Conclusion: Let’s Make a Dream

128. ‘Universal folly’, noetic dreams and τέχνη

Well after the ‘great confinement’ of 1656, the Marquise de Sablé writes in her Maximes that ‘the greatest wisdom of man consists in knowing his madness’.1 The exclusion of madness, consigning it to the exterior of reason, was obviously not something accomplished at a single stroke. In ‘Sagesse et folie dans l’oeuvre des moralistes’ (published in 1978 but containing no reference to Foucault’s History of Madness), Margot Kruse shows that, under the influence of Baltasar Gracián’s The Art of Worldly Wisdom,2 the moralists of the eighteenth century – in particular François de La Rochefoucauld, Nicolas de Chamfort and Madeleine de Sablé – put the question of a ‘universal folly’ at the heart of their studies of morality and character: ‘Even more often than the idea of the perpetually reversible relation between wisdom and madness [that we find in Montaigne a century earlier], we find in the moralists of the seventeenth century the idea of “universal folly”.’3 This research shows that in the ‘classical age’, a long process of diluting madness into reason unfolds over more than two centuries.4 Nine years after the founding of Paris’ Hôpital général, La Rochefoucauld writes that the ‘most refined folly is begotten by the most refined wisdom’.5 This in no way invalidates Foucault’s thesis according to which 1656 is the year of the institutional turn that inaugurated the ‘great confinement’ and established a new relationship to madness fifteen years after the Meditations of Descartes – heralding a new ‘epoch’ of madness. On the contrary, it confirms that madness, the definitions of which evolve over time, perpetually haunts the discourses derived from noesis as that with which the latter must constantly compose – whether positively or negatively, intermittently and in many ways, which may specify epochs and, perhaps, specify eras.

We ourselves, latecomers of the twenty-first century, fashion for ourselves, and in the absence of epoch, a new experience of madness – ordinary, extraordinary, reflective, and threatening to turn into a generalized madness, that is, into a panic of unimaginable magnitude. We suffer this ordeal while disruption continues to radicalize the paradoxes of the Anthropocene, which got underway at the end of the classical age as a sudden intensification of disinhibition. Disruption: or what, in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Jonathan Crary has described as the prevention of dreaming.6

In this context, we must rethink the status not just of madness, but of the dream qua origin of noesis. This is a task of the utmost urgency, because we know, today, how the prevention of dreaming can drive us crazy, to the point of becoming criminal, and because only a new noetic dream can yet save us.

If in reading Descartes, and in general, it is necessary to distinguish dream and madness, as Foucault asserts, the articulation between them must also be undertaken with respect to the pharmakon, that is, tertiary retention: it is the noetic dream that engenders the pharmakon, which, like τέχνη, can drive us crazy. The noetic dream is the condition of exosomatization, which always brings with it the possibility of ὕβρις.

When the ὕβρις provoked by the toxic becoming of the pharmakon makes us go crazy, we need a dream with which to cure this madness – which always inclines towards despair, which always turns to despair, from which it can find its energy. Such a dream – careful, therapeutic – which bears a resemblance to the creative madness referred to by Erasmus when he reads Saint Paul,7 is noetic in the sense that it produces hope, and, along with hope, courage. In summary:

- What we call madness is what the ancient Greeks always related back to ὕβρις.

- This ὕβρις is the fact of exosomatization, which the Greeks called τέχνη (tekhnē).

- After the tragic origin of Western thought, what we call moral philosophy stems from αἰδώς and δίκη, the ordeal of which is embodied by Pandora and her fetishes – and the disavowal of which begins with Plato, who thereby inaugurates metaphysics.

- The experience of ὕβρις arises again today in the ordeal of disruption, as the excessiveness of the absence of epoch, as the becoming without future that provokes a mad panic – strangely echoing the Renaissance as examined by Foucault at the beginning of History of Madness.

- The character of the current forms of madness finds its point of departure in the disavowal of the madness in reason, and hence in the disavowal of modern ὕβρις, in and by modern metaphysics.

- Despite all its efforts to shake up this disavowal, twentieth-century philosophy, especially in France, itself remained caught up in this very same disavowal, as did psychoanalysis – thereby feeding into a kind of ‘postmodern’ metaphysics.

- Heidegger, insofar as he thinks what we are here calling archi-protention, in addition to thinking Gestell and Ereignis, remains an indispensable interlocutor. But he himself is in denial. This is reflected in: (1) the opposition he makes between calculative thinking and meditative thinking; and (2) his neglect of the archi-protention of life that we might call being-for-life, or again, being-for-noetic-life.

129. The folly of the cross, and the dream according to Foucault in 1954

In the pharmacological and organological situation that results from exosomatization, and as the ‘wisdom’ that ‘knows its madness’, reason, which designates noesis insofar as it exceeds all calculation – but insofar, too, as it passes through calculation, with which it distributes the hypomnesic tertiary retentions that spatialize the time of its dreams, which thereby become noetic (which Heidegger wants neither to see nor hear, the roots of his anti-Semitism lying in this very fact) – in this situation, then, reason, inasmuch as it is not simply ratio, can only ever be intermittent.

In his praise of stultitia (a word that means both madness and stupidity – in the sense of the state of stupor), Erasmus, himself referring to Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians and the ‘folly of the cross’,8 distinguishes between

‘two kinds of dementedness’: a calamitous and devastating madness, opposed to a creative and positive madness. […] At the end of The Praise of Folly, positive and Christian stultitia, in Saint Paul’s sense, is linked to the ancient conception of madness in a positive sense that, according to Plato, distinguishes lovers, prophets and poets. Seneca goes further when he asserts, referring to Aristotle: […]‘No genius has ever existed without a grain of madness.’9

Madness is that through which we may pass, including as the madness of calculation, but it is where we must not remain, so that it may become the remarkable, improbable and neganthropic moment of a noetic intermittence that could never last forever: that will never be anything more than a différance. A kind of dream [rêve]. A reverie [songe].

It is in this way that madness, which is not dreaming, is nevertheless connected to the dream, which, insofar as it is noetic, is itself connected to exteriorization, and in a way tied to exteriorization, that is, to exosomatization. In exosomatization, the dream is linked to tertiary retention, both upstream and downstream. The so-called ‘higher’ animals, who also dream, and do so because they sleep, nevertheless do not realize their dreams: they do not exosomatize them, they do not express them.

Here it is necessary to go back to the young Foucault and to his dream of 1954, where, reading and interpreting Binswanger, as I have already said,10 he envisages an anthropology that would above all be an oneirology, itself consisting in an interpretation of Being and Time on the basis of the clinical psychiatry that lies at the origin of Daseinsanalyse. At the beginning of his introduction to ‘Dream and Existence’, Foucault declares:

In another work we shall try to situate existential analysis within the development of contemporary reflection on man, and try to show, by observing the inflection of phenomenology toward anthropology, what foundations have been proposed for concrete reflection on man.11

What should we expect from such a work with respect to the dream?

