— 1 —

Anybody

Friday, January 14, 2005

O’Grady’s Roadhouse

Upper James Street, Hamilton, Ontario

Friday night, good friends, hot wings, cold draught, and their song playing — Brenda and Art’s. Brenda swayed under the lights on the tiny dance floor in her slim jeans, heels, scoop-necked white shirt. They used to sing karaoke to it together years ago while enjoying a few beers.

It was Janis Joplin singing “Me and Bobby McGee,” a song about a couple hitching south, nothing in their future but a song and an unknown destination. Joplin’s leathery voice, and the folksy 1960s rhythms carrying Brenda away once again.

But feeling good was easy Lord, when he sang the blues

Hey, feeling good was good enough for me

Good enough for me and my Bobby McGee

Art? Her husband was close by, yet too far away. Off the dance floor, through the dingy lighting of the bar, back, behind a closed door, in a cramped hallway outside the bathroom. It could be anybody back there, beaten to the floor. But it was not. It was Art.

O’Grady’s roadhouse, where Art Rozendal was beaten to death.

John Rennison, Hamilton Spectator.

Another blow. Another. Art was defenceless; his only shield the mercy of his attackers — of which there was none. Blood was pooling in his eye sockets.

At the front of the bar, a customer rose from his table. He’d just got off work and needed to wash his hands. He walked to the back, opened the door to the hallway, and saw the man face down on the floor. His hand still gripping the doorknob, he stared at them, saw anger, cruelty, almost an evil light in the faces looming over the body.

“Do you want some of this?” one of them threatened.

A metallic flash. There was something in his mouth, like wire, almost like fangs. And now, the man’s open hand pressed in the customer’s face, against the jaw bone, casually shoving his head against the wall as he passed by.

They got away, all of them, past the bar, dance floor, out the front door, emerging from the heat into the cold on Upper James Street.

Beep. Beep. Beep.

Maloney rolled over and smacked the alarm on his night table. Morning? He rolled out of bed, staggered to the washroom in the dark, then returned to the bedroom.

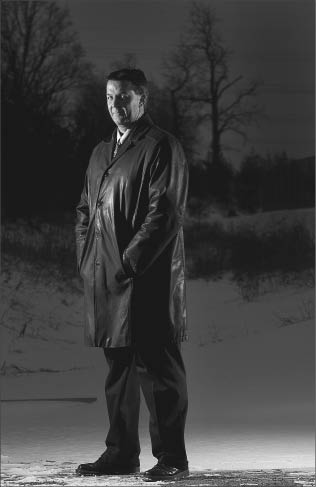

Lead homicide detective Mike Maloney.

John Rennison, Hamilton Spectator.

Beep. Beep. Beep.

“Would you turn your pager off?” his wife murmured.

He stared at the night table. The pager. Now his eyes focused on the clock. He had only been asleep an hour or so. Was it just him, or did they always wait to call until after he had settled into a deep sleep? Homicide Detective Mike Maloney grabbed the pager, padded downstairs in his boxers to the living room, fumbled for the light switch, grabbed a piece of paper, and picked up the phone. Who am I calling anyway? he wondered. Had to be Peter. Maloney dialed. Detective-Sergeant Peter Abi-Rashed, senior man in the major crime unit of Hamilton Police, answered.

“Hello, this is Mike,” Maloney said.

“What are you doing?” Abi-Rashed asked.

“What do you mean what am I doing?”

“We got one,” Abi-Rashed muttered in the fatigued tone Maloney knew all too well. “You want to pay off your mortgage early?”

“It’s already paid.”

“You coming in?”

“I’m up now.”

Maloney marched back upstairs, showered and shaved. He was 45, had 27 years under his belt as a cop in Hamilton, the past few years in homicide branch, and as he looked in the mirror at the blue eyes and face that stared back at him, he could see the wear of those years. But he wasn’t an old man yet; there was still a boyishness, too.

