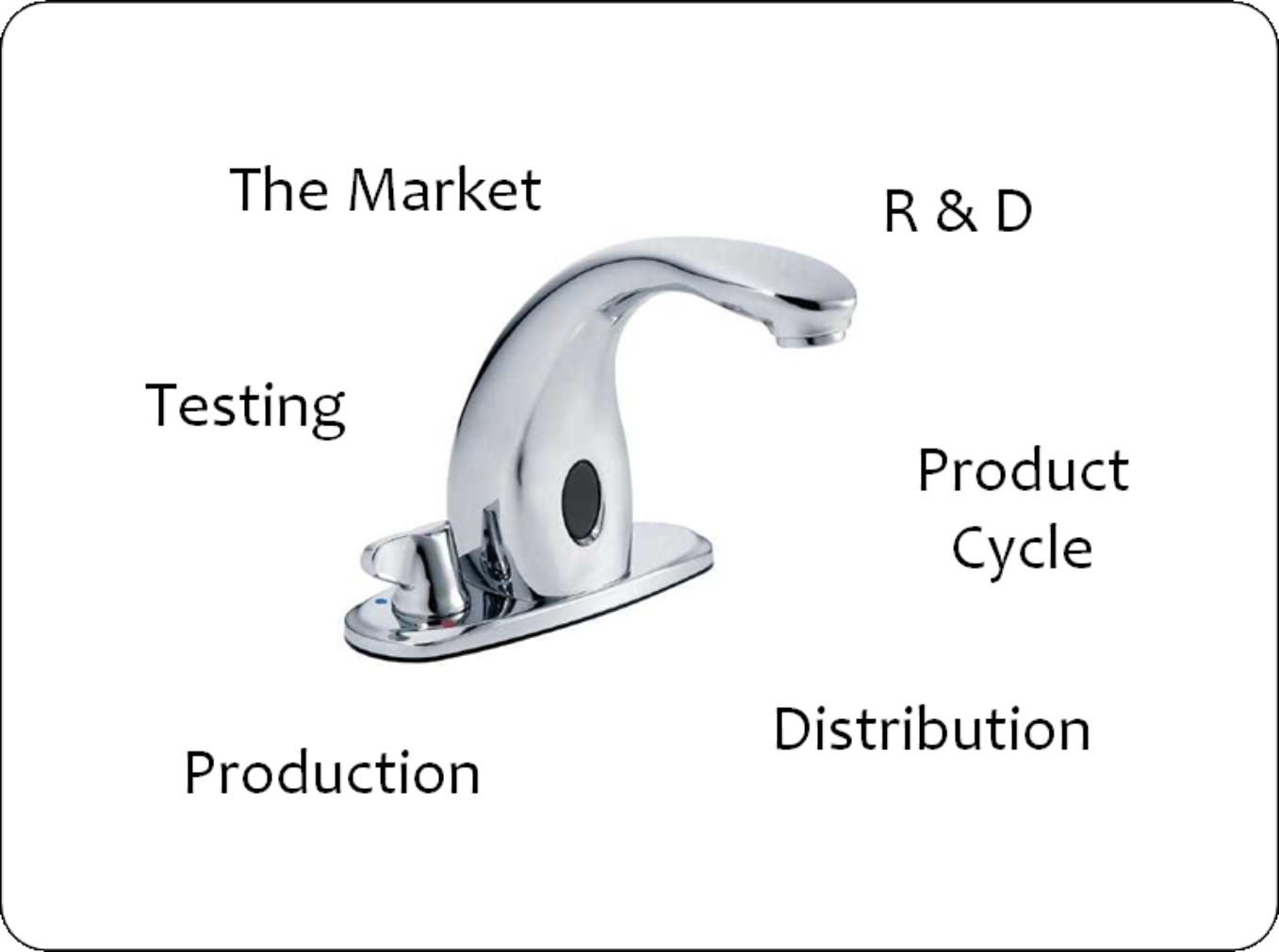

Figure 4-2 shows an example of how a few words and a picture can convey a lot. This slide comes from the beginning of a presentation. It tells the audience which topics will be covered. Instead of being covered through long descriptions, each topic is encapsulated in a word or two, and the graphic in the middle shows plainly what the presentation is about. The slide in Figure 4-2 was constructed from text boxes and a graphic.

|

Figure 4-2: Combining words and a picture in a slide. |

|

Delivering Your Presentation

As one who is terrified of speaking in public, I know that most advice about public speaking is gratuitous advice. It’s easy to say, “Don’t be nervous in front of the audience,” or “Direct your nervous energy into the presentation,” because not being nervous is easier said than done. Following are some tips — I hope they aren’t too gratuitous — to help you deliver your presentation and overcome nervousness.

Rehearse, and rehearse some more

The better you know your material, the less nervous you will be. To keep from getting nervous, rehearse your presentation until you know it backward and forward. Rehearse it out loud. Rehearse it while imagining yourself in the presence of an audience. PowerPoint offers a Rehearse Timings command for timing a presentation, seeing how long each slide remains on-screen, and seeing how long a presentation runs (see Book V, Chapter 1). Take advantage of this command as you rehearse to find out whether your presentation fits the time frame you have been allotted for giving your presentation.

Connect with the audience

Address your audience and not the PowerPoint screen. Look at the audience, not the slides. Pause to look at your notes, but don’t read notes word for word. You should know your presentation well enough in advance that you don’t have to consult the notes often.