The introduction to ‘Dream and Existence’ undoubtedly shows us the key idea. After stressing that with Freud, who re-evaluates the nocturnal ‘oneiric experience’ that the modern age had reduced to the ‘non-sense of consciousness’, the dream is already on the way to becoming a kind of realization, Foucault argues that Binswanger makes it possible to think the dream as that which constitutes ‘the point of origin from which freedom makes itself world’:

By breaking with the objectivity which fascinates waking consciousness and by reinstating the human subject in its radical freedom, the dream discloses paradoxically the movement of freedom toward the world, the point of origin from which freedom makes itself world. The cosmogony of the dream is the origination itself of existence. This movement of solitude and originative responsibility is no doubt what Heraclitus meant by his famous phrase, ‘idios kosmos’.12

Hence the ἴδιος κόσμος lies at the very heart of Binswanger’s reflections.13

It is a question of going beyond the Freudian function of the dream and its interpretation.14 Contrary to what this Freudian interpretation suggests (according to Foucault), what is at stake in the dream and in what the dream expresses ‘is not the biological equipment of the libidinal instincts; it is the originary movement of freedom, the birth of the world in the very movement of existence’.15

Beyond the Foucauldian hypothesis (I note in passing and not without astonishment that Foucault, too, confuses instinct and drive), but in its logical extension, and as what seems to me to be confirmed by the facts, we must now posit that:

- this movement fundamentally belongs to the process of exosomatization, which enables and is enabled by the noetic dream as the power to bifurcate neganthropologically – for example, with the onset of expression via parietal art, between the Aurignacian and the Magdalenian;

- the ‘inflection of phenomenology toward anthropology’16 emphasized by Foucault in 1954, which for him, as for Binswanger, clearly passes through Heidegger’s existential analytic, must be pursued beyond anthropology and beyond the existential analytic, against the entropology that anthropology has become (as Lévi-Strauss himself put it in 1955), and for the Neganthropocene.

This is why, as in Miyazaki – interpreter of Valéry, and, through Valéry, interpreter of Pindar – the ‘dream is not a modality of the imagination, the dream is the first condition of its possibility’.17 But here we must add, with Pindar, Valéry, Miyazaki and Simondon,18 that the first condition of this first condition of possibility of the imagination that is the dream is the image-object, that is, μηχανῆ (mekhanē), which is to say, τέχνη.

Which is to say, ὕβρις.

130. The madness of capitalism

If madness is what is unleashed by ὕβρις, purely and simply computational capitalism is the madness of our age in the absence of epoch. This age of absolutely computational capitalism is without epoch because an epoch is always what, as ἐποχή, suspends the time of mere calculation, but does so by passing through it, going with it, leaping beyond it, over and above it, and, as I have argued in Automatic Society, Volume 1, ‘above and beyond the market’.19 That such a leap, which Heidegger does indeed discuss,20 passes through calculation, that it presupposes calculation – this is precisely what Heidegger cannot manage to think.21

Calculation is the fate of the understanding that, passing through its exteriorization as prescribed by Descartes’ fifteenth and sixteenth rules for the direction of the mind, is bound to find itself exteriorized. The question of reason then arises in other terms, which can only be those of a pharmacology – in which there is not, on one side, authentic thinking, that is, meditative thinking, and, on the other side, calculative thinking, that is, ‘uprooted’ thinking.22

Heidegger does not see that what he calls Eigentlichkeit (translated as ‘authenticity’, ‘propriety’, ‘ownmost-being’) stems, not from a native land, but from an idiocy that provides the idiomaticities that express an originary default of native language, as well as of the original and the origin, of whatever kind. He does not see this because this idiocy always carries within it a locality that is a given place in which time is given only as its spatialization, which is also and ‘always already’ its deterritorialization – its exosomatization.

The default of language (the shibboleth23) of which this idiomaticity is the consequence, always lived and perceived as the other’s default of pronunciation, stems from the argument advanced by Derrida against Being and Time under the names of archi-trace and archi-writing.24 But Derrida himself did not follow his own meditation on différance all the way out – nor did he do so for his own meditation on calculation, which showed, precisely, that différance must always pass through calculation.

All of Heidegger’s political shifts, ambiguities and cowardice derive from the disavowal of the default of origin that prevents thinking locality as what takes place through the arrangement of space and time via tertiary retention – an arrangement of space, time and retention by which and in which bifurcations are produced. Through such a bifurcation, a difference is inscribed against indifferent becoming, thereby making (a) différance, but this also, and as pharmakon, erases this difference – like Hermes stealing cattle from his half-brother Apollo.

What remains to be produced on the basis of the Derridian deconstruction of the Heideggerian Abbau is an organology that enables a positive pharmacology of the present ‘monstrosity’ that is our situation in the absence of epoch. Such a positive pharmacology passes through a ‘history of the supplement’ that must be actualized and conceived as exosomatization.

Over the history of the noetic supplement, and since the Renaissance, madness has unfolded in relation to a process of disinhibition that leads to the disintegration of the moral being. This disintegrating disinhibition is possible only because the moral being is originally bipolarized by a field of transindividuation that is metastable only because it is hybrid, that is, ceaselessly composing with the ὕβρις that it contains, and that always returns to haunt it, dephasing it.

It is from this hybrid ground that disadjustments and readjustments are possible, oscillating within what Simondon describes as bipolar metastability. Bipolarity is not merely psychic: it forms between collective individuations and psychic individuals insofar as they are traversed by an indefinite dyad passing through the collective. It is in this very way that this being is moral, that is, social. The dyad that traverses the moral [le moral] insofar as it is indissociably psychic and social is a constant test of temptations that are not simply opposed, but composed.

By opposing Good and Evil, monotheism will decompose these compositions. In so doing, it ends up unbinding and unleashing the drives – in becoming the ‘spirit of capitalism’, and ultimately by doing the precise opposite of the prescription it had offered through the life of Jesus. Transformed into capitalism, and as a process of disinhibition, monotheism now threatens to end in a war of all against all, of everyone against everyone, including against themselves, through an immense discord generated by this madness that is despair (like the ‘calamitous and devastating’ dementedness of which Erasmus speaks).

Nothing is more threatening than the mortiferous energy of despair that we see accumulating everywhere – and not just among those young people deprived of idealization whom the ‘jihadist offer’ tries to seduce. This mortiferous energy, the energy of desperation, can be ‘rectified’ [redressée] (just as one rectifies an alternating current into a direct current – by differentiating polarities) only through the quasi-causal transformation of this hyper-entropy into an unprecedented neganthropic possibility. So-called ‘de-radicalization’ is in this regard bound to be inconsequential if it does not lead to de-radicalizing the new barbarians and all the forms of despair that they themselves represent.

A true ‘de-radicalization’ can consist only in a new noetic dream. It is in this context that disruption requires a moral philosophy, as a way of struggling against transhumanism and for the Neganthropocene – via Bergson and The Two Sources of Morality and Religion.25 In the West, ὕβρις becomes the madness of logos in the ordeal of the ἴδιος κόσμος, and then the folly of the cross, and hence this ὕβρις requires a moral philosophy, and, more generally, those forms of knowledge of the moral (non-demoralized) being that are all the therapies and therapeutics of ὕβρις insofar as it always returns, and always returns via pharmaka – which alone, however, allow it to be contained.

The true object of Keynes’ critique is the unbinding and unleashing of the drives, which leads to moral disintegration, and which stems from the Anthropocene as disinhibition – an Anthropocene whose discourses on ‘ethics’, such as those described by Mark Hunyadi, are rationalizations that deny and repress. The morale of the moral being, however, is the most complex, most fragile and most necessary dimension of the doubly epokhal redoubling and the process of transindividuation – at the heart of which collective protentions are formed and deformed. But it is these collective protentions that, as moral ends and neganthropic strengths in being-for-life, and as being-for-noetic-life, are lacking in Florian.