He plugged in the iron. Domestic chores were not Maloney’s strong suit. Ironing was an exception. During the week he always ironed the next day’s dress shirt the night before. But this was supposed to be a weekend off. He slipped on the pressed shirt and the rest of his suit — the uniform homicide detectives were expected to wear when on the clock. Technically, he didn’t have to report, but Maloney was well versed in the culture among his fellow detectives downtown. You get the call, you report.

He enjoyed the work, but was starting to think about hanging it up, leaving homicide. Sexual deviants, brain dead killers, bloody crime scenes, and, worst of all, connecting with families of murder victims — there was no closure for them, ever. Maloney could not remember once leaving court and truly feeling pleased with the result. It took a toll. He loved working with the detectives — best group he had been with in his years on the force — but enough was enough.

This new case was about to test Maloney’s view of his job even more. Every murder matters; it’s always tragic when someone takes life from another. But the reality, known all too well by those working homicide in Hamilton, was that many victims were people who routinely danced with the devil, who embraced high-risk lifestyles, or became trapped and got burned. But the victim in this new case was not one of those people. Not even close. Could have been anybody. That was what really turned the stomach; that’s what would make this one linger with Mike Maloney more than most.

Maloney got in his car and started his drive to Central Station from his home in Ancaster. He drove down the Mountain, savouring the calm, Hamilton lying below enveloped in black. The thought occurred to Maloney at times like this: it was a nice looking city — and yet, down there something very bad had happened to somebody. The next 15 hours were going to be hell.

“Assault, 5-9-2 Upper James Street.” The uniformed officer heard the call in his cruiser. A fight at a bar on a Friday night in Hamilton? Constable Ian Gouthro was hardly surprised. He had reported to his share of them. He was on patrol less than five minutes from the scene, which was a strip mall pub named O’Grady’s Roadhouse. He radioed dispatch and said he would head over. Gouthro parked, walked to the front door. He expected to find a man inside with a bloody nose, the result of a routine liquor-induced scrap. By the time he marched inside O’Grady’s, the latest information from dispatch indicated the suspects in the assault had fled. But entering a crowded and well-oiled bar after a fight was never a predictable situation.

“I’ve arrived,” he said into his radio. “Entering.”

“Do something! You gotta do something! He’s in the back!”

Chaos, yelling, screaming. Gouthro’s eyes adjusted to what seemed like an unusually dark bar. “Show me where he’s at,” he said, staring ahead.

All around were indistinguishable voices. He ignored them, ignored the milling throng; he had tunnel vision focused on the back of the building. Someone held open a door revealing the hallway by the bathroom. He noted a man on his back on the floor, blood on his nose and mouth, and a female on her knees beside him in hysterics.

“Do something, please! It’s my husband. He’s not breathing.”

“Speed up the ambulance,” he said into his radio.

Gouthro’s heart pounded, but he kept his expression flat. He needed the woman’s help until the paramedics arrived. He had a forceful but soft-spoken way about him.

“Look into my eyes,” he said. “We’re going to do this; we’re going to get through this. Okay?”

She listened, nodded, did what she was told. She told the officer her name: Brenda Rozendal. Her husband’s name was Art. Both were 44 years old. They had been married 20 years. Had two boys.

At that moment, in the white space between life and death, could Art sense anything? Did his mind’s eye take him back through the past? The boy at home outside Hamilton, God’s country, an infinite quilt of farmers’ fields under a big sky; the young man with a thick moustache and broad smile hanging with his friend Bill in a garage, oil-stained hand clutching a silver wrench, lovingly bringing a classic car back to life — FM rock on the radio, and a cold OV waiting in the fridge; the grown man looking into Brenda’s eyes at the kitchen table, the diamond sliding on to her finger, her nails shiny from a fresh coat of red polish.

The police officer and Brenda performed CPR. Brenda blew air into his lungs. There was no response. She could taste Art’s blood on her tongue.