— 13 —

Winding Roads

Cory McLeod fears his dreams, and so stays up late each night in his cell, till 2:30, 3:00 a.m. — it allows him to drift into the kind of unconscious sleep where images of his past do not visit. It’s the things he has seen — the graphic photos of Art Rozendal the police showed him among them. When he does dream, sometimes it is of that night at O’Grady’s. Except sometimes it plays out differently; he and Kyro don’t beat up Art. Or Art even beats on them. Or nothing happens between them at all.

In Millhaven, a maximum security prison near Kingston, Ontario, Cory has a prayer mat in his cell, says he has found religion, is a practising Muslim. He speaks quickly, is animated. He expresses remorse for what happened; believes he and Kyro deserve every punishment they got, if not more. He lives in J-unit, where Canada’s hardest criminals are kept. The way Cory sees it, he can use his time in jail to change who he is. In a way, he thinks, somebody lost their life so he can better his, even if that “might seem a fucked-up way to look at it.” He feels he owes it to the Rozendals to turn his life around.

Does Cory mean what he says? Is he just playing another game? If so, to what end? He sees Kyro in jail regularly; they are on the same security range. They are still close friends. Workout at the same time with weights. Not together, though. They can’t agree on the routines. Cory still loves Sherri Foreman, was shocked she did that for him, stonewalled the police. He is proud, in a way, but also wishes she hadn’t done it. If she had co-operated with police, they could still be in touch today. As it is, Sherri is legally prohibited from any contact with him.

In February 2007 Sherri Foreman and Katrina McLennan pleaded guilty and were convicted for obstructing police. The judge said the girls had been “attracted to the gang lifestyle.” Their conduct “struck at the heart of the administration of justice,” and “showed a lack of respect for human life and a lack of respect for the people of Hamilton.” Due to the timing of their bail hearings, Sherri ended up spending 50 days in jail, Katrina 23. The judge sentenced them to time served and three years’ probation. They must stay out of Hamilton and have no contact with Sparks or McLeod.

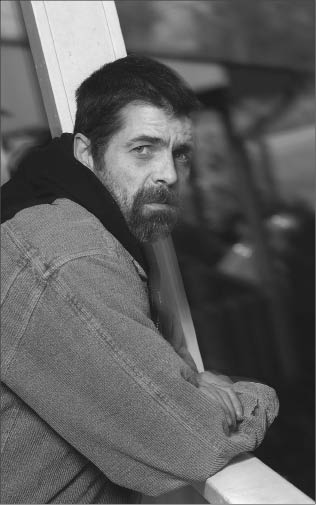

Kyro Sparks? He wears a white Nike hat perched sideways on his head, the price tag still attached. Unlike Cory he speaks guardedly, measuring his words. Won’t talk about the homicide, or his version of what happened in the bathroom.

“I’d like to talk about it,” he offers, “but not until I talk to my co-accused.”

Why did he beat up Art?

“I’ll decline to answer that question.”

Does he wish Art had not died that night?

“I don’t wish death on nobody, not even my worst enemies.”

Does he feel the Rozendal family’s pain, having lost a father and husband?

“Do I feel their pain?” he repeats, a puzzled look on his face.

He looks away in thought for several seconds. Before he can form an answer, a guard comes and takes him back to his cell, the thick black steel door automatically clanking into place behind him.

Art’s old friend from work, Charlie Montgomery, drove up the Mountain to visit Brenda. He had some things to give her. In the coke ovens at Stelco, Art’s locker had remained untouched long after he died; inside were his tools, his clothes — and the tarnished helmet that hung from a hook on the wall. None of the guys could bring themselves to touch any of it, least of all Art’s supervisor, Ken, a guy who wore his heart on his sleeve. Finally, Charlie decided that it was time. So on an August day, two and a half years after Art was killed, when Charlie pulled up Brenda’s street, Art’s clothes were in the back of his car. He had carefully set the helmet on the front passenger seat. Felt good to hand the helmet over. Art’s boys should have it.

Art’s oldest son, Neil, talks openly about his father’s death and the effect it has had on him and his family. It helps him to deal with his loss. He talks, to a journalist, family, about his dad, the pain. That’s his way. Jordan, who is quieter, keeps to himself, says little. He inherited Art’s mechanical abilities. Eventually, Jordan found his way into Art’s garage, the one that still has the girlie tool calendars, a collection of dented licence plates — and a ’68 buttercup-yellow Buick GS 400. Art had taken it apart, the engine sits on the floor. Never did finish it. Jordan took over the project.

The day Charlie Montgomery came out, Brenda held a backyard barbecue for a few friends and family. A good time, but then it seemed to collectively hit everyone at once. Brenda had bought these great steaks. But who would cook? Anyone can grill a steak, but nobody did it like Art. He had his special marinade, and the way he seared them locked in the flavour. Everyone just stood there, staring at the empty barbecue, and that’s when it occurred to Charlie. The family is still living with Art. Except he’s not here.