The moral is what stems from αἰδώς and δίκη. Αἰδώς, as shame, will become the guilt that is opposed to divine justice, with monotheism’s interpretation of the facticity and artificiality of exosomatization as original sin. The Good will thus come to be opposed to Evil – which with bourgeois capitalism will result in bourgeois and petit-bourgeois morality, of which Emma Bovary’s demoralization and the ‘copyism’ of the ‘two imbeciles’26 are ordeals characteristic of what, in the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, thereby becoming Kakania, will install the neurosis that will then be discovered on the couch of Sigmund Freud.

Composed, the tendencies that extend the moral being as a dynamic temptation in bipolarity, of which the feelings for αἰδώς and δίκη are the primordial forms of knowledge, require the existence of a nomos without which there can be no Sittlichkeit: the morale of the moral being cannot do without the law. Disruption, however, sets the real outside the law [loi], and does so by realizing the real beyond any right [droit] – through the creation of legal vacuums, which amount, so we are claiming here, to a de-realization of reality that leads to entropic decomposition.

It is this abyss, which disruption hollows out between αἰδώς and δίκη, that radicalizes contemporary barbarism as totally accomplished nihilism. Along, then, with all the caring professions – along with all the carers, from doctors to teachers and via artists, curators and all those who officiate as well as politicians of a kind yet to come – psychiatry must open up a new question of law and of its relationship to the pharmakon. In France, this will undoubtedly involve the initiation of a dialogue with Pierre Legendre and Alain Supiot.

There are close links between the drives, lies and the madness of suicidal acts, some of which are also homicidal: these forms of acting out [passages à l’acte] are inseparable from the diseconomy and lawlessness afflicting psychic life and collective life, inasmuch as these are themselves dis-integrated by the capitalist diseconomy of disinhibition.

In ‘À la recherche d’une autre histoire de la folie’, Marcel Gauchet, along with Gladys Swain, offers a critique of Foucault and of everything that accompanied the transformation of the psychiatric institution in the second half of the twentieth century.27 But in so doing, and by restricting himself to medical questions, Gauchet misses the primary meaning of the Foucauldian approach, which consisted in politicizing madness.

The issue of madness in noetic life is, in a general way, what ties ὕβρις to the pharmakon, not only in the form of Laroxyl or psychotropics in general,28 but as exosomatization in all its forms. In the twenty-first century, this question arises in a completely different way, because this century heralds a new era of exosomatization that calls for a new form of noesis – that is, a new form of ὕβρις, and hence a new form of care.

131. One step forward, two steps back: accelerationism and its denial

Heralded everywhere – as the ‘quantified self’, medicine 3.0, synthetic biology, bionics, nanotechnological ‘enhancement’, neurotechnology, the discourse on ‘singularity’,29 and so on – the new era of exosomatization gives rise to two types of denial:

- the first, quite classically, consists in simply ignoring what has become obvious, so as not to be held back by it;

- the second denounces, in what presents itself as a coming catastrophe, the inherent evil to which technics that has become autonomized technology would amount, and so refuses to understand that the condition of the future is technological.

To say that the condition of the future is technological in no way means that this condition is a solution: it means, on the contrary, that this condition is a problem (and not just a question), and that what is required is a ‘great politics’ of technology, which must become a ‘great health’, that is, a transvaluation.

It is in this context that we should read and compare, on the one hand, the encyclical by Pope Francis, Laudato Si’,30 which clearly amounts to a bifurcation in Christian dogma with respect to man’s place in Creation, and, on the other hand, the ‘accelerationist manifesto’ of Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams.31 I will not comment here on Laudato Si’: this is a project currently underway within Ars Industrialis. The present work, however, is a kind of preparation for a dialogue with the theses put forward in the encyclical, and a way of saluting the courage of Pope Francis – and, in a way, his parrhēsia.32

Faced with the ‘continued paralysis and ineffectual nature of much of what remains of the Left’,33 as well as of the ‘new social movements which emerged since the end of the Cold War [and which] have been similarly unable to devise a new political ideological vision’,34 Srnicek and Williams propose a consideration of the question of technology in Marx from the perspective of ‘increasing automation’ and the ‘coming apocalypses’ of ‘neoliberalism 2.0’.35

This ‘Manifesto’ is in the first place a discourse on speed today, which is also to say on disruption: ‘We experience only the increasing speed of a local horizon, a simple brain-dead onrush rather than an acceleration which is also navigational.’36 A true acceleration would take up Marx’s initial inspiration:

[Marx] was not a thinker who resisted modernity, but rather one who sought to analyse and intervene within it, understanding that for all its exploitation and corruption, capitalism remained the most advanced economic system to date. Its gains were not to be reversed, but accelerated beyond the constraints [of] the capitalist value form.37

But when they then refer to Lenin,38 Srnicek and Williams pass over the central question, which is the philosophical question of pharmacology, as well as those questions to which it leads, which are the economic, political, social and ecological questions that this pharmacology poses through the problems that it raises – and which all fall within general organology.

But in the exosomatic perspective put forward by Marx and Engels, a perspective that lies at the origin of all their work, the pharmacological question fails to emerge. In The German Ideology, which is the first formulation of the organological situation of noetic life, pharmacology is understood only in terms of class domination – which means that it is denied in terms of pharmacology.

Marxism, and then Marxism-Leninism, failed to problematize the pharmacology of proletarian productivism, and hence failed to see that it is not the negative power of the proletariat that effects a ‘revolutionary’ bifurcation, but, on the contrary, a quasi-causal process of de-proletarianization – that is, an exceeding of the dialectic by what then becomes a therapeutics composed of knowledge (of how to live, do and conceive).39

Srnicek and Williams are right to say that the ‘material platforms of production, finance, logistics, and consumption can and will be reprogrammed and reformatted towards post-capitalist ends’,40 even if it is less sure that this will not involve a new type of capitalism. (On this point, I am also not in full agreement with the analysis of Michel Bauwens:41 even if, eventually, capitalism will disappear, the transformation currently underway is unlikely to lead to a straightforward exit from capitalism any time soon. In the short term, the question and the problem are to ensure that we do not disappear along with capitalism.)

Srnicek and Williams are right to want to reprogram the material platforms of what has become the ‘data economy’ that is leading to full and generalized automation. This is also what the Institut de recherche et d’innovation is working towards through its projects in the service of a negentropic web.42 A redeployment of digital pharmacology in the service of long-term post-capitalist goals, and undoubtedly composing with capitalism in the short and medium term, requires new forms of knowledge capable of providing new prescriptions – of how to live, do and conceptualize.43

Such prescriptive capabilities, as new forms of knowledge and of sharing knowledge, have everything to do with ‘capabilities’ in the sense in which Amartya Sen uses this term. They make it possible to overcome the ‘tyranny of lifestyles’ – which promises to be even more tyrannical with the transhumanist marketing we can soon expect. Such prescriptive capabilities, which are obviously at stake in the commons in the sense of Elinor Ostrom44 and Benjamin Coriat,45 must collectively individuate the new culture that true digital culture46 will be, rather than the current ‘tyranny of digital lifestyles’.

This culture will be that of a new moral being who, de-proletarianized, that is, once again capable of noetic dreaming, will expect nothing from ‘technological solutionism’. The moral being of the digital culture to come will be a practitioner, not a consumer. Sharing with other practitioners common and singular capabilities of producing bifurcations, that is, pressing the time saved by entropic automation into the service of neganthropological dis-automatization, this moral being will cultivate new forms of knowledge founded on a contributory economy whose canonical value (value of values) will be negentropy47 – which is the specific feature of the commons economy.