I have heard two different theories about making eye contact with an audience. One says to look over the heads of the audience and address your speech to an imaginary tall person in the back row. Another says to pick out three or four people in different parts of the room and address your words to them at various times as you speak. The main thing to remember is to keep your head up and look into the audience as you present your slides.

Anticipate questions from the audience

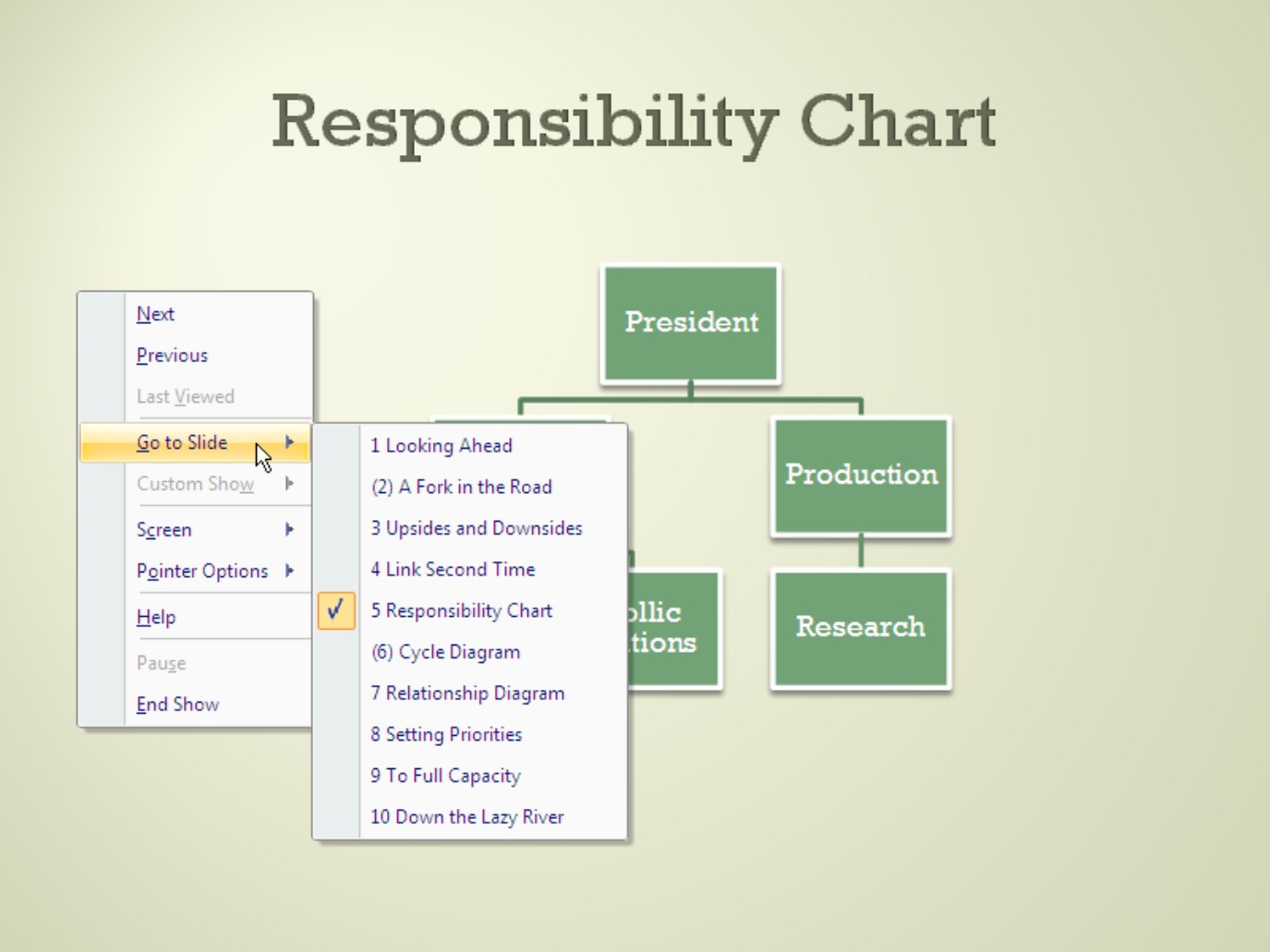

If you intend to field questions during a presentation, make a list of what those questions might be, and formulate your answers beforehand. You can “hide slides” in anticipation of questions you will be asked. As Book II, Chapter 1 explains, you can create hidden slides and show them if need be during a presentation. Book VI, Chapter 1 explains how to create a customized presentation — a secondary presentation consisting of a handful of slides — and show it during a presentation if the occasion arises. Figure 4-3 shows how to select a hidden slide during a presentation.

|

Figure 4-3: Showing an optional hidden slide in the middle of a presentation. |

|

Know your equipment

These days, conferences where PowerPoint presentations are shown accommodate PowerPoint presenters. If you have a laptop, all you have to do is plug your computer into the presentation system. Chances are, someone will be there to help you set up your presentation.

.jpg)

Take control from the start

Spend the first minute introducing yourself to the audience without running PowerPoint (or, if you do run PowerPoint, put a simple slide with your company name or logo on-screen). Make eye contact with the audience. This way, you establish your credibility. You give the audience a chance to get to know you.

Play tricks with the PowerPoint screen

In the course of a presentation, you can draw on the slides. You can highlight parts of slides. You can also make the screen go blank when you come to the crux of your presentation and you want the audience’s undivided attention. In all my years of watching PowerPoint presentations, I have seen few people take advantage of these little screen tricks, but I think they make for much livelier presentations. Book VI, Chapter 1 explains how to draw on slides and blank the screen.