On the third anniversary of Art’s death, Brenda awoke early with tears in her eyes. The morning broke grey, shrouded in fog. She drove with Neil and Jordan to Woodland Cemetery. They gathered at Art’s plot and held hands. Bev had put a little angel figure there. Inset in the stone is a picture of a red ’71 Buick Skylark, the first one Art got Brenda. On the stone Brenda had a quote inscribed: “The love we shared will never die.”

Like every time she visits, she laid three single roses. The yellow rose symbolizes friendship, the white symbolizes purity, and the red, love. Then Art’s wife and two sons left, drove over a wooden bridge crossing an inlet of the lake that bends into the property, where Art and Brenda had once posed for their wedding photos.

Brenda visited the cemetery every day for about a year after he died. Then it was probably once a month, when she had the day off from her work in home health care. She keeps busy with the boys, work, friends, family, and volunteering with Hamilton Police Victim Services, where she helps counsel loved ones of homicide victims. She misses Art every day, but also fears forgetting too much, worrying that with time he will fade. What did he sound like? What did he smell like?

She worries that the strongest memory lodged in her mind’s eye is not the smile and laughter, but Art dying in O’Grady’s. She swears she can still taste his blood on her tongue, and no amount of cigarettes can make it go away.

On that anniversary of his death, the fog cleared, the wind picked up; the air was bitterly cold. She drove with the boys up Upper James Street to the bar. It’s not called O’Grady’s Roadhouse anymore. Neil wanted to go. He drops in the bar once a year by himself; Brenda doesn’t like him doing it. Today, she didn’t want to go, but went to be with him. Jordan remained in the van with a friend of his. It was quiet inside the bar: two, maybe three people, middle of the afternoon, sports on TV. Brenda and Neil sat near where their old table had been. A waitress came over. “Can I get you a drink?” They ordered two Canadians.

“To Art,” she said, her voice shaking. Neil stared at the spot at the bar where he had last seen his dad alive. Then he stood and walked to the back hallway. There was no longer a door concealing the back; you could see right through to the bathroom area. Brenda looked over her shoulder at Neil. Her hands shook, just a bit, and her eyes looked glassy.

She had done this once before, last year; came to the bar to confront the demons. And here she was doing it again, as though forcing herself to feel pain, because even the pain of remembering how he left her was better than not feeling him at all. Neil punched in music on the juke box. One of Art’s favourites: “Wonderwall” by Oasis.

And all the roads we have to walk along are winding

And all the lights that lead us there are blinding

Before Brenda and Neil were ready to leave, Jordan entered through the front door. The family was in the place all of 20 minutes. Brenda and the boys walked to the back hallway, stood, bowed their heads for a moment. Then the three of them turned and walked out the front door.

Art’s younger brother Darren moved back to Hamilton and got a place in the north end; found work dealing with heating and cooling systems,

Art’s brother, Darren, struggled to cope with his anger.

John Rennison, Hamilton Spectator.

duct work. He is around Brenda’s place nearly every day, helping out with the boys, fixing stuff.

He is not coping. It’s not just the grief, which is constant. He thinks of Art every day. When Art died Darren lost a brother and father figure on the same day. He just misses having him around. More than grief, though, he feels anger. It will not leave. The thing is, he knows Art would actually have had it in his heart to forgive the ones who killed him. He really would. Art was just like his mom, had strong faith. Darren? Forgive? No. Truth is, he’d like an hour in a room alone with each of those guys. Eye for an eye. It’s in the Bible. He knows Art would tell him, “Darren, you have to forgive. Have to move on. Don’t think about the past.” But see, Art’s not here to say it. Because they took him away.

Some of Art’s gifts, though, nobody can take away. Darren has seen Art in a dream — just once. In the dream Darren is sleeping and is awakened by the sound of a voice. He peers across the darkened room, and there is Art, sitting up in his own bed, looking at him. The voice is quiet. “Come here,” Art says. Darren rises, shuffles over and kneels. Art leans in and hugs his brother, holds him tight. The grip loosens and Darren gently lays Art back down again.

Brenda Rozendal recently sold the house she had shared with Art and her sons. She has done volunteer work with Hamilton Police Victim Services, helping others who face traumatic loss.

Mike Maloney retired after 32 years and eight months with a badge. He says he never thinks about Sparks and McLeod, but still thinks about the Rozendals and other families coping with incomplete justice, and is still in touch with some of them, including Brenda. He golfs a few times a week with a couple of retired cops. His shots don’t always fly straight but they fly straight enough, and the beer after the round is always cold: “It’s just nice to be out there. Being a police officer taught me that life is fragile and fleeting — enjoy while you can.”

Kyro Sparks and Cory McLeod became eligible for early release in the fall of 2012. January 2013 will be the eighth anniversary of Art’s death. Art would have turned 52 in February 2013.