From a completely different perspective, but by relating the political and economic questions they raise to those involving the place of dreaming, Srnicek and Williams emphasize that the accelerationist project ‘must […] include recovering the dreams which transfixed many from the middle of the nineteenth century until the dawn of the neoliberal era, of the quest of homo sapiens towards expansion beyond the limitations of the earth and our immediate bodily forms’.48 Here, again, the conquest of space is seen as a prospect for the development of humanity and

it is only a postcapitalist society, made possible by an accelerationist politics, which will ever be capable of delivering on the promissory note of the mid-twentieth century’s space programmes, to shift beyond a world of minimal technical upgrades towards all-encompassing change.49

This spatial politics would thus rehabilitate the ‘mastery’ abandoned by the discourse of ‘postmodernity’.

This return by the accelerationists to a discourse of mastery (which critical theory and the deconstruction of metaphysics saw as an impasse to be overcome – and I have argued throughout the preceding that this impasse amounts to the Anthropocene itself) is not without inspiration from the same concerns that lie behind transhumanist ‘storytelling’. Hence Srnicek and Williams declare that their perspective opens towards ‘a time of collective self-mastery, and the properly alien future that entails and enables. Towards a completion of the Enlightenment project of self-criticism and self-mastery, rather than its elimination.’50 So long as it fails to see or refer to the shadows borne by the Enlightenment, so long as it does not take up these shadows as a theme, this return to mastery is bound to repeat the denial of ὕβρις, and, with this disavowal, the accelerationist manifesto takes two steps backwards after its first forwards step.

The disavowal of ὕβρις is also the disavowal of desire: it is desire that is everywhere at stake in these questions – insofar as it is, par excellence, the process of noesis as accomplishment of neganthropic capability, from dreaming to sublimation51 and via idealization.

132. Psychotic capitalism

What is a noetic dream that is left unrealized, that doesn’t come true? What becomes of it? Its non-realization proves that it was not yet truly noetic (this is the whole meaning of phenomenology as the exteriorization of Spirit in Hegel). Hence the frequent result is that a dream turns into a nightmare. In disruption as the de-realization of dreams concretized through an ‘age of devices’ that turns into a nightmare, we live through a generalized denoetization where dreams are concretized without being realized.

Insufficiently noetic dreams de-realize themselves to the extent that they produce dis-individuating and trans-dividuating dead ends that exhaust and annihilate the potential for individuation – that is, they exhaust and annihilate powers of the future: promises. It is the apparatus and devices of this de-realization of dreams that form the infrastructure of accomplished nihilism. It could be developed only because no pharmacological analysis has enabled the formation of this apparatus to be counteracted by another politics of technology. The various forms of denial – methodically maintained by professionals – have prevented the emergence of such a politics, by preventing them from dreaming, that is, from thinking.

This disappointing state of affairs is today widely observable as a proliferation of negative expectations and protentions, whether by citizens or by financial markets, insurers and investors – a situation of which speculators always know how to take advantage. In this context, depression, which is both moral and economic, becomes ‘psychotic’, clinically insane, so to speak, and, increasingly often, it leads to acting out – including as this criminal economic act that is speculation about the worst. Having de-realized the real, capitalism itself becomes psychotic. It is no longer just that it has lost its spirit:52 it has lost its reason.

In Acting Out,53 I recounted that, having myself acted out, I made an experiment out of my new retentional and protentional modality that was incarceration by trying to understand how and why I had managed to stop loving the world (which also happened to Claude Lévi-Strauss54) to the point of risking my life and ultimately finding myself locked away from the world. In 2003, twenty-five years after my incarceration, I concluded Acting Out by stating that, between the moment in 1978 when I entered prison and the moment when I would write my little book, the world had become much worse than before: it was in the course of being befouled [immonde].

Today, it is clear that the situation is again vastly more serious than it was in 2003: the world has become foul [le monde est devenu immonde]. This worsening of the situation is the crossing of a limit – one of whose names is disruption. This crossing consists above all in the fact of denoetization insofar as it is not simply the domination of stupidity: denoetization involves the question of a madness that goes beyond the bounds of νόησις (noēsis) and in so doing de-realizes the real. This has been made possible by functional stupidity, that is, by generalized proletarianization, which leads to that stage of rupture within which we are trying to live, but this is a stage that goes beyond systemic stupidity: it goes beyond these bounds and to the very extremities of the Anthropocene.

In this extremity, ‘extremisms’ proliferate – and first of all the extreme mediocrity of multiple forms of impotence, powerlessness and incapability. The various forms of collective regression disavowed by Jacques Rancière – from the far right to so-called jihadism and via the lies, indiscretions and speculations of the restless souls who govern this Titanic that the ‘Earth Ark’55 has become – all this is directly produced by the process of denoetization.56 The result is an immense feeling of disorientation on the verge of turning into global panic.

How to renoetize? Is it possible? To pose these questions consists in affirming that it is possible, which means: it is still possible to be put into question, and therefore to noetize. But to pose these questions also consists in envisaging that it might no longer be possible – were it otherwise, we would not even have raised the question: it would only have ‘seemed’ to have been posed.

133. The conversion to come

The question that now imposes itself, the question that truly arises in the age of disruption, is the question that can envisage its own impossibility – which is still the question of ὕβρις, but ὕβρις brought to its final extremity. Only such a question, imposing itself as the putting into question of the very possibility of questioning, and capable of envisaging its own impossibility, only such a question could produce a bifurcation capable of realizing this putting into question as a question, and not as the end of all questioning.

Here I use the verb réaliser also in the sense it has in English: to realize. Hence to realize the putting in question also means to discover and confront the countless organological and pharmacological problems posed by the putting into question of the possibility of questioning provoked by the fact that exosomatization reaches this new stage. In this stage, the question is that of a neganthropology that would be capable of producing the impossible, namely, the Neganthropocene. To produce the impossible is to create a kind of miracle.

The Neganthropocene is a noetic dream that ‘in all likelihood’ has no chance of being realized. It is for this reason that it is a dream: a true dream is always what presents itself as something that cannot be realized. It is in this way that it is oneiric. On those occasions when it is realized, however, it is because it has become capable of becoming a desire – and a shared desire. This desire is that of what, in the ‘Letter on “Humanism”’, Heidegger called Möglichkeit.57

In the highly specific context of the ordinary madness provoked by the absence of epoch, the question of renoetization through the reconstitution of desire – for which reason is first of all motive, that is, motor, and, therefore, the protentional dynamic as a whole inasmuch as it is the source of all quasi-causality qua imagination founded in dreaming – this question of renoetization through the reconstruction of desire must be investigated with the involvement of the world of psychiatry and the various forms of therapy for mental, psychological, cognitive and sapiential suffering. And it must thus confront the state of emergency that is disruption.

To confront this state of emergency that is denoetization qua disruption, and in order to inscribe within it the possibility of an impossibility that for this reason we are calling a bifurcation – which can only be the desire for such a bifurcation – also presupposes, beyond the therapeutic scene properly speaking, an encounter and discussion with scientific disciplines, with carers in general and with those from the spiritual world – ranging from yoga to the Vatican and from the ‘faithful’ to theologians – as well as with citizens and with historial politicians yet to come.

In the entropic state of emergency that is the concrete reality of the Anthropocene, the struggle against denoetization must understand noesis first and foremost in terms of the neganthropological faculty that is the ‘function of reason’. This requires a redefinition of the concept of negentropy (or of negative entropy, or anti-entropy) with respect to exosomatization as a reality that is both organological and pharmacological.

Neganthropy is not just negentropy: exosomatization modifies the terms of the question in the sense that, between negentropy, as characteristic of the organogenesis of life, and exosomatic organogenesis, which would be an organogenesis that is no longer just that of life, a new conception of organogenetic bifurcation is required, which I am here calling neganthropology – and which I oppose to transhumanist ‘extropianism’.

Insofar as it concerns all forms of knowledge, the whole set of which constitutes capabilities in Sen’s sense, and because denoetization is first and foremost the proletarianization of knowledge in all its forms (of living, doing and conceiving) – this annihilation of knowledge being its devaluation, that is, the fulfilment of nihilism – renoetization necessarily involves a vast and highly improbable process of conversion.

What our century would contain of the ‘religious’ – most of the time in the form of fantasy rather than of vocation, a fantasy resulting from a fundamental frustration exploited by the ‘jihadist offer’ – ultimately stems from the necessity of a conversion. Here we should read the legend of Saint Julian, which, like many others, tells the story of the conversion of a dealer of death – hunter, then warrior, then monk.58

Saint Julian the Hospitaller,59 as well as the samurai discussed by Hidetaka Ishida,60 and the Roman legionaries,61 individually and collectively invented new arts of living: new forms of peace, through noetic transformations of the conflict to which ὕβρις always amounts, and where this ὕβρις lies within every noesis, being the source of the noetic phase-shifts that are transindividuated into eras and epochs as the reality of noesis (this is what Gladys Swain highlights in Hegel’s relation to madness62) and through processes of conversion.

Foucault’s final period is completely devoted to the question of techniques of the self, as conversions of forms of noetic life. Noesis is first and foremost a kind of conversion, and an apprenticeship in new forms of life, tekhnē tou biou, and these apprenticeships, these lessons, lie at the origin of all forms of knowledge: conversion, as the moment of transition from existence to consistence, is the very dynamic of the life of the mind and spirit in all its forms – whether religious or otherwise.

We ourselves, we who belong to the twenty-first century, we are not warriors like the samurai who invented Zen culture, or like the legionaries who developed the culture of otium in the Roman Empire, or like the gathering of the heads of Homeric Greece that develops into the peaceful ἀγορά of the πόλις as the site of λόγος: we are in the midst of a global economic war – in which an oligarchy of the lords of economic war sit on boards of directors, and the masses of producers and consumers are its troops.

We can save the world from disruptive and entropic collapse only by negotiating economic peace treaties founded on an economy of reconstruction in the service of a new noetic era – cultivating new knowledge both as life-knowledge [savoir-vivre], work-knowledge [savoir-faire] and conceptual and spiritual knowledge. It is not a question of knowing if we should or should not bifurcate: we are going to bifurcate, beyond a shadow of a doubt.

The only real question is to know if it is possible for such a bifurcation to occur as the conversion of our way of life, or whether we will simply undergo the shift announced in ‘Approaching a State Shift in Earth’s Biosphere’ – a question that no one dares to formulate, or knows how to formulate. The conversion to come is that from becoming [devenir] to future [avenir]. This is what conversion has always meant – and it is always involved in every truly noetic act, in every new occurrence of truth, which always occurs by echoing, whether near or far, a shaking-up [ébranlement] produced via ὕβρις – a shaking-up that the Bible calls original sin, which lies at the origin of knowledge [connaissance],63 and which I describe here as noetic exosomatization – of which προμήθεια (promētheia) and ἐπιμηθεια (epimētheia) are the two inseparable faces64 through which the pharmakon is constituted, and to which the default of origin has amounted since the very beginning.

134. The onrush into the computational

Derrida relativizes Foucault’s opposition between, on one side, Descartes, and, on the other side, Montaigne and Pascal. In so doing, he argues that madness constitutes the Cartesian cogito: not simply reason, but what in Descartes amounts to the very name of thought. The constitution of the cogito is God. It is God as infinity – as infinite power.

After the death of God, what possibility remains for madness to yet be, in thinking, that which would com-pose analysis and synthesis, infinitizing the end as its différance? Disruption is the dramatization of this question, which raises a thousand new organological and pharmacological problems. First among these problems is the status of this noetic organ that is Turing’s ‘universal machine’ as a noetic dream of noesis as exosomatization.

We can discover no formulation of these questions and these problems in the work of the philosophers of whom we are the heirs. They have just barely transmitted to us this question that they have not themselves been able to formulate: the philosophical legacy of the twentieth century has transmitted only conditional elements of questions that come to be formulated in the disruptive context of the twenty-first century, questions that these earlier forms of thought were unaware of, and that they failed to see coming.

The ‘conditional elements’ furnished by twentieth-century philosophy, oftentimes alongside psychoanalytic and psychiatric therapy, must be taken into account, not by rehashing them, but by interpreting them.

The infinite resurfaces in the metaphysics of our time with computationalist cognitivism: it presents itself discreetly, as the infinite tape of the Turing machine65 – which is infinite in the way that the memory of God is infinite in Leibniz. This is what cognitivism continually denies. In those ‘Turing machines’ that are computers, of course, the tape is not infinite. The tape is infinite only in principle [en droit], that is, mathematically: in the noetic dream, but not in its realization.

The passage from the dream to its realization is, from the beginning of the Anthropocene, the transition from science to technology. The tape is infinite only ideally. The industrial concretization of Turing’s noetic dream – as the retentional basis of calculation in totally computational capitalism – is its finitization. Turing, whose computationalist metaphysics will be utilized in both the 1936 article on computing machines66 and the 1950 article on the intelligence test,67 will himself put in question this neutralization of the finitude of the memory support by turning to biology, as Jean Lassègue has shown.68

In Automatic Society, Volume 1, I endeavoured to show that the finitization of Turing’s noetic dream by computationalist metaphysics is reflected in the implementation of an algorithmics that exosomatizes the analytical functions of the understanding by separating them from the synthetic function of reason. Algorithmic exosomatization then necessarily becomes a pharmacological problem: one which consists in prescribing a fecund – that is, truly noetic – arrangement between the finite memories of the new exosomatized computational organ and the neganthropic cerebral organs, via social organizations. As a pharmakon, however, this artificial organ makes it possible to short-circuit these social organizations, setting up the tragedy of disruption proclaimed by Chris Anderson’s ‘end of theory’.69 But this would then amount only to the first stage of a doubly epokhal redoubling, which could and should lead to a second stage: not just to a new epoch, but to a new era, which we are dreaming of here as the Neganthropocene.

The pharmacological problem posed by the algorithmic organology in which the exosomatized understanding consists – which is also and firstly a political, economic and ecological problem – is what computationalist and libertarian metaphysics denies. This denial constitutes the framework of the theoretical legitimation of the current madness of capital. Herbert A. Simon, both an economist and a computationalist cognitivist, is a perfect example of this link between cognitivism and a capitalist economy that has lost its reason.

The madness of capitalist and cognitivist computationalism consists in believing and in making others believe that the computing machine could be infinitized, which is impossible otherwise than in principle [en droit], which is to say that it is impossible other than for an abstract machine. If we also want to infinitize it in fact, that is, concretely, then this can lead only to what Hegel called bad infinity – as a factual impossibility of finishing, for example of finishing the series of integers, and, therefore, as the impossibility of bifurcating – which is also to say of deciding, which leads to a headlong onrush into the computational.

We are living through the finitization of the infinite, that is, the attenuation of desire: such is contemporary ὕβρις. Capitalism has finitized the infinity of Christ’s power by realizing it on earth. In so doing, the dream of Christ has turned into a nightmare – in being concretized through calculation, and as the de-realization of this dream. Descartes will be finitized in the same way, through the rationalization by which the Aufklärung will enter into decline, constituting disciplinary techniques and then psychotechnics in place and instead of any autonomy, and engendering a ‘new form of barbarism’.

Founded as they are on the calculability of the audience market, and on an economy of attention that destroys this very attention, the culture industries are now being replaced in the age of disruption by the ‘data economy’, which can only intensify barbarism qua finitization of this infinite – on the basis of Noam Chomsky’s neurocentric gesture, replacing Cartesian ideas with neuronal ‘wiring’, thus erasing the question of idiomaticity that fundamentally arises from exosomatization as ex-pression, and liquidating the Saussurian dynamic of diachronic and synchronic tendencies as that through which idioms are metastabilized.

135. Creating a miracle: despair, salvation, fidelity

Lost in disruption, wondering how it is possible to avoid going mad, proclaiming that noesis is, nevertheless, the quasi-cause of madness, that is, of ὕβρις, like Simon, Nicolas and Camille at the beginning of the final scene of Same Old Song, I hereby confess that I am very depressed, and that I am sometimes overwhelmed, literally laid low, by what seems to me to be, as perhaps it does to Florian, evidence of the end.

I am often overwhelmed because it seems to be absolutely irrational to believe that a positive bifurcation could arise from out of the chaotic period into which we are rushing at the high speeds imposed by disruption. It is totally improbable. And this is a motive for despair.

In the ordeal of absolute despair that results from such considerations, one conclusion seems unavoidable: only a miracle could overcome the absence of epoch into which nihilism has led us. Heidegger put it another way: in a 1966 interview he gave to Der Spiegel, he declared that ‘only a god can still save us’.70 Having incited irony, including mine, and sometimes hatred, today this statement resonates in my own ears with renewed vigour. What I believe, however, is that the question is less that of a god than of a miracle. This is my belief because I also believe that the miracle, on the one hand, and dust, on the other hand, are the expression of the way that monotheistic thought prior to thermodynamics was able to conceive what is not conceivable – that which lies at the origin of life. This origin was long thought on the basis of what we have for a long time called God, but, since the twentieth century, it has been thought on the basis of what has been referred to variously as negative entropy, negentropy or anti-entropy.

To continue to struggle, faced with the evidence of the absolutely desperate nature of the situation – that is, to stop denying the state of emergency into which the Anthropocene has led us, taken to the extreme by disruption – it is necessary to believe in the possibility of a miracle, and, more precisely, to believe in the miracle of what I am here calling the Neganthropocene.

Let us repeat it once again: such a miracle is a dream. This dream must be immensely noetic, capable of projecting the pharmacological situation in advance by turning it into its point of departure – by positing the irreducibility of this pharmacological situation from the outset, which is to say the impossibility of eliminating entropic consequences, and, correspondingly, the constant need to neganthropologically take care of the pharmakon.

In the past, the name given to unconditional belief in the possibility of the miraculous was faith, itself founded on the form of desire that Christianity called ἀγάπη (agapē). In the epoch of the absence of epoch to which the death of God has led, such an affirmation of the possibility of what can only appear impossible, which is the improbable as such, that is, neganthropy with respect to entropic becoming, can no longer constitute a faith in Providence, nor can it be the expectation of a divinity. This, however, raises questions about a new form of belief and a new relationship to fidelity and infidelity.71

It is in this sense that we should, not reject Heidegger’s statement in Der Spiegel, but subject it to critique, that is, take it seriously,72 analyse it in terms of its fundamental inadequacies – in this case, the exclusion of questions of entropy and negentropy from Heideggerian thinking. Here, it is no longer a question of the ontological difference between being and beings, but of the neganthropic (and exosomatic) différance between future [avenir] and becoming [devenir].

It is not a new god who alone could still save us (even temporarily, through a différance of and within entropy that can but remain the fate of the cosmos – this fate being, in local terms, the cooling of the solar system73), but the new belief required for the transvaluation of all values, which presupposes that we ‘transvalue’ Nietzsche himself.

Miraculous narratives are parables of the neganthropic condition inasmuch as it is always exceeding itself, and such that it can never amount to a simple ‘humanism’. Because it is hybrid, and because the ὕβρις it contains always exceeds it, what we call ‘man’ – the non-inhuman being that we should henceforth name Neganthropos – is both in excess and in default of itself: it is never itself.

It is this excess, inasmuch as it ‘transcends’ the default that it is, that takes the name of spirits, gods, God, History or Gestell, and this is what jihadism as well as transhumanism and neo-barbarism try to recuperate at the moment when this excess shows itself to also be the default as default of origin.

Excess and default are what Heideggerian existentialism, in spite of all that it brings to such a perspective, is ultimately incapable of conceiving. This is the objection to Heidegger that Derridian deconstruction is attempting to make. The consequence of this inability is that the place (Ort) of the ontological difference (that is, of ‘meditative thinking’) becomes the ‘native land’, ‘autochthony’.74 The excess and the default from which neganthropological différance stems, however, are at the same time what localizes the default as idiomatic difference and what de-localizes (exceeds) it as what is necessary beyond the locality where it is constituted, drawing it out towards the non-place of what, in becoming, remains to come, and as the quasi-causal taking place of a promise. For centuries, this excess was experienced as that transcendence whose name was God.

Heidegger could not manage to think this. And yet these are the stakes involved in what he terms Ereignis. Derridian deconstruction is itself insufficient to overcome the way in which Heidegger fails to think ὕβρις (as excess and as default, as having a hybrid and ‘factical’ character), because it fundamentally downplays noetic différance, and hence downplays the fact of exosomatic organogenesis as the condition of its own possibility (and its own impossibility).

This retreat of deconstruction faced with its own consequences equally amounts to an inability to think the fact of proletarianization – which means that it is also an inability to think capital, and ultimately the supplementary history of calculation, as well as calculation as the impossible fate of the supplement that must be, not just ‘sublated’ [sursumé] or ‘raised’ [relevé], but therapeutically neganthropized, which also means, transvalued.

136. Denial and the obsolescence of man, according to Günther Anders

It is the question of a modest miracle that lies on the horizon of the words of René Char previously quoted75 – and this horizon forms the question of locality: ‘Today we are closer to the catastrophe than to the alarm, and this is why it is high time we composed a health of misfortune. Even though it may have the arrogant appearance of a miracle.’76 To the hypothesis of just such a miracle without transcendence, without arrogance (despite its appearance), in some way an ordinary miracle – which would pass through the ‘health of misfortune’, which can only be a worthy form of courage, and of the courage of truth, which is also to say of parrhēsia, and, like Canguilhem and Vernant, Char too had the courage to fight – to this hypothesis, Günther Anders might object with what he presented as a ‘Molussian dictum’: ‘Courage? A lack of imagination.’77

If I understand it correctly, this statement suggests that courage would be a form of illusion and denial. And I believe that Anders, like Heidegger, whom he claims to be opposing here, on the one hand ignores the pharmacological question resulting from exosomatization, and on the other hand does not investigate the neganthropic possibility that lies within anthropy, because he says nothing about the questions opened up by the theories of entropy and negentropy.

Nevertheless, Anders is in all likelihood the first to have unwaveringly questioned the situation in which we find ourselves today, by reflecting on the consequences of the atomic age, which he himself understood as the age of the bomb – from an angle completely different from that of Heidegger. To live ‘under the sign of the bomb’ is to find oneself thrown back onto a terra incognita. And on this ‘unknown terrain’, this is firstly to deny the unknown, that is, the meaning of the bomb as a new ‘invisible’ object:

While it should be constantly present in the glare of its threat and its fascination, it remains […] hidden at the very heart of our negligence. The great affair of our age is to act as if we do not see it, as if we do not hear it, to continue living as if it did not exist.78

It is systematically kept incognito […] the ears into which one tries to speak become deaf as soon as this subject is mentioned.79

At stake with the bomb is the obsolescence of man. For with the bomb, and more generally with the ‘second industrial revolution’ and its scientific technology, human beings have become the ‘lords of Apocalypse’ and are ‘themselves the Infinite’ qua infinite power of destruction: ‘If there is something in the consciousness of humanity today that is absolute or infinite, it is no longer the power of God […]. It is our own power […]: the power to annihilate, to reduce to nothing.’80 Anders shows that this infinite power exhausts desire – which was still that of Faust – and brings forth new ‘Titans’.81

All the questions raised by Anders, which in the essay ‘On Promethean Shame’ anticipate transhumanist ideology, arise again and proliferate in our absence of epoch – where the bomb remains a major threat, but where the question of new Titans is infinitely more specific and complex, and where denial is vastly increasing, as Anders himself noted more than twenty years after The Obsolescence of Man was first published: ‘Now atomic power stations obstruct our view of nuclear war and have made our “apocalypse-blindness” more blind than ever before.’82 As for the bomb, it poses for Anders the question of a decision – which, through a process of transindividuation, should eventually lead to a collective renunciation.

I believe, however, that Anders, like Heidegger, fails to ask the overriding question. Anders insists that

the desire to revolt against the machines, to reject this Titanic condition we have acquired (or that we have had imposed upon us), [is] a highly dubious, extremely dangerous desire, for […] it […] strengthens the position of those who effectively hold total power in their hands.83

After insisting on this fact, after emphasizing that it is futile to oppose Titanic becoming and the infinitization of Promethean power, he nevertheless has nothing else to propose except such opposition – and in this way his reasoning seems highly contradictory.

This is so because, like Heidegger, Anders ignores the issues of entropy and negentropy, and exosomatization and its consequences, which are here characterized as neganthropological, organological and pharmacological. He begins his analysis of the atomic situation by condemning Heidegger’s discourse on this score, but he does not succeed in fundamentally distinguishing himself from Heidegger’s position.

137. Conversion as the taking place of locality

The atomic question, inasmuch as it stems from a technology that seems to replicate, on the local scale, the cosmic process in its totality as local thermodynamic combustions and transformations, requires that we situate noesis in the cosmos and as locality within the cosmos.

In noetic locality, a neganthropic différance is produced through exosomatization, which locally defers not just the law of entropy, but also the law of anthropy, namely, the toxicity of the pharmacological condition, so that locality is organized and ordered within universal becoming but against the current.

This cosmic dimension was taken on in 1936 by Eugène Minkowski, who, in the wake of Binswanger, inscribed it within the psyche. After having placed attention at the heart of his reflections, Minkowski emphasized that ‘we are accustomed to considering attention as an individual faculty, varying from individual to individual […]. Attention, however, can be envisaged from a completely different angle.’84 Attention is ‘one of the salient features of the general fabric [contexture] of life’,85 whereby

phenomena connected with the self surpass it […] towards the concrete environment [ambiance], but, at the same time, do so in the form of a vast arc that can encompass both the self and this environment, revealing to us, above and beyond it, the general fabric of the cosmos.86

And, in this context, it is striking to read Montaigne’s description of Socrates’ ‘fuller and wider’ imagination as one that ‘embraced the universe as his city’.87

Hence Minkowski raised the question of a locality within the universe, which was no doubt already at stake in the Aristotelian thought concerning place, which we find evoked by Italo Calvino at the end of his Invisible Cities, as the question of admiration and the admirable, which is also to say of the miracle (in the sense that Char, too, tries to let us hear):

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.88

To make room [faire place] is to give a place (for) [donner lieu].89 To take place [avoir lieu] is always, for a noetic soul, what gives a place for meaning [sens] (for significance90) that arrives with the non-sense (in the insignificance) that exosomatization is perpetually also producing – a nonsense that, when it approaches the insane or the senseless [insensé], is called the Devil. The question of sense is tied to that of the taking place that gives a place for, which has room for, which is a place, a site, Ort.

But the question of place, of taking place, that is, of what, as event, happens, arrives, and, more generally, the question of locality in a sense that is not just that of meaning [sens], and that has to do with space, spatialization, and hence in some way with exosomatization, which is also to say with geography, with geology, with urbanity, with territoriality – this question has today been totally transformed by the relationship between entropy and negentropy.

All negentropy is local, and comes at the cost of an increase in the rate of entropy outside this locality. Hence arises the question of an economy of localities, and of what constitutes localities as their organology – which in this case always involves territorialized processes of exosomatization, that is, of the production of tertiary retentions, which always generate processes of deterritorialization due to the detachability of these organs, which are also objects of exchange, including as verbal organs, and which in this sense constitute an economy. It is precisely at this point that we must read Georgescu-Roegen.

In the Anthropocene, that is, in the epoch of the absence of epoch to which the death of God has led, the affirmation of the possibility of what is bound to seem impossible – and which is the improbable as such, that is, negentropy as such, but which we must think and specify beyond negentropy and as neganthropy – can no longer amount to faith in Providence, nor therefore in divinity. Miraculous narratives are parables of the neganthropological condition inasmuch as it always exceeds itself, and which for this reason can never amount to a simple ‘humanism’.

How could such a conversion be produced from out of the absence of epoch? By creating worlds in the befouled unworld [immonde], by again giving room (for), by proliferating acts of taking place in a thousand places making (the) différance. This is what we are told by René Char and Italo Calvino, giving birth in sites of urbanity to miraculous relations of mutual admiration where the hell or the inferno recedes before what, ‘in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space’. This place, which is also a χώρα (khōra), is the place of neganthropological différance – whose advent in Gestell must occur as a leap into a new era.

138. Dragons and serpents

In the cell where I accumulated tertiary retentions, which were of diverse forms but all literal (there were no images, no objects, nothing but letters), between which I created links (which I annotated), I caused a world to emerge from within the carceral desert that is an absence of world. This proceeded through the spatial exteriorization of the temporal fluxes and flows of my primary, secondary and tertiary retentions, from which protentions arose that even today constitute the motives by which and for which I strive to let my concepts take shape [faire corps].

The therapeutic power of this meletē was due to the spatialization of my time through the tertiarization of my reading, then the reading of my writings, that is, of my previous tertiarizations. This spatialization opened up my analytical access – critical, discerning, discriminating, mobilizing the conceptual powers of the understanding – to the synthesis in which my readings and writings in general consisted.

Hence I acquired a very practical notion of différance as thought by Derrida, and highly ‘différant’, if I may say so, from that of the orthodox ‘Derridians’. Similarly, I understand Heidegger’s ontological difference very differently than do the Heideggerians – including Granel.

From this différance, I had an irreducibly idiomatic experience in the sense that, reading a great deal of Mallarmé, I projected into the linguistic idiom an irreducible mark of locality. This is the condition of all singularity, which is also to say of any significance of the non-insignificant (the insignificant being itself the condition of the idiom and of the ἴδιος in general).

The trials and ordeals of my différance led me to indeed posit that readers, that is, psychic individuals ex-pressing the significance of the non-insignificant in the process of noesis, can signi-fy (make signs) only because they already harbour within themselves the synchronic and diachronic tendencies that condition all transindividuation – in the form of rules that constitute their idiolect, and that are inherently local.

This is why, during these years, I questioned what I called local-ity, that is, the irreducible belonging of any noetic différance to a place, to a giving place (for), including and even always on the basis of a non-place – the default of origin, delinquere. What was happening to me amounted to the formation of what I decided to call an idiotext, itself always included within other idiotexts, an innumerable, indefinable number of other idiotexts. I maintained that what happened to me in this way was an accidental localization of an irreducible local-ity of which noetic différance was the processual and idiomatic test, trial and ordeal.

I tested out the irreducible character of the idiomaticity of all noesis, and the fact that an idiom is what, giving place (for), is caught in and by what, by this very fact, takes place. Exosomatization is both what gives place (for) and what wrests away from place: it is the non-place (the default) wherein everything happens somewhere, that is, partially, and, provided that a mutual admiration can thereby emerge, as that which is necessary. I decided to call this emergence ‘virtue’ – as that which can turn necessity into virtue.

Given that exosomatic organogenesis is organological and not organic, the artificial organs this forms are producers of entropy as well as negentropy inasmuch as they provoke an epokhality that always begins and ends in a fundamental disorder – that of the hubris starting from which noesis transindividuates new epochs and new eras. Eras and their epochs are the temporal and spatial processes of différance over the course of which the arrow of time, insofar as it amounts to both an anthropic dissemination and a neganthropic economy, becomes that historical irreversibility founded on the infidelity of milieus, and, through them, of places.

Over recent years, and in the framework of the seminars and summer academies of pharmakon.fr, I began to re-elaborate this theorematic body on the basis of neganthropological différance, in particular when I attempted to interpret, through a reading of Maurice Godelier’s The Metamorphoses of Kinship,91 Lévi-Strauss’ ‘entropology’ and the consequences stemming from anthropology’s rejection of Leroi-Gourhan.

Here, confronted with the challenge of the conversion required by the advent of a new era, and, as was the case during my imprisonment, in order to struggle against the madness it can provoke, and by turning this possibility of madness into the source and resource of noesis, I came to revisit the story that began in a cell in Building A of Saint-Michel Prison, and that ended in a cell of Building F of the Muret detention centre. I had to leave the latter in February 1983: this was the moment when I had to convert once again back to the normal life of men and women free to come and go in what had become befouled and worldless [immonde].

For more than fifteen years, I wrote a good portion of my books by recording into a dictaphone the thoughts that came to me as I drove on Mondays and Tuesdays along the northward-bound motorway on the way to seeing my students at the Université de Compiègne. Then I began to make recordings while cycling in the beautiful hills of the Bourbonnais, in the south of the department of Cher, on the border with Allier, close to the Creuse river. This desert locality has always made me dream, and sometimes made me delirious.

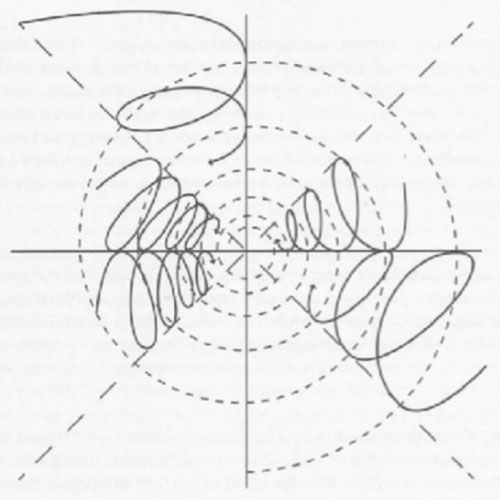

It was there that with my wife Caroline I created the pharmakon.fr course dedicated to Plato, then the summer academy held each August at the Épineuil mill. When I first began to use a digital dictaphone, Caroline would transcribe the audio files by typing them up using a keyboard. Then she began to use Dragon, a software that enables semi-automatic transcription. In writing these confessions that took me back to my time at Saint-Michel prison, I was suddenly struck by the name of this software, in which I had never heard anything except a brand name.92

Saint Michael fights the dragon, who is a figure of the diabolical, dialogical, demonic and diachronic serpent that, as Philippe-Alain Michaud93 has pointed out, also symbolizes lightning for the Hopi Indians of Mexico and for Aby Warburg who visited them – of which Warburg rendered an account in his celebrated ‘Lecture on Serpent Ritual’,94 delivered, after he lost his reason, at the Bellevue Clinic in Zurich, at the invitation of Ludwig Binswanger, who was director of that psychiatric facility.

The dragon is a serpent – like the Aztec feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, and like all the monsters that haunt mythology all around the world, and therefore also in Greece and Judea. The serpent who tempts Eve is, in duplicating the mark of Asclepius and Hermes, a therapist and hermeneuticist of the pharmakon. The serpent that haunted Warburg lay behind so many of the revenances of which his Atlas was composed – from the Laocoön to the rattlesnake whose head the Mexican Indians placed in their mouths.

The serpent symbolizes lightning – the bolt of lightning – and hence electricity, and therefore divine, celestial, Olympian fire, which in human hands becomes the pharmakon. In disruption, thinking would be perpetually outstripped and overtaken precisely because optoelectronic digital tertiary retention can move twice as fast as lightning. Overtaken by what has become quicker than the fire of Zeus, noesis would arrive always too late, much too late, and would find its dreams turned immediately into nightmares. Such would be denoetization in the befouled unworld of the absence of epoch.

How can we ensure the possibility of questioning – of becoming the quasi-cause of what thus puts us into question – which is the possibility by which the noetic dream begins? How to ensure that noetic dreaming is not outstripped and overtaken? How can it be renoetized in order that it could become the quasi-cause of denoetization itself? It is possible only on the condition that noesis can move faster than the algorithms that are themselves twice as fast as Zeus, a fact that equates, not just to the death of God, but to the death of the gods of Olympus, and, along with them, of Heidegger’s god who alone could still ‘save us’.

To go faster than what goes twice as fast as lightning is, however, possible – and it is not just possible: it is the only possibility, if the possible is what is fundamentally different from the probable, and as the Möglichkeit through which a desire is realized. This possibility is precisely that of the bifurcation, which moves infinitely faster than every trajectory pursued in becoming, since, as its quasi-cause, it reverses this becoming within which it opens up the sole motive for hope: the future as improbable possibility.95

What then is desire? This is the question posed to us by Charles Perrault’s ‘The Fairies’. It is serpents, snakes that fall from the mouth of the wicked sister, a shameless liar – and, ‘for good measure’, they are mixed with toads: desire is not envy, or covetousness, or ambition, which are only the deadening decomposition of what, in desire, affirms itself as being-for-life. Desire is already courage, which is admirable only because it admires – which makes it courageous, just as Pascal is disturbing because he is disturbed.

‘Why is Pascal disturbing? Because he is dis…dis…’ ‘Turbed’, put in M. de Charlus.96

As I finish this book, I find myself reading Pierre Jacquemain’s column in Le Monde, after his resignation from Myriam El Khomri’s Ministry of Labour over their disagreement concerning the law on the right to work. We must read this courageous text, not just because it is exemplary, and exemplary precisely in the fact that it is courageous, but also because it speaks of nothing other than what forms the flesh and blood of this book:

In order to do politics, we must dream.97